Technological Innovations in Sports Broadcasting

Also See: Televised sports

Baseball

Radio

The first radio broadcast of a baseball game occurred in Pittsburgh on August 5, 1921. The announcer, using a converted telephone for a mike, was Harold Arlin, a Westinghouse foreman and nighttime radio announcer who had previously announced the first football game over the radio. The station was KDKA, the nation’s first commercial radio station, which had previously made its mark by announcing the returns of the 1920 presidential election.

Later in 1921, the World Series was broadcast by RCA, whose head, David Sarnoff, later explained, “We had to have baseball in order to sell enough sets to on to other programming.” The spread of radio likewise benefited baseball: after one season on WMAQ, the Chicago Cubs had the highest receipts of any team in its league — although, as with later technological innovations, team owners worried that broadcasts kept people from the ballparks.

Television

The first baseball telecast was a college match between Columbia University and Princeton, broadcast in 1939 from Columbia’s Baker Field. At the time, there were around 400 receivers in the New York area — including one installed in the basement of Columbia’s Philosophy Hall by Edwin Armstrong (see Victor Wouk’s oral history) — but most of the audience was most likely at the RCA television facility in Rockefeller Center. The camera, positioned far from the action, panned from pitcher to batter in an attempt to follow the ball. The first major league broadcast on May 17, 1939, also used only one iconoscope camera. For an August game between the Reds and the Dodgers, a second camera was added, along with a telephoto lens for close-ups.

Cameras

With a large field and unpredictable action – unlike in hockey or football, the movement was not primarily from one end of a field to the other – baseball demanded a growing number of cameras (as well as baseball savvy on the part of their operators). By the first World Series telecast in 1947, stations used orthicon and image-orthicon cameras, better in low light, as well as a rack of wide angle, normal and telephoto lenses.

A center field camera, which would eventually displace the camera above home plate as the most important, was first introduced by Chicago’s WGN in a 1951 Little League game; it was later popularized by the 1955 All-Star Game. Team owners initially worried, as they would with increasingly long zoom lenses (80 mm by 1959), that the camera would steal the catchers’ signals.

The number and variety of cameras gradually increased. By the 1970s, it was common to cover a game with four to five cameras, but prominent national telecasts used more: for the 1983 All-Star Game, NBC used 13; in 2006, Fox used 28. ABC introduced the “Super Slo Mo” camera in 1984 during playoff coverage. In that same year’s World Series, NBC (which shared the baseball contract) upped the ante with its “Super Duper Slo Mo” camera, whose 90 frames per second tripled the usual 30.

Color

The first color telecasts were of Dodgers games in August and September of 1951, part of the campaign by CBS to establish its electronic-mechanical system as the standard (RCA’s all-electronic system would win out in 1952). The first use of color in a national game was by NBC for the 1955 “Subway Series” between the Dodgers and the Yankees. In 1967, WHDH covered the Red Sox using RCA TK-43 “Big Tube” cameras, which performed better in varying light conditions, including nighttime games. Baseball uniforms and even stadium seats soon became more colorful to make a better impression on TV.

Graphics

Initially, white lettering on flip cards was “supered” over the game image. Both images were at half-intensity, giving a washed-out look. By 1965, graphics were matted over the game image. The electronic character generator, with stored memory, was in use by the 1970s; the 1975 World Series featured yellow graphics that were updated during the game. With the rise of “sabermetric” analysis in the 1980s, which coincided with home computer use by fans, graphics increased to around 200 per game by 1998, with only 30-40 percent stored beforehand.

In the 1990s, with technology provided by its spin-off company Sportvision, Fox pioneered the use of pictorial graphics to track elements of the game. HitZone showed a hitter’s relative strength in different parts of the strike zone. Spray Charts indicated where a batter tended to hit the ball. FoxTrax showed the location of pitches relative to the strike zone. Fox also introduced FoxBox, a rectangle in the corner of the screen that provided live updates of game information.

Sound

Sound was relatively neglected until the 1980s, when stereo was introduced by networks and local stations. Wireless microphones were placed down the left and right field lines to improve the stereo effect, as well as in other places around the field to pick up specific sounds: the crack of the bat, umpire’s calls, the runner’s foot hitting a base. Microphones were turned on and off depending on the action, requiring sound engineers to be as baseball savvy as the camera operators.

Fox was again a pioneer, branding its sound system FoxVox. Among its dozens of microphones, FoxVox included parabolic reflector mircrophones to pick up the sound of the ball hitting the bat or the catcher’s gloves, pressure zone microphones to capture the sound of a player crashing against an outfield fence, and microphones embedded in first, second and third bases (see the patent).

Instant replay

Pioneered in football, instant replays first gained prominence in baseball during ABC’s 1965 game of the week telecasts. In the 1968 and 1969 World Series, NBC used them sparingly, usually just prior to commercial breaks. By 1991, however, CBS used 133 replays during one game, and by 1998 broadcast directors could ask for “sequences,” collections of related plays digitally stored by category.

Digital Television

The first hi-def transmission of a baseball game was on September 16, 1997. Harris Corporation broadcast the Orioles vs. Indians game to an audience of executives and journalists at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. As with CBS’s rollout of its color system in 1951, the intent was political, as the demonstration coincided with congressional hearings urging broadcasters to offer more HD programming. Harris CEO Philip Farmer described HDTV as “tailor made for baseball,” enabling fans to see a third more of the field at twice the clarity. Phased-in adoption of digital standards began at major stations in 1998.

Football

Radio

The first radio broadcast of a football game occurred in 1912. Professor F.W. Springer of the began an experimental radio station with the call numbers 9X1-WLB, from which he broadcast University of Minnesota home games to a small audience. Due largely to wartime restrictions, there would not be another radio broadcast of a football game until a 1920 contest between Texas A&M and Texas. KDKA, with announcer Harold Arlin, aired the 1921 match-up between the University of Pittsburgh and West Virginia University, known as the "Backyard Brawl." This was a commercially sponsored game.

The 1922 match-up between the University of Chicago and Princeton, touted as the "greatest game of the century," was the first to be broadcast long-distance. The sound of cheering throngs in Chicago's Stagg Field was transmitted via phone wires to New York City's WEAF (owned by AT&T) and then on to east-coast fans. WEAF also set up a truck in Manhattan's Park Row that used a radio receiving set to operate a public-address system, much to the delight of street crowds. This and other broadcasts of interregional games helped to make football a national sport.

Television

Telecasting began during the same year for both football and baseball. NBC, with Bill Stern at the microphone, experimented with the medium during practices at Fordham University and Long Island University in early 1939. The first telecast, a game between Fordham and Waynesburg College played in Triboro Stadium on Randall’s Island, occured on September 20, 1939. The audience of 9,000 fans at the game was likely four or five times the TV audience. The one Iconoscope camera, set up at the 40-yard line, transmitted static shots of moving players, who appeared miniscule when they were across the field and gigantic when they neared the camera.

Less than a month later, the first professional game (Brooklyn Dodgers vs. Philadelphia Eagles) was broadcast from Ebbets Field to fewer than 1,000 sets in the New York area. Two Iconoscope cameras, one in the mezzanine and one on the 50-yard line, transmitted a picture that, due to cloudy conditions, got darker and darker as the game progressed until NBC reverted to a radio broadcast. As an experiment, the Brooklyn coach used a monitor to get a better view of the game.

In1940, the Philco Radio and Television Corporation broadcast all University of Pennsylvanian home games using two Orthicon cameras, one on each 25-yard line. One, with a telephoto lens, did close-up shots. Except during World War II, Penn would continue broadcasting its games during the next decade. In 1949, Notre Dame, with a tremendous following in Chicago (and among Catholics nationwide), signed an exclusive broadcasting deal with Du Mont, with Chevrolet as a commercial sponsor. Though many schools feared falling attendance in the wake of broadcasts, this established the longstanding partnership of football and TV.

Instant Replay

The instant replay was invented during a football game — the December 7, 1963 Army-Navy Game — after Army quarterback Rollie Stichweb ran the ball in from the two-yard line. CBS director Tony Vera called for the videotaped recording of the touchdown. The replay ran without a hitch, prompting Vera to shout, "Oh my God, it works!" The rhythms of football turned out to be ideal for the instant replay: moments of intense action difficult to fully comprehend in real time alternate with long lulls that provide perfect times for reviewing past plays. Ampex Corporation, which introduced the first video recorders to the National Association of Broadcasters in 1956, worked with ABC to develop a system that would allow 30 second replays within 4 seconds. They system included three speeds of slow motion and the ability to freeze frames. The technology would soon spread to other sports.

Graphics

ESPN introduced the 1st and Ten system during the 1998 Super Bowl. This was the year Stan Honey left Fox to become a founder of Sportvision. The system paints a virtual yellow line on a football field to indicate the first-down line. Because the target in this case is stationery, its position can be calculated using only the television cameras. The unique topography of each football field and the curvature created by sharp-focus lenses make it a challenge, however, to paint a virtual line that appears flush to the field and parallel to the actual yard lines.

The graphic is subtle and naturalistic: like a real yard line, parts of it can be obscured when "covered" by mud. At the same time, it increases the ability of even practiced viewers to follow the progress of the game. It has thus avoided the controversy that surrounded the more showy FoxTrax hockey puck. Since 1998, it has gradually extended to nearly all professional and college games.

Hockey

Graphics

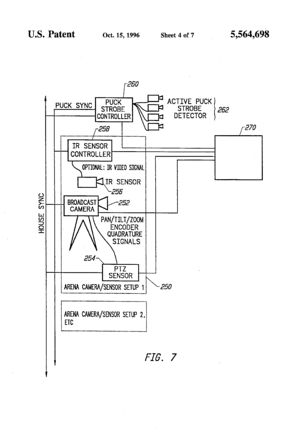

Fox Television introduced the FoxTrax puck tracking system in 1996 at the All-Star game. Fox, which was owned by NewsCorp, had just won the rights to broadcast National Hockey League games and was determined to expand the audience for televised ice hockey in the United States, which at the time was relatively small compared to the other professional sports. Fox looked to bold innovation as way to draw new viewers to hockey. Fox’s idea was to track the very small hockey puck, which often moved at speeds even too fast for the video cameras to record, and then color-enhance the puck so that views could always follow it real-time. As the puck travelled through the air, its motion was shown as a blue streak. When the puck went faster than 70 mph, the streak became red. To accomplish this feat, the engineering team pushed the technology of the day to its limits.

The FoxTrax puck tracking innovation was a technological tour-de-force that stirred up considerable controversy. The graphic was popular with some viewers, but was also widely ridiculed by hockey purists. Canadians, in particular, saw it as evidence of American unfamiliarity with the game. Fox loved the publicity. The All-Star game in 1996 produced the highest ratings ever for an All-Star game. The technology was used for 3 hockey seasons, and was only dropped when ESPN won the broadcast rights to NHL hockey.

As innovative as the FoxTrax puck track system was, the question remains, would a glowing puck have increased ice hockey viewership around the world, particularly during the Stanley Cup Championships?

The Olympics

Also See: Technological Innovations and the Summer Olympic Games

Television and Film

The 1936 Summer Olympics, hosted by Nazi Germany — though slated for Berlin by the IOC in 1931, before Hitler came to power — marked the first live television coverage of a sports event. Two German firms, Telefunken and Fernseh, respectively used RCA and Farnsworth equipment to broadcast events at 180 lines and 25 frames per second. The broadcasts, totaling 72 hours, were received by special viewing booths, called "Public Television Offices," in Berlin and Potsdam. Three cameras were positioned, at various times, at the end of the 100 meter track, at the Swimming Stadium, and at the Marathon Gate, as well as a number of other locations. Two cables connected the Reich Sport Field with a television transmitter at the Berlin radio tower.

The 1936 Olympics were also the subject of Leni Reifenstahl's famous sports documentary, Olympia, which was released in 1938. Though spearheaded by Hitler as a way to glorify his Germany for an international audience, the film at times went against the grain of Nazi propaganda. For example, it gave extensive and dramatic coverage to Jesse Owens' triumphs. Reifenstahl's cameramen Hans Ertl pioneered techniques that, in some cases, were not used in television coverage until the 1990s. He built a camera, used for the Diving events, that was encased in a box to enable shooting both above and below the water line. A similar camera, billed as an Olympic first, was used in 1992 in Barcelona. Ertl also developed a camera to film the 100 meters that was catapulted (without an operator) along a steel track. Its speed was calibrated to be a little faster than the sprinters, filming them with the camera facing backwards. Though successful in trials, the system was ultimately barred from the Olympics for fear that it would distract the runners.

London hosted the first summer Games in 1948 after World War II. These Games were the first to be shown on home television. The British Broadcasting Company (BBC) purchased the rights to transmit the Games at a cost of US $3,000 to an official audience of 500,000 people within the British Isles. The first American telecast of the Olympics was from Squaw Valley, California, in 1960. CBS provided a scant 15 hours of coverage. ABC began broadcasting the games in 1964 using a more personality-oriented approach. It provided over 60 hours of coverage by 1972.

Timing Systems

Seiko, the official timer for the 1964 Tokyo Games, unveiled a new, fully electronic automated timing system that boosted accuracy tremendously. The system linked a starting pistol with a quartz timer and a photo-finish apparatus to record finish times, making it possible to record results down to 1/100th of a second. Seiko credits the company’s technology development for the Games during the early 1960s as the impetus for its other timing technology innovations, including the world’s first commercial quartz wristwatch.

Graphics

Olympic broadcasting reached new heights at the Sydney Games in 2000. Orad Hi-Tec Systems Ltd., a world leader in virtual set technologies, advertising and sports broadcasting tools, introduced the first use of virtual imaging in Olympic competition. Its Virtual World Record Line debuted during Australian Nine Network’s television and Web coverage of the Olympic qualifying swimming trials. The line, connected directly to the electronic timing in the event pool, featured a superimposed line on the water’s surface and graphics depicting existing world records.

Motor Sports

Graphics

RACEf/x, introduced by Sportvision and NASCAR in 2001, further advanced Sportvision’s formula of providing a wealth of information, useful to experienced fans and novice viewers alike, in a clean graphic format. The difficulty of discerning the leader on a circular track offered the opportunity to win over fans simply by highlighting the car in front. In addition, a “virtual dashboard” — overlaid onto a shot taken from inside a car’s front windshield — indicates such things as throttle, braking, fuel flow and RPM. Multiple technical problems had to be overcome, however. Because racetrack conditions (including fencing that covers half the sky) interferes with GPS sensors, the units bolted into each car are designed to locate the car using two satellites, and sometimes only one, rather than the usual four. The optical illusion of boxes floating over specific cars faced challenges similar to that of 1st and Ten — with an even longer zoom length — in addition to the tendency of the cameras to bounce as they tilt and pan.

Boxing

Radio

The first sports broadcast took place on April 11, 1921. Pittsburgh Post sportswriter Florent Gibson reported live from the Motor Square Garden ringside in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, for Westinghouse's station KDKA on the boxing match between lightweight Johnny Ray, also known as Harold Pitler, and Johnny Dundee, also known as Giuseppe Carrora. The fighters ended with no decision after ten rounds.

The second sports broadcast, on July 2, 1921, was also a boxing match. Promoter George "Tex" Rickard arranged a heavyweight contest between American champion Jack Dempsey and French champion Georges Carpentier at Boyle's Thirty Acres in Jersey City, New Jersey. Timed close to Independence Day, the match between the long-time allies' best fighters promised to attract attention. Julius Hopp, manager at Madison Square Garden, proposed the broadcast to Rickard as a fundraiser for the American Committee for Devastated France. After Rickard signed off on the plan to have donations made at venues equipped with loudspeakers and radio receivers, Hopp contacted J. Andrew White of the National Amateur Wireless Association for help in recruiting volunteers to set up the transmission and reception systems. White solicited his boss, David Sarnoff, general manager of the newly formed RCA, to underwrite the broadcast for $1,500 and contribute technical staff. Sarnoff agreed in order to help demonstrate the market potential of radio, which he had been championing for the previous five or six years.

With an endorsement by Franklin D. Roosevelt, the U.S. Navy and General Electric Company loaned a 3.5 kilowatt transmitter. RCA engineer J. Owen Smith installed it in a shack at the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railway's Hoboken terminal and obtained a temporary transmitter license for radio station WJY. White described the fight from ringside into a telephone, which was connected to a microphone at the transmitter by Smith.

Dempsey knocked out Carpentier in the fourth round, coincidentally just as the GE transmitter overheated and burned out. With as many as 300,000 people listening, according to RCA's summary of reports from listeners, the broadcast helped fuel the sale of consumer radio receivers that fall and winter.

References and Links

Covil, Eric C. "Radio and its Impact on the Sports World" American Sportscaster Online, visited 16 May 2012.

Downing, Taylor. 1992. Olympia (BFI Film Classics). London: British Film Institute.

Schultz, Brad. 2002. Sports Broadcasting. Boston: Focal Press.

Smith, Curt. 1987. Voices of the Game: The First Full-Scale Overview of Baseball Broadcasting, 1921 to the Present. Diamond Communications.

Smith, Ronald A. 2001. Play-by-Play: Radio, Television and Big Time College Sport. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Television History: The First 75 Years, “1936 German (Berlin) Olympics”

Walker, James R. and Bellamy, Robert V. 2008. Center Field Shot: A History of Baseball on Television. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.