Oral-History:Hans Wilhelm Schuessler

About Hans Wilhelm Schuessler

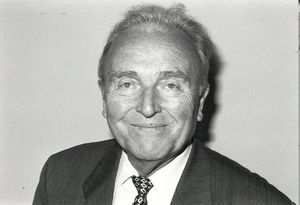

Dr. Wilhelm Schuessler was born in Germany in 1928. He received his Doctoral degree and his Habilitation from the University of Aachen, Germany, in 1958 and 1961 respectively. From spring 1961 to fall 1962 he was Lecturer at that University. During the academic year 1962 - 1963 he was Visiting Assistant Professor at the Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. In 1963 he became Associate Professor and in 1964 Full Professor for Communication Systems at Karlsruhe University, Germany. In 1966 he joined the newly founded School of Engineering at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany, as Professor for Telecommunication. In 1974, 1976, 1984, 1989 and 1994 he worked for some months as a Visiting Professor at the MIT, Cambridge, Rice University, and the Technical University of Vienna respectively. He was General Chairman of the first conference on Signal Processing in Germany, organized for the NTG in 1973, the 2nd European Signal Processing Conference (EURASIP) in 1983 and the International Symposium on Signals, Systems, and Electronics (URSI) in 1989, all in Erlangen. Schuessler became a Fellow of the IEEE in 1977 [fellow award for "contributions to the theory of analog and digital filters"]. His IEEE awards include the Centennial Award and the Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing Society's Society Award (1979). H. W. Schuessler has taught courses in network theory, system theory, communications, analog computers and digital signal processing. He is the co-author of Computer-Based Exercises for Signal Processing Using MATLAB, Digitale Signalverarbeitung. Band 1 [Digital Signal Processing, Volume I, 4th Edition] Netzwerke, Signale und Systeme I and Netzwerke, Signale and Systeme II.

This interview focuses upon Dr. Schuessler's career, particularly his developments of digital filters for signal processing and his publications. Schuessler discusses the influential publications in the field and the initial reluctance of industry to value the applications of digital signal processing. In addition, Schuessler notes the dominance of the United States in the field, giving the fact that the United States has more universities teaching digital signal processing as a part of the regular curriculum as reason for this dominance. The interview closes with Schuessler’s thoughts regarding the current state of the field and the many applications of this technology.

Other interviews detailing the emergence of the digital signal processing field include C. Sidney Burrus Oral History, James W. Cooley Oral History, Ben Gold Oral History, Alfred Fettweis Oral History, James Kaiser Oral History, Wolfgang Mecklenbräuker Oral History, Russel Mersereau Oral History, Alan Oppenheim Oral History, Lawrence Rabiner Oral History, Charles Rader Oral History, Ron Schafer Oral History, and Tom Parks Oral History.

About the Interview

HANS WILHELM SCHUESSLER: An Interview Conducted by Frederik Nebeker, Center for the History of Electrical Engineering, 21 April 1997

Interview #335 for the Center for the History of Electrical Engineering, The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc.

Copyright Statement

This manuscript is being made available for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the IEEE History Center. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of IEEE History Center.

Request for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the IEEE History Center Oral History Program, IEEE History Center, 445 Hoes Lane, Piscataway, NJ 08854 USA or ieee-history@ieee.org. It should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user.

It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows:

Hans Wilhelm Schuessler, an oral history conducted in 1997 by Frederik Nebeker, IEEE History Center, Piscataway, NJ, USA.

Interview

Interviewee: Hans Wilhelm Schuessler

Interviewer: Frederik Nebeker

Date: 21 April 1997

Place: Munich, Germany

Childhood and education

Nebeker:

Could I ask you first about your family and your early education?

Schuessler:

I was born in 1928. My mother was alone, since my parents had divorced, and that had some influence on my career since my mother couldn't send me to high school. I spent six years at elementary school, and had a very nice teacher who knew of a possibility to get not just a higher education but an education on the average level, the so-called Mittelschule.

Nebeker:

Where did you spend your childhood?

Schuessler:

In Dortmund, in the Ruhr region. At my Mittelschule the curriculum was six years, and I had to step into the third year and finish the whole thing in four years. I did. I had the idea to become an engineer, but it was right at the end of the war. I finished this school in 1944. It was somewhat difficult, of course.

Nebeker:

Do you mean the living conditions during the war?

Schuessler:

Yes. I was just coming to a new school, now called Fachschule, but was at the time it was simply called engineering school. It was for people just coming out of this Mittelschule. At this time the school I was attending in Dortmund was destroyed. Firstly, I was made a Lehrling.

Nebeker:

An apprentice?

Schuessler:

Yes, an electrician’s apprentice. When I finished that, I became an electrician. In 1948 I entered the school of engineering as a student, and at that time we had to pay for tuition. Of course I didn't have any money, especially since the currency changed in post-war Germany. The Deutsch Mark was introduced in the summer of ‘48. I had a hard time then, going to school in the morning and working in the afternoon.

Nebeker:

This was working as an electrician?

Schuessler:

Yes, I worked for two and a half years. I finished school after five terms—five semesters.

Nebeker:

Which degree was that?

Schuessler:

The degree was Engineer.

Nebeker:

Not Diplomengineer?

Schuessler:

Today it's called Diplomengineer, but that was not the name at that time. I got permission—due to some scholarly success—to go to the university. I went to Aachen and continued studying and started a new university career. You see, I never got an Abitur.

Nebeker:

That's unusual, I take it, to go to university without Abitur.

Schuessler:

Well, it was permitted to do so.

University of Aachen

Nebeker:

Were you studying electrical engineering at Aachen?

Schuessler:

Yes, studying electrical engineering, and I finished my studies in seven semesters, which, though not very common, is not a record. There were some colleagues who did it faster than I.

Nebeker:

Did you know Professor Döring at Aachen.

Schuessler:

Professor Döring? He started at Aachen, as far as I can recall, in ‘52 or ‘53. I listened to his first lectures on high-frequency circuits and the like and he wanted to ask me to become his assistant. But at that time his colleague, Professor Ashov had already asked me to assist there. I had already agreed, and that's why I became an assistant with Professor Ashov.

Nebeker:

What were you working on?

Schuessler:

Telecommunication. Not high frequencies, but more or less transmission over wires in the low frequency range. At that time, these two professors said that the limit between them both is a range of 1 MHz. I finished the Ph.D. in ‘58. I continued to work with Professor Ashov. In the next three years I did my habilitation, or admission as a university lecturer, and became a dozent (lecturer) at Aachen.

Nebeker:

What was the work of your habilitation?

Schuessler:

My habilitation was about the use of analog computers: the use of analog computers for representation, for example simulation of electrical networks, LC networks, and filters of that type. Later in the interview I will come back to that point and say something about the early connection to digital signal processing.

Professorships at Cornell, Karlsruhe, and Erlangen

Schuessler:

I then had the chance to go to the United States to Cornell University as a visiting assistant professor in ‘62. At that time I already had an agreement with Karlsruhe University to become what is today called an Associate Professor for Communications. The university agreed that I could go to Cornell first for a year, and in 1963 I came back and worked there for two and a half years building up a new institute by the way which had just been founded.

Nebeker:

What was the institute called?

Schuessler:

The name is now Institute für Communication Systems.

Nebeker:

What was it then?

Schuessler:

I invented this name. Earlier, I think it was just Communication. There was already a main institute—an institute for all communication. I didn't have a separate institute; it was a chair of communication systems.

Nebeker:

By "building up," do you mean that you brought students and assistants?

Schuessler:

Yes. There was nothing before it. We started from scratch. Then I got an offer to come to Erlangen. Erlangen had the idea to introduce or found a school of engineering, which was uncommon: this was the first old German university to do that. This was a challenge, and that's why I came to Erlangen, where I still am.

Nebeker:

What was the position that you accepted at Erlangen?

Schuessler:

Just a professorship, nothing special.

Nebeker:

There were a number of professors starting this?

Schuessler:

We started electrical engineering; there had been three professors in the very beginning. This number increased somehow, but I was just the chair for communications. Maybe one point might be of interest. Already at Aachen and later on at Karlsruhe, I had a good connection with the computer people. That was true for the first computers they built or they bought in Aachen. Later on at Karlsruhe I was the head of the computing center, which was a very small one. There was nothing special about that, since there was a very small group to assist me. It's not to be compared with a computing center as it is now. But in Erlangen as well I had formed a full-time connection with the computing people.

Analog and digital computers; publications

Nebeker:

Did you continue to use computers in your research?

Schuessler:

Yes. It started very early. Already in Aachen we did that. That was another rather first, early connection to signal processing at this time—digital signal processing. We can talk about that.

Nebeker:

Yes, I'd very much like to hear about that. Maybe the way to do this is to look at your publications.

Schuessler:

The very first application was about simulating or investigating transfer functions on an analog computer. It was my connection to that. A point which might be of interest is the following: The structures that you use for simulating transfer functions on an analog computer are precisely the same as you use for digital signal processing. The difference is that in the case of an analog computer you have just an integrator as the basic element. In DSP you have the delay element. In addition you need multipliers. In an analog case it's just a potentiometer; in the other case, it is a multiplier, a digital multiplier. The summation is done just with the integrated circuit—the integrator—it can be done easily: the structure is just the same. All the structures we have, we know for example the cascade structures, things like that, can be done and have been done, and I did it, back in the late '50s with analog means.

Nebeker:

What was the context of that work? Why were you looking at these transfer functions?

Schuessler:

I made these just for fun. My supervisor, Professor Ashov, gave me the freedom to work on that.

Nebeker:

Wasn't it an immediate application?

Schuessler:

No, I think that's true in general for the things I did over my whole career. Very rarely was there an immediate application. In most cases it was just an idea, and it was sometimes impossible to get somebody out of industry interested in that, but that's another story.

Nebeker:

How did you get onto these topics? Is it because it was mathematically or scientifically interesting?

Schuessler:

I was just interested in the transient behavior of circuits and the like.

Nebeker:

Not because these were problems that the communications engineers were grappling with?

Schuessler:

No, no. Later on, I was interested just by myself, not by questions of industry, in finding filters the transient responses of which are usable for data transmission. It means that the impulse response in a channel of limited bandwidth should be rather short, or finding the distance so that the product of impulse duration and bandwidth is a minimum in a practical demonstration.

Nebeker:

Were you thinking of transfer in this work?

Schuessler:

Yes. The application. Not an actual one, but just the application. The possible one we had in mind was just this question and to use the analog computer just to play with the potentiometers, shifting the poles and zeros around and looking at the impulse responses. We finally found as a hypothesis that the minimum will be achieved if the frequency response in the stop-band is of Chebyshev behavior, and the impulse response in the time domain dies out in a Chebyshev way as well, somewhat like this.

Nebeker:

Empirically determined?

Schuessler:

Empirically. We could not prove it, but we found very good results just by playing with the analog computer. Again this hypothesis—not more—was a starting point for designing filters of this type on the digital computer.

Nebeker:

Why did you move to a digital computer?

Schuessler:

Well, finding let's say hundreds of examples just by playing around is one possibility, but it's not satisfying. In this case we have just the general rule, and developing the program to do that under certain constraints is by far better. And later on, after we published the results, were told that these circuits have been used in practice, which is somehow satisfying. By the way, a report about that has been published in the 1965 IEEE Transactions on Circuit Theory.

Nebeker:

Number thirteen on this list of publications.

Schuessler:

All the others have been published in German. Sorry, but it is the case. Later on we thought that this might be nice to publish that in English as well.

Nebeker:

In recent years has more of your work been published in English because there is more of an international community?

Schuessler:

That started, to a large extent, during the year I spent at Cornell University. I came in contact with people and saw that it was possible for me to write something in English that would be accepted.

Digital filters, FIR systems

Nebeker:

On to your great involvement with computers. I've heard the story that it was to simulate some of these physical filters that the digital computer was first used at Lincoln Labs. Are you saying that you moved from analog simulation of these to digital because you could make a fuller study of the response behaviors?

Schuessler:

The design as well. These impulse-forming circuits have been designed. It means we found not only the poles and zeros but the circuitry as well. We did that on a computer, and my very first three or four Ph.D. candidates did that for their theses.

Nebeker:

This was an early publication?

Schuessler:

- Audio File

- MP3 Audio

(335 - schuessler - clip 1.mp3)

That was an early publication. It is not about digital signal processing but there's a close connection. I can say a little bit about that. Pretty early on I was interested in system theory, the description of systems in the frequency domain as well as in the time domain. I was very much influenced by the work by Karl Kupfmuller.

He was the man who invented the term system theory, and his very early investigations in the early '20s about the behavior of analog circuits described the frequency of mean as an ideal low pass with oscillating amplitude but linear phase. Also looking at the behavior in the time domain at the impulse response and the step response. This is the basis of the so-called basic law for communication—how much can you get through a channel, etc. And a description of a general channel which came out of this theory was nothing else but a delay line. Imagine a line of delaying elements, and a couple of them differently delayed. One just multiplies with a coefficient and adds the whole thing up. There is nothing else but the implementation of a system having, generally speaking, a frequency response to be expressed as the sum of a cosine or sine function.

It is nothing else but in our current terms an FIR filter. But the idea, this old idea—which has practical use by the way as an equalizer and has been used in practice—this basic idea was done in the continuous domain, was not only investigated but really built in the continuous domain. Just for fun, we built that in Aachen as well. Really using delay elements consisting of continuous low passes, and the multiplier was put in potentiometers, as we talked about before. This rather early paper was nothing else but this structure, this delaying element and the potentiometers at the summation of the whole thing. Here was a non-causal representation. Here was the causal implementation, and the whole thing has been done by summing amplifiers here.

Here you see an expression of this type, but you see here it's nothing else but a representation of any band-limited function by a sequence of sine x over x functions, according to sampling theory, requiring an ideal low pass. Of this ideal low pass we approximated. That's the magnitude response and the delay should be constant—it's almost constant. That's the impulse response—better. That's the step response, pretty close to sine x over x. We played around with that, and ended up with quite a few different results. For example, with this we of course get a frequency response of that type, but we can change that. It was an impulse response to the step response, and we could find differentiators.

For example here—that's a step response, and the differential quotient of that. Things like that could be done, or we could do the summation over a rectangular grid, or we could do the Hilbert transformation. This set of coefficients is nothing else but the impulse response of the special FIR system with linear phase. And that was in fact my first playing around with the structures, which we now know as the digital factors of digital processing systems.

Nebeker:

That was in 1963?

Schuessler:

It was published in 1963. At that time I was at Cornell. That means the work has been done in ‘61 or ‘62.

Nebeker:

Had you encountered any other work on digital filters yourself?

Schuessler:

No. At that time I didn't even know the word. And I think that was true more or less everywhere.

Nebeker:

Were you influenced by people at MIT or Bell Labs, where they may have been doing something?

Schuessler:

No. It came a little bit later. There was this connection with the people at Cornell, where, by the way, I gave a lecture and talked about analog computers and their use. But there was nothing about digital filtering at all. But back in Germany in ‘64 we published a paper on the calculation of the impulse response of continuous networks by using the z-transformation. And that's just the type of work which has been done more or less at the same time at Bell Labs by Jim Kaiser. At that time they had a much larger program to simulate continuous systems on a digital computer, calculating the impulse response and all that. But we were at least following the same idea. And what we did was, starting with a cascade connection of differences, we transformed this continuous system of second order or so into a digital one. And then we are in what we call now the IIR domain. All these things have been done using the z-transformation and we ended up with transfer functions in the z-domain.

Nebeker:

I think it's not a problem.

Schuessler:

That was my first connection to digital filters, back in ‘65.

Nebeker:

You had two articles there. Was this a separate project?

Schuessler:

This was the first one I was talking about before, where we built this FIR system, this analog version of the FIR system.

Nebeker:

What did you see as the value of the digital filter work that you were doing?

Schuessler:

Well, at that time we did not work on digital filters. What we did was the simulation of continuous systems, such that we could look at the time response.

Nebeker:

You simulated them digitally.

Schuessler:

Yes, that's right.

Nebeker:

Were you thinking of this as a way of better analyzing filters?

Schuessler:

Well, the transition to digital filters was smooth. That means we started rather early to use the analog version of digital filters. What I mean is sampling elements—the delay element we have in digital filters is done such that an impulse signal, in the time domain, is sampled, and the values are stored in a capacitor for a certain time, and then again sampled and shifted, and things like that. In effect, we built these analog versions of digital filters at that time.

Nebeker:

There must have been some point when people realized that it's not digital. It wasn’t done digitally in order to analyze or improve analog circuits, but to do things digitally.

Schuessler:

Very early we had the idea we had to build it: not only to simulate it on a computer, we have to build it. This is a paper from that time published in English for Proceedings of the IEEE as a letter.

Nebeker:

In 1968?

Schuessler:

That's a circuit we used. The title was "A New Sample and Hold Device and its Application to the Realization of Digital Filters." Digital filters—it's funny! But anyway, here you see the structure that had been built. It is a cascade structure with these blocks, and delay sample-and-hold elements. Here is the impulse response of an elliptic filter of the fourth order, and a change of the frequency band can be done easily just by changing the sampling frequency. Here you see three different versions. It was published by my Ph.D. student at the time. He already had his Ph.D., I think, when he did that. Anyway, he invented this circuit.

Nebeker:

This, then, does not appear on your list of publications?

Schuessler:

There's been a larger paper about the same thing, where I talk about the sample-and-hold analog computer. Perhaps that's more precise, an article by Walter Kuntz as well. There is more on it here. The basic idea was published in the Proceedings at that time.

Research support and collaborations; Arden House workshops

Schuessler:

In ‘68 I was in contact with Jim Kaiser; I was again in the United States for three months at Bell Labs in Merrimack Valley, and at that time the student visitors as well as visiting professors were invited to come to Murray Hill for a two-day visit. I used that visit as an opportunity to meet Jim Kaiser.

Nebeker:

You had read of his work?

Schuessler:

I read it, and some of the friends I had at Cornell had a stronger connection to him, so I was to some extent introduced to Jim Kaiser. The next step was my inviting Jim Kaiser to come over to Erlangen, and he came in January. At that time we demonstrated a couple of things we did, including the design of digital filters and FIR systems. One of my students worked on the design of FII Hilbert transformers, especially with change of behavior. We showed him that. Out of this came an invitation for me to attend the next Arden House workshop in January of 1970. It was the second workshop. The first one concerned FFT work and Tukey. There I presented our work on the design of FIR filters, linear phase, and change of behavior of the frequency response. What we presented there was a system which has been called the extra ripple filter. The whole thing was a starting point for a large number of investigations, especially an algorithm found by Parks and McClellan, the very famous Parks-McClellan Exchange Algorithm for designing just this type of filter.

Nebeker:

How was your work guided in those years?

Schuessler:

Through contacts with American colleagues. Nothing else.

Nebeker:

So it wasn't that a particular circuit was needed for this or that?

Schuessler:

We tried to understand things, and we tried to get support. We could not get any support from industry.

Nebeker:

Did you try going to industry?

Schuessler:

Yes. I made quite a few presentations, talked about them about how nice it was.

Nebeker:

Was it the communications industry you tried to interest in it?

Schuessler:

Yes, it was. They were not at all interested, and they said, "It will never work!" It's the same thing we heard this morning. Well, work had to come out of the United States for them to believe it possible. We didn't have a chance. But we had a chance with Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, a German research association. We got more or less all our support from them.

Nebeker:

That's a governmental support, like NSF?

Schuessler:

Yes. It works just the same as the National Science Foundation. The German version of the NSF, so to speak, is very good. Excellent.

Nebeker:

They were the main supporters of your research?

Schuessler:

Yes, of all the research, and quite a few of my Ph.D. students.

Nebeker:

Was it difficult to convince them that this was important?

Schuessler:

Not really. We managed to convince them, and later on, around 1975, I was a member of the DFG senate and I managed to get what is called “general support” for this type of research. Not only for us, of course.

Nebeker:

For the field?

Schuessler:

For the field, and this way other institutes, other universities, became interested in the topic. We met every year to report our results, and the whole thing grew.

Nebeker:

From your Cornell days onward, did you continue to go to international conferences and publish internationally?

Schuessler:

Yes, there were only two more Arden House conferences, in 1972 and 1974. There were no more after that. I didn’t attend the first ICASSP in 1976, but I later on I went to quite a few SSP conferences as well as the conferences of the IEEE Circuits and Systems Society. I didn’t attend all, but I went to quite a few.

Nebeker:

I talked with Bede Liu at Princeton University recently, and he told me that he was at one point president of the Circuits and Systems Society. He said that he made the proposal that the organization be circuit signals and systems and wanted to bring signal processing into that society. Of course there's a real overlap, but we now know what happened was that signal processing went to acoustics.

Schuessler:

This was to a large extent the work of Larry Rabiner. I'm pretty sure about that. He was, as far as I recall, one of the first presidents, and I think he founded ICASSP. I think he was the president of the Society when the first conference was held in 1976. I recall something about that. Starting with the first Arden House Conference, I had just contacted the people and the other groups in Germany and committees that would support the exchange. The first one I got was Tom Parks. Tom Parks was, by the way, my first and only graduate student at Cornell. He did his master's thesis with me. I convinced him that he should come to Erlangen and he spent a year with us, and later on Sid Burrus was with us twice for a year and there was as well a couple of others who came over for a year. I have been to the States again for some months at MIT with Alan Oppenheim and at Rice University for a couple of months.

Nebeker:

There's been good contact and exchange?

Schuessler:

It was excellent. I hope they enjoyed it. We certainly did.

Digital signal processing and speech processing in Germany

Nebeker:

Were there other groups in Germany in digital signal processing during those years?

Schuessler:

Yes. Very early Alfred Fettweis started this idea to transform an analog selective system into a wave-digital filter and to obtain just a digital filter. The main point is that in that case the starting point is and has to be an analog filter. But the knowledge about the design of analog selective systems is more or less gone. And that's why he did not have much success in the States, as far as I see it. Well, there are places where he had success, where they believed him, but I don't think that the wave-digital filter approach has come through. This may be impolite to say, but it is my impression. He has a paper about that for example. By the way, this might be different in the Circuits and Systems Society. They are still coming more from analog circuitry to the digital one. But that is another story.

Nebeker:

Does it seem to you, in looking back, that it was the logical and better thing to do, to have the signal processing in with the electro-acoustics people rather than the circuits and systems ones?

Schuessler:

Probably not. The essential point was that the first people who used digital signal processing had been those who had to transmit speech.

Nebeker:

The speech-processing people?

Schuessler:

Yes. I think that was the reason that the people at Bell Labs—this group of Flanagan's—became interested in signal processing as such, since they saw a chance to improve the speech-processing business, to transmit speech with higher efficiency. Really a very important point was that this group—these people under Flanagan, Larry Rabiner especially—had the time and support to push the whole area. They did a lot of groundbreaking work, no doubt about that.

Nebeker:

I talked to Jim Flanagan recently, and got an account of his work.

Schuessler:

I tried to “advertise” signal processing in Germany, and maybe to some extent in Europe. I attended, for example, the conferences in London that were fairly early conferences, with our very first one, the first one in Germany in ‘73. The result was somewhat distributed throughout Germany as well. But there are still universities in Germany where signal processing is not a topic—no lectures about it, as far as I know.

Nebeker:

Were you not thinking of speech processing tasks in your work?

Schuessler:

Not I myself, but one of my Ph.D. students. After finishing his Ph.D., he was still a member of the Institute and started to work on speech processing. I told him he should do that. I said, "Well, it might be nice if we have a seminar, and would you please prepare a seminar on speech processing?" He did, and then I told him, "Well, it might be nice if you give a lecture about it." Anyway, he became interested in that while he was professor in Keach. It's just one possibility.

Then I had a colleague who came from Frankfurt to Erlangen and spent ten years with us before he died, by far too young. Anyway, he worked on speech processing. Answering your question directly, I myself did not work on speech processing but people at the Institute, the people in my neighborhood so to speak, worked on speech processing. One point might be of interest: since all the people in Germany in industry told me that it would never work, we started early to build signal processors and digital filters with whatever means we had at that time. We used these programmable means to do speech processing. If they say that Ben Gold who did that with FDP, well, it was somewhat later. We could do that in an earlier time, very early, with homemade multipliers. Imagine that!

Nebeker:

Did you succeed in gaining the interest of the communications industry in Germany?

Schuessler:

No, no. They said, "Well, it's a nice example, yes, might become interesting somewhere, sometime." They also probably said, "This Schuessler doesn't know what to do, how to make really interesting things. He is just playing around."

Seismic applications

Nebeker:

Were there any other applications areas that you or your students moved into?

Schuessler:

We looked into seismic applications. Again, there was somebody else who did his Ph.D. with me, and is still working with us, and is on the committee of this conference. He is still interested in seismic problems. I became somewhat interested in them myself, and that started a connection with another one who was with us for a year, Mike Ekstrom, who was with Schlumberger, and they got some connection with Schlumberger. In the beginning he was in California and not with Schlumberger. During that time he spent a year with us, and he later went to Schlumberger and was in Paris for quite a long time. I was invited there, and was a member of a committee who investigated different things there.

Nebeker:

What exactly were this fellow and your student trying to do with seismic signals?

Schuessler:

Many different things. There is a lab somehow connected to the university, and there have been some connections there in the interpretation of their results. As far as Schlumberger is concerned, it was just a measurement they made, investigating the results. They are looking for oil, of course.

Nebeker:

Were they building digital seismographs?

Schuessler:

Yes, for measuring the results.

Nebeker:

Were they digitizing the signal and analyzing it?

Schuessler:

Yes, to digitalize the signal and analyze it. I was told at the time that the people with the highest use of computers were those who were looking for oil.

Nebeker:

That's how Texas Instruments got started.

Schuessler:

They had enough money.

Digital signal processing and filters publications

Nebeker:

Perhaps we should look again at your publication list.

Schuessler:

Maybe something else might be of interest. We heard this morning that the first really important book about the field was written by Gold and Rader. This is the second book.

Nebeker:

This is the second book on digital signal processing?

Schuessler:

Yes, published in Germany in 1973. It was sold out pretty soon but was never translated into English. There were plans to do so when it first came out, but it was my fault that I didn't push it. Later on I didn't have the time to get a newer edition. Meanwhile the next edition was in ‘88.

Nebeker:

Were you trying to sum up the field at that point?

Schuessler:

That was the point, that's right.

Nebeker:

Was this well received in Germany?

Schuessler:

Yes. It sold out, as I said, pretty soon. But I didn't allow them to make a reprint saying, "Well, I have to change some words.” I never did. I never did it in time. Later on I rewrote it completely, but it took some time.

Nebeker:

This must have been influential in the German picture in signal processing.

Schuessler:

I think so. I hope so. But I don't claim that this influenced anything else. Two years later the books by Oppenheim and Schafer came out, and those authored by Gold and Rabiner, and of course they had really worldwide influence, no doubt about that. A year ago I had to prepare some notes on some early contributions to signal processing by members of our Institute. You might be interested in that.

Nebeker:

Perhaps you could summarize what areas and briefly what work was done?

Schuessler:

- Audio File

- MP3 Audio

(335 - schuessler - clip 2.mp3)

Some of the things we’ve already talked about. The first one was this design of non-recursive Hilbert transformers with Chebyshev approximation, and imaginary frequency response, by Otto Herrmann. This is referring to a list of publications that should be included here somewhere. Then, design of linear phase non-recursive system with Chebyshev approximation of the ideal low pass filter. That was the thing I presented at the Arden House workshop; we talked about that. And the design of minimum phase FIR low passes. Again presented at the same Arden House conference, then the design and implementation of analog digital filters. Here I mention the analog version of digital filters; we built the sample-and-hold devices already in ‘70—FIR digital filter built with blocks of second order with three homemade serial parallel multipliers.

By the way, this here, especially this one, it was influenced by the multipliers they had built at Bell Labs. And this was a work published by Jim Kaiser, Leland Jackson, and Henry McDonald. It was a paper about building a digital filter, and that influenced our work, no doubt about that. For example, especially this multiplier with a clock frequency, we can see, of 320 kilohertz. We built an FIR filter and later on an IIR filter with at most a 32 second-degree with cascade or parallel structure. That was a non-recursive filter—this one here was a recursive one. We used it for examining all different things. We used it in the lab as well. We had an early lab on signal processing for our students.

Nebeker:

Was it taught as something in its own right, not as a means of achieving some other thing?

Schuessler:

Yes. There is a long tradition in Germany in the design of analog filters. The whole thing started very early, already in the ‘30s, perhaps earlier, in the late ‘20s. This was work done by Cauer. You might have heard of him. He died in Berlin in the very last hours of WWII, killed by the Russians. He was a famous filter man, and he was the first one who found these elliptic filters. You might have heard of his work.

Nebeker:

What was the context of that work?

Schuessler:

Nothing about digital filters. Nothing digital at all at that time.

Nebeker:

Why was he interested in filters?

Schuessler:

For telecommunication purposes. It’s the type of filter which was used over and over everywhere. He himself was a mathematician, and he published a very famous book on the theory of linear systems which was translated into English in later years. I forgot when this was. We named the street Cauerstrasse after him. He was a great man. Of course I never met him because at the end of war I was seventeen years old.

Nebeker:

Could I get photocopies of these things when you have a chance?

Schuessler:

Well, you can take it with you. Maybe you’ll return it sometime.

Nebeker:

I will certainly do that. Could we, for our photo collection, make copies of these prints?

Schuessler:

Yes, of course. Maybe I should mention this. A year ago, I was asked by Ron Schafer about just such a contribution. At the last ICASSP in Atlanta, Ron Schafer gave a talk about the history of the DSP, and he was kind enough to ask me for some comments, and I provided this and used it. Anyway, that's why I still have that.

Nebeker:

I'm glad you did that.

Schuessler:

These are the filters, the first ones we built. I'm pretty sure it was the first one in Europe.

Nebeker:

It would be good for us to have copies of that.

Research support; graduate student research and applications

Schuessler:

We became somewhat interested in the connection to applications. For example, in some very few cases in connection with industry, for example—partly by former students of mine, who went to industry with their interests and they brought this knowledge into different places and we had some connections.

Nebeker:

What application areas were those?

Schuessler:

Medical signal processing, processing of X-rays, for example X-ray pictures. It is one of the things we still have some contact with, but the main point is that my former students still have contact with the Institute and with myself.

Nebeker:

It must be gratifying to see these ideas used in different areas.

Schuessler:

Yes, that's right. It was true with Philips Communication Industry in Nuremberg, which now belongs to Lucent Technologies, by the way, and some others for example. Vary, a former Ph.D. student of mine, did speech coding for the mobile telephone at his company, the PKI. Meanwhile he is a professor in Aachen.

One other interesting point was in cooperation with the German Telecom, well, it's now called the Telecom. They had and still have a research institute, and in connection with them we built firstly a simulator for the mobile radio channel, and secondly a device for measuring the properties of this channel.

Nebeker:

That was a digital simulator?

Schuessler:

- Audio File

- MP3 Audio

(335 - schuessler - clip 3.mp3)

A digital simulator which was used in Paris. At that time different countries and different companies in Europe designed devices for doing the mobile communication, and the question was what should be used, which one it would select. They did the selection process under fair circumstances, and by fair means. Instead of moving around the country and having to deal with changing transmission conditions, they did the testing in the lab with our simulator. The idea was that it must be possible to do all the different simulations of the trends digitally.

But of course it means that the original signal, which is in the range of gigahertz, has to be brought down in the range where our simulator could work, and that was a frequency range of only up to a couple of megahertz. It was possible to do it, but we had to cooperate with a company who did this down-modulation, up-modulation business, and the simulating work itself, with randomly varying parameters, we did ourselves. It was a very nice, instructional problem.

Nebeker:

You have had a very large number of graduate students.

Schuessler:

Forty-eight, to be precise. Forty-eight Ph.D.s, and six people who did Habilitation with me. I just look for the simulator—here it is: the digital frequency-selective fading simulator. We published that in 1989. And later on this device for measuring the behavior of the channel in practice, we have quite a few papers on that. Here, the system for measuring the properties of mobile radio channels is just one of these.

Nebeker:

Was that work important in the introduction to mobile telephony?

Schuessler:

Yes, we have been told that.

Nebeker:

Your simulator was used?

Schuessler:

It was used. Well, the European telecom companies did it as I said. Today they are more modern simulators. This one was built more than ten years ago with equipment we had at that time. It would be earlier. We built a parallel computer. Imagine that.

Nebeker:

Parallel processing?

Schuessler:

Yes, with four processing elements. This was published in the Proceedings of the IEEE back in ‘87. "A Modern Processor for Signal Processing." We had the close cooperation of people in computer science at that time. MUPSI (multi-processor for simulation) was the name.

Nebeker:

Did you have an application in mind for this?

Schuessler:

No. No. Just for fun.

Nebeker:

Is it that you realized that it should be possible to do parallel processing with some of these?

Schuessler:

Yes. We were supported again by the DFG, the research association.

Nebeker:

I take it you believe that they have been forward-looking and wise in their support of research?

Schuessler:

Yes. They have been very good in this respect. Not only for us of course. They supported research since the 1920s already and were re-founded after the war. Since then they are doing this supporting work. They do it very nicely and it's really excellent. I know it from the inside.

Teaching

Nebeker:

What haven't we talked about in your own work? Are there areas that we haven't talked about?

Schuessler:

Well of course I had teaching. Loads. For more than twenty years I also had to teach basic electrical engineering classes. Every second year I had to give a course on system theory for all the electrical engineers in Erlangen. I had to give courses on communication. After all that, I had a course on digital signal processing.

Nebeker:

What was a typical number of courses in a year for you?

Schuessler:

The official load for a German professor is eight hours teaching per week. That means in the range of three to four different courses. But I really came to that point and sometimes a little bit more. It's not as severe as it sounds. Usually the seminars I included as well, and the supervising.

Nebeker:

You get some credit for that?

Schuessler:

Professors get credit for that as well. But I had a pretty large load. It was the main reason why I did not publish a second edition of this book earlier since instead I wrote two books about network analysis. This is basic electrical engineering, you know. It took time. The longest course at that time we had in the range of 300 to 350 students in the beginning of the year. That was something.

Evolution of the digital signal processing field

Nebeker:

I wanted to ask about how the field looks to you. I suppose in the ‘60s Bell Labs and MIT were obvious places of important work?

Schuessler:

Yes.

Nebeker:

Has the United States continued to dominate, or is it much more spread around now?

Schuessler:

My impression is that the United States dominates the field—that the distance between the United States and all the others has increased.

Nebeker:

Is that right?

Schuessler:

It has increased over the last twenty-five years. You might want to look at the collected papers on DSP published in the ‘70s.

Nebeker:

Yes, I've seen that.

Schuessler:

I have been rather proud that quite a few of our papers are included there. If the same thing is done now, I don't think we would get any big part anymore. There is a book that will be published soon about FFT, as far as I have heard about it. The distance is, as far as I see it, larger now.

Nebeker:

What's the explanation for that? There are many areas of science and technology where, you know, after World War II the United States had a much clearer lead than it does now.

Schuessler:

If I look at it from a point of view of universities, the main point is that in the United States probably every technical university has signal processing as a main part in the curriculum. This morning I listened to this special section on DSP in education, and there was a special session organized by somebody, and he said, "Well, we have only contributions out of the United States. Maybe I didn't look carefully enough, but we couldn't find anyone in Europe to talk about this subject." Anyway, five contributions came out of United States, and I think they said in the very beginning that every university in the United States has courses in DSP, no doubt about that. The United States has a larger number—by far larger than Europe—of universities. That's one reason for the difference. Of course the whole thing is influenced by the interest of the industry in the field.

Nebeker:

Is it the case in Germany that there are electrical engineering departments that don't teach DSP?

Schuessler:

As far as I know, yes. They might talk about special applications or talk about fields where DSP is used, somehow used as a background, but teaching signal processing just for itself, that’s not done.

Before we talked about design of analog filters, and talked about Cauer. There was a tradition in that field in Germany. Besides Cauer there had been two others, Piloty in Munich, and Bader in Stuttgart. And their followers, so to speak, Saal in Munich later on, and another one, a former student of Bader was Unbhauen, who came to Erlangen. And at least at these two places, in Stuttgart, and then in Munich, and in Erlangen, the design of analog filters was done, let's say, up to now. And these are the places where filters are designed—analog filters have been designed—under the belief they will be used forever.

I recall, just to give you an American example, there have been people like Guillemin at MIT. In one of his books you can find that Guillemin said to his students, "Network theory is your bread and butter. Not only the butter, but the bread too." It was the general belief of the electrical engineers at that time. That time is over.

Nebeker:

I had heard of some of those German engineers, and I don't know much of that history at all. Bell Labs did early work in analog filters.

Schuessler:

I'll give you an example of that. In the time after the war, the knowledge about continuous filters - it is a bit much if I say it was concentrated in Germany - but to some extent it's true. At that time the state of knowledge here was really pretty high, and at that time catalogs were generated and published with just elliptic filters. One could just take the elements, or the numbers for the coils and capacitors out of this catalog.

This catalog was published by Saal. He was supported by industry, by the way. At that time he was not a professor. He was just a member of AEG. These catalogs were distributed in the States as well, and Saal is very well known in the United States. He had a heavily cited paper back in the ‘50s. Rudolph Saal. Recently he got the highest teaching award from the IEEE.

Nebeker:

Has your work had any connection with the control systems?

Schuessler:

Short answer: no. But I'm interested in it. Of course I know people working in the field, but I think I should say no. Now I'm writing the second volume of my first book. As I said, another edition came out in ‘88 and the last version so far came out in ‘94. The second volume is still under preparation.

The point is that I put method programs in all the different sections of the book and, well, that takes time, but I hope that it helps. By the way, we were very early in providing signal processing lab courses for students: first with homemade processors, and later on with the computer using a homemade language. For the last six or eight years, we have been using MATLAB. I found MATLAB, by the way, at the ICASSP in Dallas just ten years ago. I saw it there, bought it immediately, and since then we have been using it.

Nebeker:

I wonder if you have any comments about the way we have divided the development of signal processing? What we were looking at mainly was the Professional Group on Audio, and then audio and electro-acoustics and then you know it became SSP and then SPS later on.

Schuessler:

This part here?

Nebeker:

The first part is the audio and electro-acoustics, and then here in the ‘60s we get into the digital signal processing.

Schuessler:

Well, the FFT was the basic step forward. No doubt about that. That's true. And as it was mentioned this morning, this work by Gold and Rader was another step. Of large influence was as well one chapter in a book, edited by Kaiser and Kuo and published in 1966 by Wiley, even earlier than the book by Gold and Rader. Chapter seven in that book, written by Jim Kaiser, was on the design of digital filters.

Nebeker:

That was very influential?

Schuessler:

Once upon a time it was very important and very good, and it's why I recall it shortly before the book by Gold and Rader was published. Just this one chapter, you know, but it was very worthwhile, the early ‘70s and the early ‘80s. That was the Lincoln Labs signal processor. In ‘83, Texas Instruments came out with their first signal processor, the 32010. By the way, we used all these signal processors ourselves later on. Computer music I don't know anything about. Well, there was a contribution very early by somebody out of Bell Labs.

IEEE

Nebeker:

I am particularly interested in the history of the Society. Maybe you can tell me the history of your IEEE involvement.

Schuessler:

I became a member of the IEEE during my time at Cornell. This means after ‘63, and in connection with the early work on DSP. I became a Fellow of IEEE. It must be roughly twenty years ago or so.

Nebeker:

You became a fellow in ‘77.

Schuessler:

‘77. Twenty years ago, as I said. It was in ‘79 that I got the Society award.

Nebeker:

Did you join the Professional Group on Audio, or maybe it was audio and electroacoustics?

Schuessler:

I think I joined there. It was at that time, as I told you, I was interested in network theory, filter design business, which was rather important.

Nebeker:

It became the Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing Society in 1974. "Signal processing" was put into the name in ‘74.

Schuessler:

Yes, yes. Well, as I already said, that was due to the influence of Larry Rabiner. I'm pretty sure about that.

Nebeker:

Did you join the society shortly thereafter?

Schuessler:

Well, I got the Proceedings, and the Transactions anyway.

Nebeker:

Then you must have joined.

Schuessler:

Yes. And I got the Transactions of the IEEE Circuit and Systems Society as well.

Nebeker:

That means you were a member of that society as well.

Schuessler:

It doesn't matter, since I am, so to speak, in both societies.

Nebeker:

Has that been a problem, the fact that there is a big overlap between those societies?

Schuessler:

Well, sometimes I notice it, and I have been told that there is some friction, so to speak. But I cannot say anything about the details. I just don't know.

Nebeker:

But in your own experience, is it troublesome to have to look in two places?

Schuessler:

No, no, it doesn't matter. Usually the people, at least the colleagues I know, look into both Transactions. Now they have two Transactions in the Circuits and Systems Society, but sometimes they miss important papers which are in the other section. It happens.

Nebeker:

It would be good to know if in your view there was a better way of technical organization within the IEEE.

Schuessler:

I cannot say anything about that. I am not close enough to have my own opinion. At most I can say about things I have heard, but that's not useful. I’d like to mention that I had and still have good contact with quite a few people out of the old times of signal processing, especially Americans. I already mentioned a couple of names. Quite a few of them have been in Erlangen, including Al Oppenheim. I know Ben Gold and Charlie Rader quite well, of course. I mentioned Sanjit Mitra.

Nebeker:

I talked with him.

Schuessler:

We had been colleagues at Cornell back in ‘62 and ‘63.

Nebeker:

Is that right?

Schuessler:

And then in total he spent a year with us in Erlangen.

Nebeker:

Is that right?

Schuessler:

The last time last year, the last three months, and all that supported by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation in Germany. I already mentioned Mike Ekstrom, who is a close friend. I mentioned already Sid Burrus, who spent more than two years with us. Within the last two weeks he was in Erlangen again.

Nebeker:

It's wonderful that there is such interaction.

Schuessler:

Ron Schafer was with us only for a few days, but anyway we had contact with him and others in Atlanta as well. Well, we know each other. One result of this cooperation was this book we published in ‘94 by Prentice-Hall called Computer-Based Exercises for Signal Processing. We did this with five American colleagues, including Burrus, Ron Schafer, Jim McClellan, Oppenheim, Parks, and myself.

Nebeker:

Has that book been well received?

Schuessler:

It's a book for students. Last night, Tom Robbins of Prentice-Hall told me that it has sold pretty well. They are now bringing out an updated version. They just updated the method programs we are citing in that book. I mention it only as a sign of cooperation between American friends and myself.

Definition of signal processing as a field

Nebeker:

What's your view of signal processing as an intellectual field? Is there a core of theory, or is this a bunch of techniques that are similar because you are doing something with a signal but lacking a theoretical core?

Schuessler:

Well, for me the theoretical core was and still is the essential point. As an engineer, I am lucky that all of this can be applied. The influence is to be seen not only in industrial regions, but for the public as well. The first application was the compact disc for music. It was done already fifteen years ago, somewhat more. As an engineer I am glad about that. But the main reason for me to be interested and to still work on signal processing is just the intellectual core of it.

Nebeker:

If there weren't these applications, would you see a field there that is of interest?

Schuessler:

Yes, of great interest. This morning it was mentioned that it is not just a field for communication engineers; it should be a field for all engineers or even for all physicists or for all scientists who are doing measurements. They can use it, and, in fact, they use it already for processing without knowing DSP. Just for processing method data.

Nebeker:

It's amazing that it's becoming so universal.

Schuessler:

Nebeker:

Yes, thank you very much.