Oral-History:Per Bruel

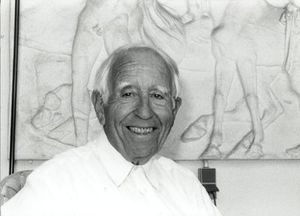

About Per Brüel

Per Brüel studied at the University of Copenhagen, working in Peder O. Pedersen's laboratory beginning in 1932 and producing a doctoral thesis on room acoustics. Brüel was drafted into the Danish military in 1939. Following the German invasion of Poland, Brüel worked with the Danish army on the problem of radio transmission with armored cars.

After the German invasion of Denmark, Brüel was released from the Danish military and continued working with Pedersen and working on his doctorate. In 1942 he started the Brüel & Kjær instrumentation company with Viggo Kjær, a colleague from the University of Copenhagen. In that year, Brüel also left German-occupied Denmark for Sweden, although he returned to Denmark throughout World War II, carrying his dissertation papers and transporting documents secretly for Niels Bohr. From 1944 through 1948, Brüel was appointed at the University of Gothenberg, building an acoustics laboratory.

In this interview, Brüel describes his work with P.O. Pedersen, his military service, the influences of World War II on scientific work, and the Brüel & Kjær company. Brüel describes the emergence of this company; its place in the post-World War II economy; its structure; and the development, marketing, and sales of its influential products, including the level recorder, condenser microphones, and the noiseless filmstrip.

For further information see Viggo Kjær Oral History.

About the Interview

Per Brüel: An Interview Conducted by Frederik Nebeker, Center for the History of Electrical Engineering, 18 July 1996

Interview #304 for the Center for the History of Electrical Engineering, The Institute for Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc.

Copyright Statement

This manuscript is being made available for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the IEEE History Center. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of IEEE History Center.

Request for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the IEEE History Center Oral History Program, IEEE History Center, 445 Hoes Lane, Piscataway, NJ 08854 USA or ieee-history@ieee.org. It should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user.

It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows:

Per Brüel, an oral history conducted in 1996 by Frederik Nebeker, IEEE History Center, Piscataway, NJ, USA.

Interview

INTERVIEW: Per Brüel

INTERVIEWER Rik Nebeker

PLACE: Holte, Denmark

DATE: 18 July, 1996

Childhood, family, and education

Nebeker:

Tell me where and when you were born, and a little about your family.

Brüel:

I was born in Copenhagen. I was the eldest son. My father was a forester, and in the family it was a tradition that the eldest son should be a forester also. They came originally from Saxony in Germany, and through seven generations the tradition developed of the oldest son becoming foresters. I didn’t like that and there was a big family scandal.

We lived at that time over in the South of Jutland. That was away from schools and towns and everything. It was a big forest area. Consequently, I only had very little education and as there was no money to go to the University. When I got older I was sent away to be a blacksmith.

Nebeker:

Sent to where? Some city?

Brüel:

It was really a power station that offered education. But after a year the manager of this power station thought I should go to the university. Thereafter, I went to the technical university in Copenhagen. After that I became interested in aerodynamics, electronics, and acoustics.

Postal and Telegraph Office, radio studios

Brüel:

That was in about 1929. We built the post and telegraph office, and were responsible for all the radio studios. They built this building for radio studios called Steerkastel, and it still exists in Copenhagen. It is presently connected with the Royal Theater, and is a good studio for all kinds of music and theater too.

Nebeker:

Is it mainly a radio studio?

Brüel:

Yes, but also there was also a theater so the Royal Theater used it as a secondary theater.

Nebeker:

Was P.O. Pedersen consulting on that?

Brüel:

No. He was a very brilliant physicist; he would have been able to easily see the problems that the other men could not. The chief engineer, Christiansen, was responsible for the fiasco that developed in the post and telegraph. He eventually took his own life. I don’t know if it was because of the problems at the station, but we thought it was in connection with all the criticism that he received. After that P.O. Pedersen said, we can’t have this amateurish activity going on. He believed we should make a science out of it. So, we started an acoustic laboratory.

Acoustic laboratory; communications studies

Brüel:

The United States already had one. There was one in California. It was the first acoustics lab in the world. Under Hitler, the Germans made quite a few because they thought there was something they should as part of their war business. Therefore, Professor Ervin Meyer he was a very famous in building acoustics, underwater acoustics and so on, he came and built a beautiful laboratory in Göttingen. After Meyer left Manfred Schröder took over. He just recently went on pension.

Then P.O. Pedersen got a man named Jura Danes, who was an electrical engineer, to join in 1931. He was the first man to have helped P.O. Pedersen build this laboratory. That was the foundation of the Danish laboratory.

Nebeker:

When did you start there?

Brüel:

I started in ‘32, but that’s when I was completing what we called a Ph. D., but that is the equivalent of a master of science today. That was my transition into the field. It took about five months to work through, and P.O. Pedersen, who was my mentor there, had a group of about twenty people. He picked some of the students he liked most to try to make them work on his ideas.

Pedersen asked me if I could make my work on wall transmission. He had the idea of putting a tube with absorbing material up in front of the wall and having a microphone there. Due to the set up there would be no reflections because the tube was absorbing the [unintelligible], so you picked up only the sound that was coming through the wall. That was my first project there.

Nebeker:

What was the line that you followed at the technical university?

Brüel:

I was in communications.

Nebeker:

What was your intention at the time?

Brüel:

My intention was to create a system that did not need speakers, but I started off as an amateur.

Nebeker:

I see, so you had your own receivers and transmitters as a youngster?

Brüel:

Yes.

Nebeker:

Did you build it yourself?

Brüel:

Yes, of course. At that time, they were very crude instruments, made with keys.

Nebeker:

Could it only do Morse code?

Brüel:

Yes. I did not come up with a microphone at that time, but I was only fifteen years old at that time.

Public address systems

Nebeker:

Around 1930 public address systems began to be common place. Did that make the need for good, loudspeakers a scientific topic? And was that your original intention?

Brüel:

It was, and then I got a book when I was, thirteen or fourteen years old, where P.O. Pedersen had written an article called, “Different areas of technology.” It was very fascinating. P.O. Pedersen then published a book of his lessons. The book was rather advanced, but it intrigued me with lesson on how to make various things, like tape recorders and the Poulsen arc.

Nebeker:

Did you get to know Poulsen?

Brüel:

Yes, very slightly. He was very old at that time, and starting to be a little senile when I saw him the few times I did. He came to the laboratory from time

P.O. Pedersen

Nebeker:

How was P.O. Pedersen as a teacher?

Brüel:

I liked him very much, he was brilliant, diplomatic, and he always got his point through. He was a dean of the university for twenty years, and had the ability to let other people design their own jobs. In a sense, one of his qualities was at delegating. In the end, however, he would take credit for your work.

Nebeker:

Is that right?

Brüel:

Yes, that was what the younger scientists said at the time. I have written a whole book, but only his name is on it, and I have written every word of it.

Radio transmission in armored cars, WWII

Brüel:

When the Germans invaded Poland on the first of September 1939, the Danish army was called in. They called several universities, and as an electronic engineer, I got transferred to a laboratory for making radio transmission in armored cars. The boss of that department liked to make speeches at electronics societies and I wrote several of his speeches. There was a very funny rumor going around at the time that the British and maybe even the Germans could pick up the radio waves, and consequently the position of an airplane. The department head comes in and said “That’s impossible, I should like to make a speech in the electronics society about that.” I said, “Yes, let me try to work on it.” So, I calculated the data and found out the most amount of power you get from a radio station, you can also get from the reflection of an airplane.

Nebeker:

Did this allow someone to accurately assess the direction of the plane?

Brüel:

Yes. I found that is the biggest power you could get. Even if you could direct it in a very good way, with the best antenna, you still get too much power up there; after that it gets reflected down and that signal was below the noise signal of any radio tube. So, that was scientific proof that it was not possible.

Nebeker:

Well, a lot of people thought that radar wasn’t possible. How do you explain your finding given that?

Brüel:

Yes, but you could prove it! You could find out that you get megawatts out of the klystron, even for short time.

Nebeker:

What year was that?

Brüel:

It was just before the Germans invaded Denmark, so it must have been in February ’40.

Nebeker:

So what year was it you completed your initial studies at the technical university?

Brüel:

That was in January ‘39. Then I went three months as assistant for Professor P.O. Pedersen, and then I was drafted to do the radio for the military for a year.

Instrument to analyze a fraction of an octave bandwidth

Nebeker:

Downstairs you showed me a picture of an instrument you constructed. Was that in this period?

Brüel:

- Audio File

- MP3 Audio

(304 - bruel - clip 1.mp3)

Yes. The instrument was the first instrument to analyze a fraction of an octave bandwidth. This told you what the actual frequency band was, and how it increased when you got up in frequency. Such an analyzer did not exist before that. We only had heterodyne analyzers, where the most famous was General Radio’s heterodyne analyzer, but that had a fixed bandwidth.

I got the idea from an article in the last issue of the German Acoustical Society that came to Denmark before the war. In it was an article from, I can’t remember the name of the thing, that showed a network which you can use in a feedback loop for an amplifier. It was done in such a way that it only consisted of three condensers and three transistors, and it could stop a single frequency and all the other ones going to full feedback, without things changing. This allowed a reduction of the amplification.

I knew I can use that because in Denmark we had factories that made very stable condensers, and also a factory that made very nice wire bounded potentiometers. Between the two, you could make an analyzer where the frequency increased in octaves by changing the condensers, and inside that band, you can change the resistor, continuously, over a complete octave. The result was a very nice bandwidth over the whole thing.

This activity was not so tremendous, because I was using small, battery driven tubes, with not too much an amplification. Also, the accuracy of the potentiometers was within limits, it should be about one percent, and that was the maximum accuracy you can have. If it went outside that range, the whole thing would start to oscillate, making it difficult to make mechanically.

Nebeker:

And why did you develop this instrument?

Brüel:

Because I was very interested in acoustics, and could see there was a need for an instrument to analyze all kinds of noise in the frequency range.

Nebeker:

Was there a particular application in your job where this instrument was useful?

Brüel:

No, there was general interest in emission techniques.

Doctoral studies, room acoustics

Nebeker:

What happened when the Germans came in? You were then released from military service?

Brüel:

Yes, and I continued on with being assistant supervisor to Professor P.O. Pedersen, and work on my doctorate there.

Nebeker:

What more precisely were you working on then?

Brüel:

I was into room acoustic. That was what my doctor’s thesis was about. At the same time, the radio studio, Steerkasten with the bad acoustics, was making the post-telegraph transition. So they started building a new station. At a very young age, I found myself helping the man that had the responsibility for the acoustics there. He was a brilliant professor in building statistics [architecture].

But as he was also a member of a singing choir, and as such had an understanding of acoustics. So he asked me to help.

Nebeker:

Do you think P.O. Pedersen recommended you?

Brüel:

No. It was another Professor [unintelligible], I remember his name, at university who worked with building statistics.

Nebeker:

And how did that acoustic work go?

Brüel:

Excellent.

Nebeker:

Were there the theoretical tools at the time to assist you?

Brüel:

Yes. We had this Neumann recorder, which was a very good tool. We could make very nice reverberations times, so we had really good instrumentation for that. And we also had the Usatz, which was a bass drum.

Nebeker:

How long did that project last?

Brüel:

It lasts until the end of ‘42. Then the radio house was finished. But we didn’t want to inaugurate it because the Germans were there. Consequently, we just started working.

The official inauguration was not done. Professor P.O. Pedersen died, and I had more or less finished all the work in my doctor’s thesis, and because I had so many friends in the opposition and I joined. Thereafter we left for Sweden, so I went over to Sweden in the end of ‘42.

Swedish glassworks lab employment

Nebeker:

And what was the reason for going to Sweden?

Brüel:

Because I was living in a country occupied by Germany, and I couldn’t find the work that I wanted to do.

Nebeker:

What happened when you got to Sweden?

Brüel:

When I got to Sweden I immediately got a job. I worked in a big company called [unintelligible] who made glassworks under a French license to make all of these French patterns. They wanted me to make acoustic damping and absorption materials because that was completely unknown in Sweden.

Nebeker:

Were you in some kind of a research laboratory?

Brüel:

Yes. The company was old, but the laboratory I was working was up in Stockholm. I went up to Stockholm and started making absorption panels.

Nebeker:

Is that something you designed?

Brüel:

We designed everything with it. We have this tube method, and I was very keen on using standing wave tubes. The transfer you get from standing wave tubes is only perpendicular absorption, you can get acoustic impedance this way. One other trick is to find out what happens when the wave is coming in at other angles, and another thing is to find out how much the absorption changes when you are split the material. You know they can absorb some energy from the sides too.

Nebeker:

Were the panels you designed produced?

Brüel:

Yes, all of them and later on in Finland too. It was a big business for the company there. Then the people from Chalmers University saw this work and I did some work there.

University of Gothenberg, acoustic lab

Brüel:

The University asked me if I would move to Gothenburg, and make an acoustic lab there. Which I did in the beginning of ’44, which was before the war was over.

Nebeker:

They gave you a position at the university?

Brüel:

Yes. That was the base for Torkemann’s laboratory. As assistant I had Uno Ingardt. He is now on pension but he ended up as a very famous acoustics professor at MIT.

I stayed there until about ’48, but while in Gothenburg we worked mainly on building the laboratory, building of sound insulation, sound transmission, also we did some concert halls.

Nebeker:

What instruments were you principally using in that work?

Brüel:

I used a deconstructor. We made this very famous dynamical level recorder which was the first to work. The dynamic level recorder is an instrument that could measure reverberation time. Another way of explaining it is to say it gives an exponential function of everything and turns that into a log function with a straight line. As you know, every exponential function, if you take a log of that, it starts out going right, and in a good acoustic everything should be an exponential function of when the sound dies out.

If it is not on a real exponential curve it is difficult to see if it is exponential, but if is a straight line it is easy. Therefore, it is very important that you get an instrument that can take the log of the curve.

Nebeker:

While at Gothenburg, were you making things for your own use?

Brüel:

Yes, but of course we used it in the laboratory.

Nebeker:

But, did you try to go into production of that instrument.

Brüel:

No, because we had previously decided to start production of the instruments in my company, but Mr. Kjær stayed in Denmark.

Brüel & Kjær; WWII-era travels to Denmark

Nebeker:

Did you decide at an early stage that you wanted to work with Mr. Kjær?

Brüel:

Yes, we were good friends and he was interested in technical guides too.

Nebeker:

You intended to go into business with him?

Brüel:

Yes. But we waited because we had different interests. I wanted it to work on acoustic measures and he want to work on electrical.

Nebeker:

Also, he stayed in Denmark, correct?

Brüel:

Yes, and he got some job in radio factition.

Nebeker:

But you kept in touch with him and still had this intention?

Brüel:

Yes, we kept in touch. I had these false papers that I used to fly back from time to time. After some time the Germans canceled that, so I could not go back.

Nebeker:

Wasn’t that risky, going back into Denmark?

Brüel:

I had to do it. Niels Bohr, he fled from Denmark and needed to get some communications back there. Also, I was writing this doctor’s thesis to take to the University. Because the manuscript was a big and complicated thing, I could hide Bohr’s papers in it.

Nebeker:

Was Mr. Kjær actually in business at that point?

Brüel:

Yes, and I was too, in a way, because I could travel both to Finland and Norway, from Sweden, and so we could, we could sell some equipment in those countries.

Nebeker:

Even during the war you had sold some equipment?

Brüel:

Yes. The problem was getting the material to make it. If you refused to work for the Germans then you don’t get any materials. Luckily, I had a good friend who was trying to make so much trouble for the Germans. Once I told him we did not have copper wires and were using aluminum wires, instead of copper, so he said, well I think I can get you some copper wires. He said that the German have a thick communication cable from Copenhagen to Berlin, and that was under water in the [unintelligible] boats. We used that and Hitler couldn’t speak with the Germans for a time.

Nebeker:

How did you get the copper wire?

Brüel:

We went out to the seas, dove in, and picked it up.

Post-war business

Nebeker:

What about after the war?

Brüel:

After the war, I stayed in Gothenburg but only for three days a week, the rest of the time I spent in Denmark. I did this for more than two years.

Nebeker:

Did you have a formal business arrangement with Mr. Kjær at that time?

Brüel:

Yes, we had started the company in ‘42 but we didn’t want to work for Germans. After the war we picked up very big orders, but had to rebuild our laboratory because the building had been blown up.

We got orders on shoe-port meters, and differential bridges, oscillators, analyzers, and things like that, once the war was over. And we got prepayment for it.

Nebeker:

How did you get that order?

Brüel:

Everyone knows each other here. We know the Philips people very well, the Danish Philips people, and they have good connections with the other company there. Mr. Kjær, he had been with one of the radio manufacturers at Philips during the war.

That was the line. He worked for Philips during the war, and then when we officially started with the company, the Philips said you couldn’t have two positions. You will either you have to work for us, and give up your position. He said Yes, I will.

[End of tape one, side one.]

Acoustics for building planned by Hitler

Brüel:

I think I should tell you that, a funny story there. Hitler had decided, somewhere beginning of ‘41, that he wanted to make a tremendous building. The was it should be ten times bigger than any other room in this world, to be what he called Siegesmonument, or something like that.

Nebeker:

This was to be in Berlin?

Brüel:

Yes. They soon realized that they needed to work on the acoustics of the place. The hope was to ask Professor Meyer in Göttingen what should be done, but he was not invited because he really did not like the Germans. Therefore, they asked the architects what they should do about the reverberations because they could not understand a word Hitler was saying in the room. It was suggested that they should remove the marbles and rockerwood on all the walls, then there might be a chance.

Of course they didn’t like that, and then Mr. Dey who was the minister of the whole building made a suggestion. He had heard that this Mr. Olsen could manage acoustic, so they decided to contact him. Olsen said that he could manage the whole thing by using lead as a buffer.

They told Professor Meyer that they found a solution in a fellow in Denmark who could manage the whole thing by putting lead in there. Professor Meyer of course didn’t believe that. Olsen’s proof came in the form of a made church here, called [unintelligible] Kirche. It was made of brick inside. And the brick construction had wonderful acoustics because it absorbs some of the sound and then spreads it out because brick is a natural. Olsen proved his theory with that church and many other things.

Professor Meyer asked Professor P.O. Pedersen if he could go and make some measurements in this [unintelligible], and P.O. Pedersen said absolute not. Pedersen did not want to do anything with the Germans at all, so he refused to allow it. Professor Meyer then wanted to just send some people up there and do measurement, but he couldn’t because he did not have the instruments. Meyers ask Pedersen to lend him his instruments, and fearing Nazi retaliation, he said yes.

In the end Professor Meyer sent a truck up, full of instruments and two people, to take the measurements.

Nebeker:

Did you go with them?

Brüel:

No, I did not, we just supplied them with the instruments.

Brüel & Kjær instrument production; level recorder

Nebeker:

What you are explaining is that the instrument company had this very large order during the war?

Brüel:

Yes, and we continued getting it during the war. Then I made up a level recorder, and Mr. Kjær refined the analyzer, so we had a really good instrument. It was one of a kind. Also making level recorders at the time was a very good acoustic fellow named Leo Beranek.

Nebeker:

Who was he?

Brüel:

There was a guy who did his doctoral thesis at MIT, named Montague, he also knew Beranek. They did some work, along with Bolt on how the waves move inside a room. This was very useful because if you could solve the wave equation inside a room, then you could put the similar conditions on an acoustical piece of it in the walls.

Due to the work they did I was in correspondence with these people, and knew all that they had written. Beranek saw the potential in this level recorder, and already in 1950, we were selling them in the States.

Nebeker:

When did you stop at Gothenburg?

Brüel:

In ‘44, I got what we call a Dozentstipendium, that was the money that the government paid to university teachers, but limited to three years. So, I got this sort of stipend for making the acoustic laboratory.

Nebeker:

Was it in that three-year period that you worked full time with the instrument company?

Brüel:

Yes, and that went very well, especially the level recorder which sold like hotcakes.

Nebeker:

How did you organize production?

Brüel:

We had 200 people in the company, and we made practically everything ourselves. Very little was done outside the company.

Nebeker:

How was the business organized?

Brüel:

Everyone was taking care of everything. I was mainly in the laboratory and the application of instruments, and that was connected with the sales. As a result, I did the traveling. Kjær didn’t like to travel, he stayed home and he took care of the money and the organization. He was a brilliant technical person, and always had the final word in the laboratory.

Nebeker:

What about business people?

Brüel:

We did not use business people. We only had technically skilled people.

Nebeker:

But what about the payroll, personnel, and things like that?

Brüel:

There was one man, and a few girls to handle that.

Nebeker:

And this was something you oversaw?

Brüel:

No, that was mainly Vigor who looked into that. He was a very ordered person.

Nebeker:

You were also involved, however, in the development of the products.

Brüel:

That was my main interest. Mr. Kjær and I very often didn’t agree, but we agreed very early on. We had lined many things up, standard screws, and the how the cabinets should be, and colors, so we did not have any discussion of that. We actually were one of the first companies to use a design man. In that day we called them a BK rules.

Nebeker:

A what?

Brüel:

A person who decides how the nuts should be, how big the nut should be, what color, and was level you should put on the front plate.

Nebeker:

Was the idea to simplify the subsequent work?

Brüel:

No. We wanted it naturlich and for it to look nice. We wanted several instruments to stay side by side and look the same.

Nebeker:

At some point there was an effort, I know in the United States at least, to have standard sizes for instruments. Is that what happened to you?

Brüel:

Yes. There were the international standards we had to follow, but the color we could choose ourselves, the corners, and where the screws should be we could decide.

Nebeker:

Are you saying that you set up the rules for the “the company look.”

Brüel:

Yes, and that was made before we really started. When you have fixed rules like that, how instruments should be and look, then you cut out a lot of discussions later on. We saw this happen to many other companies. But here, we got rid of all of that because we had a rule-no discussion! With the standardization of part, you have the same components set up, and that keeps your stock down.

Nebeker:

What about marketing, in the widest sense? I mean, how do you get the word out to people about your company?

Brüel:

The marketing was very interesting. We wrote articles about solving the problem with those instruments. We went to universities, I was traveling all over the world; we had plenty of advertising.

Nebeker:

Did you tap into other fields?

Brüel:

Yes, and we worked with mailing services, where we obtained a list of customers. Also, we worked with car manufacturers in Detroit and so on. There were also the airplane companies like Boeing.

Nebeker:

What about advertising the acoustic engineering?

Brüel:

We did that, and we are very fond of advertising there, because German Acoustical Society was very well off at that time. We eventually persuaded them to make advertising.

Nebeker:

They didn’t do it before?

Brüel:

No, but they did and we used them for several years. Interestingly, it was not very effective in the United States because only professors read it.

Nebeker:

Did they buy instruments?

Brüel:

Yes, they do now, but at that time it was limited, they simply made their own. The real catch was when we went into Russia, we did that very early around 1950, we went to China a little later. In China we got our best advertising from the ads in the German Acoustical Society, because the Russian were buying a few copies of that and then reprinting it. The copies were sent all over Russia and Siberia.

Nebeker:

You had early sales to the Soviet Union and China?

Brüel:

Yes to Soviet Union in ’50 and China in ‘53. The China sale was fun because Americans said don’t go in there, it’s a terrible place. As a result, most of the companies backed out.

We sent a small delegation, about ten people, to China. We were the first European people that came into China. The Chinese didn’t know what to do with us, and we didn’t know what to do with them . We had planned this for six weeks and after three days we had absolutely nothing more to talk about.

Nebeker:

Were these other technical companies?

Brüel:

Yes. There was Danfoss there was [unintelligible], and there was about ten. Danfoss was there, Grundfos was there, Gram was there for the cooling machinery. I think I was the only electronic company.

Nebeker:

After three days there was nothing else to say?

Brüel:

Yes, but we could not leave because we would have lost face. The Chinese didn’t know what to do so they put us on a train and we traveled around China. Still we had a lot of time left so we went to the university and took numerous pictures. I also gave a lecture in acoustics at the university.

Nebeker:

Did you deliver in English?

Brüel:

Yes. I gave the lecture in English and Professor Ma from MIT who was there, translated. Every lecture took about five to six hours.

Nebeker:

Did this generate a lot of business?

Brüel:

Yes.

Condenser microphones; noiseless filmstrip

Nebeker:

You mentioned a couple of the important early products. Could you tell me what the most important products were after the war?

Brüel:

- Audio File

- MP3 Audio

(304 - bruel - clip 2.mp3)

The level recorder was absolutely most important, and after that, we bought condenser microphones from a Danish company called Autofon here. The same people who made this also founded the noiseless filmstrip.

With the first film strip, when it was black and white, you could talk on the black part. That of course gave you an image and a little dust on the white part would make sounds. What these people did was turning it around, so that the texture of the sound was black and the white was not able to produce sound. That way, the dust on the black white wouldn’t make noise. It was a very simple idea.

They got a patent on it and made a huge company out of that. Then Western Electric brought that patent from them later on and made a huge business out of it. By the way, when you were talking about Marconi making a big business out of the spark transmitters, and then when Poulsen came in the arc transmitter, P.O. Pedersen was there when the first transmission of talk, or music instruments, over radio, was made. It was made from a radio station that is up here. The receiver was down the brewery at Tuborg.

P.O. Pedersen was standing by when the Poulsen people were trying to talk in the Reis microphone and modulate the real power going out to the antenna. It’s funny to think that that was the first communication, besides sparks, in the whole world.

Nebeker:

What about the post war products you produced?

Brüel:

Yes. Next were those condenser microphones we bought. Western Electric, made beautiful microphones, the 640 AA, and this company Autofon did so as well. They were all made with the diaphragm clamped in between an outer ring and the main housing of it, and we couldn’t really understand why it was gaining one or two db a year in sensitivity. We finally found out that if you had a paper to it and moved your hand over the crown, the paper would be visible coming out. Very simple again. The diaphragm had to be under stress all the time, and its clamp between two pieces of metal. Then when you put your hand on one, or the top part may be slightly hotter than the other one, it would cause a change. If the two pieces of metal have different temperatures, they will automatically move, maybe not just one second but two seconds.

We solved this already. Instead of having to clamp it in, which you had to have it welded, or glued, or soldered. Then when we wanted to make one very light, nobody could roll the material out, except in very soft aluminum. That, however was not very good because you couldn’t roll it out without holes in it. Consequently, we plated the diaphragm, and due to that we could control it just by having to tighten the clamps.

Nebeker:

What are you plating and what did you start with?

Brüel:

We started with a foil. It was very simple, you just put some things in it that doesn’t make it difficult for the current to go through it. We washed such a metal plate with that and got it to the thickness we wanted. Then we tuned it up and took the foil off of it.

Then when we started with the microphone. We said instead of doing that we could take the whole microphone put some of the housing on it, and then put some wax in it. With conducting material on top, we plated the microphone the whole way around, even outside the housing. Then you have a crystalline connection.

Later on we found out that if you press this brass ring, which we did in any case, you could just solder up there and then you have the same connection that what we do today.

Nebeker:

When did you develop that microphone?

Brüel:

That must have been the early ‘60s.

Nebeker:

Was a very successful product?

Brüel:

Yes, a very successful product. But again, maybe I told you, in the standards business we had a philosophy before we started. We said we would not start on any project, which we not can sell. I think I said fifty and Vigor said 100, and then we compromised at seventy-five. Therefore, if we could not sell seventy-five we wouldn’t touch it.