IEEE Circuits and Systems Society History

Brief Timeline

According to John Brainerd writing in the December 1983 centennial issue of the Circuits and Systems Magazine, by about 1948 or 1949, an existing informal group or subcommittee interested in Circuit Theory saw a possiblity of having a group for itself, because the concept of Professional Groups in IRE had arisen.

On 5 April 1949 the IRE Board approved a petition signed by 26 IRE members to form the IRE Circuit Theory Group.

March 20, 1951 - First meeting of the IRE Professional Group on Circuit Theory. The first issue of the Transactions, PGCT-1, was dated December 1952. It refers to a Newsletter for members but no copy of the original issue has been found.

March 25, 1963 - Name change to IEEE Professional Technical Group on Circuit Theory

1966 - Became Group on Circuit Theory

In 1971 the opportunity to gain greater independence by a change from Group to Society status arose, and the IEEE Board of Directors approved the change in May 1972. Later that year (December 1972) the Board approved the change in name to Circuits and Systems Society. This data comes from a History of the Society written by Ban Leon (in the CAS Magazine Centennial Issue), and differs from another claim (below) that the name change was in November. This should be easy toi resolve from the minutes of the IEEE Board of Directors

November 2, 1972 - Name change to IEEE Circuits and Systems Society.

Past Presidents

| Date | Name | Affiliation |

| 1952 - 1953 | John G. Brainerd | University of Pennsylvania |

| 1954 - 1955 | Robert L. Dietzold | Bell Labs |

| 1955 | Chester H. Page | National Bureau of Standards |

| 1956 - 1957 | Herbert J. Carlin | Polytech. Inst. of Brooklyn, Brooklyn, NY |

| 1958 - 1959 | William H. Huggins | Westinghouse Electric Corp. |

| 1960 - 1961 | Sidney Darlington | Bell Labs |

| 1962 - 1963 | James H. Mulligan | New York University |

| 1964 - 31 Mar 1965 | Ralph J. Schwarz | Columbia University |

| 1 Apr 1965 - 31 Mar 1966 | John. G. Linvill | Stanford University |

| 1 Apr 1966 - 31 Dec 1966 | M.E. Van Valkenburg | University of Illinois, Urbana, IL |

| 1967 | Franklin H. Blecher | Bell Labs |

| 1968 - 1969 | Arthur P. Stern | The Magnavox Company |

| 1970 - 1971 | Benjamin J. Leon | Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN |

| 1972 | Ernest S. Kuh | University of California, Berkeley, CA |

| 1973 | M.R. Aaron | Bell Labs |

| 1974 | Sydney R. Parker | Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA |

| 1975 | Belle A. Shenoi | Wright State University, Dayton, OH |

| 1976 | Mohammed Ghausi | Wayne State University, Detroit, MI |

| 1977 | Leon O. Chua | University of California, Berkeley, CA |

| 1978 | Omar Wing | Columbia University, New York, NY |

| 1979 | Timothy N. Trick | University of Illinois, Urbana, IL |

| 1980 | Carl F. Kurth | Bell Labs |

| 1981 | Stephen W. Director | Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA |

| 1982 | Bede Liu | Princeton University, Princeton, NJ |

| 1983 | Kenneth R. Laker | University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA |

| 1984 | Alan N. Willson Jr. | University of California, Los Angeles, CA |

| 1985 | W. Kenneth Jenkins | University of Illinois, Urbana, IL |

| 1986 | Sanjit K. Mitra | University of California, Santa Barbara, CA |

| 1987 | Ronald A. Rohrer | Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA |

| 1988 | Ming Liou | Bell Labs |

| 1989 | Anthony N. Michel | Notre Dame University, Notre Dame, IN |

| 1990 | Rolf Schaumann | University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN |

| 1991 | Sung Mo Kang | University of Illinois, Urbana, IL |

| 1992 | Randall L. Geiger | Texas A & M University, College Station, TX |

| 1993 | Philip V. Lopresti | AT & T |

| 1994 | Wai-Kai Chen | University of Illinois, Chicago, IL |

| 1995 | Ruey-Wen Liu | University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN |

| 1996 | Michael R. Lightner | University of Colorado, Boulder, CO |

| 1997 | John Choma Jr. | Univ. of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA |

| 1998 | Rui J.P. de Figureido | University of California, Irvine, CA |

| 1999 | George S. Moschytz | Swiss Federal Inst. of Tech, Zurich, Switzerland |

| 2000 | Bing J. Sheu | Nassda Corporation, Santa Clara, CA |

| 2001 | Hari C. Reddy | California State University, Long Beach, CA |

| 2002 | Josef A. Nossek | Munich University of Technology, Germany |

| 2003 | Giovanni De Micheli | Stanford University, Stanford, CA |

| 2004 | M.N.S. Swamy | Concordia University, Montreal, Canada |

| 2005 | Georges Gielen | Katholieke Univ., Leuven, Belgium |

| 2006 | Ellen Yoffa | IBM Corporation |

| 2007 | Ljiljana Trajkovic | Simon Fraser Univ., BC, Canada |

| 2008 | Maciej Ogorzalek | Jagiellonian Univ., Krakow, Poland |

| 2009 | David J. Allstot | Univ of California, Berkeley, USA |

| 2010 | Gianluca Setti | Università degli studi di Ferrara, Italy |

| 2011 | Mani Soma | University of Washington |

| 2012-2013 | Thanos Stouraitis | University of Patras, Greece |

| 2014-2015 | Vojin Oklobdzija | University of California, Davis |

| 2016-2017 | Franco Maloberti | University of Pavia, Italy |

| 2018-2019 | Yong Lian | |

| 2020-2021 | Amara Amara | France |

Notice that the Society did not have a President resident in an IEEE Region outside the USA until 1999 (George Moschytz).

Conferences of the Society

The first outside the USA

The IRE (then IEEE) Circuit Theory Group developed an international perspective at a very early stage.

Initially it supported several different conferences related to Circuit Theory, but then decided to concentrate support on one Symposium per year (the forerunner of ISCAS).

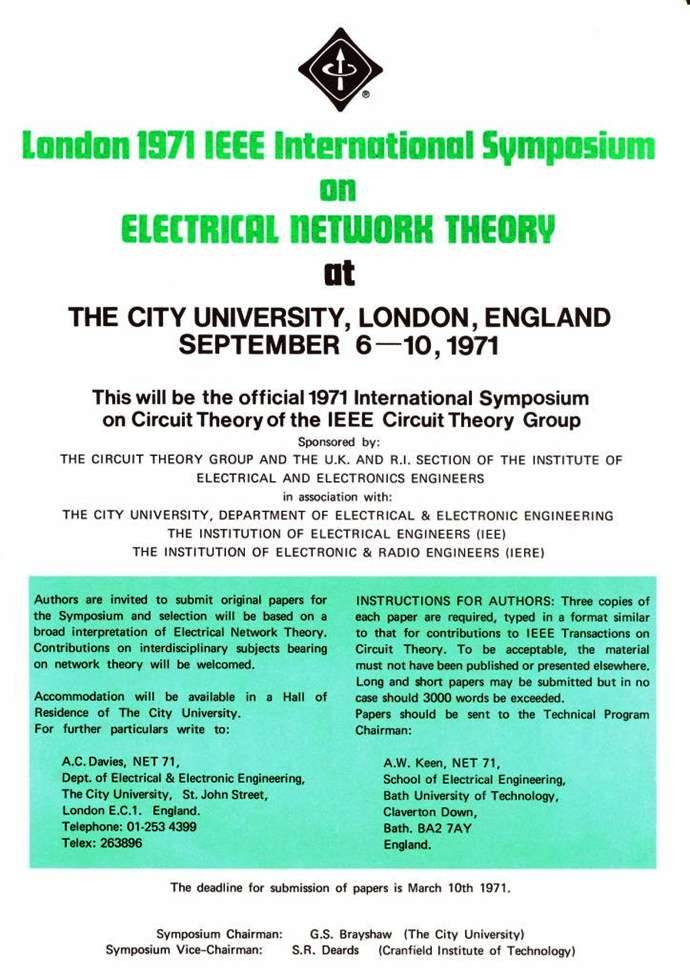

After holding this event a couple of times in USA, by 1969 there was a wish to hold it outside the USA. A bid in May 1969 from the Circuit Theory Chapter of the IEEE United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland Section to host it in London, England in 1971, was accepted in August 1969.

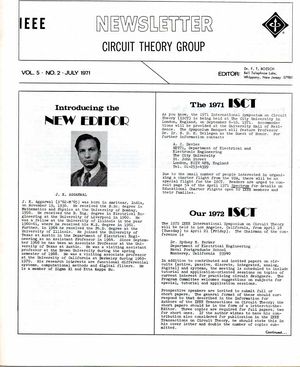

An announcement in the March 1971 Newsletter of the Circuit Theory Group and the Call for Papers are illustrated here.

Some concerns were expressed at the time about the effect of a ‘financial downturn’ on the attendance, and the registration fee was increased slightly to compensate. The editor of the same March 1971 Newsletter (Frank Boesch) wrote ‘….the economic condition of the engineering community in the United States is presently very poor……’

He also quoted some airline ticket costs: New York to London $210, and London to New York $255 – with a possibility of Charter Flights for $175 round trip. Numerically those are comparable to today’s costs, and considering the inflation since 1971, it is evident how dramatically the real cost of flying has fallen.

A postal strike in UK at the time of paper submission and review led to some temporary worries, but the event was judged to be a success and led directly to the policy of regularly holding ISCAS outside the USA which has been maintained ever since then. A notable advantage of holding the conference in England was that people who, for "political reasons" related to the Cold War, etc. could not attend an event in North America were able to attend, and in many cases, present papers. For example one delegate was from Cuba, and seven from Hungary. Just afterwards, there was a Summer School on Circuit Theory, held in Tale, Czechoslovakia, and a group of the delegates from North America were able to travel together to attend this too, something which would otherwise have been difficult for them. It also meant that they could meet people working in Circuit Theory from various countries in the 'East European' domain, who at that time had no possibility of getting permission to travel to Western Europe or North America.

Although the London Symposium was organised in the full knowledge of and with some cooperation from the National Society (IEE), some of the organisers feared that ‘retribution’ from IEE might follow afterwards. An indirect consequence was the initiation with the assistance of IEE of the ECCTD series of conferences, still held every two years in Region 8, which some staff and members of IEE hoped would keep IEEE out of Europe – in fact, there has normally been a cooperative association between IEEE CAS and ECCTD.

Anthony C. Davies

(Written in March 2003 for the CAS Society Directory - ninor amendments and additions 2021)

The Annual Symposium of the CAS Society

The first annual symposium was held in Miami Beach, Florida, in December 1968. Prior to that the Circuit Theory Group had co-sponsored (apparently without financial involvement) several meetings in the Circuit Theory field: the Midwest Symposium on Circuit Theory, the Allerton Conference on Circuit Theory, etc. A decision was taken to concentrate on supporting only one event per year soon after the Miami Beach event.

The international perspective which characterized the Circuit Theory Group can be judged from the decision to hold this event in London, England in 1971 - a decision in principle to do so must have been taken not later than 1969.

Although the Society has sponsored and co-sponsored many different series of conferences and continues to do so, the primary annual conferences is the the International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS).

The following list gives the date, location and general chairman of ISCAS since its inception:

| Date | Venue | General Chairman |

| 1968 | Miami Beach, Florida | Omar Wing |

| 1969 | San Francisco, CA | unavailable |

| 1970 | Atlanta, Georgia | H.E. Meadows |

| 1971 | London, England | George S. Brayshaw |

| 1972 | Los Angeles, CA | Sydney R. Parker |

| 1973 | Toronto, Canada | Kenneth C. Smith |

| 1974 | San Francisco, CA | Sanjit K. Mitra |

| 1975 | Boston, MA | John Logan |

| 1976 | Munich, Germany | Rudolf Saal |

| 1977 | Phoenix, Arizona | William Howard |

| 1978 | New York City | H.E. Meadows |

| 1979 | Tokyo, Japan | Yosiro Oono |

| 1980 | Houston, Texas | Rui J.P. de Figureido |

| 1981 | Chicago, Illinois | Benjamin J. Leon , M.E. Van Valkenburg |

| 1982 | Rome, Italy | Antonio Ruberti |

| 1983 | Newport Beach, CA | George Szentirmai |

| 1984 | Montreal, Canada | M.N.S. Swamy |

| 1985 | Kyoto, Japan | Toshio Fujusawa |

| 1986 | San Jose, CA | George Szentirmai |

| 1987 | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | Samuel Bedrosian |

| 1988 | Helsinki, Finland | Yrjo Neuvo |

| 1989 | Portland, Oregon | Tran Thong |

| 1990 | New Orleans, Louisiana | Anthony Michel, Michael Sain |

| 1991 | Singapore | J.C.H. Phang |

| 1992 | San Diego, CA | Stanley A. White |

| 1993 | Chicago, Illinois | Wai-Kai Chen |

| 1994 | London, England | Robert Spence |

| 1995 | Seattle, Washington | Robert J. Marks II |

| 1996 | Atlanta, Georgia | Philip E. Allen |

| 1997 | Hong Kong | Tony T.S. Ng, Ming Liou |

| 1998 | Monterey, California | Sherif N. Michael |

| 1999 | Orlando, Florida | Wasfy B. Mikhael |

| 2000 | Geneva, Switzerland | Martin J. Hasler |

| 2001 | Sydney, Australia | Graham R. Hellestrand, David J. Skellern |

| 2002 | Phoenix, Arizona | David J. Allstot, Sethuraman Panchanathan |

| 2003 | Bangkok, Thailand | Sitthichai Pookaiyaudom, Chris Toumazou |

| 2004 | Vancouver, BC, Canada | Andreas Antoniou |

| 2005 | Kobe, Japan | Nobuo Fuji |

| 2006 | Kos, Greece | Thanos Stouraitis |

| 2007 | New Orleans | Magdy Bayoumi |

| 2008 | Seattle, Washington | David Allstot |

| 2009 | Taipei, Taiwan | Jhing Fa Wang |

| 2010 | Paris, France | Amara Amara |

| 2011 | Rio De Janeiro, Brazil | Paulo Diniz |

| 2012 | Incheon, Korea | Myung Sunwoo |

| 2013 | Beijing, China | |

| 2014 | Melbourne, Australia | |

| 2015 | Lisbon, Portugal | |

| 2016 | Montreal, Canada | |

| 2017 | Baltimore, Maryland USA | |

| 2018 | Firenze, Italy | |

| 2019 | Sapporo, Japan | Hiroshi Tsutsui, Hokkaido Univ. |

| 2020 | VIRTUAL CONFERENCE |

Editors of CAS Society Publications

The reputation and achievements of the CAS Society are substantially dependent upon the Transactions, and while the content is created by the authors (with not insignificant contributions from reviewers), the Editors are responsible for the overall quality and timeliness of what is published. From the very first issue of the IRE Circuit Theory Group, the Transactions have been the source of many of the fundamentals which have led to the spectacular achievements of modern electronic engineering. Because the names of the Editors are often recorded only on the cover pages of the Transactions, and these pages are frequently discarded by libraries as part of the process of binding the annual volumes, the identities of the Editors are easily lost, especially for early issues. The list below is intended to help to preserve this heritage.For many years, the change in editor took place in mid-year. More recently, the changes have been on a Calendar year basis (normally a two year term starting in January). Notice that initially and for several years, all editors were from USA, though increasingly, content came from authors outside the USA. A more recent trend has been many more editors from outside USA.

Editors of the Transactions on Circuit Theory

The first issue was December 1952

| W.H. Huggins | John Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA | 1954-1957 |

| W.R. Bennett | Bell Telephone Labs, NJ, USA | 1958-1960 |

| M.E. Van Valkenberg | Univ. of Illinois, Urbana, USA | 1961-1963 |

| Norman Balabanian | Syracuse University, NY, USA | 1963-1965 |

| Dante Youla | Poly. Inst. of Brooklyn, NY, USA | 1965-1967 |

| Benjamin Leon | Purdue University, IN, USA | 1967-1969 |

| Gabor Temes | UCLA, CA, USA | 1969-1971 |

| George Szentirmai | Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA | 1971-1973 |

At the end of 1973, the title ‘Circuit Theory’ was dropped and replaced by ‘Circuits and Systems’, used from January 1974.

Editors of the Transactions on Circuits and Systems

| Leon Chua | Univ. of California, Berkeley, CA, USA | 1973-1975 |

| Omar Wing | Columbia University, New York, USA | 1975-1977 |

| Alan N. Willson | UCLA, CA, USA | 1977-1979 |

| Ming L. Liou | Bell Telephone Labs, NJ, USA | 1979-1981 |

| Anthony Michel | Iowa State Univ., Ames, IA, USA | 1981-1983 |

| Rolf Schaumann | Univ. of Minnesota, USA | 1983-1985 |

| Andreas Antoniou | Univ. of Victoria, Victoria, BC, Canada | 1985-1987 |

| Yen-Long Kuo | Bell Labs, North Andover, MA, USA | 1987-1989 |

| Ruey-Wen Liu | Notre Dame University, IN, USA | 1989-1991 |

In January 1992, the Transactions were split into two parts, TCAS-I and TCAS-II, subsequently each with its own editorial team. TCAS-I was allocated to 'Fundamental Theory and Applications' and TCAS-II to 'Analog and Digital Signal Processing'. After a while this distinction was not easy to sustain, and the two parts were later discontinued and replaced by a new format with part 1 being for 'regular papers' and part 2 being for 'express briefs (short papers).

Editors of the Transactions on Circuits and Systems, Part I

| Wai-Kai Chen | Univ of Illinois, Chicago, USA | 1991-1993 |

| Martin Hasler | EPFL, Lausanne, Switzerland | 1993-1995 |

| Josef Nossek | TU München, Germany | 1995-1997 |

| Pier Paulo Civalleri | Politecnico di Torino, Italy | 1997-1999 |

| M.N.S. Swamy | Concordia University, Montreal, Canada | 1999-2001 |

| Tamás Roska | SZTAKI, Budapest, Hungary | 2001-2003 |

| Keshab Parhi | Univ of Minnesota, MN, USA | 2004-2005 |

| Sankar Basu | National Science Foundation, Arlington, VA, USA | 2006-2007 |

| Gianluca Setti | Univ of Ferrara, Italy | 2008- |

Editors of the Transactions on Circuits and Systems, Part II

| Wai-Kai Chen | Univ of Illinois, Chicago, USA | 1991-1993 |

| Dave J. Allstot | Univ. of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA | 1993-1995 |

| John Choma | USC, Los Angeles, CA, USA | 1995-1997 |

| Edgar Sanchez-Sinencio | Texas A&M Univ, TX, USA | 1997-1999 |

| Chris Toumazou | Imperial College London, England | 1999-2001 |

| Ian Galton | UC, San Diego, CA, USA | 2001-2003 |

| Sankar Basu | National Science Foundation, Arlington, VA, USA | 2004-2005 |

| Gianluca Setti | Univ of Ferrara, Italy | 2006-2007 |

| U.-K. Moon | Oregon State Univ. Corvallis, OR 97331, USA | 2008- |

Editors of the Transactions on Computer Aided Design

The first issue was January 1982

| Ronald A. Rohrer | General Electric Co, USA | 1982-1984 |

| Robert W Dutton | Stanford University, CA, USA | 1985-1987 |

| Andrzej Stojwas | Carnegie Mellon Univ, PA, USA | 1988-1989 |

| Michael Lightner | Univ. of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA | 1990-1991 |

| Alfred Dunlop | AT&T Bell Labs, NJ, USA | 1991-1993 |

| Malgorzata Marek-Sadorska | UC Santa Barbara, CA, USA | 1993-1995 |

| Randal Bryant | Carnegie Mellon Univ, PA, USA | 1996-1997 |

| Giovanni De Micheli | Stanford University, CA, USA | 1997-2001 |

| Kartikega Mayaram | Oregon State Univ., Portland, OR, USA | 2002-2005 |

| E. Macii | Politecnico di Torino, Torino, Italy | 2006 |

Editors of the Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology

The first issue was March 1991

| Ming Liou | Bellcore, USA (then Univ. of Sci. and Tech, Kowloon, Hong Kong) | 1991-1995 |

| Ming T Sun | Univ. of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA | 1995-1997 |

| Ya-Qin Zhang | Microsoft, Cranbury, NJ, USA | 1997-1999 |

| Weiping Li | Webcast Technologies, Sunnyvale, CA, USA | 1999-2001 |

| T. Sikora | TU Berlin, Germany | 2002-2005 |

| C.W. Chen | Univ. of Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA | 2006- |

The Newsletters and Magazines

From the early days of the Circuit Theory Group, a simple Newsletter was sent to all the members.

At first issued irregularly, in 1959 it became a quarterly publication.

This developed to include some technical articles, and was renamed the Magazine, although subsequently it was again called a Newsletter.

Later, some other IEEE Societies began the production of popular high quality magazines, such as the IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, and for a while, the Circuits and Systems Society was one of the particpating sponsors of the Circuits and Devices Magazine. The idea then developed to produce a Magazine for the Circuits and Systems Society and a transition-path was planned to convert the Newsletter to a Magazine. The Editor during this transitional phase was Michael Sain. As the publication developed and improved, it was necessary to get formal IEEE approval for it to be produced within the 'IEEE family of publications' and after some opposition from several sources, this approval was obtained, and now the Society has a colourful magazine incorporating good quality tutorial and survey papers covering many topics within the overall field of interest of the Society.

Since 2007, there has also been a bi-monthly Newsletter, containing only brief news items for members of the Society (e.g. no technical articles).

The Society has always had a strong international perspective and membership, and for a short while, around 2000, tried a membership encouragement drive using other languages than English, following a trend adopted by some other IEEE Societies, for example Electron Devices (example leaflets shown below the images of Magazine Front Covers).

Newsletter issues

The Circuits and Systems Society: some historical remarks about the Original Core Subject Area

(mostly from the CAS Society Directory, 2002-2003, written by Anthony C Davies)

A Tale of Long Ago

Many of the early members and contributors were passive-filter designers. The design of high-performance passive filters was a very specialized topic, understood by only a few experts, but it was crucial to the implementation of line-based telecommunications systems and quite important in radio communications.

For many years, industry generally used the ‘Image Parameter’ method, which provided an ‘easy’ design route (for which slide-rule accuracy was often enough) but which involved inherent approximations in terms of realization of the frequency characteristics of the ‘design’. The Insertion Loss method, pioneered by Cauer and by Darlington, was able to produce designs for which, with ideal lossless components, an exact synthesis of a prescribed transfer function could be obtained. However, the theory was not easy to understand at the time, accurate and extensive calculations were needed, and with only primitive mechanical calculating machines available, the method was laborious and did not find many supporters, and industry generally neither understood nor made use of the method.

Filter designers were thus often regarded as ‘a race apart’ - engaged in using abstract theories in an almost ‘black art’ of which most engineers had no understanding. Even when digital computers became available to assist in the design calculations, it was at first necessary to use triple-length arithmetic (or more) in order to obtain sufficient precision for useful designs.

Active filters were occasionally suggested, but never used in practice except for very low frequency (sub-audio) applications, such as mechanical servomechanisms - the only available active element was the thermionic valve (tube) which was expensive, unreliable, and required high voltage power supplies.

The beginnings of the Circuit Theory Group were also involved in educational aspects of Circuit Theory - with a strong mission to teach fundamentals of the subject, as opposed to the ad hoc approaches which characterized the circuit-teaching in much of the university electrical engineering curriculum. The subject offered some key advantages: the possibility of an axiomatic approach, rigorous development of a theory uncontaminated by the imperfections of practical components and experiments, and the prospect of formal synthesis - being given a ‘requirement’ and producing, by a step-by-step procedure guaranteed to succeed, a circuit implementation. Although the implementations were ‘theoretical’ ones, requiring idealized linear, time-invariant and often lossless components, there was a real sense in which this represented an alternative to much of engineering practice in other subjects. It also laid a pedagogical foundation, widely believed (at least by the Circuit Theory people) to be a strong contender to be the basis for an engineering education in all disciplines.

The concept of the ‘two port’ (or ‘four-pole, as it was more often called at the time) originally put on a systematic foundation by Feldtkeller in Germany in the mid-1930’s [see R. Feldtkeller ‘Einführung in die Vierpoltheorie der electrischen Nachrichtentechnik’ Verlag von S. Hirzel, Leipzig, 1937], became very important in Circuit Theory. It also laid the foundation for the treatment of transistors as circuit elements.

There was much hope from ‘analogies’ too. The realization that the successful field of electrical circuit theory could apparently be applied just as well to mechanical, thermal, acoustical and other dynamical systems seemed to suggest that electrical circuit theory could become the foundation for many branches of engineering and not only electrical engineering - unfortunately, the lack of good practical implementations of the ‘ideal linear lumped time-invariant’ circuit elements in non-electrical systems severely restricted the extent to which this hope could be realized.

The linear, lumped, passive, finite, bilateral, time-invariant assumptions limited the scope of much Circuit Theory in these early years but nevertheless provided a broad field in which significant fundamental research could be done, and provided the ‘training ground’ for many graduate students and professors.

There were some failures to adequately deal with electronic components - the practice of actual electronic circuit design (at that time involving thermionic valves/tubes) did not conform well to the formalized design processes advocated by many of the leaders in circuit theory, in many cases, it involved non-linearity in an essential way (so that a linear time-invariant assumption was simply not useful) and there was a lack of clear and agreed ideas about how to extend the set of ideal linear passive elements to take into account ‘activity’ in a suitably idealized way to make a formal extension of passive circuit theory. Active circuits were often simply defined as those circuits, which were ‘not-passive’, and little more was said about them.

What are the Real Fundamentals?

The driving point impedance of any linear time-invariant passive system / circuit / network is a positive-real function of complex frequency. Further, if a circuit is constructed from a finite number of linear lumped passive time-invariant components, e.g. from the familiar ideal {R, L, C, M, ideal transformer, gyrator} set, then this driving point impedance is a positive real rational function, for which a formal synthesis procedure is available. Brune [O. Brune ‘Synthesis of a finite two-terminal network whose driving point impedance is a prescribed function of frequency’, J. Math. Phys. 10, 191, 1931] showed that every such rational function could be systematically implemented by a systematic construction (though requiring, in most cases, inconvenient mutually coupled inductive elements or ideal transformers). Finally, Bott and Duffin [R. Bott and R.J. Duffin ‘Impedance synthesis without the use of transformers’, J. Appl, Phys. 20, 816, 1949] were able to use the Richards transformation [P.I. Richards ‘A special class of functions with positive real part in a half-plane’, Duke Math. J., 14, 777, 1947] to provide a transformerless (e.g. R,L,C) synthesis procedure.

These results appeared to be of great significance at the time - especially given the analogies with non-electrical systems - and the lack of practical utility of many of the synthesized circuits was more-or-less overlooked. However, it represented the achievement of an ideal missing in much of engineering then and today.

Starting with a precise, formal (mathematical) statement of the problem to be solved and achieving a realization by a systematic process guaranteed in advance by theory to succeed (in a finite number of steps) represented a major achievement, the importance of which can hardly be overstated, and it was also a philosophy which seemed ideal for the educational foundation of electrical engineers. (Would it not be nice if today’s office-PC software could be designed by such procedures).

Darlington made an outstanding contribution, which must have appeared to many at the time to be of no practical significance whatsoever. He was able to extend the synthesis methods for driving-point impedances to show that any positive real rational function could be implemented as a structure of lossless (e.g. L, C) elements and exactly one positive resistor.

Despite the apparent practical uselessness of this theoretical result, relationships between the magnitude of scattering parameters of lossless two-ports enabled this to be related to the implementation of a prescribed magnitude-frequency response as the insertion loss of a lossless two port with resistive terminations. This led directly to a solution to the problem of designing the high-performance frequency selective filters upon which the whole of the analog frequency-division multiplex based line and radio communications industry depended at least until digital technology increasingly replaced them.

Note the absence of any consideration of non-reciprocity in the foregoing - Tellegen invented the Gyrator - a ‘missing’ element was needed to complete the theory for the ‘passive’ domain, in order to have non-reciprocity without activity. The ideal gyrator provided just such a passive device [B.D.H. Tellegen,’ The gyrator; a new network element’, Philips Research Report, 3, 81, 1948].

Subsequently, it became fashionable to try to devise ‘new circuit elements’, many of which did not survive or achieve importance. Among the more abstract and at first apparently useless concepts are a two-terminal element for which both the voltage and current are always zero and a two-terminal element for which both the voltage and the current are undefined. The description of such elements might cause the practically-minded engineer to check if the cover date of the publication he/she was reading was 1st April, yet these two elements, combined together as a ‘nullor’, represent a practically useful model of an ideal transistor and of an operational amplifier, and have found a permanent place in Circuit Theory.

Graph Theory. The concept of an electrical circuit as a linear graph formed the foundation for much of the theory and a basis for systematic methods of analyzing complicated networks, and as a result, Graph Theory laid the basis for the computer based analysis methods and simulators (such as SPICE) which we now take for granted, and which provide one of the foundations upon which the success of modern integrated circuit technology stands. Kirchhoff’s first and second laws were ‘graph theory based’ but what Weinberg called Kirchhoff’s third and fourth laws were almost unknown, yet provide a foundation for much of the network theory developed (using concepts of trees and cutsets, etc.) which is essential for the systematic analysis of large networks. For example, the determinant of the nodal admittance matrix is the sum of all the tree-admittance products - so enabling all numerical processing to be side-stepped and demonstrating immediately and dramatically the link between circuit topology and circuit transfer-functions. A book by S. Seshu and M.B. Reed (Linear Graphs and Electrical Networks) had a very strong influence on its readership (Addison Wesley, 1961)

Activity: Controlled sources were a natural way of introducing activity into otherwise passive circuits. However, since they were also used in the representation of passive circuits (for example in modeling mutual inductance, ideal transformers and gyrators) they did not offer the convenience of being a distinctive element to be added to the passive set to introduce the concept of activity. Initially, it seemed that the unlikely candidate of the negative impedance convertor (NIC) was going to fill this role.

The motivation for developing active filters was mainly the elimination of inductors (on grounds of their size, weight, and non-ideal properties).

Linvill [J.C. Linvill,’RC Active Filters’, Proc. IRE, 42, 55, 1954 ‘Synthesis of Active Filters’, Poly. Inst. Brooklyn, MRI Symposia series, 5, 453, 1955] showed that by using just a single voltage-inversion negative impedance convertor (NIC) as the active element, any rational function could be realized as the transfer function of an RC-active circuit, and shortly afterwards, Yanagisawa [T. Yanigasawa,’RC active networks using current inversion negative impedance convertors’, Trans IRE, CT-4, 140, 1957] provided a simplified synthesis procedure, using a current-inversion NIC. This stimulated intensive research into Active-RC synthesis using the NIC, and many ideas for implementing such an idealized component using transistors. However, the enthusiasm was soon dampened by the realization that the sensitivity of the circuits was so high that they were almost useless in practice. In the following decade of work with the NIC the principal value seems, in retrospect, to have been in the production of doctoral theses and the launching of academic careers. Very few systems went into actual production as a result of this work!

What was apparently not realized by many from a passive filter background was well-known to most practicing electronics engineers: to get a low sensitivity with only one amplifier, a very high loop gain is needed - and the many inventive schemes to make a highly accurate NIC with two or three low gain transistors were doomed to failure. It was not until the invention of the integrated circuit OP-Amp by Bob Widlar at Fairchild that a cheap high-gain component became available to implement active-RC filters. It was then mainly the much older Sallen and Key structures [R.P Sallen and E.L. Key, ‘A practical method of designing active RC filters’, Trans. IRE, CT-2, 74, 1955], that survived the transition to engineering practice.

An important breakthrough came with the observation by Orchard [H.J. Orchard, ‘Inductorless Filters’, Electronics Letters, 2, 224, 1966] that the sensitivity to component tolerances in the classical doubly-terminated passive, lossless, LC ladder filters is exceptionally good, especially in the passband, because of the non-negative property of the insertion loss of such a passive structure, and this led to the understanding that imitating this behavior in active and digital filters was a route to getting the low sensitivity needed in practical circuits.

The large silicon area required for accurate resistors prevented successful single chip implementations of Active RC filters, and Switched-capacitor filters were the first practically successful approach to widespread implementation of high-performance filters in silicon monolithic form. Despite the need to distribute high-frequency clocks around the chip, they found their way into many real systems.

Digital filters were an inevitable development, although for a long time, their practical implementation was severely limited for real-time signal processing over the frequency ranges needed by communications systems. Although there were many attempts to implement digital filters in integrated circuit form, the development of the TMS 320 series of DSP chips by Texas Instruments was a major stimulus to converting these ideas to widespread use.

The usefulness of wave digital filters may sometimes be questioned, but the theory developed by Fettweis [A. Fettweis, ‘Wave Digital Filters’, Proc. IEEE, 74, 270, 1986] showed the unanticipated result that concepts from classical network theory (including passivity) could be transferred into the field of purely numerical processing of data, and that classical network theory did, after all, have something important to contribute to the emerging field of digital signal processing. In June 2001, the company Infineon Technologies AG celebrated the delivery of 50 million units of a subscriber-line filter product, each one of which contained several wave-digital filters

Non-linearity has not been mentioned so far - it was often considered unwelcome, to be avoided, either by pretending it was not there or by modifying designs so as to minimize its effects. A perfect world was often assumed to ‘linear, lumped, finite, time-invariant, passive, bilateral’, and anything falling outside this was regarded as unwelcome and harmful. It took the recent developments in dynamics and the discovery of chaos and fractals to demonstrate more widely that reality is non-linearity and that the real world is non-linear in a way that engineers need to understand and to exploit.

The rest of the story is not history, it is going on around us! A message embedded within the story is that what looks like useless theory today can often turn out to be an essential foundation for tomorrow’s technology.

Acknowledgements:

to Ben Leon, for the useful material that I extracted from his ‘History of the Circuits and Systems Society’ published in the Centennial Issue (December 1983) of the IEEE Circuits and Systems Magazine (vol. 5, No. 4), to Sean Scanlan for his observations about the technological significance of Darlington’s results on the synthesis of RLC networks, to George Moschytz who persuaded me, rather against my wishes, to create the first CAS Society Directory, to the CAS Executive Committee which gave me a free hand to define the concept, structure and content of the Directory and to Tom Wehner for filling in a lot of data and putting it all together in the CAS Society printed Directory (without which it would have remained in a partially completed state on the hard disc of my computer). Thanks are also due to many people who made appreciative comments about the CAS Society Directory and encouraged the production of updated versions (which continued annually from the first, dated 1999-2000, until at least the 2009 issue, produced by Magdy Bayoumi).

Tony Davies

More Historical Moments

An extract from the Minutes of a 22 March 1956 meeting of the AdCom of the IRE Circuit Theory Group:

“…. only by taking in more fringe areas (e.g. Transistor Circuits) can we really obtain more members..” “…consensus … not to have a membership drive…”

This extract appears to indicate that the AdCom members did not consider that the theory or design of circuits containing transistors was either important or within the real scope of Circuit Theory.

In view of subsequent developments in electronics, the description of Transistor Circuits as a ‘fringe area’ of Circuit Theory seems rather quaint, and certainly an indication of not foreseeing the future.

As described above, the initial field of interest was centred on linear passive time-invariant circuits, the later change in Society name from Circuit Theory to Circuits and Systems was said by some to enable anything that they wanted to be included in the Field of Interest, which has subsequently expanded to cover a range of topics which could surely not have been forseen by the early leadership of the Society.

The increasingly important subject of digital filters was initially not recognised by many in the leadership of the Society, and as a result, researchers in this area found a 'home' in what was then the IEEE Audio and Electroacoustics Group, which subsequently developed into the IEEE Signal Processing Society.

Time-varying systems were a minor topic until the development of switched-capacitor filters.

Non-linearity was at first considered a minor and mostly unwanted feature, considering only such aspects as harmonic distortion and intermodulation effects. Even though a proper explanation of oscillator behaviour required non-linear dynamics, this was generally avoided. Not untul the late 1980s did non-linear dynamics begin to take a significant place in the interests of the Society, concurrently with discoveries about and applications of chaos in engineering, and the development of over-sampled systems based on sigma-delta modulators and other inherently non-linear systems,.

Notable also is the often long gestation time for fundamental ideas to move into useful applications - an example is the Memristor, initially proposed by Leon Chua in 1971 as a 'missing' non-linear circuit component linking charge and magnetic flux, which did not find practical implementations and applications for nearly 40 years.

Further Reading

IEEE Circuits and Systems Society Website

IEEE UKRI Circuits and Systems Chapter History

A Short History of Circuits and Systems: From Green, Mobile, Pervasive Networking to Big Data Computing (River Publishers Series in Circuits and Systems), Franco Maloberti (Editor), Anthony C. Davies (Editor)