Loudspeakers

A loudspeaker converts amplified electric signals from radios, televisions, and stereo systems into sound that you can hear. In many ways, a loudspeaker is the opposite of a microphone, which converts sound into an electric signal. In the most common type of loudspeaker, an electric signal passes through a small coil of wire, creating a rapidly varying, powerful magnetic field around the coil. Nearby is magnet, and the field around the coil and the field around the magnet begin to interact. The coil is mounted on a thin, flexible paper or plastic done, which allows it to move back and forth rapidly. The vibrating cone causes vibrations in the surrounding air, which our ears can hear as sound.

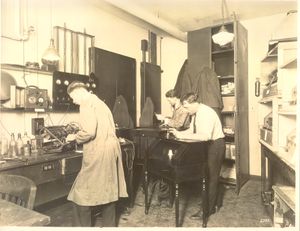

Modern electric loudspeakers had their origins in telephone and radio technology.

Of course we do not need loud sounds for the telephone, and early radio relied completely on earphones, so the name “loudspeaker” was not used at first. The electric devices used to create sound in the telephone and in radio earphones were called “reproducers” or “receivers.” Occasionally in the 1880s and 1890s, inventors would think up ways to use the telephone for a large audience. Some simply attached a large horn to an ordinary telephone receiver in an attempt to make a “loudspeaking telephone.” That’s where the term loudspeaker comes from. But these loudspeaking telephones could not produce much loud sound.

Until the invention of electronic amplifiers, a truly loud speaker was not really possible, nor was there much need for an electric loudspeaker. This changed when Bell Labs introduced the first electronic vacuum tube amplifier in 1916. The first commercial electric loudspeaker, introduced in 1924, was based on a “beefed up” version of some of the early telephone inventions of Thomas Watson and the Siemens company in Germany in the 1880s. This loudspeaker used an electromagnet to drive a large flexible paper cone, which reproduced the original sound as it rapidly vibrated under the influence of the amplified signal.

This kind of speaker was fine for public address systems, which were first offered in 1921, but the sound quality was not good enough for motion pictures. It wasn’t until talking motion pictures became a reality in the late 1920s that speakers with better sound quality and louder sound capability were introduced.

In the meantime, radio spawned another branch of loudspeaker technology. Radio was a technology for the home and large, expensive loudspeakers invented for public address and movie purposes were not suitable. Brunswick Balke Collender Company introduced the first all-electric home phonograph around 1924 in cooperation with RCA, General Electric, and Westinghouse. It was the first home phonograph to use what the company called a “dynamic” loudspeaker, which is similar to the kind still in use today.

Although loudspeakers have become more powerful, and their sound has steadily improved, most of them are not much different than the loudspeakers introduced in the early 1900s. One important exception is the “electrostatic” type of loudspeaker. In this type, instead of using an electromagnet to vibrate a paper cone, a sheet of metal or plastic is vibrated by a powerful field of static electricity. Some say that these speakers sound very good, so they are beloved by home audio enthusiasts. But they are very expensive and depend on extremely powerful amplifiers, so they are not suitable for car stereos, boomboxes, or the inexpensive home stereos that most people own.