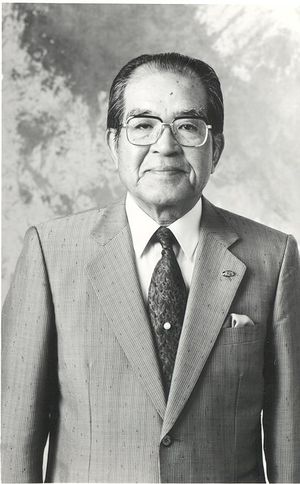

Oral-History:Katsutaro Kataoka

About Katsutaro Kataoka

In this oral history Katsutaro Kataoka, the founder and innovator behind Alps Electric Company, discusses the rise of his company in the Japanese electronic components markets. Kataoka graduated from Kobe University in the 1930’s and joined the Toshiba Corporation. After a short time with Toshiba, Kataoka entered the Japanese military. In 1943 he returned to Toshiba, but left again in 1945 to start his own company, Alps Electric.

The interview focuses largely on Kataoka’s business strategies and his success as a secondary components manufacturer. He talks about the various products that Alps has produced over the years, from radio technologies, to TV tuners, to computer printers and floppy disk drives. Kataoka discusses Japan’s success in the consumer electronics industry and analyzes the pre and post-war industry relationships between the United States and Japan. He talks about the role of Japanese “Keiretsu” or business groups, particularly the Electronics Industry Association of Japan, and reasons why the U.S and Japan have followed different trajectories in the consumer electronics industry. Kataoka concludes the interview with a discussion of Alps product strategy and nostalgia for the pre-Korean war industry relationships between the United States and Japan.

About the Interview

KATSUTARO KATAOKA: An Interview Conducted by William Aspray, Center for the History of Electrical Engineering, February 17, 1993

Interview #147: Engineers as Executives Oral History Project, sponsored by Center for the History of Electrical Engineering, The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc.

Copyright Statement

This manuscript is being made available for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the IEEE History Center. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of IEEE History Center.

Request for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the IEEE History Center Oral History Program, IEEE History Center, 445 Hoes Lane, Piscataway, NJ 08854 USA or ieee-history@ieee.org. It should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user.

It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows:

Katsutaro Kataoka, an oral history conducted in 1993 by William Aspray, IEEE History Center, Piscataway, NJ, USA.

Interview

Interview: Katsutaro Kataoka Interviewer: William Aspray Place: Tokyo, Japan Date: February 17, 1993

[Note: Mr. Kataoka speaks in Japanese, and his words are interpreted by Hirotoshi Okamura, Manager of the Patent and Legal Department at Alps Electric. Also present at the interview was Professor Yuzo Takahashi of Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology.]

Starting a Company in Postwar Japan

Aspray:

I want to find out what you attribute to be the factors that allowed your company to be so successful as a start-up after the war.

Kataoka:

I graduated with a degree in mechanical engineering from Kobe University. Then I entered Toshiba Corporation in its communications department. That was in 1937. After nine months of experience with Toshiba, I went into the military service. I served in the military for five years and ended my service as a lieutenant in the wireless communications troop. In 1943 I rejoined Toshiba. On August 15, 1945 — that was the last day of the Second World War — I left Toshiba.

Aspray:

Why was that?

Kataoka:

Toshiba was too big for me. After I left Toshiba, I assisted with a friend's company for a short while. Then, I established this company on November 1, 1948.

During my time with Toshiba, I was in charge of certain machine work as well as making variable capacitors and switches, which were designed for use in the radio transmission systems of airplanes. Based on those technologies, which I learned at Toshiba, I started to make rotary switches and variable capacitors at my new company. Five years after I established this company, black-and-white TV manufacturing began in Japan.

Aspray:

Was it difficult at the time to start a new company?

Kataoka:

Yes. At first, I had financial troubles. Japan was in a severe economic depression at that time. Also, the electronics market was small then. Companies such as Toshiba, which now have very large operations, were still relatively inactive due to the depression. Such companies were engaged in the process of deciding how to develop and expand. My only customers at first were amateurs, who were making radios by themselves. So, it was indeed a very small market.

Aspray:

Was it difficult to build these technologies, these switches and resistors?

Kataoka:

From the technological standpoint, it was not so difficult to make those types of products, but the market was very small. As a result, I encountered much difficulty from a business point of view.

I experienced severe business obstacles for about three years, but then the Korean War started. That helped my business a great deal. Let me explain. At that time, we had radio broadcasting services in the private sector, but we did not have any such broadcasting which used shortwave. That was only used by the military services.

We had many Koreans who were living in Japan at that time, and they were quite eager to listen to radio broadcasts originating from Korea, Seoul or Pian Yang. They liked to use shortwave to receive information about their home country from Korean broadcasting systems. Those Koreans were just waiting to buy our components to make shortwave receivers. By serving the Korean people, we were empowered from a financial and technological standpoint. Building on this foundation, I decided to start manufacturing TV tuners. This product was quite new to us and, I think, also new to Japan.

TV Tuners and Motorola

Kataoka:

At that time I said, "If we are only making so-called discrete-type components, we do not have any future." So I decided to manufacture TV tuners.

Aspray:

That is a much more difficult technology than the ones you had been producing before. How did the company manage the increase in technology?

Kataoka:

The introduction of black-and-white TV was quite new to the Japanese electronics industries. At that time, there was little or no basic technology for such a TV. Because of that lack of technology, we were struggling to determine appropriate specifications for the TV turners.

We started to do business with Motorola as well as doing our business with Japanese electronics manufacturers. During the course of our business with Motorola, we learned and progressed a great deal from a technological standpoint. We already had previous business with Motorola for other products, but then Motorola also began to give us orders for tuners. At that time, Motorola gave us a great deal of assistance.

Previously, TV set manufacturers made their own tuners, and their tuner specifications were not available to us. However, Motorola provided us with such specifications. If I remember correctly, Motorola gave us test equipment to use that cost more than $100,000. We are still grateful to Motorola for this assistance.

In 1957 I was sent by Japan's Productivity Center Institute to visit the United States. They sent members to the United States for study, and I acted as secretary to those members. I stayed in the United States for about fifty days and visited fifteen factories. The United States Government and American companies supported this endeavor and gave me the chance to understand the current status of American factories. I had access to those companies — to see their facilities and to engage in discussions about their business.

Aspray:

Those circumstances were very different from a later period of time.

Kataoka:

What do you mean?

Aspray:

Later on companies were more protective of their factories.

Kataoka:

It is my opinion that the United States changed its attitude regarding Japan and the electronics industry. The United States and Japan had a long-term relationship with the United States acting as teacher and Japan acting as student. The Vietnam War proved to be a turning point. After that, the United States concentrated almost exclusively on the military industry and forgot about the consumer electronics industry.

Aspray:

I have a couple of questions about the Motorola relationship. Do I understand correctly that Alps was producing the tuners not only for the Japanese market, but also for Motorola's entire market? And secondly, what do you think were the reasons that Alps was chosen? There were manufacturers in many different places. Why select Alps?

Kataoka:

The answer requires some explanation of our relationship with Motorola. In the very early part of the 1950s, RCA and General Electric had purchasing offices in Japan. But Motorola was looking for the same opportunity to start business in Japan. So Motorola decided to follow IBM, NCT, GE, and RCA by opening its own office here in Japan. They established a purchasing office in Tokyo in the early part of the 1960s. Our company sold switches and variable capacitors to this office, but those were basically used for radio sets. Because of the differences in the measurement systems of the United States and Japan, it took about two years to get final approval for Motorola to use our TV tuners.

Aspray:

Within the company?

Kataoka:

Yes. I have very memorable stories about my dealings with Motorola. At that time, the purchasing director was Mr. O'Brien. Unfortunately, he has since passed away, but we became very well acquainted back in those years. I had tried to get approval for our tuners from Motorola for two years, but finally I decided to give up. I contacted Mr. O'Brien to convey the message, "We simply give up." Mr. O'Brien told me that maybe we were running the equivalent of a three thousand yard race, but we were approaching yard number 2999. He said that we had only one yard left to go. Why not try to complete that last yard? Mr. O'Brien then lent us test equipment of Motorola that cost about one hundred thousand dollars to help us overcome correlation problems and make quality tuners.

At that time there was no good measurement or test equipment for high-frequency products, e.g., television tuners and so on. Another obstacle was the difference in the measurement systems. Your system was being measured in inches while we were using the metric system. This caused us further difficulty.

At that time, however, most Americans had no bad feelings toward the Japanese. Americans were very open-minded and helped me very much. That time was probably America's apex.

Aspray:

I take it that the tuner business expanded and there became other customers in Japan as well as in the United States.

Kataoka:

The tuner business was indeed expanding, but at that time most of the Japanese TV manufacturers were making TV turners by themselves — through in-house production of the tuners. From our company standpoint, business had not expanded in that area.

Areas of Growth

Aspray:

What were the major products at the time?

Kataoka:

Switches, mainly rotary switches. And variable capacitors.

Aspray:

So it was a continuation of the original business of the company.

Kataoka:

We had the number one share for those product areas. Those two products, rotary switches and variable capacitors, helped our gross sales and profits. In other words, those two products were our core products.

Aspray:

By the 1950s, there must have been a number of other competitors in Japan in these businesses. What allowed Alps to have the number one market share in these areas?

Kataoka:

As far as the rotary switches are concerned, we did not have any real competitors. As for the variable capacitors, we had at least twenty competitors. Most of them were making variable capacitors for radio receivers. The introduction of the superheterodyne circuit for the radio receiver probably occurred in the early 1950s. At that time, we were making variable capacitors of the same high quality that was necessary for airplane radio transmission equipment. So, our high quality variable capacitors were very much suited to new products such as the superheterodyne circuit.

Aspray:

Where did the business go then?

Kataoka:

After that came UHF tuners. We started our UHF tuner business in 1962 and two years later, we concluded a technical assistance agreement with General Instruments Corporation (GIC). We were able to introduce technology from GIC. Around 1962, through legislation passed in both houses of the United States Congress and FCC rulings, all tuners needed to carry all channels. From that point on, in other words, all tuners exported from Japan to the United States had to have two functions: VHF and UHF.

Aspray:

Were the Japanese manufacturers ready to provide that product right away?

Kataoka:

No. Around that time in Japan, no TV broadcasting services were using UHF channels. Therefore, no one was prepared to manufacture UHF tuners. Fortunately, UHF technology was based on the variable capacitor. Initially, only Alps was in a position to manufacture such UHF tuners.

Aspray:

In order to do this, did Alps need to build new factories, hire new kinds of specialized engineers, or start a research and development operation?

Kataoka:

Yes. Japan did not have any technology regarding TV's or tuners, so we had to learn these areas by ourselves. In the 1950s most of the Japanese TV manufacturers had some quality factory engineers and mechanical engineers for TV's.

However, there was also very big support, as I mentioned before, provided by Motorola and General Instruments. Before that, the most helpful company to the TV business in Japan had been RCA. They helped Japanese TV industries very much.

During the 1960s the head of RCA's Tokyo office helped the electronics industry in Japan. He gave us three principles which have been applied to Japanese component manufacturing ever since. First, quality. Second, delivery. Third, cost. Still we continue to adhere to these principles throughout Japanese component manufacturing. RCA also granted us a patent license for TV technology and provided us with technical assistance.

Aspray:

How did the business expand from that point?

Kataoka:

We started a business here in Tokyo at this point. This building we are now in used to be a manufacturing facility. In 1960, we expanded and built our Yokohama plant. At the Yokohama plant we had, at the most, 2,500 people. Starting in 1964, we started to build more factories in northern Japan.

Aspray:

Why was that?

Kataoka:

At that time, areas in northern Japan were not yet industrialized. They were basically agricultural in nature. However, there were many high quality laborers there. Young people in these areas did not desire to enter the agricultural business and were moving from northern Japan to Tokyo.

Until 1964 or 1965, industries tended to locate in urban cities: Tokyo, Yokohama, Nagoya, Osaka, and Kobe. But, around that same time, businesses started to shift the location of their production facilities from the cities to local, rural areas. As for us, we were growing at an annual rate of more than twenty percent. By the 1970s, we were able to completely shift our production facilities to northern Japan.

Aspray:

I assume that land was less expensive there and it was also more available so you could expand if you needed to.

Kataoka:

Your assumption is correct. Another main issue was capital. In the 1960s, most of the component manufacturers started to list their shares on the stock exchange market to raise funds from the open market.

Going Public

Aspray:

So the company had been private before this and then it became a publicly held company?

Kataoka:

Yes, I think that it is quite important point to understand Japanese component manufacturers from the viewpoint of capital. According to my past experience, most of the component manufacturers all over the world at that time were privately held companies and family-type operations.

Most American components manufacturers were advanced very much ahead of any other country's component manufacturers. When I visited the United States, I saw some big component manufacturers which entered the stock exchange market. I learned the American component manufacturers' way of operating business in terms of how to raise funds from the market. Because I had a shortage of money, I decided I would also open our company shares to the stock exchange market. Today 80% of electronic components are manufactured by component manufacturers who are listed on the stock market.

When we started the business, we had insufficient technologies, so we had to introduce technologies from the United States. A second issue was capital and entering the stock market. When we became a publicly held company, we could get money from the market. Using those funds and the American technology, we were finally able to expand our business.

In the early part of the 1970s, most Japanese component manufacturers were recognized worldwide as very large manufacturers. American technology was still very powerful, and most Americans could not see that in a short time Japanese component manufacturers and electronics manufacturers would become huge, affluent companies.

Just ten years ago, I began questioning my American friends, all executives in American corporations. "You taught us so many things. For example, you told us the first priority should be quality. But you didn't apply your principles to your operations." So I ask, "why?"

Aspray:

What answer did they give you?

Kataoka:

They agreed with me. In my private opinion, what causes the disparity between their indicated agreement and their actual behavior is that American executives and their corporations are driven by short-term output goals. In contrast, most Japanese companies focus on long-term solutions and goals. Another factor is that Japanese companies have followed a system of lifetime employment and have traditionally maintained the same management personnel for many years; in this way, Japanese companies try to be, in a manner of speaking, eternal. In contrast, American companies often have personnel changes at the executive level. Sometimes this causes difficulty in negotiations.

Aspray:

I understand that the company changed its name in 1964. What was the reason for that?

Kataoka:

At that time, I had relations with Motorola and relations with the General Instruments sales force. This is very funny, but some people who speak English cannot properly pronounce my name, Kataoka; they pronounce it "Carioka." Someone pointed out that we had a very good trademark, Alps. So, why not just use Alps as the company name instead of Kataoka? I agreed. I was lucky because we were successful in registering the name Alps all over the world.

Aspray:

It just happened to be free.

Kataoka:

That's right.

Company Growth and Employee Training

Aspray:

How did you manage such tremendous growth in the 1960s? What were the management challenges to sustaining that growth?

Kataoka:

I had experience with Toshiba working for a huge organization. I also had experience with the military's large structures and organizations. I was lucky to bring those two experiences to this company.

I have also been looking at three companies over the long term: Motorola, General Instruments, and Nortronics. Only Nortronics is still making magnetic heads — even though Nortronics was purchased by an American company. I could learn from those three companies and their very powerful American engineering activities.

Twenty years ago, I established one building called the Alps Training Center with the understanding that it was mainly for Alps employees who were university graduates. They could learn many things there even if such knowledge may not be directly or immediately applicable to our business. I decided to give them the opportunity to acquire more skills while working for our company.

Aspray:

What kinds of topics were taught in this training center?

Kataoka:

Mainly we provided training on management skills. We were also training instructors in this area. We then sent those persons to instruct the divisions throughout our company's operations. These instructors could then discuss our policies with persons who are working in our many divisions.

In the past ten years, technology has advanced very rapidly. In order to sustain the rapid transfer of technologies, we also decided to send our engineers to laboratories or institutes controlled by professors to exchange information and to have coordinated activities at the university level.

Aspray:

I don't know much about the Japanese system. In order to go to the universities did your company have to supply equipment or funds to the university to get knowledge?

Kataoka:

We did not spend a significant amount of money, and we did not give universities any kind of equipment. However, if a group within the company engaged in activities under certain professors, then those groups needed to support such professors from a financial standpoint — perhaps through small donations.

The government promotes decentralization of industrial activities outside of Tokyo. So the government provides support to establish certain technical coalitions. For example, we have been working together on R&D activities with Tohoku University to develop technologies.

Sometimes Americans may misunderstand these situations, but they must understand that Japanese private companies are not directly supported by the government. The technology policies in the two countries are quite different. We are just following the government policies for decentralization. We work together with the universities and local governments.

Challenges to Growth

Aspray:

Coming back again to ask a little more about this rapid growth, it seems that you faced a whole series of challenges. You want to have enough factories and personnel to be able to expand, but you don't want too many so you can keep your overhead low. You have people rising rapidly in the company but maybe they go too high, beyond their talents. You have problems with your suppliers, and so on. Can you give any advice about other lessons that can be learned from your experience here at Alps?

Kataoka:

We are always having small troubles, or big troubles because we are managing a large technological company. I can explain some big troubles which occurred during my management. In 1974, when we had a depression in Japan, we asked 3,000 of our 11,500 people to leave the company. Roughly 30% of the people were asked to leave. As you know there is quite a big difference in the employment systems of American and Japan. We have been practicing a sort of lifetime employment system. Labor here is also somewhat protected under the law. In the United States, it is much easier to lay off people. But in Japan we could not reduce our work force so easily.

A second big problem was the appreciation of the yen. For example, many fluctuations occurred in 1979.

A third major problem is one we are currently having. We are currently facing recession. It is the same all over the world. In Japan, we call it the collapse of the bubble economy.

Aspray:

Did going off of the gold standard cause a problem for you?

Kataoka:

Yes. When we started business, there was a fixed exchange rate of 360 yen per U.S. dollar. With the fluctuation, our business is made more difficult. Now the exchange rate is approximately 120 yen per U.S. dollar.

Competitiveness in Japan

Aspray:

At some point did Alps become the supplier of components to the large Japanese manufacturers of systems? When did that happen?

Kataoka:

In the middle of the 1950s — either 1954 or 1955. The EIAJ (Electronic Industries Association of Japan) has been keeping certain industrial records on growth by companies. Alps' annual growth was consistent with this industry data until recently. Recently, Alps' overseas production has increased, and such production is not reflected in the EIAJ data. As a result, the EIAJ data must be adjusted to reflect reality.

Aspray:

It seems to me that Alps has been extremely successful in secondary manufacturing, component manufacturing. There are fundamental tensions there because the systems manufacturers who buy your components have a great deal of power over the companies. How was it that Alps was successful? What strategies did they use to make sure that they could continue their growth and profitability while they had to deal with these powerful companies that were much larger than they?

Kataoka:

We have been upholding the principles suggested by the head of the RCA Tokyo office, as I told you. Number one should be quality. Second should be delivery. Third should be cost. We have been relying on these principles very much. We do not primarily manufacture products according to the drawings given by manufacturers. Instead, we mainly generate such drawings, and make products according to our own designs.

Our engineers work in close cooperation with the manufacturer's engineers, so we have close communications with their engineers. It is true that our customers are very powerful. Intermediate between systems and component manufacturers, we have a formal organization called EIAJ (Electronic Industries Association of Japan), as I mentioned before.

Each company also engages in very useful, regular, informal meetings with key members of its suppliers. We call these cooperative group meetings.

Set manufacturers also belong to certain organizations. In those organizations, most of the component manufacturers are invited as members, so that we can exchange our opinions.

Aspray:

Does the industry organization have any real power or are they just a persuasive body?

Kataoka:

The ultimate power resides in each individual company. By using the organization EIAJ, however, we can submit our companies' opinions. Under the aegis of EIAJ, we have at least three hundred committees in which we discuss technical issues and other relevant issues. I formerly was the vice president of the EIAJ. I was also the chairman of the component committee within the EIAJ. Through these organizations, we have good communications with our customers, i.e., the big manufacturers, and they will listen to our opinions. They may not always change based on our opinions, but at least they listen.

Your government and also the leaders of American corporations have said that Japanese companies have Keiretsu. Do you understand Keiretsu? In my opinion, this is not true. We are living in a free market, and we are in a very competitive situation.

We have been dealing in this industry by using our own processes and technologies. But, we do have some group meetings to assist us in communicating with our customers. These are associations of suppliers sponsored by the suppliers' customer. These associations basically consist of assemblers, discrete component manufacturers and raw material suppliers. In fact, we have several competitors within these same group meetings, and we have very free exchanges of information both horizontally and vertically.

At this point, I would like to mention that I believe there is one big difference between various industries. That is the life cycle of the industry's products. In the automotive areas, the cycle is five years. But in our industry, electronics, it is only one year. Because of the long life cycle for products in the automotive industry, this can lead to some very close R&D activities between auto manufacturers and their suppliers. When Americans look at these activities between auto manufacturers and suppliers, they regard those activities as inappropriate. But in my opinion, that is a misunderstanding of the activities.

We do have business with auto manufacturers, a dashboard business. We have been supplying BMW in Germany with certain air conditioning control panels, and now our product will be used for the 1995 model year. We are still in the development stage at this time.

As you know, Alpine Electronics Inc., a subsidiary of Alps, has business with Honda. At least twice a year, Alpine and Honda have big technical meetings where the discussion is on products to be sold two or three years into the future. We are not discussing current products. Further, despite these long-term discussions, Honda is not obligated to use our company for future activities. If those discussions fail, our activities in two to three years will all be destroyed, because Honda might choose to use another supplier. In my opinion, most American companies are discussing Japanese companies' activities by looking only at the very nominal or surface appearance of these activities.

Diversification and New Markets

Aspray:

Business theorists say that one of the strategies used by components manufacturers is horizontal diversification. That is, you take the component you are manufacturing and start broadening your line so that you don't have to rely so much on one business relationship. Instead, you have many relationships with many different industries. Was that a strategy in Alps, and did it succeed?

Kataoka:

There are two methods of engaging in the components business. The first involves acting as a subcontractor, which is making products from drawings that come directly from manufacturers.

Alps is a good example of the second. We are primarily doing business based on our own drawings and designs. Because of this, we are capable of diversifying our business. We are expanding the business in various ways. For example, we have added components within the automotive product field.

But we are not increasing the number of variations on particular components. Instead, we are trying to standardize our components so that they can be used in a diverse range of final products. The reason we can do this is that we are doing business according to our own designs.

We used to have more than ten thousand product lines, but recently most of the Japanese component manufacturers have tried to reduce the number of component varieties offered. For example, we have reduced from more than ten thousand to five thousand product lines to reduce our overhead costs and manufacturing costs.

When I checked the code numbers for our products, the code numbers were based on the customers and their products. But there were still over three hundred thousand. That is too many. So we are now trying to reduce those numbers even more. We would prefer to reduce to half of these current figures.

The reason we have had this large number of products is that we were following improvements in integrated circuits. The newer integrated circuits allowed for down-sizing, and we ended up with so many tiny products.

Aspray:

Can you tell me about some of your new businesses of the 1980s? I know, for example, that you have become a major manufacturer in floppy disk drives and computer printers. Could you tell me how you got into that business and how it grew?

Kataoka:

We started the floppy business with Apple Computer first. We established our own technologies to make thermal transfer printers. Then we built our market by developing those technologies. The application has been mostly for word processors. Actually, we made dot matrix printers first but we gave up because we were not successful in that business.

Aspray:

In most cases were the floppy drives sold to a systems manufacturer? Were they then put into somebody else's machine?

Kataoka:

Yes.

Aspray:

Has the company tried to get into primary manufacturing, to produce finished products? Has that been a goal of the company?

Kataoka:

We probably have the technology to make a complete set of products, but in my opinion, we do not have any sales power to send those products to the market. We established Alpine to send products directly to the customers in a specialized market. Alpine's main business is in specialized products for use in automobiles — especially with Honda and other auto manufacturers. Alpine is successful in the automotive business. But is is quite a different situation when you get into general components manufacturing.

Lessons for American Industry

Aspray:

Yes. It just seems so totally different from the kind of business you have been in. Are there any parts of your business that we have not talked about that you would like to mention to me?

Kataoka:

No, but I do have several additional comments. First, I would like American management to return to their old style of corporate management. They used to give so many things to Japanese industries. So we want to know, "Why don't they remember the past, and come back?" There have been no U.S. manufacturers of radio sets, color TVs, VCRs, tape recorders, and video cameras for some time. Even if engineers graduating from the university want to get into this market or these technological fields, there are actually no openings for these engineers in the United States. They have nowhere to go.

Second, American industry should keep a very close eye on Asian countries and in particular on mainland China's activities, especially the labor force and the economy.

I have these two points for the Americans, and I have constantly been telling my American friends these two points. In my opinion, it is not best to attempt to solve problems through discussions with government bodies.

I should also mention labor issues in the Japanese electronics industry. Of course, we have some experience with labor issues, such as strikes and other action the labor union has taken against the company. But the electronics industry as a whole thus far has had a very good relationship with labor. In my opinion, that will not be changed in the future. In the future, I believe labor will not be an issue for the electronics industry, because the thinking by most top management personnel at these electronic companies parallels the thinking of those leading the labor unions. Each side understands that it must grant concessions. So, in my opinion, the heads of the labor unions will continue to have a small role in the future.

I believe that the Japanese electronics business has learned many things from the United States electronics industry. When I visited a person from General Motors who has studied manufacturing methods, I mentioned that we have learned so many things from the United States and that Americans should do the same from our operations. To promote such study, we opened our factory to a delegation from General Motors.

Okamura:

Mr. Kataoka has shared this opportunity with a total of eighty young engineers and middle managers from General Motors. I think he has also been contributing, not only to the company, but also to industry and to Japan itself. In fact, he was honored by the government and received the Second Class Order of the Sacred Treasuries in 1983 because of his contributions to Japan's industries.

Aspray:

Very nice.

Okamura:

In my opinion as an associate of Mr. Kataoka, he has contributed so much to the company and also to the electronics industry. He learned many important things during his time in the United States under the Japanese Productivity Institute. He saw that so many American component manufacturers were corporations which stood independent from the systems manufacturers. He took this concept and reasoned that Japanese components manufacturers could also survive in the market as independent manufacturers.

He misses his friends in the United States. Most of his closest friends are retired from their companies or have moved away. Mr. Kataoka said that throughout this interview he has been experiencing some nostalgia for the past. Only one person is still active in the industry, Mr. Galvin from Motorola.

Aspray:

Robert Galvin, yes.

Katoaka:

Now our company is operated by the second generation of management, and I am now half-retired. [Chuckling] There are very few persons who can speak about the background and origins of this part of the electronics industry. I am one of the few remaining persons.

Aspray:

Yes, indeed. Thank you.