Oral-History:Robert Galvin

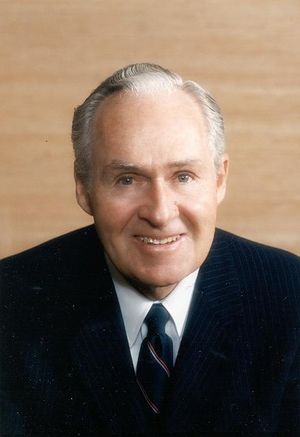

About Robert Galvin

Robert Galvin was the chief executive office of Motorola for thirty years. Although he was not trained as an engineer, Galvin successfully managed the company for a number of decades with his ability to think differently from engineers and to push them further. The interview provides general ideas about Motorola and offers various anecdotes related to training and manufacturing.

In the interview, Robert Galvin tells about why Motorola has been extremely successful in the international as well as domestic market over the last few decades. He also discusses how technical knowledge is represented in Motorola’s senior-level management. Galvin emphasizes education and formal schooling to maintain sustained growth for the company. According to him, the engineering-trained personnel can benefit from business experience and training. However, Galvin claims that formal training people can have in universities is adequate only partially and that is why Motorola created their own class of thoughts for training. Another reason for the success is the company’s devotion to quality issues and consumer service. Galvin explains how the company coped with the Japanese dumping during the mid-80s and what kind of benefits Motorola have received by having a diversity of customers throughout the world. The interview concludes with the two questions of investment and military-industrial relationships at Motorola.

About the Interview

ROBERT GALVIN: An Interview Conducted by William Aspray, Center for the History of Electrical Engineering, April 14, 1993

Engineers as Executives Oral History Project: Sponsored by Center for the History of Electrical Engineering, The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc. Interview #152 for the Center for the History of Electrical Engineering, The Institute for Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc.

Copyright Statement

This manuscript is being made available for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the IEEE History Center. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of IEEE History Center.

Request for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the IEEE History Center Oral History Program, IEEE History Center, 445 Hoes Lane, Piscataway, NJ 08854 USA or ieee-history@ieee.org. It should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user.

It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows:

Robert Galvin, an oral history conducted in 1993 by William Aspray, IEEE History Center, Piscataway, NJ, USA.

Interview

INTERVIEW: Robert Galvin

INTERVIEWED BY: William Aspray

PLACE: Motorola Company, Schaumburg, Illinois

DATE: April 14, 1993

Keys to Motorola's Success

Aspray:

Perhaps the best way to start is with a very general question. Motorola has been extremely successful over the last few decades. Can you isolate several elements that you think differentiate your company from your competition? Or at least ones that are the keys to the success of the company.

Galvin:

I'll start to develop that list, but I cannot do it in an orderly way with a hierarchical rating of these factors. What success we've had, I think, is a function of a culture of a very significant involvement on the part of We, W-E. It is not the function of one engineer or one or two people that have done a particular thing. It's a fairly broad spectrum. This has been helped by a spirit and a drive at the top of the company that we should leave relatively no stone un-turned. Therefore there has been a high spirit of risk and commitment to what needs to be done on the part of the we's.

So we've had a very substantial number of people who in their field — whether it's semiconductors or radios or automotive controls or what have you — have had ideas as to what we could be attempting to exploit. We try very hard to support a very high majority of those things. Neither of those two factors would necessarily distinguish one company from another, except to the extent that the increment is truly different between this company and the other company. I would be inclined to guess that there has been a difference because we devote so much time to both of those factors. So we have the energy of many, and we have the continuing admonition: Are you sure you've told us everything that you want to tell us that you want to try? We still have to cut some things off at the bottom line.

We have an expression here that is illustrative of that, and it goes back many, many years to when we established a program called the Technology Road Map. That, too, is not so different from a lot of other people, except when we started it we didn't know of anybody else that had one like it. A road map is indeed a road map. But the road map ends up by putting, in effect, destinations and routes on it, technical destinations and routes. One of the things that we encouraged was that there would be a more than adequacy of minority reports. Once you and I have elected to support what was to be on the road map, then we'd go back and say, "Who didn't get heard?" Or "who got lost from being identified?" Then that gave us another iteration; since maybe we had been too short-sighted. What I'm attempting to do with these factors that we're talking about here is to identify factors that are absolutely relevant to the engineering community.

Also we want to find some other more general factors. We've tried to practice high integrity with the customer, for example. These are also probably distinguishing factors if indeed any company does them incrementally differently or better. But those are two factors (WE, reach out risk) that caused Motorola to have a pretty generous share of new products coming along or to be among the first to market these products. Then it's been within that environment that the professionals have done — compared to what we did in prior years or decades — superior jobs in identifying the spectra, specifying what they wanted to design and readying them for production. There is also the manner in which our scientists and engineers have teamed up better than they did before with all the other functions of the institution.

So, in summary, I think it's a case that we have done a rather good job of seeing to it that all the influentials had a firm voice in what we ought to be doing. We kept encouraging them to look for more, and letting them know that we could support them. Then they have put process alongside of intent, and they have performed quicker, better, moved earlier into production, provided better yields, all those things.

Nature of Technological Business

Aspray:

This sounds like good advice for any kind of company. Whether you were running a service business or a product business, and whether it had to do with technology or not, those maxims that you've suggested would apply. What is it especially about being a technological business?

Galvin:

I guess I would emphasize that I think what I have said was intended to be distinguishing of a technology company because we have tens of thousands of engineers, and they have technology anticipations and preferences. We search high and dry throughout our technical community to make sure that the best idea for a totally new function to be accomplished by our technology or a radical change in the improvement of that function is one that we are aggressively investing in in the laboratory.

Incidentally, we engage in probably as much self-development, teaching, of laboratory people as some in the business do, and a lot more than others in the business do, on the assumption that all engineers — I'm not an engineer, but those who would be — can get much better at what they are doing. We are not satisfied with our apparent rated ability to design, and we are sending our people to school and urging them to do all manner of things that have to do with improving their process of development.

We currently have in vogue an organized attempt to change the rate at which development programs will go from initiation to exploitation, and we are following all manner of particular processes that will cause three, or ten, or twenty engineers to be able to effect their work at twice the speed, or ten times the speed, depending on the nature of the class of work, compared to how they used to do things. We're looking at goals that used to take thirty months, and we now want to do them in three months. I think they are all doable in due course. So we are teaching ourselves to run laboratories with higher intensity of expectations of what we can aggregate, with the expectation that we can do a lot more things, and do each thing with much greater dispatch.

Technical Knowledge and Management

Aspray:

You say that you yourself are not trained as an engineer, but what kind of knowledge do you have to have in senior management of technology to be able to make appropriate decisions?

Galvin:

Let me tell you an anecdote. It will illustrate my point. I've received one compliment in my life — I don't receive very many and shouldn't — but one of our senior people, who is an engineer and who is moving toward retirement and has never had to worry about what he said to me, said, "You know, we're very lucky we've had you as the head man of this company for a number of decades." I said, "Okay, I know you've got an angle. What's your angle?" [Laughter] He said, "We were lucky you weren't an engineer. If you were an engineer, you'd probably have known some of the reasons why we were pretty sure we couldn't do what was tossed out as a speculative thing. You kept believing we could do it, and then we'd have to go off and try to do it, and we'd discover we could do it."

I think what a person like myself can contribute, if one has had the experience (and I have had decades of experience making these judgments), is that one learns to measure the capacity of an institution or cadres of people in it. You learn to bet on good folk, and lots of companies have good folk. But I would bet a little stronger on many of our people than sometimes they would bet for themselves, and often enough they would prove their capability. All I was was an expresser of hope or faith in them, and trusted they would get it. Forgive all those apparently soft words. They are very powerful words. We deal with a sense of confidence and dependence on each other. If each one of us reaches out a little harder and finds that we do have that extra capacity, I think that's one role that someone like myself plays.

Aspray:

How is technical knowledge represented at the senior level? Is there a particular person representing the laboratories, say, that is on a senior management team?

Galvin:

In our company the overwhelming majority of people who are in leadership roles are engineering-trained. During the longest tenure of the chief executive office — while I was in that role, and I held it for thirty years — during all of that time, there was always an engineering-trained person in that office with me. For the last fifteen or so of those thirty years that I was the chief, two of them were engineers. They were superb engineers in their practicing days, and one of them until this day. He is still a vice chairman of the company although not in the chief's office. He was probably as acutely tuned to today's technology as even our younger people. He couldn't design the last micron of specification on an integrated circuit. But he would be able to evaluate substantially what the very bright young engineer may be explaining. So we have that engineering knowledge proliferate throughout our institution. When I was active in the direct management of the company, I would be rubbing shoulders with these people every day. So I picked up a lot of technology by osmosis, and then I did my own extrapolations from that in terms of my expressions of confidence. We did have to talk the language, and I'm able to talk the language and estimate what's going on, though I could never lead an engineering activity.

Education of Engineers

Aspray:

For those people who come up through an engineering track, do you feel there's a value in either placing them in positions where they get business experience or getting special training on the business side? Business school or continuing education?

Galvin:

The answer is yes. Organizations go through stages or eras, and during the first fifty years of Motorola's existence — we're 65 years of age — most of that was accomplished by experience. If you were a very bright young engineer, and your product line was doing well, we saw to it that you had considerable interface with customers. You discovered there were a few things that weren't strictly engineering that helped the engineering result to be translatable. You learned to become a business person as well as a technology person.

We've been transitioning into a new pattern. Today we recognize that as our growth rate, which continues at roughly fifteen percent a year, begins to require very large absolute numbers of growth every year — fifteen percent of ten billion is 1.5 billion, so we're creating $1.5 billion worth of business every year, and pretty soon it'll be $2 billion worth of business every year — means more people have to accelerate their ability to have the general influence as well as the technical influence. So today we are moving towards having to substitute some experience with a scholastic effort of some kind: going to an outside school, doing a great deal of inside training, training on technical subjects as well as business subjects, and training through role modelship.

If you are a leader and a good role model, you alert staff to try to recognize their strengths and weaknesses and work on them through formal schooling. As a matter of fact, we are now having to move in a more formal fashion to accelerate people's attention to knowing the generals as well as the specifics. The specific is the technology. Our election in this regard is very simple — I think it's the same election almost any other company makes — that you can't take very many general people and cause them to be very good at technology. But you can take people well-trained in technology, and they can become generalists. We have a great deal of confidence in many of our people being able to do that. But we try to be selective and not interfere with, let us say, your technical potential, if indeed that is even more rewarding to you or is more beneficial to the company. So to the extent that we can each play our selective role, mutually we try to decide which is best for both of us, the employee and the company. But if being a generalist is the destiny of an individual employee, we have to provide a great deal more formal training.

Aspray:

Do you find that the kind of formal training that's available outside of the company in universities, say, is adequate to the needs of the company?

Galvin:

Only partially. To the extent that the engineer has had very little experience in knowing the principles of marketing, there are excellent things that can be taught in that regard. If one were to wish to focus on the issue of international culture, many, many things are offered at the university level. But ironically, the most important class of subject to us is not available in the university, and that is all of the aspects of things that come under the rubric of quality. Universities never did anything — that's almost an accurate statement. There probably are three, four, five — counting on one hand — universities that have done some original work on the subject of quality prior to 1980 or 1985. And few had even done anything by 1990. So we had to create our own class of thoughts, organized ways of thinking and doings about quality, and have had to teach that to ourselves. We had to actually teach the vocational skills, and we had to teach the attitudinal judgment class of factors. That has been an immense void that we have had to deal with. I think we have dealt with it rather skillfully.

Speaking again to your first question, that would be, I think, a distinguishing feature of Motorola; that most companies have not gone to the extent that we have to sit ourselves down and say: "You are a factory manager; you must learn all these processes and procedures and concepts. You are an engineer; you must learn all these processes and procedures and concepts. And you must use them." They can be used in some reasonable self-directed way. But the principles are pretty straightforward and are objectively proven as being worthwhile.

Quality and Customer Service

Aspray:

Every company today pays homage to quality and to customer service. But it seems from everything I've read about Motorola that it is different from many companies in that it really takes quality seriously, and has been able to implement this concept effectively in the company. Can you speak to this issue?

Galvin:

Yes. I think your observation is fair — valid — and would not be exaggerated for us to confirm it to you. There probably are fifty or a hundred companies that have applied a devotion to quality. Just to mention a couple of them, I think the Milliken Company is certainly such a company. Xerox is very close to being that kind of a company. Then there are other companies that have been coming along in this area, such as Procter & Gamble. Parts of AT&T have embraced it very substantially. Texas Instruments is coming along rather well. I'm sure I'm leaving out some that deserve to be mentioned, but we'd be hard pressed to carry this part of the conversation on very long.

We have placed an inordinate devotion in quality. The reason that we have succeeded, I believe, is that everybody who could be an influence, and that started with me but it continues with our present chiefs and lots of the other main players, have embraced the proposition that quality is the first item on every agenda. I don't mean that in the sense of writing down a ledger of subjects for a ten o'clock meeting. But it's the first issue. We hardly ever start anything without saying, "what about the quality?" We are even that pedantic about it, if necessary.

Aspray:

I see.

Galvin:

We'll say, "let's talk quality first." As a consequence of that, all of the sub-pieces end up having to be addressed. So our people are addressing quality issues at all times: in design, in designing for manufacture, in being able to manufacture what's designed, and all those kinds of interrelated factors. There's no place in the company where it doesn't get superior attention, whether it's personnel or accounting or any other of the so-called "soft" subject functions of an institution. It is everywhere in the culture. If there was an engineering department that were to prefer not to be burdened by this, they would be surfeited by everybody around them — all of whom were practicing it inordinately.

I think we're also doing something that is helping to complement that a little better than a lot of other companies. We have long been a participative management-oriented institution, starting back in the late 'forties, and we've muddled along for a long time learning what it all meant. But the culture, the roots, kept getting deeper and deeper in the 'fifties, 'sixties, and 'seventies. Now the thing that the world refers to as "teaming" or any other words that are metaphors of that, these are things that are second nature to us, including very many engineering teamings. Our engineering teams, as a function of the things they will study, are coming up with seminal concepts of how to design, not what to design. Seminal concepts of new procedures to engage in in the laboratories. We are trading those ideas among a lot of our people. So with the culture of participation, teaming, and all the other relevant words that again are on the lips of a lot of people, it is ingrained here — it is a very natural practice among a gigantic majority of our people.

Quality Metrics

Aspray:

You mentioned the soft parts of the company where you also wanted to implement that. It requires, in a way, being able to quantify — or at least codify. How did you go about doing that?

Galvin:

Early on, in the generic objective of our having a quality program, our people learned or conceived things — I'm sure they mostly learned from somebody else to begin with, but then they augmented or incrementally conceived things that were better — that satisfied the objective that we were going to have to have very substantial metrics. The word "metrics" was not a commonly used word in Motorola in 1980. It was a very commonly used word in 1985. By metrics we meant, "measuring everything." In particular we measured in cases where something was not up to snuff, a defect. Anything that isn't right is a defect. We adopted the heresy that it was well to have a proliferation of data. This was in contrast to the common thesis that one should have the least data possible because data will just obfuscate things, and one does not want to have to be just keeping a lot of records anyway. We keep records on virtually everything around here so that we can use that data for first-cause analysis. We are constantly flushing up for ourselves that there seems to be a problem in a particular place. A yield-linked condition or a warranty issue, all these things that relate to something that wasn't adequately designed and produced.

Early on we said, "we need an inordinate amount of data." The engineers had to keep more data, the factory had to keep more data, which all went back to the engineers. The field had to keep more data. The accountants had to keep more data on what they were doing. Let me go off on a tangent for just a second. We keep prolific data with regard to the accuracy of our shipping tickets, our receiving tickets, the receivable documents, the bills we send to our customers, which is a receivable for us and a payable to them. If we ever find one defect, a number that's out of place and it's therefore difficult to trace the paperwork, that's a condition in Motorola that we consider intolerable.

What you have now is a culture. It's intolerable to have a mistake on a piece of paper because that means the poor customer has got to go around and check all kinds of records and figure out which two pieces am I supposed to compare before I pay or I do something else? It doesn't have any value. That could very well have been because we didn't put the label on the product right when we designed the product, and that's a soft part of the design, but it annoys the customer even more than if the product didn't work when he took it out of the box. At least they'd say, "well, once in a while maybe products don't have to work. But, gee, can't you get the paperwork right?" If the culture requires that even the paperwork be right, sure as hell the engineer knows he's got to get the circuit to have a life-cycle benefit to it. All of these things reinforce each other.

Benefits of Quality to Company

Aspray:

Maybe this is a simplistic question, but in what ways does quality benefit the operation of the company?

Galvin:

It is axiomatic that in a good company, one that is operating to a good set of standards, is accepted in the marketplace, and is getting a decent share of the market, et cetera, but which does not place a superior emphasis on learning the practices of good quality, the cost of inadequate quality to that institution is probably between twenty and forty percent of sales. That is the penalty to that institution for lack of attention to superior quality — twenty to forty percent of sales. So if you have a company that is doing, let's say, $100 million worth of sales, it should be probably spending $20 to $40 million less to produce the same result. People say that's inconceivable. That is a fact. We know it's a fact by very sophisticated analysis, and anybody that's deep into this subject will confirm them. They may instead say it is fifteen to thirty percent. But twenty is an easy number to deal with. If you can cut that in half by some very conscious efforts and in ways that are evident, one starts to say, "well, that I can understand. Now you've saved me some money."

Most businesses, and even most engineers, have a propensity to actually put too damned much emphasis on analyzing what the money factors are. But if that's what gets your attention, we can use this one to get the engineers' attention or anyone else's attention in the company. The payoff from an accounting or a financial standpoint is gigantic. It's just gigantic. Before you leave, I'll give you a little sheet of paper that is quite public around here, and we give it to anybody, called the "Welcome Heresies of Quality." It is a one-pager. Have you seen or heard of that?

Aspray:

No, I don't think so.

Galvin:

- Audio File

- MP3 Audio

(152 - galvin - clip 1.mp3)

One of those heresies is YOU CANNOT RAISE COST BY RAISING QUALITY. This is saving enough to the pragmatic, traditional, business person. There are, however, more valuable, more persuasive reasons for quality. They are measured in customer satisfaction.

I sat in the corner of a cafeteria in the Ford Motor Company about ten years ago. I had spent one whole day with whomever I could visit: people that installed our electronic equipment, who serviced it, who paid the bills, and so on. I didn't see any big shots. One fellow berated me for ten or fifteen minutes about the fact that he couldn't reconcile our shipping tickets and their receivables with the payables they had. This did not add any value to the Ford Motor Company. He spent three weeks trying to reconcile this. Ford Motor was dissatisfied with Motorola. This person represents Ford Motor Company, and he was telling everybody at lunch breaks and so on that "I don't like doing business with Motorola. They waste too much of my time." When we fixed that matter and finally he had months and months of satisfactory relationship, the big value now is we have not only eliminated the complaint, but we may have somebody saying, "Oh, I really like doing business with Motorola." Well, that's invaluable. There is the greatest value of all. Whatever is the way of articulating total customer satisfaction is the really great benefit.

How does quality affect companies like ours? There was a recession, we are told, in 1992 and 1991. It didn't impact Motorola. That's an inaccurate statement. So I'll put a parenthetical interpretation in there. Recessions impact everybody because you end up with price competition that's more exaggerated, and very vigorous efforts and plans on the part of competitors who are trying to hold their position. So we have to scrap harder to get what we get. But we kept increasing our share of the market because now there was plenty of supply, and it made sense for the guy who wanted something to buy it from the best supplier. If we're the best supplier, not only best, but our quality is best...our prices don't go up because quality takes our costs down. So we get a bigger share, and we weren't laying people off in any of our businesses. Our sales were holding up, we had some growth. There was a little pressure on the profit margin, not because the quality was up, but because the other fellow was saying, "I'll practically give you my product." We had to meet a price competition. That's the American Way.

So there are gigantic payoffs, and the engineers appreciate that. It really pays off to the engineer in that, if his company's sales volume holds up, then there's the opportunity to continue to allocate whatever your percent for engineering is against that high base. So the budgets for engineering hang on. The reaction is, "Gee, I guess I'd better design better, design faster." We get to market faster, we get our market share up; we keep the sales volume up. The whole thing cycles around. You know that story very well. Our people understand that. So quality is absolutely the supreme driver as far as our company is concerned. Some people say, "Oh, yes. Quality's very good. We think highly of quality. But we think going for profit margin is very good, and we have a very special approach to advertising." Those are all good things, too. But none of them rank with quality in our estimation. In that sense we probably are rather unique in that we are biased overwhelmingly to quality being the determinant of total customer satisfaction, and that drives so many other things.

Aspray:

How does it affect economies in manufacturing inside the company?

Galvin:

Oh, gigantically. For example, if one has a perfect operation, you don't have to have any buffer stocks. So you don't have to have storage space in the factory. You don't have to have repair stations. As soon as you start to design a manufacturing operation where you don't even design space in the building for buffer stocks, you have a lower-cost factory. You don't have to have racks to put them in, so you don't have such leasehold improvements in your building. You don't provide any people for repairing the product because you have nothing to repair. You're going to probably have a more consistent demand from your customers, so you can now operate the factory a little more smoothly. Although nothing is ever totally predictable, you can tell your suppliers what their schedules are more intelligently. They say, "If you're a predictable customer, I can give you a little better price." So everything incrementally ends up being lower in cost. It's not just a case where somebody says, "Well, you've designed the product, and when it comes off the tool, this is what the material and the labor cost will be." It's all these other factors that make a five or ten or fifteen percent difference in every one thing that you do.

I'll tell you an anecdote. The Chrysler Corporation did a thing along this line when they conceived of the Technology Center. It's probably the most dramatic thing that American industry has seen in ten years. Have you been to the Chrysler Technology Center?

Aspray:

No, I haven't.

Galvin:

Do you know about it?

Aspray:

No, I don't.

Galvin:

The Chrysler Technology Center is a building, but it's also an activity, a function, and an organization in the Chrysler Corporation — built outside of Detroit fifteen or twenty miles. It's like a Pentagon. I don't think it's quite that big, but it's a big place. The Chrysler Technology Center is, in effect, a facility and an organization that permits for the total integration of the entire Chrysler Corporation under one roof. The people who think with the customer reside in that building. They go out and make trips. The people who conceive the product work are in that building. The people who manufacture the product work are in that building. There's a practice manufacturing prototyping plant in it. Et cetera, et cetera. The whole business is integrated in this one great big building. Seven thousand people.

The building cost Chrysler Corporation one billion dollars. Lee Iacocca authorized that amount in 1983, and he was criticized until it was opened last year. I happened to be the one invited speaker to come to the grand opening of their facilities, and I knew what the gigantic promise of this thing was. When I got there, Lee couldn't come and hear my speech. He was upstairs, still defending this concept and expenditure with the press. He was challenged. "How could you possibly spend a billion dollars when you have all these other problems at Chrysler Corporation?"

When it was all over, I was escorted up to Lee's office. He was sitting there with his tie open and I said, "how are you?" He said, "Oh, fine. I've had to handle the press again." I said, "Lee, I hope you were able to tell them what you and I both know is the case. The day that this facility goes on stream a hundred percent — and it's just about now in 1993 or in 1994 — everybody will be clicking; the team will have been playing, and they know what they're doing — count 365 days from that point, and you will save in that 365 days the entire price of this project, one billion dollars. Not over 25 years, but in one year. Why? Because the Chrysler Corporation does $35 billion worth of business a year." At that point in time, the cost of inadequate quality may have been $7 billion, 20 percent. Okay. Maybe it was only $5 billion. But let's say seven because the numbers are nice and easy to multiply. So I told Lee, "You will improve your operation by eliminating the cost of bad quality by at least one seventh, 14 percent of the seven billion the first year. And you couldn't do it if you didn't have this facility." So that's how it affects manufacturing, engineering, accounting, everything else.

Incidentally, it couldn't have happened without it being a design center, a technology center. It wasn't an accounting center. It wasn't a consulting business center. It must start out as a technology center because it's a technology business, making cars. We do something similar, but we do not have to do it the same way as Chrysler — because cars are so damned big. We can do something similar in pockets of our company. We have all kinds of little places like that, where everybody does everything in one room. The designs come faster; the manufacturing is lower cost.

Integration of Design and Manufacturing

Aspray:

Is there a structural integration of design and manufacturing within Motorola?

Galvin:

I guess the answer is "yes," but it's very diverse by individual pockets of businesses. There are group dynamic factors that make a gigantic difference, such as I just alluded to. Frankly, there are also disciplinary factors. In our case we have done the unique thing. Nobody else has done it to the extent that we have, namely, we have obliged each of our suppliers to promise to attempt to prepare themselves to be worthy to compete for the Malcolm Baldridge Quality Award.

That is making a vast difference with a large number of our suppliers, a lot of whom thought that was meddlesome, unnecessary, superficial, and superfluous. Once we put their nose to that grindstone and said you must be able to match the factors and criteria, the 33 of them, or however many there are, in the Baldridge Award, and be worthy to compete for it, they discovered that they had to learn some new things. Then we teach them.

Aspray:

I see.

Galvin:

If they want to come, we'll put them in our classes, and we'll teach them what they need to know to have their quality system match our quality system. Not by rhetoric, but by practice. We will teach our competitors the same principles, on the assumption our competitors will be our suppliers. Because in this industry, as you know, we compete with each other, we supply to each other, and we very often consort with each other in some honorable ways. So we'll teach anybody to follow our quality standards and processes.

Aspray:

That's very interesting. The Baldridge Award is not only a recognition of quality; it's a vehicle for obtaining it.

Galvin:

Oh, yes. It should be the national standard, and we have advocated that the President declare that. Nobody's done it yet. Maybe this President will. We're dumbfounded to see that nobody else has obliged their suppliers to do this. IBM has partially done it. Maybe one or two others. How can they be laissez faire with their suppliers if they want to be perfect themselves. If fifty percent of their parts come from suppliers, how can they be perfect if their suppliers are not put to this same challenge? As a matter of fact, by our doing this, we have given the challenge to the industry, because anybody that wants to be good supplier of the industry would like to supply to us. So it's good for everybody else in the electronics industry. In that sense, only one of us had to take that lead. But we get the greatest benefit out of it.

You are eliciting a few other particular reasons that relate to your first question as to 'what have you done different?' I wouldn't have wanted to start by saying "Well, we forced all of our suppliers to prepare to go for the Baldridge award" and have somebody think that was the kingpin or pivotal factor, but you can see what the sub-part tactics are and how they all relate to our emphasis that quality comes first.

International Customers

Aspray:

We started off on quality and customer service. We have talked mainly about quality. Are there some things that you want to say about customer service? I'm particularly interested in the fact that you're increasingly an international business, and how do you deal with your international base of customers?

Galvin:

A customer is a customer. There is no difference between dealing with the Chinese or the Japanese or the French or the Germans or the what-have-yous. It's all the same. Our people practice these principles in various places of the world, incrementally better than each other. We keep ratcheting each other up. Every once in a while we discover the folks in Malaysia are doing something way better than the folks in Scotland, or the Scottish people teach our people in Austin, or vice versa. So the globality is of no moment, in terms of the objectives, or the standards, except that we find that some cultures adapt quicker, and then we all have to race to catch up to those cultures.

Aspray:

But what about distribution of design, or distribution of manufacturing?

Galvin:

It is pretty much all the same. For example, we have a manufacturing-research organization — I don't know if I'm using the right words here; it's a laboratory for manufacturing in two or three main places in the corporation. In every design organization, they're always designing for manufacturing. So we are teaching each other even from project to project. Whatever we discover is the best process, we'll put that into our Japanese plant, or we'll bring it from there and put it into our Phoenix plant, or put it into our East Kilbride plant.

Our orientation from this point forward is primarily to put factories somewhere else to serve markets. We are not putting them out for the sake of being the only or best answer to low-cost production. We are making a large number of our products now in towns near Chicago or in main towns in Florida, and shipping them all over the world. One of the great benefits of being in global markets is to be exposed to customers in parts of the world who may have different and better standards than customers at home.

Many of us have learned from the standards of Japanese customers. We decided a decade or more ago that we would find a way of totally satisfying Japanese customers, and believed that if we could do that, we could satisfy any customer in the world. Today we're finding some other customers are also very demanding, so we learn how to serve them. Then we can serve anybody else's customers. That's one of the great benefits of having a diversity of customers, finding the toughest customer and electing that person to be the one you are going to satisfy. Then you make everything else easier.

Japanese Competitors

Aspray:

I understand that, especially in the mid-'eighties, there was some concern about your Japanese competitors dumping and such. Can you describe the issue there?

Galvin:

Yes. That issue is really very simple. Among the strategic factors in business — and one that is insufficiently appreciated by a lot of people — is that there are people who would attempt to practice the principle of sanctuary. The Japanese practiced it and continue to practice it. Before, very substantially. Today, partially. They try to keep their home market a sanctuary. They build their strengths in the sanctuary, like a military organization would do. Then from the strength of your sanctuary, you can go out and do mischief, which is some kind of aggressive, competitive phenomenon. Dumping could be one of those things. Then when they have finally done enough harm to their competitor in the new market, they can take their strengths and build up the Japanese strength in the new market.

The Japanese recognize this. It's been a practice in the military for hundreds of years. And they practice it in business. So have some other countries. We recognize that and essentially said, "That cannot be tolerated because if they stay strong there, they will finally weaken us here, and we would finally go out of business." So we recognized that we had to break down that barrier. It was life or death. In military terms, you would have to attack the sanctuary of your enemy. We used every legitimate process that we could, starting with "let's be sure we have the right product, on time, the right quality, so that if they ever do give us an order, our product will satisfy them from an operational standpoint."

Then we did all kinds of things to make sure that we gained access to their market, the opportunity to quote and be received with some objectivity. To do that, we had to use wherever legitimate governmental tactics were at our disposal, such as saying: "You can't bring that mischievously priced product from your sanctuary into ours and do harm. You're dumping, and we won't let you do that." We used that and many other tactics to open up the market. We used our government, which is, in our estimation, a very legitimate thing. People can call it "protectionism" if they want; it isn't. They can call it "managed trade" if they want, and maybe it is. But you've got to manage not to let your opponent have a sanctuary. So we were very aggressive in that regard. We were the leading institution in the electronics industry. We opened the electronics market in Japan.

As a consequence, it's been very rewarding to us. Except for in what was honest-to-goodness recession in Japan last year, we kept our share up, and it was very hard to compete and make a profit last year by anybody in Japan. The Japanese lost a lot of money themselves serving themselves. But we're there. They know that we're going to stay there, and we're going to grow there. Therefore, they don't have a sanctuary any more. That's how you achieve a level playing field, by making sure the other fellow doesn't have a sanctuary, and you can be there.

Role of Government

Aspray:

Do you want to say any more at a philosophical level about the role of government in preparing an even playing field?

Galvin:

First off, I think the private sector can and should do virtually everything for itself. But there are things having to do with policy, such as we've just alluded to, that need government attention; and I won't repeat any interpretation of that. There are a few recipes in technology that look like they do have to have some degree of governmental support. I'll start with something as esoteric as the fundamental understandings of the essence of nature — the supercollider for example. To me the supercollider and the Fermi Lab, et cetera, are very relevant to today's engineers. A lot of people don't want to accept that because you won't know how to peel back that subatomic structure until the year 2009, so why don't we wait?

Well, we won't get it by 2009 if we don't spend now. So we need governmental support for things of a fundamental scientific nature. We need the National Science Foundation to support the research base of our country, which is the universities. That wouldn't get done if there wasn't a facilitating agent, and there is no facilitating agent except the United States government, mainly the National Science Foundation but also a couple of others. We have the government labs, as a coincidence because of our atomic energy program, for defense purposes. As long as they exist, they're a marvelous facility that can be converted and are being converted to handling major increments of advanced research projects. I'm the chairman of Sematech, and I see where the collaborative activities of both the private-sector and the complementary support from DOD have made a gigantic difference in that section of the semiconductor industry that makes the tools or the equipment. It looks like there is lots more science to be understood in semiconductors, so there is a place, I think, for the continuation of that joint research, although we may change the focus of one project versus another over the next five or ten years.

So I think there's a place for the government to do that. I think it's minimal in the sense that it will always be a minority of what the people will be doing. But I think we can find big slices of research that are of a fundamental nature, which if we can as a society know those principles very well, then all of the Intels and the Texas Instruments and the Hewlett-Packards can go and do a great job of taking that scientific basic knowledge and converting it into technology and useful applied things. So there's a role for government support of fundamental research. I wouldn't want to see any company subsidized, but I think we can identify potentially winning — and here we are going to be selecting winning and losing ideas — ideas that look like they are worthy of pursuit. We can follow them through to the point of showing they aren't any good, which is also valuable knowledge, or finish them out and be able to transfer that science to the appliers. So I think there's a role for government.

Capital Investment

Aspray:

Two last questions. The first is about investment in tools and equipment. In the semiconductor business, every time you go down a factor of ten in scale of device, your costs shoot up a factor of a thousand, or something like that. How do you face this in the future?

Galvin:

You face it by earning enough today to be able to afford it tomorrow. You can't earn enough today if you haven't anticipated and committed to the products that you can have early to market and earn enough on. Therefore, the cycle is a circle. We've been wringing our hands over this for forty years. I can remember in the 'fifties admonishing the guy that was running our semiconductor business: "Can't you learn how to run the semiconductor business with less physical capital?" A perfectly reasonable philosophical question to ask. But in the final analysis it was a naive question, and it had to be reshaped as: "how can we use the capital we're going to get more effectively? Because it's going to cost a lot of money to cook these silicon cookies." So we have just accepted the fact that it's going to be a very high physical capital cost.

When we have to buy a Stepper or something else, we want to figure out with quality systems how to get incrementally more out of our investment. If we can do that, and if the world is going to need whatever these circuits are going to be designed for, then we can compete. We'll make enough on that and be able to depreciate them enough. You will have to have some reasonable federal policies with regard to depreciation and allow abilities to earn some money, not be too heavily taxed on it — so that you can afford it. As far as we're concerned, we're going to be able to afford the next wafer-processing plant. When it goes to the next level of investment, we'll figure out a way to afford it.

Aspray:

I'm really very surprised by that answer. I had half expected to hear you say that it would be through collaboration with other organizations, through consortia and such.

Galvin:

I thank you for adding that. I guess I would have hoped that I would have said that more clearly when I spoke briefly about the government involvement. But not in terms of financing our capital structure. No, I don't see that. If indeed there is a science need that needs to be clarified or created, that I think is going to benefit from — and we should even be obliged to use — some consortia or government support to reach new possibilities. But once the science is adequately understood, then hopefully the general policies of allowability for depreciation, tax policies, et cetera, will let the private sector price and profit adequately to put enough on the bones to where we can afford the next option. Motorola and Intel and TI are all going to have to be able to afford most of these things themselves.

Now, are there exceptions? Sure. We'll sometimes join others. We've got a small joint effort with Toshiba. It's a big thing in some people's minds, but comparatively it's small. TI has got a new plant they went into in Singapore with a couple of companies. You'll have little pockets of these kinds of activities. But in the final analysis, if TI were to have three projects with three teammates, that means they have the equivalent of one big project. So they've got to afford some very big capital investments, and so do we. So does Intel, so does Hewlett-Packard, so does IBM, and all the computer guys, and so on.

Relationship of Military to Industry

Aspray:

The final question is about the military and its relationship to industry. The military has been so closely tied to high technology development since World War II. I know your company has jointly developed a chip with the Department of Defense, and that a small but significant part of your business is in the military area. Has this military-industrial relationship been beneficial over the past few decades? And how do you see it changing?

Galvin:

It has been beneficial, not in the direct transferability of one circuit over from the military to the consumer or commercial marketplace. But there has been considerable relevance. And, yes, we have been a part of military programs. We are absolutely a part of the Sematech. DOD-DARPA support things there. What we have done is to put limits on the nature of the things that we would offer as a service to the government. We never elected to go into the making of a missile, for example. But if there were missiles that were going to use some very new technologies, we will become a supplier of that subpart. We've found that that was a place we had value to add and a place where we could generate byproduct competencies.

You see, probably the grandest manifestation of this commercial payoff of military work was that our people had to become very proficient at understanding how to communicate through satellites. That derived for a few of our people a concept of a cellular telephone system with low earth orbital satellites as the waystations. But there's a derived competence to Motorola. Our people were able to extrapolate this idea from the projects we had. We've had a moderate number of things of that nature that have come along. That particular one, iridium, will be spectacular.

Now, what is the future? We think that our government — probably in your lifetime — is going to have to have a very extensive technology arms policy. A policy of having advanced technology applied to the armament needs of the defense entity. If we can maintain a competence, we will get a slice of that business. We will get the off-load or an off-benefit experience as well. So we intend to stay in that business. We think it's an honorable thing to support our government if they need armaments in that technology capacity. And we will get some secondary benefits from it. But we don't depend on it. I would say that would be a five to ten percent factor of our business. The size of the defense business has always been less than ten percent in our company. But it's another one of these great mountains to be climbing. If we can serve that market, we probably can transfer some competence over elsewhere.

- People and organizations

- Corporations

- Profession

- Business

- International collaboration

- Computer industry

- Quality management

- Research and development management

- Computing and electronics

- Semiconductor devices

- Electronic components

- Engineering and society

- International affairs & development

- Materials

- Semiconductor materials

- Engineering education

- News