Petroleum Transportation Tanks

The original version of this article was created by Francesco Gerali, 2019 Elizabeth & Emerson Pugh Scholar in Residence at the IEEE History Center

It is recommended this article be cited as:

F. Gerali (2019). Petroleum Transportation Tanks, Engineering and Technology History Wiki. [Online] Available: https://ethw.org/Petroleum_Transportation_Tanks

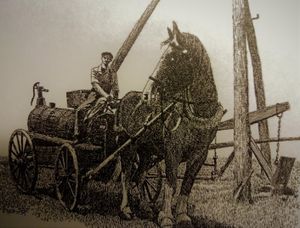

In Ontario at the beginning of the modern Canadian petroleum industry (1858-1860) when the quantities of petroleum produced were still relatively modest, a horse-drawn wooden tank wagon specifically designed for petroleum transportation was produced. These carts were primarily used to collect petroleum from the various wells and deliver it to the large petroleum gathering stations. The tank-cart could transport a volume of petroleum equal to several barrels in a safer way and substantially reduced the loading and unloading times. However, because of its size limits from the physical limitations of horse-power, the payload could not exceed a given threshold, and their service remained limited to short-range connection of small cargo.

The great increase of production of petroleum in 1860-61 generated a volume of mineral that was economically inconvenient for ground transportation via barrels and tank carts on wheels. In areas where waterways and barges were not available, railways offered an efficient and economical solution to transport petroleum to refineries and large population centers, and between 1861 and 1865, they became the primary ground transportation system. The horse-drawn wooden tank wagon, however, did not disappear completely from the transportation market. They were still very practical to distribute refined products in isolated rural communities. In Australia until 1920, there were regular distribution services for gasoline and kerosene from the depots in the main port towns such as Sydney and Melbourne, to the numerous farms and stations in the hinterland. They worked like mobile gas stations and were pivotal in fueling the remote rural and mining communities until the development of rails, roads, and pipelines.

Pipelining was evolving, but they held a secondary role in the U.S., Canada and Russia until the 20th century, and saw limited use in pre-World War II continental Europe. At first, adapted rail cars carried barrels racked up in special frames built over flat cars, and at the same time, patents were issued of railcars mounting vats, but none were commercially successful in the railroad market.

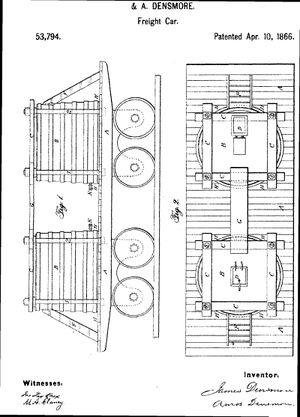

The New Yorker brothers Amos and James Densmore were the first to commercially produce rail tanks, marking the first massive turning point in the history of the petroleum logistics. Between 1863 and 1865 they engineered and tested their prototype of a rail tank car consisting of a pair of wooden tanks mounted on a flat tank. After much testing, on April 1866, they successfully patented their 3400-gallon tank car composed of two vertical positioned cylindrical vats (later a 3-vat longer version was also patented), made with wooden plates fastened by metal rings and with lids secured to a flatcar. These bore a close relationship to the twin containers used to haul iron ore and coal in the early days of the railroad, and this likeness showed a possible technology transfer, or at least influence in the design.

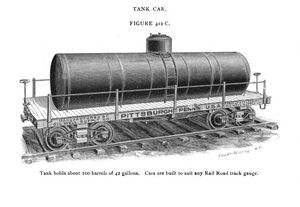

The Densmore design however was not free of issues. They were quite unstable, had a chronic problem of leaking, and optimizing the payload was impossible due to the given size of the flatcars. A few years later, close to the 1870s, the technical flaws of the Densmore design were overcome by the introduction of a riveted wrought iron, horizontal boiler-type, tank car. This new solution precluded leakages in transit, but did not overcome a serious safety issue when the petroleum was sloshed around in the open-topped tanks, because of the often uneven rail tracks built in the proximity of the petroleum fields. This and other issues related safety were soon addressed.

The unremitting increasing rate of petroleum production made the production of the rails tanks a very lucrative business. By 1888, there were approximately 6100 boilers (each capable of carrying 5000 to 6000 gallons) crossing the United States railroad system. Proven to be a great method of transporting petroleum and refined oils, in the 20th century the tank wagon was improved and adapted to haul the many chemicals resulting from the developing petrochemical industry.

See also

References

Beers, F. W. Atlas of the Oil Region of Pennsylvania. New York: F.W. Beers, A.D. Ellis and G.G. Soule, 1865.

Chernow, Ron. Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. New York: Random House, 1998.

Nelson, W.T. “Imperial Service”. The Imperial Oil Review 4, no 9 (1920): 17.

Oil Well Supply Co. Illustrated catalogue of the Oil Well Supply Co., Pittsburgh, Pa., also Bradford, Oil City, Pa., and New York City, U.S.A. New York: E.P. Coby & Co., 1892.

Peckham, Stephen Farnum. Report on the production, technology, and uses of petroleum and its products. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1884.

Pees, Samuel T., Senges, Richard. “The Densmore Brothers and America's First Successful Railway Oil Tank Car, 1865”. Oil-Industry History 5, no. 1 (2004): 3-17.

White John, H. The American Railroad Freight Car. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press), 1993.