Oral-History:Knud Holst

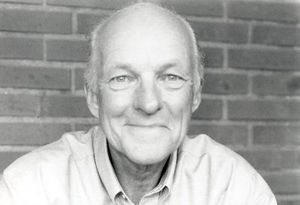

About Knud Holst

Born in 1928, Knud Holst trained as a radio technician, completed one year of military service, and studied engineering at the Aarhus Technicum. He began employment at Bang & Olufsen in 1952, working as a development engineer on aerial amplifiers for television and working on the company's second television model. In 1954, Holst began employment with the Radio Technicum Research Laboratory, where he worked on television sets and transistor radios. Holst describes this laboratory's function in Denmark's radio industry and details the development challenges on his projects there. Returning to Bang & Olufsen in 1956, Holst worked on TV set development for the company while working privately with other Bang & Olufsen engineers to develop a transistor receiver. This privately developed technology influenced later Bang & Olufsen radio products.

From 1961 through 1972, Holst served as head of electronic development and then head of development at Bang & Olufsen, and he details projects he oversaw during this period. The interview covers Holst's work on transistor radios and stereo radios for Bang & Olufsen. He describes the influences of technology and design in development of the transistorized mains-operated receiver, and he analyzes the roles of the outside designers Bang & Olufsen hired, including Jacob Jensen. Engineers and designers collaborated on product development, working with components and materials.

In his analysis of the 1950s and 1960s, Holst details radio and television set design, marketing, and sales. He describes collaborations between Bang & Olufsen engineers and their component suppliers, including the educational roles performed by Philips and RCA. Holst describes the special relationship between Philips and Bang & Olufsen, detailing the support that Philips provided for testing of his transistor receiver.

Holst describes the production challenges Bang & Olufsen faced in the 1970s, after the company's growth in the 1960s. In the late 1970s, Holst participated in intelligent product research as along-term corporate planning strategy. This work led to Bang & Olufsen's development contract with Jutland Telephone and its expansion into concentrator production.

The interview concludes with Holst's thoughts on European business and on the role of Bang & Olufsen in the Danish economy.

The oral histories of Jens Bang, Keld Harder, Jacob Jensen, and Jørgen Palshøj also cover the history of Bang & Olufsen.

About the Interview

KNUD HOLST: An Interview Conducted by Frederik Nebeker, IEEE History Center, 22 July 1996

Interview # 307 for the IEEE History Center, The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc.

Copyright Statement

This manuscript is being made available for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the IEEE History Center. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of IEEE History Center.

Request for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the IEEE History Center Oral History Program, IEEE History Center, 445 Hoes Lane, Piscataway, NJ 08854 USA or ieee-history@ieee.org. It should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user.

It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows:

Knud Holst, an oral history conducted in 1996 by Frederik Nebeker, IEEE History Center, Piscataway, NJ, USA.

Interview

Interview: Knud Holst

Interviewer: Frederik Nebeker

Place: Struer, Denmark

Date: 22 July 1996

Childhood, family, and education

Nebeker:

I wonder if I could first ask you where and when you were born.

Holst:

I was born on the 25th of July, in 1928.

Nebeker:

1928. Where?

Holst:

In a small town called Gitstelt, 30 kilometers north of Viborg.

Nebeker:

Okay, so in North Jutland.

Holst:

No. Himmerland is it called.

Nebeker:

Okay, Himmerland. Can you tell me something about your family?

Holst:

Yes I can. My father sold equipment for gentlemen, that is, he was a haberdasher.

Nebeker:

Yes, clothing sales.

Holst:

Clothing. Haberdasher, is that right?

Nebeker:

That’s right, but it’s old fashioned.

Holst:

Yes. And his father was a teacher, in a small school. I don’t know exactly what he taught. My mother was educated, not well educated, but an open-minded lady who had attended high school. It was what we call high school in Denmark, not your high school.

Nebeker:

Gymnasium?

Holst:

No, no, not that either, but an open educational format you don’t really find in many other countries.

Nebeker:

Okay.

Holst:

And her father was a carpenter. He had a lot of technical skill in his day. When he was a young man, he could understand all types of equipment that came within his reach. That’s a difference from today; not many of us would understand totally what our PC does. But he could understand some things in those days. I think I got a lot of technical feeling from him.

Nebeker:

I see, you were together with him sometimes?

Holst:

Yes. Early, I decided that I would try to be educated as a radio technician. I got an apprenticeship, and was educated as a radio technician, in 1948. I went for one year of military service, and then I took an engineering education in Aarhus.

Aarhus Technicum

Nebeker:

At the Technicum?

Holst:

Yes. And then right after that, I started here at Bang and Olufsen in 1952.

Nebeker:

I see. So when you were a youngster, radio already interested you?

Holst:

Yes.

Nebeker:

You decided that was what you wanted to do?

Holst:

Yes.

Nebeker:

The path that you followed, that’s not the usual path, is it, for going to the Technicum?

Holst:

Yes, it is.

Nebeker:

It is?

Holst:

One of the conditions was that you should have had an education as a craftsman.

Nebeker:

I see, so you had to first be apprenticed to a craftsman?

Holst:

Yes.

Nebeker:

I do know the reputation of the Technicum for producing more practical engineers as opposed to the theoretical engineers of the technical university in Copenhagen.

Holst:

Around the time when I came to Bang and Olufsen, we brought a lot of engineers from Aarhus Technicum, to such a degree that the headmaster of the Technicum said that he had the feeling that he was one of the suppliers to Bang and Olufsen! [laughter]

Nebeker:

Well, of course, both founders of the company came from that school.

Holst:

And you’ll find that many of the industries here in Jutland were founded by people educated at Aarhus.

Nebeker:

And I know a lot of people who worked at Bang and Olufsen left to establish their own companies. What, can you briefly describe the education you got at the Technicum?

Holst:

I was all over until the third year, when they educated electronic engineers.

Nebeker:

So the first two years it’s a general course?

Holst:

No, no. [laughter] That was not what I meant. The education of electronic, electric, and radio engineers started two years before I arrived.

Nebeker:

I see, it had just started there.

Holst:

Yes. So it was a rather new direction. We were educated to a high degree together with the electrical engineers. I have been told that one of the main applications of copper is for the firing place in [unintelligible] and I was taught how to make big, heavy electrical transformers.

Nebeker:

I see.

Holst:

But after all, we had a very enthusiastic teacher who taught us a lot of the radio techniques as it was in those days. I have a feeling, we would, as to practical use of what we learned, we got a really good education.

Nebeker:

Who was that teacher?

Holst:

It was Wolf Jakobsen. He’s still alive. He was headmaster of Aarhus Technicum for many years. He retired I guess, ten or twelve years ago, and I have had a lot of cooperation with him. I have been president of the board of Aarhus Technicum for twenty-five years, so I have had a lot of cooperation with Wolf Jakobsen. Yes. He’s still alive, and still very creative, yes.

Nebeker:

I see. What year was it then, that you completed your degree?

Holst:

In 1952.

Bang & Olufsen, aerial amplifier development

Nebeker:

In 1952. And you immediately got a position at Bang and Olufsen?

Holst:

Yes. I did.

Nebeker:

Had you decided that was what you wanted to do?

Holst:

Yes.

Nebeker:

There was no doubt in your mind. [laughter]

Holst:

No, it was decided before I started studying in Aarhus.

Nebeker:

Right.

Holst:

I would try there.

Nebeker:

What was your initial assignment with the company?

Holst:

It was as a development engineer. I started making aerial amplifiers for television. Television signals in Denmark had just started. In many many places, the signals were very weak. We had to place a preamplifier right at the antenna site.

Nebeker:

I know I took note that regular broadcasting began in 1951 in Denmark.

Holst:

Yes, initially in the Copenhagen area. I have the prototype here in the basement. It was the first prototype that I made of such an amplifier.

Nebeker:

Is that right? I see. So for a long time, there were not enough transmitters that people could easily receive the broadcast, and so, was it standard for antennas to be equipped with an antenna amplifier?

Holst:

In many cases, yes.

Nebeker:

And was that a product that Bang and Olufsen developed and sold? In large numbers?

Holst:

Not in large numbers, but, under Danish conditions, yes, a lot of them.

Nebeker:

Outside of Denmark at all?

Holst:

No, we had absolutely no exports whatsoever in those days.

Nebeker:

It sounds like that was a good assignment, to be with the development team.

Holst:

Yes. It wasn’t a team in those days. I did it myself.

Nebeker:

Is that right?

Holst:

Yes. In those days, the word product had not been found out.

Nebeker:

So you were just told that you alone were going to design that amplifier?

Holst:

Yes. They said, "You make that aerial amplifier," so I did it.

Nebeker:

I see. And was it your design that was put into production?

Holst:

Yes.

Nebeker:

Okay.

Holst:

As a career engineer, you were allowed to do such things. If you could.

Nebeker:

How long was, was that product manufactured?

Holst:

I guess it took more than half a year to get it from my idea to production.

Nebeker:

I see.

Holst:

But that’s guesswork.

Bang & Olufsen television receiver

Nebeker:

Okay. Do you remember your next assignment?

Holst:

Yes, it was the number two television receiver that was made in the Bang and Olufsen company.

Nebeker:

You mean their second, their very second receiver?

Holst:

The second type of receiver, yes. There were, I guess were three men making substitutes also.

Nebeker:

I see, it seems to me, yes, that the first Bang and Olufsen television was introduced in ‘52, and it was the second model that you worked on?

Holst:

Yes.

Nebeker:

I see. Could I first ask, how large this development group was, how many engineers were there?

Holst:

Three, I guess three engineers.

Nebeker:

Is that all?

Holst:

Yes.

Nebeker:

I see.

Holst:

In those days, you have to understand that all of the details in the working methods of a TV set.

Nebeker:

Uh-huh.

Holst:

There were thirteen tubes or so in a black and white receiver, and you could in your head understand, how each one worked.

Nebeker:

Okay.

Holst:

The deflection coil, the picture tube, [unintelligible], all that.

Nebeker:

I can see that if it’s a small group of engineers, and I know the company is producing many products, you have to be versatile yourself.

Holst:

When I started in ‘52, there were around twenty companies in Denmark making radio receivers, and there were thirteen that developed in such a way that they could make TV sets.

Nebeker:

I see.

Holst:

Out of those thirteen, three came so far that they could make a color TV set. Only one of those three survived.

Nebeker:

I know that the late ‘50s was the big period for sales of television sets in Denmark. When was this second television set marketed?

Holst:

It must have been 1954. Bang and Olufsen had financial difficulties in ‘54. I left the company in ‘54, that wasn’t exactly because they had those difficulties, but it was a coincidence, because I wanted to get some further education.

Radio Technicum Research Laboratory

Holst:

In those days there was something called the Radio Technicum Research Laboratory. It was more or less an [unintelligible] from this patent society.

Nebeker:

Could you tell me just a bit about that patent society?

Holst:

Yes. This was a society where all the Danish radio manufacturers paid a yearly fee, and then it was also supported by the Danish Technical High School in Copenhagen, and there was I guess only one man employed. He of course ran into some technical problems, and to investigate them this radio technical research laboratory was created around ‘50. Perhaps ‘48.

Nebeker:

I see.

Holst:

Under the leadership of a man called Georg Vruun.

Nebeker:

Was it in Copenhagen?

Holst:

That was in Copenhagen, and they were placed in the Danish Technical High School. And employed there were the biggest, I guess, seven or eight engineers, and a couple of technicians.

Nebeker:

I see.

Holst:

I saw a lot of that, I had a chance to be employed in this laboratory for two years and a half, from early ‘54 to late ‘56.

Nebeker:

I see. Did you, you applied for a position?

Holst:

Yes. With the recommendation from Bang and Olufsen, yes.

Nebeker:

I see. They weren’t angry that you were leaving?

Holst:

No because, they had financial difficulties, so there weren’t problems.

Nebeker:

I see.

Holst:

I left the company after we had put the TV sets into production, and started with Georg Vruun, in Copenhagen. And there I also mostly made TV sets in the beginning, but later on I made, I guess it was the second operating transistor radio in Denmark.

Nebeker:

Could I just ask you a bit more about the purpose of this laboratory? You said initially it was to settle technical questions that came up in connection with patents.

Holst:

Yes.

Nebeker:

Did that continue to be the-

Holst:

No, it worked also in another direction, and that was the principle research organization for the Danish radio industry, and meaning that the first TV sets, the ones that Bang and Olufsen made in ‘51, was directly developed according to prescription that was made in radio research laboratory.

Nebeker:

I see, so they acted as sort of the common research laboratory for the industry.

Holst:

Yes. And many of the companies that made receivers, directly followed the instructions that were sent out from the laboratory.

Nebeker:

Did the Radio Technical Laboratory hold the patents that they then shared with the members of the society?

Holst:

Yes.

Nebeker:

So you worked first on television there?

Holst:

First on television, yes, and then I was put on this development of a very very early transistor receiver.

Nebeker:

What year was that, can you recall?

Holst:

Yes, that must have been ‘56.

Nebeker:

Yes.

Holst:

I still remember when we should present the set for the members, for the members of this laboratory, and the day before, I had made some experiment with it, so that it didn’t operate properly. And then Georg Vruun came and he looked over my shoulder and he saw that it didn’t operate and I thought, I got very very nervous, but on the day when it should be presented of course it operated. [laughter]

Nebeker:

Were you working with others on this design effort? The transistor radio?

Holst:

No. That was-

Nebeker:

That was your own design?

Holst:

Yes, yes.

Nebeker:

Yes. How did you learn about transistors?

Holst:

How did I learn about them?

Nebeker:

Yes. Was that through the literature, the published literature?

Holst:

That was through the literature. And also Georg Vruun, he made many designs himself. He was, he had a year of, he worked in [unintelligible] laboratory, in a year or two, around that time when he was in Radio Technical Laboratory, and he, he knew a lot about transistors, and could tell a lot about transistors, so we got a lot of ideas about what a transistor was.

Nebeker:

Okay. Were there good suppliers at the time, could you purchase-?

Holst:

No, no, they put it …

You should take your hat in your hand and ask politely to be able to buy transistors.

Nebeker:

I see.

Holst:

Yes.

Nebeker:

What was particularly challenging about that design? I imagine you can’t simply take, you know, a radio receiver design, of the tube era, and translate-

Holst:

It was quite a new way of thinking. When you came from tubes, with high voltages on the anodes, normally had 180 volts or so, as the anode voltage, and you could really feel it with your fingers if you touch the radio or the power supply in such a, in such a set. And all the hum problems, with the heating elements, and using transistors you would forget all of that. We also thought that you could forget all about heating problems, that you would [unintelligible] on the bigger ones.

Nebeker:

I see.

Holst:

Then of course the impedance levels are so different, so that you have to-

Nebeker:

Redesign quite a bit.

Holst:

Yes, learn to think in quite another way. It was also such a small thing as using the negative as, as the anode supply, not anode supply but collector supply. That’s quite another way of thinking than using the positive angle for, but you adjust to it. But I think you asked for the biggest difference, the biggest difference is the difference in the impedance levels, and, and that the impedances are not, are always complex.

Nebeker:

Oh. Yes. Did you have the theoretical training to work in a theoretical way with this design?

Holst:

Yes, yes. I got that.

Nebeker:

Yes. Was this a successful design?

Holst:

To such a degree that this report was used for people in Denmark who make-

Nebeker:

Oh, they followed this design? I see. That’s quite an achievement then to be designing for a large number of companies. Was it used also by Bang and Olufsen?

Bang & Olufsen TV set development, transistor receivers

Holst:

In a way yes. I came back to Bang and Olufsen in December-

Nebeker:

1956?

Holst:

Yes. And my first appointment was to make transistor receiver for Bang and Olufsen. No, that’s not right. I participated in normal development of TV sets. But we were ten engineers and technicians in the company, who were got the idea that we would make a transistor receiver for ourselves, so we developed a transistor receiver in our spare time. Of course, I developed it and the mechanic, the mechanics made, the mechanical people make the mechanics, the design people make the design, and so on, and so on, and so ten of us got a privately made transistor here. You asked just a moment ago about how to, it was easy to get transistors. And we had to use all the force of the Bang and Olufsen purchasing department to be allowed to buy ten sets of transistors, ten kits of transistors for those private [unintelligible]. And really to squeeze

Nebeker:

Oh. When you say private, thank you, when you say a private development, I don’t understand. You mean this was not a company product?

Holst:

Right. It was, it was, I used my experiences from the radio technical laboratory to make the electrical circuits, and the some of my colleagues made the handwork, making the circuit boards, and-

Nebeker:

You’re doing this on your own time?

Holst:

Yes, yes.

Nebeker:

I see.

Holst:

We wanted to have a transistor radio.

Nebeker:

You mean purely for personal use?

Holst:

Yes.

Nebeker:

You didn’t think of forming a company and manufacturing-

Holst:

No. I have a sample of it in the basement.

Nebeker:

I see. And it worked?

Holst:

Last time I had batteries in it, it worked, yes. And that’s three years ago.

Nebeker:

That’s very impressive. What year was that finished?

Holst:

It must have been 1957. And shortly after that, we started company development of a transistor receiver.

Nebeker:

Was that going further from the design that you had already made?

Holst:

Yes, yes. Yes, yes.

Nebeker:

Okay. Were other people working with you on that design? At Bang and Olufsen?

Holst:

Yes, yes, yes, yes. Mechanical people and, yes, we were a small group making this receiver.

Design challenges in television receiver design

Nebeker:

I see. And before we follow that, I wanted to ask you, since you worked both in Copenhagen, and back here, on television receiver design. What were the big challenges for the design engineers then?

Holst:

Sensitivity. Because the coverage was not very good. Sensitivity was one of the problems, and then hum. Meaning that, especially hum in the light, yes, in, you could see hum-

Nebeker:

Bands?

Holst:

Bands coming down the screen, and that’s because, of course, we had a fifty cycle vertical, horizontal, a fifty cycle horizontal differentiator, yes, to get rid of hum, because then those bars would stand still on the screen, and not be seen. But in Denmark we had the problem because we have two mains working, the two power mains working, we have one on the eastern side, and one on the western side, and still today we have it, so that the network on the eastern side is synchronized to the [unintelligible] system, and on the other side it’s synchronized with the [unintelligible] system.

Nebeker:

I see.

Holst:

Those two systems are then connected through the protocol, that’s another question.

Nebeker:

- Audio File

- MP3 Audio

(307 - holst - clip 1.mp3)

I see, so there’re slightly different frequencies-?

Holst:

Slightly different, and in those days, there were differences, so that we could see those bars come down if we could not get rid of the hum, and the hum could come in from everywhere, especially from the heating system, because we had those series connected heaters, so that, because we’re not alternating current AC, we had DC in many places, therefore we had to, to make series connections in making the heat exchange. I remember one of the people in the Philips company, I shall tell you, how we got much of our technical background later on, we visited Philips very often and got , but one of the gentlemen there said, there’s a [unintelligible] for the lower places in the heating chain . [laughter]. Sound people would have sound tubes so that there would be no hum in the sound, and production people would have, and so on.

Nebeker:

I see. I don’t understand much of the circuit design, but you needed to have that because there were still many people receiving DC current?

Holst:

That had a DC power supply. And therefore, all of the radio, 99% of the radios and TV sets sold in Denmark in those days, were universal receivers-

Nebeker:

I see.

Holst:

Who could take both AC and DC. So we had 300 meter amps heater chains in the television sets. 200 meter amps in the radio sets. And that meant that some of the tubes would sit on the heater potential of 150 volts AC, universal to common, and then you get the hum induced in the whole tube, and also in the signals, out of the tube.

Nebeker:

Yes, yes. I see. So that was one type of problem, the sensitivity had to be very very high.

Holst:

Yes. And we had to fight that. Well, suppression of neighbor channels was one of the big items also.

Television sales, 1950s-1960s; Bang & Olufsen marketing

Nebeker:

And so this was for, you said even before you left Bang and Olufsen, you were working on their second television, and this was for later television? Was Bang and Olufsen very successful with its TVs in the late 1950s and early 1960s?

Holst:

Yes, you must say they were, they were successful, yes. We were successful, but almost everyone was successful, because if you had a TV set, you could sell it.

Nebeker:

I saw some interesting figures that I might put on the tape here, that I forgot now, but something like in 1954 there were just a few thousand television receivers in Denmark, and 25,056, and 583000 in 1961, so in the late 1950s and early 1960s, they became-

Holst:

Every TV set got sold.

Nebeker:

Yes. But then there was something of a dip in the market in the early 1960s, right, because maybe it saturated the home market. Was there some response to that by the company?

Holst:

I don’t remember the years exactly, but in Bang and Olufsen, as in, I guess in every company, there has been ups and downs, and then, Jens Bang will be able to remember when we had our downs, and I, I-

Nebeker:

I just wondered if maybe the development people were asked, you know, now we’ve got to produce a new model to create sales from people who already have a TV set.

Holst:

Strategy was not an issue in those days, and as a career tactic you would never discuss strategy as strategy. The sales people knew something about what the market expected, and we were, Bang and Olufsen was highly technically driven. So that when new technical possibilities came, then we started using them. And if that indicated that we should make a new model, we made a new model. We made a new model every year, almost every year of almost all our things, radios sets and TV sets.

Nebeker:

Was it really that regular? Every year a new model?

Holst:

A new model, yes. Not necessarily a new basic chassis, but a model that in many ways looked different, and also had the new technical achievements in it.

Components and suppliers; collaborations with Philips

Holst:

We, in those years, we got less and less of our technical background from radio technical research laboratory, and more and more from our suppliers. That meant that we traveled a lot. Before it was normal to make a flight, we took a car to Einthoven, and visit Philips for 8 days, in tightly scheduled program where we visit their central laboratories in Europe, CLB laboratories, and we went from speech to speech and discussion to discussion and learn all about the new possibilities that Philips can foresee. We did the same thing in Ulm-

Nebeker:

Also in what fields? Was that in television as well?

Holst:

Also in television. And took a visit also to Philips in Hamburg, we also visited the RCA laboratories in Zurich, so we tried to keep in touch and we compared to most of the other Danish manufacturers, we really triumphed.

Nebeker:

Now it’s because you’re buying tubes, the electron tubes and the picture tubes from Philips that they’re willing to share their latest knowledge?

Holst:

Yes. But we bought, of course a lot of components, in fact, Bang and Olufsen has not produced components, that’s alright, transformers, transformers and coils, but systems, capacitors, deflection units for TV, and front ends for TV, we made the front ends for our FM receivers ourselves, in fact, I made the front ends, yes, in many years I made them, of course the tubes, yes. That was the items that we bought.

Nebeker:

Yes. So that’s the, is that the usual sort of arrangement between these suppliers like Philips and Telefunken and the manufacturers in the different countries that they receive training of a sort?

Holst:

They gave us a lot of technical education, all of them. And if we had difficulties with one supplier, we just flirted with another, and in the arena, one would be so kind to us.

Nebeker:

It seems that there’s a long history, and a close connection between Philips and Bang and Olufsen.

Holst:

Yes, yes.

Nebeker:

You were much closer to Philips than to Telefunken and others?

Holst:

Yes. But, but of course we had connections to [unintelligible], and to RCA. We, sometimes we bought our color TV tubes from RCA, and only very very small amounts from [unintelligible].

Nebeker:

So with every component you would see, could we get it better from Philips, or better from elsewhere, is that right? Every single one you would consider.

Holst:

Yes, yes. At different systems, we bought them from many different suppliers. SDC? SDS? There was this internal supplier who, they have the know-how from RCA, we bought some transistors there. Sometimes there were shortages of transistors, sometimes they couldn’t make them, make the noise level sufficiently low, and then we had to go out on the market and find the best.

Nebeker:

Were you involved in this continual effort to find the best suppliers?

Holst:

Yes, yes. The person, [unintelligible] and I, we traveled a lot together, also to Japan. We didn’t buy much in Japan in my days, but we tried to follow the development also.

Nebeker:

I see. How do you explain the closer connection between Philips and Bang and Olufsen, and other suppliers that you named?

Holst:

As to Philips, I think, the Philips company of course, could, if they had wanted of course, they could have forced Bang and Olufsen to quit, because they were so big and so influential in Europe in those days, so they could have made life almost impossible for Bang and Olufsen.

Nebeker:

By aggressive marketing in Denmark?

Holst:

Yes, yes, yes. For instance. Or by having difficulties with one of the main components that their supply company produced. I do think that they had a company strategy saying that we get the most of the Danish market if we play good friends with Bang and Olufsen, let them have a certain part of the market, we supply the components, and we act as a good boss, that does not squeeze Bang and Olufsen out of the market. I, I’ve never heard them say anything like that, but-

Nebeker:

That’s the feeling you have.

Holst:

Yes, yes. All of us have the tight connection to it. And, what I had made first? Transistor receiver, that’s to go into production here, I asked for it, it was about to have 8 days stay in the CAB, the Center [unintelligible].

Nebeker:

CBA, maybe?

Holst:

CAB, Central Application Bureau in Einthoven, where with colleagues at Philips, we measured the whole set of them I had made, and-

Nebeker:

Do all testing on this receiver?

Holst:

Yes, yes. I guess it was the first time one of the customers was applied, was allowed to pay such a visit to-

Nebeker:

So they had all the test equipment, or some test equipment you didn’t have.

Holst:

Yes, and they had more experience working with transistors.

Nebeker:

I see. So you received unusual support in that.

Holst:

Yes, yes.

Nebeker:

Were they also marketing a transistor radio at that time?

Holst:

Yes, they were. But we, as technicians, we never had any discussions with Philips as to market, and marketing, and the Philips set supplying department. We never discussed with them. They were, quite another part of Philips who did it.

Interactions of marketing and development

Nebeker:

Was it the same way for you at Bang and Olufsen that your technical activities were in pretty much a separate realm from the marketing? In the sense that I mean-

Holst:

Yes and no. In many, of course the marketing people were influential as to what the new sets should look like, but the real core of the new idea was always made by the technical departments, and shown to the marketing people, and they could change the color, or make it a little higher or a little lower, until we really started working with designers, and then-

Nebeker:

I see, I see. So until then, you might be told by marketing people, we want a new model every year, or-

Holst:

No, no, we were not told, but it was in there that that was the way that we acted in Denmark.

Nebeker:

I see, so it was expected you’d produce a new model. Would they sometimes say, okay, well, there are new products, the transistor radio, for example. Is the initiative coming from the marketing people, we’ve got to have something out there on the market?

Holst:

Well, we started, I remember this first, yes, the first transistor receiver, we showed it to the marketing people, and well, that’s a new parallel radio. That was what they thought it was, just a new parallel radio. They dared to start two thousand pieces in production, and the first of the year, they had sold 8000. [laughter] Not a big number, but a big mistake.

Nebeker:

Now, was Bang and Olufsen already producing a small tube portable radio?

Holst:

No.

Nebeker:

So the transistor was the first real portable that they....

Holst:

Yes.

Nebeker:

And it sold much better than marketing expected?

Holst:

They couldn’t, they didn’t understand it, they didn’t find out what it really was.

Transistor radios

Nebeker:

Can you tell me a little bit about that, the history of the transistor radios in Bang and Olufsen, maybe Denmark more generally. You told me about the first design that you did, and then you said you worked on the design here for the Bang and Olufsen receiver, the transistor receiver. When was that first marketed, do you recall?

Holst:

Yes. 1959.

Nebeker:

How large was, this was one, they initially offered one transistor radio, or there were several models?

Holst:

This is probably only two. I have a picture of my eldest son, aged two years and playing with one of the early models, so therefore, and he was born in 1957, so [laughter]. Did you ask for a size?

Nebeker:

Yes, so it’s about four or five inches deep, and a foot or so wide, ten inches high, something like that. And they, did you then start offering different models of transistor radio?

Holst:

One new set a year. One year we made two sets, two different set, a small one and a bigger one. The small one was absolutely financially a fiasco. So.

Beomaster 900, stereo radio

Holst:

But then something new happened after 1964, and that was that Bang and Olufsen had in those days a cinema department.

Nebeker:

Cinema department, yes.

Holst:

They bought, I wasn’t connected to that, but they bought most of their real cinema equipment from Siemens, but amplifiers were made at Bang and Olufsen. And they made early in the 1960s a big amplifier with transistors. And we made, in the radio department, we made transistorized radios, so we connected such an amplifier, an [unintelligible] amplifier, and the [unintelligible] circuits from the radios, and made the first mains operated transistor radio in Denmark. Very very low, that was something, that was a new design, really a new design, because until then, radios were that high-

Nebeker:

Right, right. Is this the Beomaster 900?

Holst:

Yes.

[End of tape one, side a]

Holst:

High pressure [unintelligible], because in each end on the set, so that we got a real stereo effect. And this kind of a set was actually a new thing.

Nebeker:

Now these weren’t actually, there wasn’t stereo radio quite yet was there?

Holst:

Oh yes there was.

Nebeker:

I’ve forgotten when stereo FM came in.

Holst:

- Audio File

- MP3 Audio

(307_-_holst_-_clip_2.mp3)

I do think they were also stereo radios. But I wouldn’t be sure. But we could make this combination of the high frequency amps and the low frequency amplifiers that we had, and it looked very nice, it was, the sound was very very good, the sensitivity was acceptable, but it was so full of cross modulation, that you could feel each station at least twice. Normally people wouldn’t observe it, but if you had a little technical insight, you would observe that the transistors were not able to handle big voltages. So if you came near a powerful transmitter, then you would run into trouble. We had in those days an inspector, on behalf of the Danish P&T would inspect our radios for radiation, and he also had the job of buying receivers for prominent people, placed high in P&T. He called and said he would like to order ten pieces of that new set, because they were so marvelous, and the sound, and so on, so on. But the cross modulation is terrible, he told me, but after all, even if it was in some ways a lousy technical, he would order them. [laughter]

Nebeker:

I’m very interested in that, in that particular set, because it’s famous-

Holst:

Have you seen it?

Nebeker:

Yes, I have seen a model of it, or an example of it-

Holst:

Because I have also one of these in the basement.

Nebeker:

Okay, good. A number of things were special about it. You mentioned the speakers that were very good at the time, the fact that transistors are used rather than tubes, were there also tubes in there?

Holst:

No, no.

Nebeker:

No tubes.

Holst:

We placed the output and the power supply transistors on an aluminum back plate, so that we used the back plate as a heat sink.

Nebeker:

I see. And what most people notice of course is the design of that set. Now, except for this cross modulation problem, was it a very good design?

Holst:

Yes. Yes it was, but the front end transistors couldn’t stand high input voltages.

Nebeker:

Would it have been preferable to use tubes?

Holst:

Yes, in fact.

Nebeker:

Would if have been possible with that design?

Holst:

No, technically it would of course have been possible but it would have two different power supplies, one with anode voltage for tubes, and in practice it would have been impossible. You would run into hum problems once again.

Transistorized mains operated receiver; components and design

Nebeker:

Yes. Okay. How did that design come about?

Holst:

That was one of the first uses of an outside, real uses of an outside designer. What was his name.

Nebeker:

Let’s see, I know Henning Muldenhauer was one-

Holst:

Yes, that was one, Muldenhauer, yes.

Nebeker:

That was him?

Holst:

Yes.

Nebeker:

Yes.

Holst:

He also designed the pavilion we have here at the end of the swimming pool here.

Nebeker:

Is that right? [laughter] That’s something. Do you know about that design process? How it was run?

Holst:

No, no I didn’t participate in that, that was the manager of the technical department or the development department.

Nebeker:

I mean there must have been some recognition that using transistors rather than tubes made it practical to have a flatter set?

Holst:

Yes, yes. Yes, that’s right.

Nebeker:

So that was the, maybe the principal idea, that now we can have a very very flat shelf?

Holst:

The principal idea was to make transistorizing work. That was the principal idea.

Nebeker:

I certainly understand that for a portable receiver, but why is that, why was that regarded as an important for-

Holst:

Because we were technical freaks. [laughter] And if it was possible to make a transistorized mains operated receiver, then we would make it.

Nebeker:

I see. [laughter] Okay. And then somebody thought, ah, we have a design, I mean this is the-

Holst:

We have the possibility for this modern design, we make this modern design.

Nebeker:

Okay, and-

Holst:

You can hear that I was one of the technical people. It’s all refined.

Nebeker:

But what I’m trying to understand here and with other products is where the ideas are coming from, and how the process works. I mean, were you told okay, we want a very flat design here?

Holst:

No.

Nebeker:

No?

Holst:

No. We discussed that we could try if it was possible to combine those two parts, sets of equipment, and then we worked on it and out came-

Nebeker:

Something that was just flat. Flatter. [laughter] And that happened to be the right size for the speakers, or you made speakers that would-?

Holst:

We bought the smallest speakers that we could accept the sound quality of.

Nebeker:

With the thought that they’re going to be small enough to-?

Holst:

Yes. And to fulfill the goal the next year, we have to make a new one, and we thought that obviously, if that radio was a success, that the other radio must be a bigger success. We made it one inch lower, same-

Nebeker:

One centimeter lower?

Holst:

One inch.

Nebeker:

One inch lower.

Holst:

Yes, yes was one inch. And a little longer, and we thought that this must be a much bigger success. It was not. While in those days, the whole industry makes the same type of failure. Having two audio channels is much better than one audio channel, stereo is much better than mono, so four channels must be at least double than two. Failure.

Nebeker:

I see. Did this carry over to, obviously it did, the transistorization carried over to other products, the gramophones, and the, well this was, this was a, was this a combined-?

Holst:

No this was, this was only a-

Nebeker:

This was only a radio.

Holst:

Yes. But we used the chassis for a radio-gramophone. Not with much success, but we used it.

Nebeker:

Yes.

Holst:

And then of course we were forced to, well, the cooling conditions were best when the set was placed flat on the table, and we had to turn it so-

Nebeker:

Vertically?

Holst:

Vertically, yes, and the cooling conditions were degraded, with the result that it did not operate as well as it should.

Nebeker:

Why was that even thought about? Did somebody say, wouldn’t it be, would it be smart to have a vertical-?

Holst:

No, because it should fit into the end of one of those big radio-gramophones with the TV set here and -

Nebeker:

I see, I see, then it would be vertical.

Holst:

Yes, yes. And then the mechanics and the design people pressed us to accept that it could be placed upside down, and it didn’t work.

Nebeker:

And it didn’t—was it actually manufactured?

Holst:

Yes, yes, yes.

Nebeker:

I see.

Holst:

But, but, but with no good result.

Nebeker:

Technically with no good result.

Holst:

Yes, yes, yes.

Nebeker:

And it didn’t sell well either?

Holst:

I cannot say.

FM radios

Nebeker:

I see. You mentioned that you were involved with the first FM receiver, is that right, that Bang and Olufsen-

Holst:

No, the first FM receivers?

Nebeker:

Yes.

Holst:

No. That was Robert Messinger.

Nebeker:

Okay. What was your involvement with FM radios?

Holst:

Making front ends.

Nebeker:

Yes.

Holst:

I have developed, I cannot say, but 3 or 4 different front ends, partly with tubes and partly with transistors. And always fighting, fighting with radiation. Especially with tubes, it’s helps to prevent them, radiate as small transmitters.

Nebeker:

Were these for self-standing FM radios that Bang and Olufsen was producing?

Holst:

Yes.

Nebeker:

I noticed they offered a combined television FM receiver at one point early in the, somewhere in the 1960s there.

Holst:

Also, yes. And that, the first of them were tube FM receivers.

Outside designers at Bang & Olufsen; Jacob Jensen, aluminum

Nebeker:

What was this difference, you’ve explained some of it, that happened when the company started using outside designers? You said earlier that there might be some small changes that would be suggested by the marketing people after the-

Holst:

In many years the TV sets were designed by Muldenhauer, and of course TV sets are more or less, the design is, the frame of the design is in some way given. Whereas, the radio sets, and gramophones, there are more touch of freedom. And those, the smaller sets, the radio sets and gramophones, were designed by Jacob Jensen, whom you, have-

Nebeker:

I will see him tomorrow morning.

Holst:

You will see him tomorrow, yes. And he, one of his big essences that he, in one way or another he will learn how far he dare to press the technicians. If he wanted us to make a set somewhat smaller, he didn’t say you should make it 5 centimeters smaller, he found out it would be possible to press it one or two centimeters, let’s do that, and we did it, so that we always cooperated with him, and that we didn’t fight him. I put here from [unintelligible] companies that I had fights with, and therefore also sometimes cooperation with the designers [unintelligible], but with Jacob Jensen, we could discuss in a reasonable manner. And we gave him some possibilities that he knew really how to use, and well, we discussed it sometimes what it was that we could,. We could make, due to some of our story, Bang and Olufsen could make transformers, C-core transformers, or [unintelligible] transformers, and those transformers are much more power efficient than normal E I transformers. And we could make them lower, and that was one of the reasons why we could make this small radio, this was that we could use a type of power transformer. We gave Jacob Jensen this type of component to work with-

Nebeker:

You mean the actual component, so he’d-

Holst:

Yes, yes, no, but he, we, he could play on the Bang and Olufsen abilities to make transformers that were-

Nebeker:

So you gave him the dimensions of the transformers-

Holst:

Not exactly the dimensions, but the very concept of the c-core and the [unintelligible] transformer, was something that he could start from, and making smaller sets than any others could. And then Bang and Olufsen participated, I don’t know if he was a leading power in that, but he may have been, in using aluminum for the outer parts of the sets. And that really was a fight. Aluminum in those days was extruded to be used as window frames and so on, sitting high on a house, and when Bang and Olufsen asked to have an extruded object with a cross section the measure of .1 millimeter, they supplied, of course, a cross section of 1 millimeter. And when we asked them to make the surface free of pores, free of holes, so that we could grind it, and polish it, they supplied the normal quality full of holes, and so on, and we had to travel to them, and-

Nebeker:

Who was your supplier for this?

Holst:

There was one Norwegian, and one English, I don’t remember their names. But it was invited to make them supply aluminum parts that could be used for the Jacob Jensen designs.

Nebeker:

So this was a case of moving a step back, if the designer wants to make a certain effect, you can do that with aluminum, but you have to get the aluminum with the right properties in order to handle it the way you want.

Holst:

Yes, yes. So we gave him two, we gave Jacob Jensen two things to play with, the lower sets, because we could make the low transformers, and the aluminum surfaces, that no one else cared to make. I remember once the chief and I visited a company in Germany, that was supplying pushbuttons. And we had at that time trouble with the locks on the pushbuttons. And we asked, couldn’t you make those [unintelligible] locks. And then they said, in German, “We don’t make any of those parts.” Simply, they wouldn’t do it, because they knew that it would cause difficulties, so they didn’t make it.

Nebeker:

So you’re saying that it really was a difficult job to get -

Holst:

All, most aluminum parts made lot of difficulties.

Nebeker:

So, was Bang and Olufsen at the forefront of solving those problems?

Holst:

I don’t know, none of the other Danish radio manufacturers did anything near to what Bang and Olufsen did. And our suppliers didn’t like it, but they had to, and our competitors, really, the fact that not many of even of our competitors today will make such designs as Bang and Olufsen does.

Beomaster cabinet design

Nebeker:

The Beomaster 900, Jens Bang told me that one thing that was special about that, that may have existed on earlier sets, was that, of course in the old days, you had the radio chassis going into a cabinet. That had the cabinet. With that set, the chassis and the cabinet were in a sense one, that if you took the chassis out it would just, it would fall apart, is that-?

Holst:

That’s not right.

I could, I will show you. He has been a little too far from that set. No, it was a chassis put into a cabinet, as normal, yes. But what may have confused him is that we used the back plate as heat sink, and that was not normally used as.

Nebeker:

Okay, is that something that, that happened, this sort of combining of the chassis with the cabinet?

Holst:

That came later. That came later, and there you could argue that the cabinet, that’s, yes, in this set, I think, name was Beomaster 1000, the cabinet almost disappeared, and turned into some plates of plastic with coverage of wood.

Nebeker:

Put onto a chassis?

Holst:

Put to a chassis, and top was aluminum, a small plastic wood front, and plastic wood sides.

Nebeker:

I see. I see.

Holst:

Then the cabinet had disappeared, yes.

Nebeker:

Did that become standard?

Holst:

Yes. Yes.

Nebeker:

Was Bang and Olufsen one of the first to do that, you think?

Holst:

Yes, yes.

Collaborations with designers; components and design process

Nebeker:

I see, so, in this case, you were telling me about, with the radios, and Jacob Jensen, you told him that, okay, we have this capability with transformers, we have the capability to produce aluminum surfaces that will be satisfactory as the outside of the cabinet, and then he comes up with some designs?

Holst:

Yes.

Nebeker:

And you have a meeting with him?

Holst:

Larger meeting, larger meeting, with dozens, many of these dozens were headed by Jens Bang....

Nebeker:

What people were present at these meetings of designer and company people?

Holst:

Project leader....

Nebeker:

Project leader, yes.

Holst:

And, couple of designers, Jens Bang, and Jacob Jensen. Sometimes I participate, sometimes others did participate, and the leader of the mechanical department participated.

Nebeker:

Okay, now is that a time when, well, you said there were a lot of meetings. So you have some meetings when the interests of marketing people, and maybe the interests of technical people are expressed to Jacob Jensen, he goes back, and comes back with some prototypes, or some ideas?

Holst:

When you say express to, it’s a little too hard, it was discussed, what changes did we want, what changes were possible, to try to follow the intentions that you picked up during the meeting, and let us meet in a fortnight.

Nebeker:

I see. And then the same group of people would come together again, and then the, Jacob Jensen, for example-

Holst:

Presented a new idea that was accepted or not accepted, or else, or changed in small areas, and then started. We took the time to do it.

Nebeker:

And there would typically be a number of meetings before arriving at a design that would go into production?

Holst:

Yes, yes, yes.

Nebeker:

And it was the responsibility of the technical people to say before it gets to a later stage that this isn’t going to be possible?

Holst:

Yes, and then one of these, as I said, one of these pluses was that, he knew how hard to press.

Nebeker:

What, now was it always the case that the designer had rights over the design, or could the company decide, you know, after going to production, oh this is too much trouble, or too expensive to do it that way, let’s, let’s round the corners, or-

Holst:

It never came to such extremes.

Tape recorder development

Holst:

We discussed, we cooperated, so, I remember, I remember that big, big tape recorder that was one of the last reel-to-reel tape recorders, a half-professional system that was developed, and we gave it up after we had used five million kroner on it. That was one of the big mistakes.

Nebeker:

You mean the development costs for that?

Holst:

Yes.

Nebeker:

So it never reached production?

Holst:

Yes. Because the development took so long time that it got old fashioned, the tape recorders, the compact cassette took over. Yes, I remember, visiting Philips, in one of our routine visits, and I had wanted to make a discussion with some of the company’s cassette people with Philips, if it would be possible to make stereo sound on such a compact cassette. I tried to say to them that we could foresee that we at Bang and Olufsen would like to start, and try to make stereo on compact cassette. It was impossible to commence any real discussion with those people, because they could sell all what they could make of a model with a cheap, mono treatment , so of course, years later came the stereo....

Nebeker:

They just weren’t interested at that time in developing it?

Holst:

They didn’t understand what I said.

Nebeker:

What year was that, can you place that?

Holst:

Well, I was head of development from 1961 to 1972, so, I would guess middle of sixties.

Bang & Olufsen development department structure, management role

Nebeker:

Okay, yes I did want to also get your, your positions within the company. So you came back in-

Holst:

As a development engineer.

Nebeker:

You came back as a development engineer in, what was it, 1956?

Holst:

Yes, 1956.

Nebeker:

And at that time how many people were in the development, how many engineers were in the development department?

Holst:

Ten. Ten engineers in electronics, the same number in acoustics and mechanical.

Nebeker:

Okay, and you said you became head of development in 1961?

Holst:

Yes, of electronic development, we had a peculiar organization at that time. We had one that was responsible for acoustics, one that was responsible for mechanics, and I was responsible for electronics.

Nebeker:

I see. Did that cause any difficulties in coordination, to have-

Holst:

Yes, yes. Because we had difficulties in understanding each other’s conditions.

Nebeker:

So it puts a burden on the heads of these departments to be sure that the development efforts are compatible?

Holst:

Yes, and to be sure that the set was developed as one set, and not three parts that hopefully could stick together.

Nebeker:

Was that organization changed?

Holst:

Yes, late in the 1960s it was changed, so that I got the full responsibility.

Nebeker:

I see. And that helped with coordinating efforts?

Holst:

Yes, yes it did. Our cooperation with both the acoustic and mechanical department improved considerably.

Materials; aluminum and plastic parts

Nebeker:

I know that one thing that Bang and Olufsen has always given much attention to is the materials of the sets, they had specialists in, I don’t know what those would be called, in metallurgy, or in, I don’t know, plastics or whatever?

Holst:

Plastics, yes.

Nebeker:

And was that something you were very conscious of, is that something that the company wanted to put great effort into?

Holst:

Yes. Yes, there was a high degree of consciousness about improving the plastic standard, and the ability to produce difficult plastic parts, yes. Also, the painting process of those aluminum products and plastic parts, was investigated to a high degree.

Nebeker:

So there was a good deal of R&D done in that area by the company?

Holst:

Yes. One of the reasons why Bang and Olufsen survived as the only Danish producer of such things, was that Bang and Olufsen has always put the finish of surfaces, high-

Nebeker:

Placed a high priority on that?

Holst:

Yes. Wood, aluminum, plastic, painted plastic, always we have had difficulties in reaching the standard that we would have. That means both opaque plastic, and solid plastic.

Nebeker:

And I suppose this is also something, that there’s a good deal of interaction with designers, that they would want a certain-

Holst:

Absolutely, absolutely, in fact, we see the same tendency in cars, where the dashboard parts in cars, when they started those plastic parts, they cheapened the, it wasn’t same. Nowadays, you can see that the materials really used for, all the possibilities of the materials has been used so that you get the quality impression.

Nebeker:

And so this was very much in your thoughts, developing these new products, that the materials must look first class.

Holst:

Yes, and it was very very much in, also in the, the people working on the floor, with those materials, would always judge the quality so that it would be a little bit better than we could make it. So if they were around to make the rejections, they would reject more than quality control did, always, they put in that direction. Really a good tendency, but you have to be aware of it and find it, in one way.

Nebeker:

Did you have to learn yourself, a good deal about materials, as head of development?

Holst:

No, because I, when I was responsible for the electronic part of it, and it was the responsibility of the people that would make this.

Management and production, 1970s

Nebeker:

So you were head of electronic development from 1961 to, you said in the late 1960s that you became the head of all development?

Holst:

Yes.

Nebeker:

How long did that, how long were you-

Holst:

Until 1972.

Nebeker:

What happened in 1972?

Holst:

In 1972, unfortunately, I took over production, because production at that time was running really bad, and I was pressed to try to improve it, and I had no background for it, and I came out of it again in 1975.

Nebeker:

And, what were the real problems?

Holst:

The problem for, were, that the production had never been organized as as manufacturing production. It was an overgrown handwork production.

Nebeker:

I know the company grew enormously in the sixties.

Holst:

Yes, yes, and the shop leaders were very current people, they knew their job, but they didn’t have the power to establish a real production. It was blown up handwork.

Nebeker:

I see, so just enlargement of, or what is that, increase of scale of the same production methods.

Holst:

Yes. They didn’t master that. And then of course we had a lot of theoretical people, consultants, Yes, the technical manager in those days, he called one consultant after the other to come and tell him what was wrong, and everywhere we have the people to tell it to us and no one acted according to what they said. They didn’t-

Nebeker:

Could one take their recommendations? I mean, was it possible to-

Holst:

No, not in the form that we were presented. I have seen three different data controlled production systems, trying to be introduced in production, and every one of them was a failure, so that if the shop leaders have not used their good old methods with papers in the drawer, then Bang and Olufsen would have gone bankrupt. So it was unorganized, and I remember saying to the technical manager that this was impossible, because there is no connection to the, between the-

Nebeker:

Steering wheel?

Holst:

The steering wheel and the front wheels. And there was no connection.

Nebeker:

That’s, I’m just trying to understand this, that’s because the production methods, it was just very difficult to make any changes?

Holst:

No but, all the theoretical ideas about how to control the....

Nebeker:

Supply, or?

Holst:

Yes, the flow of equipment, the flow of parts, the stores, the warehouse management, combined with purchase, production planning, we had, the one good system after the other that should work, but it was never introduced so that it worked.

Nebeker:

And why was that? Why couldn’t this work?

Holst:

Because in reality, because none of us understood production. We could see production in-- we visited a lot of companies-- we could see how they produced, see that they had quite a large scale of activity, but we never had the power or background to introduce it. Then we had couple people employed, that, on a theoretical basis, knew everything about production, but they were, partly they had experience, and partly they were never around to really introduce their ideas. So it was-

Nebeker:

So you found it really difficult to improve things in that period, when you were head of production?

Holst:

Yes, it took, really to find out what to place, because, sometimes it was impossible to find out how many TV sets that were produced in one day. Because part of them were not, part of them were rejected, part of them were under repair, and part of them and so on and so on. So just asking how many were produced today was really to cheat. It couldn’t be answered.

Nebeker:

So part of it was these management tools of close accounting of everything weren’t in place.

Holst:

Yes.

Nebeker:

Was there resistance to changing methods?

Holst:

Yes, of course.

Nebeker:

What, what was the upshot of this, the result?

Holst:

The result was that some, some of the leaders of the, mechanical leaders of the mechanical factory, and a new leader of the electronic factory, and people that could understand the combined systems that should control purchase, component flow, stuck all the logistics. People that had better education, better training, and had tried something like production-

Nebeker:

On a large scale.

Holst:

On a large scale, yes.

Nebeker:

And so the situation was gradually improved?

Holst:

Improved, yes.

Nebeker:

But, so you decided after three years that you had-

Holst:

It was decided.

Nebeker:

It was decided [laughter]. After three years, what did you do then?

Intelligent product research

Holst:

Then I took over something that was called intelligent product research. That was the third time I participated in such a job. Because Bang and Olufsen, in those days, had the feeling that it would be a good thing to have some alternative production line, or activity line. We had a Norwegian consultant, who had died many years ago, who through one year, we had weekly, oh, not weekly, but every second week, we had meetings with him and we tried to analyze the changes, you have-?

Unknown:

Sorry to interrupt you.

[Break in recording.]

Holst:

Do you recall what?

Nebeker:

Let’s see, you were....

Holst:

Yes, intelligent products research. We had those meetings with this Norwegian. He was a clever man. And we had a very scheduled project trying to find out what our strengths were, and what our weaknesses were, and how we should improve it, and all that you can do-

Nebeker:

Okay, this is sort of like long range planning for the company?

Holst:

Yes, exactly, yes. Jens Bang participated, Jacob Jensen participated, and couple of people more, people that are not at Bang and Olufsen any more, participated. And we found out that we should try to find something else to do. I was secretary of that group, and we made a lot of analyses, and so on, and so on. And out of it came that, now, this this, what do you call that you put on your lawn?

Nebeker:

Fertilizer?

Holst:

This fertilized, this fertilized the thought that it was acceptable to try to use effort on other areas. We had sent out some signals earlier, and we had a lot of discussion with Jutland Telephone, which was our local telephone company, and it happened that they, they wanted, due to an excellent managing director, they wanted to do something for the [unintelligible]. So they came up with various proposals for us to make something that was not radio or TV. Maybe you should take it a little backwards, and this was the third time that I participated in such a challenging product research, because Bang and Olufsen had, during the low periods, we had idea that we should try to have something else to do, and in one of those periods, we started making medical equipment, and seen in hindsight it would be stupid if we didn’t continue, because we really had some feeling for it, and could have played the cards in a lot better way.

Bang & Olufsen medical equipment, 1950s-1960s

Nebeker:

What period was that that you produced?

Holst:

That must have been around 1963-64, I guess.

Nebeker:

What sort of medical equipment?

Holst:

We made, in 1952 Bang and Olufsen started making respirators, we had a polio epidemic, and many people were almost dying from suffocating. The head of the acoustical department made equipment that could blow air into the lungs, and when the lungs had collapsed, and it accepted that the air would flow out again and then it would empty. So, that was one of the first things, and later on, we developed an equipment that could find mechanical parts in the-

Nebeker:

In the body somewhere?

Holst:

In the body, yes.

Nebeker:

So, pieces of shells, or-

Holst:

Yes, or injection needles. I saw something about anoperation where they tried to find such thing had broken-

Nebeker:

The needle.

Holst:

Bloody affair, but....And we had an excellent equipment then. 25 years later, a doctor came and asked if he could make service on it. We had given up 20 years ago.

Bang & Olufsen collaboration with Jutland Telephone

Holst:

But there in the mid-70s, we came really into contact with Jutland Telephone, and the managing director, Mr. Relsted, and the head of the technical, of the development department with Jutland Telephone, Kurt Vestergaard, they came and told us we should make concentrators, yes, we should make concentrators. We didn’t know what a concentrator was at that time. I had the feeling that the telephone world was still using analog instead of digital, and they had given it up three years earlier, so I was not well informed. [laughter].

[End of tape one, side b]

Holst:

- Audio File

- MP3 Audio

(307 - holst - clip 3.mp3)

...small activity in cooperation with Jutland Telephone, I employed one man from the television department and one from outside, and he, the guy from outside, he knew something about telephones, that was a luck for us, because we didn’t know anything about them. We knew something about reliability, that was one of the key points. We set our contract with Jutland Telephone to make this development until early in ‘79, and we got financial support from one of the Danish governmental foundations that had the task to support some activities, we got an excellent treatment from them. We succeeded in following the plans. We started in ‘78, and we made the first development contract in ‘79, and that contract included that we should have an operating model early in ‘83, and in ‘83 we made a supply agreement with Jutland Telephone according to which we should supply for 40 million Kroner concentrator equipment to Jutland Telephone. Then we followed the plans, we even made in cooperation with Jutland Telephone much more development than we were obliged to. The idea was to make front end of electronic, of big electronic switches, front ends that could be placed in the neighborhood of the subscribers. Normally it is so that the front ends are placed in the rooms where the big electronic switches are placed. But there are certain advantages in, in making, using, piecing connection to, to concentrators that you place where there are concentrations of subscribers.

Nebeker:

Okay, you said PCM connections?

Holst:

Yes.

Nebeker:

So the idea is closer to the subscribers you have that conversion from the analog signal on the telephone?

Holst:

The-, yes. Yes, yes. So that the subscriber lines are shuttled in that way because they only go to this concentrator that is placed near the subscriber concentrations. We supplied as we should during, from ‘83 and further on, and we had placed in a corner of the Bang and Olufsen buildings, and at last in ‘85 we found out that we should build our own buildings for this and e make them in the southwestern part of the town here. Again all this development was heavily supported by this development foundation that the government has. But we paid them every cent that they lent to us, that we borrowed from them.

Nebeker:

Oh, these were just loans from the government?

Holst:

They were loans, yes [laughter], they were loans under special conditions. If we succeeded we should pay back, but if we didn’t succeed, we should send them a letter, we have given up, you may take, you may take over everything we have developed, and we don’t owe you a penny. That was one of the conditions. And we had, we had troubles with the

Nebeker:

The accountants?

Holst:

The accountants every year, because they couldn’t understand a loan under those conditions. [laughter] They would say, but you owe them 20 million Kroner! No, we don’t owe them! But you are loaned, you are loaned! Yes, we, we are borrowing 20 million, but we don’t owe them a cent! [laughter] They couldn’t understand it. But after all we paid them back. And now, I left this activity. First it was called the koncentrator department in Bang and Olufsen, digital koncentrator, that’s a concentrator with a ‘k’ as it is in Danish, and then in ‘90, half of the activity was sold to Ericsson Company, and it was established as a separate company, half owned by Bang and Olufsen, half by Ericsson

Nebeker:

You said that’s part of this effort, or the whole?

Holst:

The whole of it.

Nebeker:

The whole of it, I see.

Holst:

The whole of it, yes. At that time, we were 150 people in this activity, and out of them 90 were engineers, all highly educated technicians, so then most of the people were engineers-

Nebeker:

So these concentrators were sold to Jutland Telephone?

Holst:

Yes, and then of course we tried to start some export also, had limited success, and the idea was that anything should be able to use this concentrator and set it together with their equipment. In fact Jutland Telephone, they had much of their switch lines from Ericsson, so therefore, our concentrator was developed to cooperate with one of the big Ericson switches. I was a technical manager of this company from ‘92, and exactly three years ago on the first of August, then I retired, age 65-

Nebeker:

So this is entirely, this is a new company that was set up, and Bang and Olufsen owns half of the stock and Ericsson half of the stock?

Holst:

Yes, and nowadays Ericsson owns 75 percent and Bang and Olufsen 25 percent. So, well, in reality it was what we always looked upon Ericsson as the enemy [laughter]. And then they bought the activity.

Nebeker:

It seems remarkable to me that, I’ve talked to some switching engineers, and there’s such a history of development of switching technology, and in the electronic era as well, that your relatively new group would be able to make a contribution. Maybe this, does this have much to do with switching, these concentrators?

Holst:

Yes, a concentrator is part of switch. And yes, it is, it is switching, as switching is, yes.

Nebeker:

But it’s remarkable that, you know, you would be able to move into that area and make a contribution to it.

Holst:

Yes, yes. But the actual cooperation with Jutland Telephone came as a lot of our know-how. And then of course also employing the right people was one of the things that I did. Had to do, to be able to make success.

Nebeker:

Yes, well that’s, that’s very impressive, and Ericsson obviously must set some high value on this since they have invested in it.

Holst:

Yes, yes, and they are, they are, they are still increasing the activity, they are 200 people at the moment, and still going, and now, five-six years after they took over they start understanding what it was that they bought. They could see that they bought a well operating development team, and a good connection to the Danish telephone companies, but they didn’t really accept the products that we produced. First now, I can, I sometimes visit them, and now I can feel that Ericsson is starting to understand what they have bought.

Nebeker:

So originally maybe their principal motivation was the good connections with the Danish telephone system?

Holst:

Yes, and, and stopping something that they didn’t like, because with such very big switches that Ericsson sells, they earn a lot of their money on the subscriber side of those switches. And if then such a newcomer like us would come and start selling the subscriber parts at lower price than Ericsson is offering, it could depress the whole price level for big switches. So, and then it turned out that we had some sort of a success, and our idea, Jutland Telephone’s idea, was a good one. So they have in some way or another to get control of this activity.

Nebeker:

I see. Their position as principal manufacturer of switching equipment, they wanted to be in control, or, or-

Holst:

Yes, of course, we couldn’t, capacity-wise, we couldn’t be a threat to them at all, but proving that things could be solved in a much much cheaper way, and maybe getting attraction from some other of the big telephone companies, that would be a bad idea....

Nebeker:

Was there something in your training or experience or other people’s that was transferable directly to this development effort?

Holst:

Yes and no. The Bang and Olufsen idea about all of this knowing what we were doing, I mean never just copying a radio research laboratory schematics, but knowing exactly what we had between our fingers, that’s some sort of development company spirit that Bang and Olufsen has always had. Some of the people fixing, the first one I hired to participate in the [unintelligible] activities, came from TV, and the people from that group have had lots of discussions with the Philips people about deflexing systems in TV sets, color TV sets, and they have often forced Philips to change their development because they found out that something was wrong, and they could argue with the Philips people, and tell them. And this way of thinking, never crossing the fence where it is lowest, but always trying to make the proper solution was part of the background that I came with and we came with. And we hired people that had a telephone education, and of course we let them, I let them be responsible for the things that they knew about.

Nebeker:

You were actually producing for some time these concentrators, is that right?

Holst:

Yes, we are, they are still producing those concentrators. And in ‘88, we started changing the concentrator to an ISDN switch, and we had an operating ISDN switch a long time before the Ericsson switches could. The Ericsson switches are the most used switches in Denmark, together with Siemens switches. They couldn’t handle ISDN for many years, when we could. It was something of an achievement to develop on the basis of the concentrator such a small ISDN switch. And also there we have excellent support from this development foundation.

Retirement

Nebeker:

You said you retired three years ago?

Holst:

Yes, exactly.

Nebeker:

And you haven’t taken other work since then?

Holst:

I have had a [unintelligible] with a company making windows, and in fact they gave me this roof that, that [laughter], but, it ended in, well, there were troubles, so this, I work for one year and a half. Partly as a head of the [unintelligible] management for a daughter company making roof windows, but, well I had absolutely no experience in windows before that, but I had some experience in development, and I could, of course lead or guide their development efforts. They had no experience in development. But due to various conditions that, well, I didn’t like it.

Evolution of the Danish economy

Nebeker: