Oral-History:Alfred N. Goldsmith

About Alfred N. Goldsmith

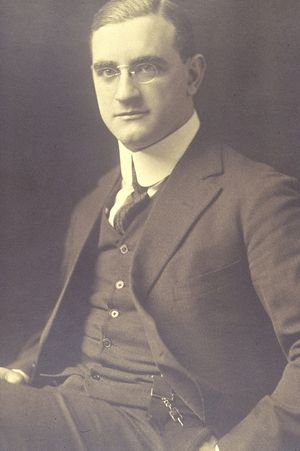

Dr. Alfred N. Goldsmith obtained his bachelor's degree in 1907 from City College, and his Ph.D. from Columbia University in 1911. He taught at City College from 1906 to 1923. Goldsmith worked for General Electric Company and Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of America. In 1919, he joined RCA, where he held a variety of positions, including vice-president of RCA Photophone, and vice president in general engineering. Goldsmith received over one hundred patents in the field of electronics and was director emeritus of the IEEE. He was a founding member of the IRE, first editor of the Proceedings of the IRE, and a member of the IRE Board of Directors for its entire existence.

The interview begins with a discussion of Goldsmith's role in the founding of the IRE. Goldsmith mentions his work with Ernst Alexanderson, William C. White and Irving Langmuir. The interview then moves to a discussion of Goldsmith's studies under Michael I. Pupin at Columbia University, and Pupin's patent dispute with George Campbell. Goldsmith goes on to discuss his 1915 radio transmission tests between New York and Germany and with Hoyt Taylor from North Dakota to New York. The interview concludes with remarks concerning Goldsmith's development of the basic idea of colored radio telephony and his invention of remote control for television.

About the Interview

Alfred N. Goldsmith: An Interview Conducted by E. Kenneth Van Tassel, Center for the History of Electrical Engineering, March 1974

Interview #023 for the Center for the History of Electrical Engineering, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc.

Copyright Statement

This manuscript is being made available for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the IEEE History Center. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of IEEE History Center.

Request for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the IEEE History Center Oral History Program, IEEE History Center, 445 Hoes Lane, Piscataway, NJ 08854 USA or ieee-history@ieee.org. It should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user.

It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows:

Alfred N. Goldsmith, an oral history conducted in 1974 by E. K. Van Tassel, IEEE History Center, Piscataway, NJ, USA.

Interview

Goldsmith's Educational and Career Background

Van Tassel:

This is an interview with Doctor Alfred Norton Goldsmith, Director Emeritus of the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers. Doctor Goldsmith was born in New York City on September 15th, 1888. He attended City College and obtained his bachelor's degree in 1907. He obtained his doctor’s degree from Columbia University in 1911. He was a Phi Beta Kappa. In 1930 he married Maud Johnson. He taught at City College from 1906 to 1923. He is a life associate professor of electrical engineering, and was a construction engineer for General Electric from 1914 to 1916. He became director of research for Marconi [Wireless Telegraph Company] of America in 1917 to 1919. He then became director of research, chief broadcasting engineer, the vice president of RCA from 1919 to 1933. In addition he was chairman of the board of consulting engineers for the National Broadcasting [Company], and vice-president of RCA Photophone from 1928 to 1931. He also was vice-president in general engineering for RCA from then on. He has acquired over one hundred patents in the field of electronics. He has written several books and numerous papers, and he been honored by a long list of organizations. Among these are the National Pioneers in 1940, the Medal of Honor from the IRE in 1941, and Television Broadcasting Association Medal in 1945. Dr. Goldsmith, can you tell us about the Radio Club of America, and how the IRE was founded?

Formation of the Institute of Radio Engineers

Goldsmith:

There were in existence around 1910 to 1912 two major societies in the radio field. One was the Society of Motion Picture Engineers.

Van Tassel:

Good.

Goldsmith:

It was headquartered in Boston, and was under the tutelage and presidency of John V. L. Hogan. The other was the Wireless Institute, which was under the presidency of --

Van Tassel:

Goldsmith:

- Audio File

- MP3 Audio

(023 - goldsmith - clip 1.mp3)

Of course. Robert H. Marriott, who was at the time the chief engineer of a radio service for what was called the [United] Wireless Company of America. It no longer exists. These two societies each had a couple of hundred members, and were competitive in a sense, and not in the least co-operative. This was a deplorable state of affairs because in a small and growing field, one really needed an adequate concentration of effort and time and energy. Consequently, a number of us, notably Robert Marriott, felt that there should be a single society brought about through the combination of the two. This was much more difficult to do than might be regarded as possible, because each of the societies wanted to be the kingpin, and consequently each of them was vying for the presidency and the title of the new society if there was one. It was agreed that there should be one.

Van Tassel:

Yes.

Goldsmith:

It was not agreed that they should combine, or if they did combine, that they would have a name that would not favor either one of them. The problem was solved by your humble servant in a very simple way. The Boston-based Society of Wireless Telegraph Engineers, gave part of the name of the new society, and the Wireless Institute in New York gave the rest. The two names, the Wireless Institute and the Society of Wireless Telegraph Engineers combined to form the Institute of Radio Engineers.

Van Tassel:

Yes.

Goldsmith:

So the name was a compromise of two organizations which were otherwise duplicating their efforts. The first president was Robert Marriott, and thereafter came a succession of presidents, the latest of whom was the fiftieth president.

Van Tassel:

Goldsmith:

He later became president of the organization down in Texas, I think. It produces great quantities of solid-state equipment.

Van Tassel:

Texas Instruments?

Goldsmith:

Texas Instruments. He was its president, and he became president of the joint society up here.

Van Tassel:

Yes.

Goldsmith:

And this name was really adopted as a convenient and correct name for the organization.

Van Tassel:

Can you tell us some of the first meetings that you had with Mr. Hogan and Mr. Marriott at Columbia? The three of you met together?

Goldsmith:

We met there and fought it out, so to speak. Thereafter we met a number of times down in Fulton Street, at the White Restaurant, and hammered out details there. Hogan, Marriott, and myself. These were the three.

Early experience with DeForest's Audion, vacuum tubes, and radio transmission

Van Tassel:

Well, way back in the earlier days, you had some experience with the De Forest Audion?

Goldsmith:

That is right. They were used at the time as detectors of the crystal type, crystal detectors. Galena?

Van Tassel:

Galena crystals, yes.

Goldsmith:

And various other crystals. A common figure at the time also was the one of the hard-working presidents of the IRE, namely [Greenleaf] Pickard.

Van Tassel:

Pickard, yes. I believe this early vacuum tube was manufactured by a man named --

Goldsmith:

[Henry] McCandless, who was a manufacturer of vacuum tubes down on the lower east side of New York City, and therefore seemed to be the logical person to make vacuum tubes for the general sales. He was able to produce a product that was far from uniform. The vacuum in it was sometimes very high vacuum, and sometimes very low. The result was that conductivity was readily enough initiated in these vacuum tubes, and the residual gas in there became conductive. The tubes which were hitherto high vacuum and invisible, or reasonably high vacuum, would glow a bright blue. It was everybody's wish to own one of them because they were of course far more sensitive, and unusually more dependable than the cat’s whisker, the galena crystal.

Van Tassel:

May we also ask you about 1915 and 1916, when you conducted some experiments in radio transmission? You had a nice big five-kilowatt radio set.

Goldsmith:

I was at the time a consulting engineer for the General Electric Company and I worked with E. F. W. Alexanderson, who was the chief engineer in the radio field for General Electric in Schenectady. I also worked with W[illiam] C. White, who was the vacuum tube man, and at times with [Irving] Langmuir, who was of course a very eminent scientist and who made available the first of the high vacuum tubes. There was quite a struggle between Langmuir’s high vacuum tube and the circuitry and tubes of Dr. George Campbell in Bell Laboratories.

Van Tassel:

Yes. Campbell and Arnold.

Goldsmith:

Campbell had put in a patent application on the tube, and their use over long distance telephone circuit amplifiers. He was competitive in this theorem with Michael I. Pupin, who was a professor of electrical engineering and physics up at Columbia University.

Goldsmith's studies at Columbia University

Van Tassel:

You, I believe, were the student of Dr. Pupin.

Goldsmith:

I studied under Pupin, who was a very temperamental and very capable person, and a very difficult person. He had odd ways of emphasizing things. He would, for example, get his class in a large classroom and lecture to them. When he got two-thirds of the way through he would say, "No, I do not like this." Pupin had an accent, and he would rub out the whole thing he'd done and start all over again.

Van Tassel:

Yes.

Goldsmith:

He was very difficult that way. He spoke so rapidly and made so many changes in his material, and the field was so dubious, that it became necessary for us to team up. I teamed up with an elderly gentleman who was very bright, and each of us took notes. We then combined our notes over the lectures and used those to study the fifteen lectures on high voltage and tubes. I didn't know anything about my partner, but one day I happened to mention that he and I were working together to a third man and he burst out laughing. He said, "Do you know who he is?" I said, "No, I have no idea who he is, but I know he seems to get the material very rapidly and we work together nicely." He said, "Well, he happens to be [Cyprien] O. Mailloux, president of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers."

Van Tassel:

Very interesting. That's nice. What were some of the kinds of topics that were taught in colleges at that time?

Goldsmith:

Well, advanced physics.

Van Tassel:

Advanced physics.

Goldsmith:

And electricity. And, of course, typical college material. The particular thing that Pupin was emphasizing at the time was the induction motor.

Van Tassel:

The induction motor, yes.

Goldsmith:

Induction motor and generators. These were therefore emphasized in his lectures, and he got into squabbles with German inventors, who were working in that field. However, in the field of Bell Laboratories, the Bell Laboratories people were very cooperative and wise. They made an arrangement with Professor Pupin, who competed for claim over a theorem with George Campbell, and this theorem involved loading on long distance telephone lines as I said earlier. If Campbell won the contest over the theorem, Pupin was out, that was the end of him. If Pupin won the battle for the theorem they would buy a patent from him. I think he got about seven hundred and fifty thousand dollars payment for the patent and its rights.

Van Tassel:

Yes.

Goldsmith:

And that was the start of his fortune.

Van Tassel:

Seven hundred and fifty thousand dollars is a good start on a fortune, yes. Apparently Pupin won the patent case.

Goldsmith:

He did win. At the time, I worked not only with the General Electric Company and W. C. White and Alexanderson, but also with various other people up in Schenectady who were cooperative.

Van Tassel:

Were you acquainted with Mr. Charles Steinmetz?

Goldsmith:

No. He was a brilliant hunch-backed gentleman, and extremely important in the field of electrical engineering, as you know. I don't need to go into that.

Goldsmith's 1915 radio transmission test

Van Tassel:

No. Let's go back to the 1915 radio transmission test that you conducted out to North Dakota.

Goldsmith:

Yes. I was very desirous of carrying out real experiments over considerable distances. The first thing I tried was reaching the Germans. They had a transmitter and receiver at Nauen near Berlin. This was a high-power transmitter with multiple amplification and repetition. They ran the thing, and I received it at Sayville, Long Island, with a receiving station of ours, and there was a transmitter there of the same type as in Nauen. That circuit from Sayville to Germany was so feeble that the cable that came from the receiver to the receiving set that the operators used was kept away from anything it could rub against because if it rubbed against something the signal was drowned out.

Van Tassel:

With the static and the noise that it would pick up?

Goldsmith:

Yes. You can tell what the signal was like.

Van Tassel:

How weak.

Goldsmith:

Yes.

Van Tassel:

And your transmitter was in the neighborhood of five kilowatts?

Goldsmith:

No, it was more than that. It was around ten kilowatts. Amplification and repetition.

Van Tassel:

You also worked, I think, with Hoyt Taylor.

Goldsmith:

I put this transmitter into my laboratory, which was the City College of New York, where I was a professor of electrical engineering. I started transmitting in the late fall of 1914. I transmitted up the Hudson valley, to Schenectady. The signal was gorgeous. You would have thought there was a telephone line between my laboratory and the laboratory in Schenectady, but by February of the next year, static had come up tremendously and you couldn't hear a thing, so it was useless.

Van Tassel:

Was this like an aurora borealis that was causing this type of thing?

Goldsmith:

No, it was a short. Now, I also wanted to reach Nauen and hear them, so I got up on the top of a high cliff near the City College of New York, near my laboratory, and tuned in to Nauen. I had the circuit running from Nauen to Sayville very nicely.

Van Tassel:

This was a telegraph service?

Goldsmith:

That was a telegraph service. There was no telephony.

Van Tassel:

No telephony at that time, that's right.

Goldsmith:

You wanted to talk about Hoyt Taylor. Hoyt Taylor was a professor at Grand Fork, North Dakota, and we had an arrangement that we were going to work together. I started sending, and he started sending along about ten or eleven o'clock at night on the days that we worked together. The signals were received at my laboratory and sent up to the Western Union telegraph office about a quarter of a mile away. This was, I think, one of the first, if not the very first, telephones. Because that was telephone.

Van Tassel:

Yes, that would be telephone. And they transmitted your detected signal over wire. Was that the same office as on Hudson Street now?

Goldsmith:

Oh, no, I don't know that.

Goldsmith's development of tubes for colored television and television remote control

Van Tassel:

All right. Let us change the time and talk some about this new field that you enjoyed working in: television. You developed and pointed up the first way of having colored tubes. Can you tell us some of those stories?

Goldsmith:

I became very interested in the next few years in radio telephony. I ran into real difficulties because there wasn't enough power available. You needed much more power for this sort of telegraphy. I hit on the idea that we had to have some way of picking up signals and getting them in color rather than black and white. The method that I used was rather an adaptation, I believe, of something done earlier, namely telephony over wires. I got my signals from Schenectady and tuned them in, and I invented at that time the basic idea of colored radio telephony.

Van Tassel:

The color was coded and you used the three primary colors.

Goldsmith:

Red, green, and blue.

Van Tassel:

It was your idea of locating those as separate entities on the face of the tube?

Goldsmith:

That's right. They were zones or spots. An electron beam came from three guns. It started from the far end of the tube, went through the tube, through the focusing hole, and then out. Then it hit the desired spot and had to be very accurate.

Van Tassel:

Yes. Accuracy was a very important part. I do believe you also, in connection with television, are responsible for or invented what is called remote control?

Goldsmith:

That is right. I wanted to use a receiving set in the home and transfer and amplify the signal to a large speaker, amplify to a large speaker across the room. How to transfer it across the room? One way, of course, was just to go under the carpet.

Van Tassel:

With wires.

Goldsmith:

Which was, of course, very obnoxious to the lady of the house. Another way of doing it was to use a modulated tone. Well what kind of tone? If I used a very low pitched tone, it would be heard. If I used a very high pitched tone, it would be absorbed in the walls and actuate neighboring receivers. So I hit on tones in the tens of kilocycles. I modulated that, and used that for the transmission of the tone from the receiving set to the controls of the receiver.

Van Tassel:

So you were using acoustical sound in the tens of kilocycles.

Goldsmith:

That's right.

Van Tassel:

By being acoustical, this limited the control to a specific room.

Goldsmith:

And to the party which one wanted. Dr. Taylor was sending signals after he joined the Navy across the Potomac and receiving in Virginia. He found that at the receiving station, the signals dropped in intensity very markedly every time a big size boat went through the beam. This gave him a clue: Here were radio signals which were being absorbed or reflected.

Van Tassel:

And from this point of view he began to expand?

Application of television to medicine

Goldsmith:

- Audio File

- MP3 Audio

(023 - goldsmith - clip 2.mp3)

And he did expand over in Camden, New Jersey at the RCA Laboratory there, and work ahead with his radar concept. Norton Watson Weiss was trying the same thing but he was sending signals vertically to the reflecting lamp and then back to the ground. So the two of them had competing concepts. I was always very much interested in two fields, not one. One of them was radio, and we have been talking about that, but I was also interested in medicine.

Back at that time, I actually sent short waves from the laboratory at Camden to a hospital about a mile or two away and they sent the picked-up signals back to the laboratory in Camden and it was used to produce color signals. The difficulties there were not overcome. It seems that there was a man over at the hospital who was being operated on, they thought he had cancer in the colon and they sent signals back and forth between the two locations, and seated next to me in the lecture room was a professor of electrical engineering in physics from Japan.

The signal was picked up in this hospital and sent to receiving equipment. It was so clear that it was possible for them to see at the other end and in the laboratory at Camden, that the signal was being received and being received clearly. This was in a tile room with several hundred physicians there. They could see the operation taking place; then there was a hush because they saw instantly he didn’t have cancer, it was a benign tumor.

Van Tassel:

In this way it was the first operation in which people at remote distance could view it and observe it through television.

Goldsmith's awards and achievements

Van Tassel:

I am standing at the moment in Dr. Goldsmith’s study. Looking on the wall at the numerous awards that he has received through his fine work. One outstanding award is signed by some fifty presidents of the Institute of Radio Engineers. In this award the following paragraph states their esteem for him. “As a token of our lasting esteem and affection for one who has thus so ably served with each and everyone of us during our terms of office, we the presidents of the IRE, speaking for those departed as well as for those present offer this inscribed testimonial as a remembrance of the Golden Anniversary Banquet of the IRE.”

In another award, Dr. Goldsmith is made a fellow of the College of International Surgeons, testifying to his real interests to the medical profession as well as the electrical and the electronics.

He was cited by radio pioneers in 1952, and given a special citation for outstanding service and contributions to radio. He was given a testimonial by the National Television Film Council. He was made a fellow of the American Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers, which was organized in 1884. Dr. Goldsmith was a vice-president of the Pan-American Medical Association, and in that regard received awards and notations to that effect. There is a fine certificate in his office, showing the Institute of Electrical Engineers that he is a certified fellow and this is dated March of 1969 – that’s from England. He was also a fellow of the Australian Institute of Electrical Engineers. Dr. Goldsmith was awarded the first television tube off of the production line. He has this tube nicely arranged and organized in his study; it is on display here. The inscription above the tube states, “RCA Laboratories Award for Outstanding Work in Research presented to Alfred Norton Goldsmith for his early recognition of the importance of a tri-color kinescope and for his concept of means for accomplishing it.”

He is a senior member in the American Astronomical Society, as well as a fellow of the New York Academy of Science. He has been recognized and made a fellow of the Australian Institute of Radio Engineers, the American Rocket Society, the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts and Manufactures in Commerce in London have certified that Mr. Goldsmith has this day been elected a Benjamin Franklin Fellow of the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts and Manufactures in Commerce. A member of the American Physical Society, honorary member of the Society for Motion Pictures and Television Engineers. And he also has an award for the recognition of services freely given in order to meet a national need through the development of American War Standards. “This certificate is awarded to Dr. Alfred N. Goldsmith for the members of the War Committee of this association whose devoted labors have served government, management, and workers well. Their work has been singly honored by the Award Armed Forces and is gratefully acknowledged by the American Standards Association.”