Nanotechnology

There’s a lot of buzz—nanotechnology is “coming soon.” But what is nanotechnology? Why doesn’t anyone ever explain that? Well, it’s not that easy. While experts agree about the size of nanotechnology—that it’s smaller than a nanometer (that’s one billionth of a meter) they disagree about what should be called nanotechnology and what should not. Looking back at the historical roots of nanotechnology helps us get a better grasp on what nanotechnology is and why it’s important now, and how it will change the world in the future.

The story of nanotechnology begins in the 1950s and 1960s, when most engineers were thinking big, not small. This was the era of big cars, big atomic bombs, big jets, and big plans for sending people into outer space. Huge skyscrapers, like the World Trade Center, (completed in 1970) were built in the major cities of the world. The world’s largest oil tankers, cruise ships, bridges, interstate highways, and electric power plants are all products of this era. Other researchers, however, focused on making things small. In the 1950s and 1960s the electronics industry began its ongoing love affair with making things smaller. The invention of the transistor in 1947 and the first integrated circuit (IC) in 1959 launched an era of electronics miniaturization. Somewhat ironically, it was these small devices that made large devices, like spaceships, possible. For the next few decades, as computing application and demand grew, transistors and ICs shrank, so that by the 1980s engineers already predicted a limit to this miniaturization and began looking for an entirely new approach.

As electronics engineers focused on making things smaller, engineers and scientists from an array of other fields turned their focus to small things—atoms and molecules. After successfully splitting the atom in the years before World War II, physicists struggled to understand more about the particles from which atoms are made, and the forces that bind them together. At the same time, chemists worked to combine atoms into new kinds of molecules, and had great success converting the complex molecules of petroleum into all sorts of useful plastics. Meanwhile geneticists discovered that genetic information is stored in our cells on long, complex molecules called DNA (about 2 meters of DNA is packed into each cell!) This and other work led to a greater understanding of molecules, which, by the 1980s, suggested entirely new lines of engineering research.

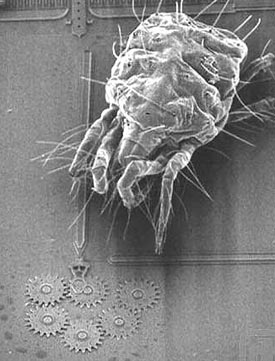

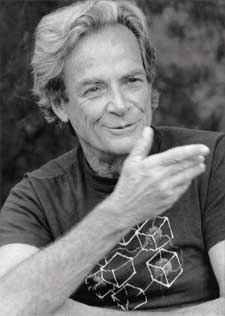

So, the roots of nanotechnology lie in the merging of three lines of thinking—atomic physics, chemistry, and electronics. Only in the 1980s did this new field of study get a name—nanotechnology. This new name was popularized by physicist K. Eric Drexler, who pointed out that nanotechnology had been predicted much earlier, in an almost-forgotten 1959 lecture by Nobel Laureate Richard Feynman, who proposed the idea of building machines and mechanical devices out of individual atoms. The resulting machines would actually be artificial molecules, built atom by atom. While the resulting molecule might itself be larger than a nanometer, it was the idea of manipulating things at the atomic level that was the essence of nanotechnology. But not only was this kind of manipulation impossible at the time, but few people had any idea why it would be useful to do it! With all the new research, however, Drexler revived Feynman’s vision and helped introduce the general public to the basic concepts of nanotechnology.

Although nanotechnology dates from the 1950s, the biggest changes have occurred just in the past few years. In the late 1990s, research money began pouring in from corporate and government sources. In the space of just a few years governments around the world launched three major (and many other smaller) new research programs, including the National Nanotechnology Initiative in the U.S. and the nanotechnology branch of the European Research Area. Japan has its own huge nanotechnology program, with money coming from private industry and government agencies such as the Ministry of Trade and Industry.