Oral-History:Robert Saunders

About Robert Saunders

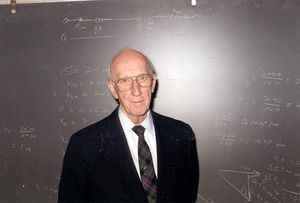

Robert Saunders completed his undergraduate education at Hamline University in St. Paul, Minnesota and his graduate work in power engineering at the University of Minnesota. In 1944, he was commissioned into the Navy and assigned to work on Special Project 157 (the Manhattan Project, at Oak Ridge, TN. After a year on the Manhattan Project, he was transferred to Italy. On his return to the United States, he became professor of electrical engineering at the University of California, Berkeley, where he was chair of the department from 1959 to 1963. In 1965, he moved to UC Irvine, becoming the dean of the college of engineering. In the late sixties he became heavily involved with the Educational Activities Board of the IEEE and in 1972 wrote a ten year plan for the EAB. In 1975, he became vice president for regional activities and in 1977 he was elected president of the IEEE. During his tenure as president, he headed an historic trip to the People's Republic of China. Saunders died in March 2009.

The interview begins with a brief overview of his education and early experiences in the Navy. Saunders then turns to his work with the IEEE. He explores the changing roles of IEEE committees over time, and focuses on such key moments as the adoption of a code of ethics by the IEEE. He discusses the ways in which the board of directors functions and looks at changes in the office of the president, specifically in the addition of the position of president-elect. He also explains how presidential elections occur, and the types of politicking that lurk behind them. He describes his role as president, the tasks he undertook domestically, and his trip to China in 1977.

About the Interview

ROBERT SAUNDERS: An Interview Conducted by Frederik Nebeker, Center for the History of Electrical Engineering, 21 February 1995

Interview #238 for the Center for the History of Electrical Engineering, The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc.

Copyright Statement

This manuscript is being made available for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the IEEE History Center. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of IEEE History Center.

Request for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the IEEE History Center Oral History Program, IEEE History Center, 445 Hoes Lane, Piscataway, NJ 08854 USA or ieee-history@ieee.org. It should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user.

It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows:

Robert Saunders, an oral history conducted in 1995 by Fredrik Nebeker, IEEE History Center, Piscataway, NJ, USA.

Interview

INTERVIEW: Robert Saunders

INTERVIEWER: Frederik Nebeker

DATE: 21 February 1995

LOCATION: Irvine, California

Career overview; AIEE membership

Nebeker:

This is the twenty-first of February 1995. I'm talking with Robert Saunders at his offices at U.C. Irvine. This is Rik Nebeker. Well perhaps then we'll start with your connection to IEEE, or its predecessor societies. I think you told me that you became a student member.

Saunders:

Yes, I became a student member at the University of Minnesota when I joined. I came from a small college in Saint Paul. I became a student member the first year I was at Minnesota.

Nebeker:

In 1936?

Saunders:

In 1936.

Nebeker:

That was AIEE.

Saunders:

That was AIEE, that's right.

Nebeker:

You were interested in power engineering?

Saunders:

Yes, at that time. Communication engineering was a relatively new field at that time; it was mostly telephone engineering, or radio. Radio was in a pretty primitive stage.

Nebeker:

What did you do when you finished your degree there?

Saunders:

I went to work for an electric machinery company as a designing engineer. I spent five years with them, part time. I never worked more than half time on the average, and during the summer I would generally work more than half time. But the university had a naval training school, functioning after Pearl Harbor. In fact two weeks after Pearl Harbor, the president of the university was importuned by the Navy to provide facilities for a naval training school for electricians’ mates. We turned out four thousand from there. I was the number three person in the school’s administrative structure. And I was also a teaching assistant, and taught classes, both lecture and laboratory classes during that same period of time. Then in 1944 I was commissioned and spent two years in the Navy.

Nebeker:

What was your job with the Navy?

Saunders:

I was sent to Special Project 157, which was the Manhattan Project, in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. The principal purpose of having military personnel there, Navy personnel in particular, was that an engineer in the navy was classified as mechanical, electrical, as civil, whereas in the Army engineers were all civil engineers. So they needed people who understood the military aspects of engineering. Why military? Because the security system required that people who worked on the Alpha project were not permitted in the Beta building and other buildings. They used military personnel because we were under [rocks and shoals?], which told us what would happen if we compromised the country, not that any one of us would do so, but they wanted us to know that they had their finger on us. So I was there for a year, and then I spent a year in ship repair in Morocco, and in Palermo, Sicily. Then I finally mustered out when they were scraping the bottom of the barrel--I was sent up to Naples, and made assistant chief of police of Naples.

Nebeker:

Military police?

Saunders:

Yes, military police. The Army was in charge; the chief of police was an army officer. I had some rather interesting experiences in the military police, because I had to meet every ship that came in and tell them what was off limits. I had to go out and pull sailors off the street and carry them back to their ships. My crew and I did this. This only lasted I think about four months.

Nebeker:

What did you do when you left the Navy?

Saunders:

I came back and joined the faculty at the University of California at Berkeley. I was there until 1964, then I had a joint appointment there and here in 1964, and then in 1965 I became dean of engineering here. I organized the engineering program.

Nebeker:

I see. And you continued to be an AIEE member?

Saunders:

Yes, I was an AIEE member, and I wrote my first paper I think for AIEE, back around 1948 or 1949, on permanent magnet generators. I continued to produce about a paper a year.

AIEE theory group; group and society memberships

Saunders:

In the AIEE hierarchy I worked closely with the electric machinery groups, because of my background in design. I was the founder of the Theory Committee, of what is now the Power Engineering Society. I visited them here a couple of years ago when I presented a paper in 1991, and found that they were still functioning, and still sponsoring theoretical papers.

Nebeker:

What was that called under AIEE? Was it a group?

Saunders:

No, I can't remember now, it may have been a committee. It was probably a committee. I don't remember the exact organizational structure.

Nebeker:

It was probably a committee under AIEE.

Saunders:

I served as a chaperone when the AIEE was working on standards. I would be invited to dinner so that General Electric, Westinghouse, Reliance, all those companies wouldn't be accused of anti-trust infringements. I was the chaperone.

Nebeker:

Did this theory group that you organized continue?

Saunders:

Oh yes. It's still in existence. As I say, I met with them in 1991.

Nebeker:

Oh, that particular theory group, I see.

Saunders:

Yes, the same group. Well, it wasn't the same people, but -

Nebeker:

Within the Power Engineering Society.

Saunders:

But it was in the Power Engineering Society.

Nebeker:I see.

Saunders:

I consider that to be my major society, although I'm a member of the IAS, and the Magnetic Society, and the Education Society, and the Control Society - I guess I'm no longer a member of the Control Society.

Power engineering

Nebeker:

What areas did you work in yourself, besides power?

Saunders:

Well, I pioneered the use of computers for design purposes.

Nebeker:

In power engineering?

Saunders:

In power engineering. I did most of this work, mostly at Berkeley. As a result a lot of the consulting work I did for various people usually had to do with analysis and design. I tried to make use of the computers, such as they were in those days. I encouraged a student of mine who was on the faculty to write a paper, or write a dissertation on design. Design is made up of two kinds of variables, discrete and continuous, and the mixture of those two poses certain problems when you try to apply system theory to it. He wrote an algorithm, and we worked together very closely on it. He turned out three papers on it, and one of them was jointly written with me.

Nebeker:

And that was an influential paper?

Saunders:

It was widely cited in the journals.

Nebeker:

Who was this student?

Saunders:

Roland Shinzinger. A good Swiss name, but he's German.

Accreditation committee; Educational Activities Board

Saunders:

Well, to continue, I stayed active in the Power Engineering Society, not as much as I was in the '50s, because I became involved in accreditation in the '60s. I was department chairman at Berkeley, which is a full-time job, but I still kept my hand in teaching. So I withdrew to some extent from activities in the societies, but then I was appointed to the accreditation committee of the ECPD. Jim Mulligan was the chair of that committee. The year after I joined the committee, I was appointed an IEEE representative to the committee. I continued with them for a total of six years. The way the structure was set up at that time was: you were chairman, and then you were past chairman for one year, which added up to six years. So I was chairman of the committee in 1969 and 1970. I had to work with EAB to some extent -

Nebeker:

That's the Educational Activities Board?

Saunders:

The Educational Activities Board, and the chairman, and with the board itself. Then, when the chairman of the board took a sabbatical to go to Spain, I was appointed acting chairman for the interim- without a membership on the board of directors. But the year following that, I was elected to the board of directors, as the chairman of the educational activities board. At that time the chairman of the Educational Activities Board was not a vice presidency and putting that was one of the things I accomplished as a member of the board. I felt that the education community should be represented, on the board because the preamble of the constitution of the IEEE states, that education is one of the founding structures of the IEEE.

Nebeker:

So how many vice presidents were there?

Saunders:

Well there was publications, regional activities, technical activities.... I guess those were the vice presidents. I was the executive vice president. The other member of the board who was not a member of the executive committee was the standards chairman, at that time, as I recall.

Nebeker:

So this was a change of the constitutional by-laws to make the chairman of the -

Saunders:

Yes. I'm not sure it was a change of the constitution, but it was a change of the by-laws. I also was instrumental in getting the institute to abolish the position of past -senior past-president, and put in the president elect. When I went to meetings of the other societies, ASME, the SE, etc., I found that I was the only sitting president when I went. They all had president-elects going to the interdisciplinary meetings. I wondered why the IEEE did not conform with the rest. I felt it quite keenly that this was one way for the incoming president to know what's going on in the other societies. I thought it was quite valuable for me.

Nebeker:

Is that something that the president-elect has taken responsibility for?

Saunders:

I don't know whether he did or not. There was generally a meeting once a year or twice a year of the founding presidents, ostensibly to argue with the landlord of the building on 48th Street, that landlord was on the engineering council, or something of that type...

Nebeker:

Yes.

Saunders:

This was their fundamental purpose, but that group did other things too. They got the idea of consolidating the ECPD, the EJC, the various committees and organizations like that into a single organization, the AAES. The accreditation aspect of ECPD did not go into that, and they formed.

Roles of AIEE in career development

Nebeker:

To go back a bit, what was it that you found particularly valuable with AIEE in your, in your career.

Saunders:

Well, mainly the AIEE provided me with a window on what was going on in my field, and what was going on in engineering generally. The people that you were with in the meetings and New York and elsewhere, were generally the top people in that part of the area having to do with power engineering. When I was in Minneapolis as a student I generally attended the section meetings because it was educational. I learned a great deal about telephones and radio just by attending these meetings. They weren't all power at that time. I learned a great deal about power systems, and how they function. I still find that information quite valuable.

Nebeker:

Did you often attend conferences?

Saunders:

Not until after I achieved some stature in the university and had an associate professorship. I attended conferences to present papers because they were supported by the university. These papers pertained to my research in the university.

Nebeker:

Were you ever a member of IRE?

Saunders:

No, never.

Department chair at U.C. Berkeley

Nebeker:

What were your feelings about the merger?

Saunders:

I can't remember that I had any in particular at that time, because I had my hands full being chairman of the department at Berkeley. It was the third largest department in the university at that time, and it was filled with really gifted people. I worried a great deal about making mistakes that would cause the whole structure to fall apart, and then I realized it was so stable that nothing that I could do would make it fall apart.

Nebeker:

How long were you chairman?

Saunders:

I was chairman four years.

Nebeker:

And that was in the early sixties?

Saunders:

At Berkeley there's a general understanding that you'll be the chairman of your department at least once in your career. And that will be an assignment for three to five years.

Nebeker:

And you did that in the early '60s?

Saunders:

I did that from 1959 to 1963.

IEEE Educational Activities Board; continuing education

Nebeker:

I know in the late '60s you were active in IEEE.

Saunders:

Yes, I was, particularly on the Educational Activities Board. And of course when I was appointed to the board as chairman of the EAB I very much got involved with continuing education. I wrote a ten-year plan for the EAB in conjunction with Jack Kinn who was then the staff director for EAB. And I followed that all the time I was on the board, because that was written I believe in 1972. Arthur Stern was a very early supporter of that particular program, and of ideally developing a long-range plan. He was very supportive when he became part of the board of directors. Thereafter if I needed anything from the board I always said "this is in the plan," and we got whatever we needed. With the support, of course, of many of the other people on the board.

Nebeker:

Do you remember when that ten-year plan was?

Saunders:

Well the ten-year plan was for 1971 to 1982, or 1972 to 1982... I followed it up until 1980 and it was pretty much on target. We said how much we were going to do how many courses we were going to develop, and what areas we would emphasize. I called for a report each year when I was on the board, and made sure the chairman made that report to the board.

Nebeker:

And this was a real enlargement of IEEE's activities in that area?

Saunders:

Well, it was a different thrust. They had been doing largely what I call bit work. They'd put on a particular course or a syllabus that would be directed at someone's particular interest. I felt that it should be more general in nature, and that it should involve the educational community outside, and that we should be making use of the resources of the education community as well as those of the practicing engineers. That was really the result in part of my long-time involvement at Berkeley in university extension, which has to do with the universities presenting courses for practicing engineers at the university level, but not necessarily involving degree activities. Continuing education, in other words.

Nebeker:

So that was something you worked at Berkeley?

Saunders:

Yes I did.

Nebeker:

Taught courses, or introduced them?

Saunders:

Well, I was an organizer. I made sure that new fields would as quickly as possible be generated into courses. I presented my first transistor course down the peninsula, I've forgotten where down the peninsula now, but we felt there might be twenty- five people. Well, two hundred and fifty people showed up, wanting to know how to use transistors.

Nebeker:

Now, the educational activities board was established in 1967. Was AIEE doing similar things?

Saunders:

I don't recall. I wasn't active in the educational end of AIEE. I was more involved in the technical side of the AIEE.

Nebeker:

Looking back at this ten-year program, how do you think it worked out?

Saunders:

I thought it had, but, of course, I have a proprietary interest, I'm naturally going to think that.

Nebeker:

But it's very impressive that its goals were met.

Saunders:

Do you have a copy of it?

Nebeker:

I probably have seen it but I can't lay my hands on it.

Saunders:

I know Jim Mulligan thought highly of it. He said it was the first time anybody in the IEEE put forward a ten-year program and followed it through. You might ask him about that, when you talk to him later today. He was highly, highly supportive of it. Arthur Stern, and other members of the board were too.

Nebeker:

I see.

Saunders:

It eventually amounted in a general board policy, not just the Educational Activities Board but for the board of directors’ policy. And I waved it all the time when I was looking for budgets.

Nebeker:

Right. So since this had been approved, they had to carry it out. And you became a member of the board of directors in 1973?

Saunders:

1972.

Nebeker:

1972?

Saunders:

I was EAB for 1972-73, and then 1974 - hmm...

Nebeker:

It lists 1973 - 74 EAB chairman in the IEEE -

IEEE leadership positions; IEEE structure

Saunders:

I guess that's correct. And in 1973 - 74, and then 1975 - 76, by that time I was the vice president for regional activities. Then I was chosen by the board to be the board's candidate for president for 1977.

Nebeker:

During this period, 1963 to the mid 1970s, IEEE's structure was really being established there after the merger, and the regional activities board was formed in 1968. How did you move to that?

Saunders:

I don't know how I moved to it; I was elected to it without my knowledge. I agreed to do it.

Nebeker:

So you hadn't taken a particular interest in it.

Saunders:

I think I had a great interest in IEEE activities outside the country, particularly, and, of course, through my continuing activities in the IEEE I was very interested in what was happening in the sections. And I found that some sections are very active, such as the Boston section. That was really a gung- ho operation, and I thought that their modus operandi was something that should be exported to other sections. I tried to do that. But I think the main thing accomplished during my tenure was the increase in section rebates, which was a very difficult fight, in the board.

Nebeker:

That's to allow the sections to do more?

Saunders:

The sections had been receiving a dollar per member per year for eons. I tried to get them two dollars a year, but settled for a dollar fifty. We developed a formula for dispersing those monies, and I was surprised that that formula lasted a good fifteen years - a good ten years after I'd left. The fiscal volunteer of the Regional Activities Board was a chap from the telephone company in Oklahoma. His name is attached to that formula, which is rather nice I thought, because he was the one who administered it. I was surprised, I attended one of these regional activities workshops that they've had recently--the ones where they bring in section members from all over the country, all over the world. I was surprised to learn that formula was still the same one. That was maybe five years ago.

Nebeker:

And your argument there was, of course, that inflation had reduced the value of that dollar.

Saunders:

Exactly.

Nebeker:

And the sections were seriously hampered by how little they received.

Saunders:

Exactly. You rewarded sections that were active. For those that weren't very active, the formula always gave them a base amount, so they could mail out their notices, but those that were really active got a sizable rebate. It wasn't uniform across the board.

IEEE code of ethics

Nebeker:

I see. How was it in those years - this is a very general question - that you were on the board of directors, and your other activities, in making changes to policies like that, or setting up some new program, was it frustrating? You saw some results, so it must not have been entirely frustrating. I'm sure there were many good things that you tried to do that were unsuccessful.

Saunders:

- Audio File

- MP3 Audio

(238 - saunders - clip 1.mp3)

Yes, there were times when things I tried to do didn't work out, and of course on the board I had a lot of ancillary responsibilities as well. You weren’t just a chairman of the Educational Activities Board, but you might be the representative of the Fellows Committee to the board. I guess I gained a little notice for being an adept politician, because I'd been involved in academic politics for so long, and the board was not a great deal different from academia. You compromise here, and innovate there, and pretty soon you've got something going. For example, I was the floor manager for the code of ethics. The USAC--which ultimately became USAB, it was then called the United States Activities Committee--as I recall, put forth a code of ethics, and when it came to the board it was outright rejected. But then they realized that it was a necessity, because the only code of ethics the IEEE had was one the AIEE had put together in 1912. I thought that the format that the board had put together was worthwhile. We sent it back to USAB, and they got it back again approved. I don't know how many cycles this went through. At one point the board decided that they would have to put it together. It was done this way! The board would appoint a committee, and then it was natural the committee would make a report. I've forgotten the exact details of how I got involved as the floor manager for the thing, but I think the committee felt they'd done their work, and it got to the board. Various board members had objections. I developed a technique I'd learned from Jim Mulligan, which was to move that the matter be tabled temporarily while we had a luncheon meeting, and a drinking meeting in the bar. I would go to these people and say precisely how we should change this, and they'd come in with wording. I think I had a pretty good feel for what the board would accept. And finally, after about three iterations like that, at one meeting of the board it was adopted with one dissenting vote, the original code of ethics. I was quite pleased about that. I did other things--but that was probably the most significant one that I did.

Nebeker:

Was the IEEE ready enough to change in those years?

Saunders:

Yes. The board was ready at that point. And I felt that the four principles that were developed in the IEEE code of ethics were very sound. I could support it with all my, limited debating ability. But the fundamental principles of being--taking care of the client or your employer, taking care of your colleagues, taking care of yourself by education, continuing education, and then taking care of the public societies--I thought those were, and I'm not sure I have them in the proper statement or order, but those I felt were very strong priorities. Then when Ivan Getting came in, he found a flaw in it, which was I think a very good one, and this was that we cannot say all engineers, we can only say IEEE engineers, because the IEEE only has a say in the activities of its members. And that change was made then. I didn't like that change, but I felt that it was necessary to accommodate the realities of engineering.

Nebeker:

Yes. I also was impressed by that kind of simple overview of the purposes of the code of ethics.

Saunders:

We read the National Society of Engineers’ code of ethics. That was directed towards how you should behave yourself if you were a consulting engineer. Basically that's what it was, and we felt that was only one small facet of what a code should be. I think our own, I think IEEE people showed a great deal of statesmanship in developing that code. There was a lot of statesmanship in those days.

Nebeker:

And, now that was in the early 1970s, approved in December 1974.

Saunders:

Was it that early?

Nebeker:

See here.

Saunders:

I'm surprised it was that early. I don't have a date on it.

Nebeker:

Well, I'm quoting from Mike McMahon’s history of the IEEE, which is generally reliable so far as I can tell. Now was that a product of that particular time? I mean it was a climate of anti-technology, a bit, at that time.

Saunders:

I didn't sense that that was a driving facet, but I did have the feeling that these people who were doing whistle blowing needed something to lean on, and to support them. We had several cases brought to our attention, and we suddenly found, well we didn't have a code of ethics. How could we support them if we didn't have it down in black and white? That was where USAB came into the picture, and they worked on it hard, and did a lot of work, and produced something that the board could then take and modify that to the satisfaction of all members of the board. Remember that the board was not particularly USAB-oriented. There were several people on it who worked for corporations, who felt that the United States Activities Board was not doing things that they wanted it to do. That was an undercurrent that ran through, and I felt that someplace there was a balance that could be done.

Nebeker:

Yeah, and get agreement on -

Saunders:

There were other members of the board who felt the same way. Carl Lesser, for example was another. Those of us in academic positions, I think, were probably more familiar with debate, and give and take, compromise, than people in industry. I remember Joe Dillard saying at one time that the difference between industry and university was that in industry we sit around the table and everybody puts forward his viewpoints, and you pound the table and move hard for your position, and after half a day of this the vice president will stand up and say, well, gentlemen, this is what we're going to do. And everybody says yes sir and goes out and does it. And what do they do at university? Same thing, they argue, and the dean stands up and says, I like that, this is what we'll do, and everybody else goes out and goes to see the president to shoot the dean down.

Nebeker:

So you've got to be a better politician in academia.

Saunders:

Yes. Well that's my theory anyway.

Nebeker:

And I gather you're happy with the way the code of ethics turned out?

Saunders:

Yes. I think its language is a little more flowery than it needed to be, but that's life.

Evolution of IEEE activities; pensions

Nebeker:

How did you feel about the move of IEEE into those non-technical, non-educational activities?

Saunders:

Well, there was a sizable body of members that was interested in that. Some of those activities were beneficial to all engineers, like the issue of portable pensions, which we still don't have. I testified to Congress on that, once or twice. Many of the members of Congress were very supportive of it. But it never came about. Academics all have portable pensions. I couldn't see any reason why engineers shouldn't have it. And so I could support that part of our activities very much. But of course, there were a few people who were concerned with issues that were highly controversial, that maybe even to this day have not been completely resolved. But that issue of the pensions was something that I felt strongly about. It was a social issue and it was very important to engineers, especially employed engineers in industry.

Nebeker:

And you thought it was appropriate for IEEE to -

Saunders:

I felt it was, as long as the membership thought so. I spoke and interacted with sections - I tried to move out into the sections as much as I could and find out what the thinking was. In fact when I was president I did two or three tours of regions. I would spend five days doing region three, for example, and I'd go with a district, with the regional director, and I'd go to region five and region four. I was about to do Region Seven, and feel at home with my countrymen. I had to postpone that, and it never did happen, because Schulke had resigned, and we had to install a new, or an acting general manager and executive director, who turned out to be Dick Emberson. That was a very time-consuming operation, and I was very much dismayed when his resignation came out during the first months.

Nebeker:

Schulke's?

Saunders:

Yes, Schulke's resignation, in January of that year.

Nebeker:

And that was the year you were president, in 1977?

Saunders:

That was when I was president, yes.

Emily Surjane

Saunders:

I'll tell you an interesting story, which not very many people know. Most of the people are now dead, so I can talk about it. We, the executive committee, in June I think it was, when we met, I can remember we were in some dingy hotel in New York. The executive committee had the idea of asking Emily Surjane to do it. Now I thought that was a wonderful idea, because she might have -

Nebeker:

To become the executive director, general manager?

Saunders:

To become the executive director. Most of us who knew Emily knew her mostly for her support as a staff person, and others who knew her better than I did thought she was a tough cookie, and it turned out she was. The executive committee, and I certainly supported the idea, asked me to approach Emily, to do the job. She thought about it over night, and she said, well, she said, I appreciate the honor, but she said I really don't know enough about publications. And I think the mistake I made was not insisting that she take the position, because Emily Surjane was the IEEE abroad. When you get out in Europe, and Asia, if anyone has a problem in those countries they write, and Emily was the one who answered them. This was before she became a corporate secretary, or the staff person for the board. She would tell them how to solve this particular problem. So Emily became the IEEE, basically. She was well thought of in the sections--I found this all over. So the mistake I made was not insisting, because if I'd insisted that she be named she would have been a good soldier and said I'll do it. And in retrospect I think she would have been very successful at it. But I had to -I felt I had to give in to her view, and she'd thought it over very thoroughly and very carefully, as she would always do. She was a very meticulous person.

Nebeker:

And you think there was support for this.

Saunders:

Oh, yes. Well the executive committee would have supported it, no question. The executive committee had the power to appoint the acting person. The assembly had to do the appointment at the end of the year, of course, and I felt if Emily had been in there for six months she would have peering just like Dick Emberson. So, then they went and said, let's ask Dick Emberson to do it. I was opposed to that, because that would tear down the structure that he had developed in technical affairs, which was a very difficult job, I felt. But maybe it wasn't as difficult as I thought it was, because his successors did very well, and Dick did well as the acting general manager. Then the first thing that Ivan Getting did was to propose that Dick be made the executive director and general manager, and he was for several years.

Nebeker:

Just a couple of years before -

Saunders:

I guess it was two years. Then he retired. He was close to retirement age. And so was Emily, too. But that's a story that very few people know about.

Nebeker:

It's very interesting. I know that Thelma Estrin mentioned Emily Surjane, in connection with some commendation she received from the board when she did retire. Thelma thought that the board - in their language anyway--seemed to treat her as a mere secretary, or something, when in fact she was more of a director, a manager.

Herbert Schulke

Nebeker:

What can you tell me about Schulke's resignation? His published statement for resigning was that the designs created by the USAC at the time were such that he couldn't do the things he hoped he'd be able to do as general manager. What's your understanding of his dissatisfaction?

Saunders:

There was considerable dissatisfaction on the executive committee at least with the way he handled the [end of side one]

Saunders:

[side two begins] because the Regional Activities Board didn't have much staff, we had a director and a small secretarial staff, maybe two or three people, and then the person who handled the student activities was under the Regional Activities Board. So I wasn't particularly affected, but there were other vice presidents that were affected. He may not have been as politic as he should have been in downsizing the staffs. But you know, any time you do that sort of thing, you're going to be in trouble with a lot of people. I don't know what happened-- what transpired in the smoke-filled rooms--because I was not included, and I think that this was to protect me as the incoming president. I didn't know I was going to be president until December 1st. You see, there's no president elect operation, there's an election in November, and I didn't know what was happening to me until I was picking up my baggage, I think, in Atlanta Airport, and somebody said well you've been elected president. That was from another member of the board, and that was the first I heard of it. But apparently a telegram had gone out the night before to all the board. I'd already left home to get to Atlanta. But I was not involved in the backroom operation at all, so I can't say anything about that.

Nebeker:

Okay.

Saunders:

But I do know that there was some activity, particularly on the part of the more senior members of the Executive Committee.

Nebeker:

So this may well have been more his being forced out.

Saunders:

Well, I'm not sure it was being forced out as it was giving him notice that he was abdicating. So he bit the bullet and pressed on.

Nebeker:

Was that difficult? I guess he continued until the middle of that year.

Saunders:

Well, I asked him to, and I think that may have been a mistake. I asked him to continue on for six months, because that what's we do in academia. If somebody says I'm going to resign you say, well, fine, finish out the year. And they do, usually. For example, we've got a man here now who's going to become the chair of the department at Virginia Tech. I just met him the other day on the stairs, and he told me he'd be here until the end of the year. This is a fairly common procedure in academia. I think in the IEEE it may well have been a mistake, it probably should have been done in ten days, or something like that. But that was my error, if it was an error. I asked him to stay in there and continue until the middle of June. He refused to continue further than, I guess the date you have in this minutes, it was [something] twenty-two. That's what held up my proposed trip across Canada. So, I really wasn't too versed in what was going on until the time came, and so it was really Schulke’s doing. I said, at the time, if there's anything an infant president doesn't need it's the resignation of his executive director!

Nebeker:

How did that work out, that first half-year when he was still there?

Saunders:

It worked just as well as when he was gone. I didn't see any revolt among the troops or anything like that. Everything went along fine, and each person did his job. It was just that policy for staff was not accepted. It may have been that I was so busy with other things that I was not too aware of what was going on among the staff. It could be that I have a blind side on that.

Dick Emberson

Nebeker:

Okay, and then Dick Emberson took over in the middle of the year.

Saunders:

Yes, he did.

Nebeker:

How did that work out?

Saunders:

Well, Dick was an old-timer in the IEEE. He knew the institute, he knew the people, and I think the people respected him. But it wasn't that he didn't have his problems too. I wanted Dick to go with me to China. I thought it would be giving more prestige to the team if he were on it, but Dick felt that he couldn't be away from the headquarters for the three weeks, almost four weeks, that was required. He felt that having the president and the executive director out of the country at the same time was a bad idea. I think maybe he was right about that. I didn't argue with him for very long.

IEEE presidential elections

Nebeker:

Okay... maybe we can take a step back in time. Your candidacy for president - that was one of the first contested elections, wasn't it?

Saunders:

No, there was -

Nebeker:

Well, not one of the first, but certainly -

Saunders:

The IRE had a contested election one time, as I recall, but I don't think the AIEE ever did. It was a first in the IEEE, the contested election. It was a three-way race. Irwin Feerst was a perpetual candidate, I might say, and I don't know whether Joe Dillard ran against him or not. But he certainly got enough petition signatures to enter the race, as did Bob Rivers. In a sense I was pleased to see Bob do that, because that divided the enemy. This is a British system, you know. Get as many people as you can, and they divide and fall.

Nebeker:

I'm not sure if it was about this election, but maybe so, that Feerst said it was deliberate board policy to have a third candidate to split the dissatisfied vote.

Saunders:

Oh of course Bob Rivers was a board member.

Nebeker:

Well, this would lend support to Feerst's claim.

Saunders:

But, and of course Carl Bayless was River's running mate, and he won. And I felt badly for Rob Briskman when Carl won, but I recognized Carl's talents, because he'd been a regional director, and he was a good regional director. But Rob Briskman worked very hard for the Institute, mostly through the technical end, and I felt badly about that. Of course we campaigned together, so we had a common bond, but then they elected him treasurer, so he was on the board still.

Nebeker:

Was it clear going into that election that there was considerable support for Feerst and Rivers?

Saunders:

Well, we knew that the election would split. If it had been two people, it probably would have been forty-five or fifty-five, no matter what. And this way it was--what was it, forty-two, thirty-eight, or something like that. That wouldn't add up to a hundred, but something of that general order. But I think what made Feerst unhappy was the popularity vote. You vote for all the people you think would be acceptable for the IEEE.

Nebeker:

Yes, that system.

Saunders:

He felt that was a clear anti-Feerst approach. Maybe it was; I wasn't privy to that procedure at all.

Nebeker:

To an outsider it looks like there must have been some groundswell of discontent with the board, when there was this contested election and the two non-board members -

Saunders:

Well, there was a large amount of discontent there were a lot of unhappy people. At any meeting I went to I was always on the defensive, defending the board. But the people who are the opposition are always the loudest. We see that in national politics, and the IEEE is no exception. The people who are trying to get the IEEE involved in social issues, and member issues that had to do with their economic wellbeing, were very vocal. But the problem with a candidate who is elected by a petition, whose petition is borne out by the electorate, is that he or she has not been on the board of directors, at that time anyway, before he or she becomes president. I think it would have been impossible for me to be president without having spent four years on the board. It would have been very difficult. And I often think of Leo Young, when he won a contested election -

Nebeker:

He was a petition candidate?

Saunders:

He was a petition candidate. I think he must have had a very difficult time, because of that. He did have that one-year as president-elect. It wasn't an utter disaster for him. But it would have been, I think, an utter disaster for the Institute if Feerst had been elected, because he had no experience in management, he had no experience in balancing a budget, and he had no experience in handling people.

Nebeker:

Did you know him, get to know him at all?

Saunders:

I didn't know him at all well. I just tried to hold him off at arm's length I felt that he just had no experience he had never fired or hired anybody. And I think that helps in the job.

Nebeker:

Ivan Getting told me on the phone that he was in a sense recruited to run the following year because there was some fear that Feerst would -

Saunders:

Well, he showed up very well in the three-way race, and I think they were afraid that he might win the following year. Joe Dillard was chairman of the nominating committee, and he brought in Ivan Getting's name, and of course I knew of him, I'd never met him, of course, up at Aerospace, where I was doing some consulting work, but I knew of him, and I knew that he was highly respected in his field. I felt that if he chose to run as president, he'd make a good president, and I think he did. But he did not reflect the concerns of the USAB.

Nebeker:

Yes. Well, it must have been the case that Feerst wanted IEEE to go further in the direction of non-technical professional activities than the board was comfortable with. Is that right?

Saunders:

Oh, I think you're being too charitable. He was a true revolutionary, as far as I could see.

Nebeker:

Some of his proposals about keeping foreign engineers out, those were fairly radical. But can we be specific here about what professional activities you felt - you mentioned the pensions, the portable pensions thing, and things that, where you would draw the line and Feerst would go further?

Saunders:

Well, for example, he would testify in congress against foreigners being admitted to positions in the U.S. because it would be denying a US person a job without any regard to the qualification of the person. Many of the things he was advocating he'd never have got through the board. It would have been frustration for both him and the board for the whole year.

Nebeker:

It certainly would have hurt IEEE's international -

Saunders:

Image. It wouldn't have hurt IEEE, but it would have hurt the image.

Nebeker:

Well, yes. It would have hurt IEEE if any of these policies of Feerst's were approved.

Saunders:

That's right, but the chances of them being approved were very low, because he had no constituency on the board. The board's candidate has a constituency right away of half of the board, because they're the half that approved the nomination. The incoming people are not all that different from the ones that are leaving, so it's a self-perpetuating organization, and it changes very slowly, which it should.

Nebeker:

So the radicals would say this is just a structural guarantee of conservatism, on the part of the organization. But you think it should change slowly, anyway.

Saunders:

Well I think it should change slowly, because at that time it had two hundred thousand members, roughly, and a very wide spectrum of interests, cultures, you name it, all throughout the world. It's like taking one of these great big trucks on the highway - if you suddenly turn the wheel to the left it's going to go skidding down the highway and crash. And I wasn't at all interested in having it go skidding down the highway and crash. Things have to be done very slowly and gently.

Saunders' IEEE presidency; staff and successors

Nebeker:

How was the year as president for you in terms of the demands on your time? How did it disrupt your other work?

Saunders:

Well, I gave up most of my consulting activities during that year. Seemingly it was a good time to take a sabbatical from here.

Nebeker:

For the whole year?

Saunders:

I think for half the year. And I used the travel abroad; I was then interested in a levitated transporter, using electromagnetic methods of lifting the vehicle off of the ground, no wheels on it or anything. And so I was able to visit in Germany, and talk with people there, and also in Japan, and talk with people there, during the time I was president. I visited the Japanese railway people when I was on the way to coming back from China. And I talked to the Germans, and I went over to the region eight meeting in Spain. So I was able to justify the intellectual refreshment, which is what a sabbatical is supposed to be about. It seemed to me that that was far down the road, and it wasn't going to happen for a long time, and it hasn't. Whether it happens in the future depends a great deal on a variety of factors.

Nebeker:

Were you surprised at how demanding the job was as president?

Saunders:

No, I didn't find it impossible or anything like that. I guess my general feeling is that if you accept something of that general type, you do all you can. And it has to be all you can do. And I did. I visited; I tried to visit sections that had never seen a president before, or student branches that had never seen a president. I wanted to do that for all the regions, but that was an impossible task. I was on the go a good deal. I did a hundred forty thousand miles on aircraft that year. I did a lot of flying. They reduced the size of the Saunder's foundation capital, at that time, because when I took my wife at that time she was not supported. I complained to the board about that, and sure enough for the next year's budget they put in an item for the president's wife.

Nebeker:

That's what your complaining got. When did the changeover to the president-elect, president and past president take place?

Saunders:

That occurred about two years after I left the board. Those things move at glacial speeds.

Nebeker:

So you were junior and senior vice-president.

Saunders:

Yes. And I think the year after that--I've forgotten now the details--but very soon after I was president they changed it over. But it took, I guess, three years for that to happen, because two people that were elected, including my successor, Ivan Getting, he would be senior vice president in 1980.

Nebeker:

Yes.

Saunders:

And so that, I think, was the first year that they had the president-elect.

Nebeker:

I see. Did you continue to be quite active in those two years after your presidency?

Saunders:

Well, I did, yes. Junior past president is really the conscience of the current president, like Joe Dillard was for me and Arthur Stern was for Joe. And I think, I might have helped Ivan Getting get a good deal, but I'm not sure. He was able. Anyway, after he'd been there a couple of months he knew which end was up pretty fast. You don't get to be president of Aerospace by being a dummy.

Nebeker:

How did you feel about the staff support that you got?

Saunders:

I had it. I had it. That was because I've always considered the staff to be as important as the prima donnas. If you go around this place, you'll find I'm more highly respected by the staff than I am by the faculty. Part of that is because I feel very keenly that the staff are what makes things work. It's true in the university, it's true in the IEEE, and I'm sure it's true elsewhere too. So I've always had a high respect for staff members anywhere. And they know it, and they know I respect them. And they respect me for that.

Nebeker:

How did - well, I guess we talked about this a little bit with Schulke. I was going to ask how the headquarters staff seemed to function in that year or so.

Saunders:

It seemed to function reasonably well. Of course, you can't ask Dick Emberson. It'd be nice if you could. You know Eric Herz was around a good deal. He was on the board in the 1970s, and he was very active in technical affairs, and also he was active in USAB affairs as well. And he provided a rational approach to these issues. He of course had had a lot of industrial experience, with General Dynamics, down in San Diego. And I thought very highly of him. He was a real gung-ho IEEE person. His section down there had more conferences, because they went out and worked for those people in the conferences. As a result, they got a little change that went with the conferences. His section was one of those that I held up always as, here, if you work this way - but it's pretty hard to tell Cedar Rapids people to do this, because they're not in San Diego!

Nebeker:

Were you part of the committee that appointed Herz, or recommended him?

Saunders:

I recommended him early on to, I think - I've forgotten now whether he came in. How long was Dick Emberson there? Was it two years?

Nebeker:

I think it was just until the beginning of 1979 -

Saunders:

Well, you see, I was still on the board at that time.

Nebeker:

Yes, I think the beginning of 79 was when -

Saunders:

I think Ivan Getting was chairman of the search committee, and he recommended Eric Herz, and I jumped on that bandwagon immediately. Because I felt that here was a person who had been through all the steps of the IEEE. He had managed people, and made budgets, he had produced results. It worked out that way too.

Presidency highlights; trip to China

Nebeker:

We don't have a lot of time left. One thing, at least, in looking at the Institute at that time that looks like a major event of your presidency, was the China trip. This was the first major exchange between the U.S. and Communist China. That's fairly well documented.

Saunders:

It should be!

Nebeker:

There's the trip report, and quite a few articles in Institute, but there are probably things that didn't get into there that you could tell me about. Anything comes to mind?

Saunders:

Well, I think I told you over lunch about -

Nebeker:

Well, we'd better -

Saunders:

About the route... but I had nothing to do with the selection of the delegation. That was done by the international, some committee of, I think it was a [something] committee. They chose the people, and apparently the Communications Society had entertained some Chinese a few years before, which was why the Communications Society was named the head group to go. Amos Joel was past president, I guess, and this chap from Richmond, California. I can't think of his name now. But he was the current president of the Communications Society. Most of the delegation was made up of people the British call “light current people.” I'm called “heavy current.” I think that's an elegant term, I like that very much. I have a friend in Britain who was appointed professor of heavy current engineering at the - number one engineering school in Britain--Eric Leithway, who's been a good IEEE member, by the way, too. I had nothing to do with the choice of Eric, other than to support it enthusiastically.

Nebeker:

What other events stand out in your mind from that year?

Saunders:

By the way, there was one thing you sent, the very first thing you sent, with a picture of William Saunders on it. That Bill Saunders is the director of advertising for Spectrum. And every once in a while I get a check from the IEEE for Bill Saunders, I haven't had one recently, but at least they reimburse me. One of the things that I think you might be interested in, is that I turned in the largest surplus ever in the history of the Institute. There was a big flap at the beginning of the year, we were going to lose money, and because I was an academic, I was going to be the guy that lost more than anybody else. But it didn't work out that way... Once a couple of simple things were done, I let the staff know that I would not be favorable to an increase in their salary for the next year if they did not bring their expense budget in, on the dollar. You cannot control income, but you can control expenses. The staff was responsible for the expenses. And the staff delivered. They delivered on budget across the board, right down the line. I was lucky; I'm the first to admit it. The publications sold like mad, the conferences all made money, and so it went. So that was something of considerable interest.

Nebeker:

They need to put you in charge again.

Saunders:

Another thing was, when I walked into the meeting--there was a picture back here that I hadn't seen, it's nice to have--when I walked into the board meeting, I said, I rule by Roberts' rules, and this is my ruler. Well that of course created a great deal of laughter, but I really meant it. Because I had chaired an all university faculty conference, which is kind of something called by the president of the university, I had chaired a meeting where the resolutions are adopted, and I was the co-chairman of the whole thing, and the people that were chosen had come from all the different parts of the university, the medics, the history departments and so forth--two hundred and fifty of them. We were at Davis. I ran the meeting that adopted the resolutions. And I did it strictly by Roberts’ rules. And there were twenty-five lawyers there too. And I had an interesting experience on the board, on that score. I could sit there at the front of the table, by looking around at the people, and the other, the president and vice presidents, pleading their case, I could tell from the looks on their faces just exactly where they stood. That was the year I saw the slippage in the influence of USAB, I felt. Now it might be nobody else felt this, but I felt it. And I had one experience where one member of the board made a personal attack on another member of the board. And I used my smaller gavel. And I found out early on that nobody can talk over a gavel, nobody. I mean nobody, I don't care how loud their voices are, can't talk. This is because gavels have such a sharp tone. This blocks people's hearing. And I gaveled him into silence, and I said I demand an instant apology for your remarks, which are improper for a member of the board to make to another member. And he apologized. After about three seconds he apologized on the spot, just like that. And some of the observers felt that that was quite a show. But I would not stand for any thing like that. You could attack a person's ideas, but not his person. I don't know who said that in American politics. But that was an interesting thing that happened on the board too. Oh yes, and I took the board to Minneapolis, to my favorite hotel in Minneapolis, the Radisson Hotel, and it was a dump. So they presented me with an old shoe at the last meeting! We had quite a flap over registration that year, and it didn't get resolved by the end of the year, but there was a general feeling among a large number of people, and even the board felt, that it was appropriate that all members of the profession be registered. I'd had no objection, since I'd been registered since I was grandfathered into the California listing. But it finally got resolved, that it was still I guess really an option, but it was still -

Nebeker:

Very much debated.

Saunders:

It was a very difficult issue, and it raised a lot of people’s blood pressure. Joe Dillard was very encouraging of the combination of the Engineers’ Council for Professional Development and the Engineers Joint Council, and all their activities into a single umbrella organization which would be able to do some of the things more economically than individual societies could do. I'm not sure that that ever came to pass, but it may some day. It's still in existence, I notice. The Power Engineering Society was thinking of withdrawing from the IEEE and forming their own society with the mechanical engineers, who--they're involved with hydraulic turbines, or steam turbines--and I pointed out to them how many members they would lose, because I looked at the number of people in the PES that had a joint membership with other societies, and I said not all these people are going to go with PES. Furthermore, the services you get from the establishment of the IEEE are worth a great deal. Your cash is all handled, your dues are collected, they're disbursed, and so forth. After thinking it over for a while, they decided to drop the whole idea. I may have influenced them a little there. I also got the Audit Committee to do something more than just rubber-stamp the CPA's audit report. I got them to be an oversight committee. If we received some indication that some entity within the IEEE was not doing its job, you could sic the audit committee on them, and they would do an in-depth study. I don't know if that's still being carried out or not, but for a few years there, that was the way the audit committee was used. That was something I was able to do. But in the main, it was a wonderful year.

Nebeker:

Thanks very much