Oral-History:Lotfi Zadeh

About Lotfi Zadeh

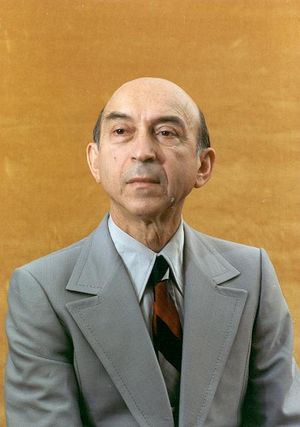

Lotfi Zadeh was born in Azerbaijan, the son of a correspondent for Iranian newspapers. After spending about ten years in the Soviet Union, Zadeh and his family returned to Iran. Zadeh received his bachelor’s in electrical engineering from the University of Tehran in 1942, coming over to the United States to continue his education in 1944. He received a master’s from MIT in 1946 and a doctorate from Columbia in 1949, both in electrical engineering. Zadeh also taught at Columbia, becoming an assistant professor in 1950 and associate professor in 1953 before taking a position at the University of California, Berkeley in 1959. He became Professor Emeritus at Berkeley in 1991, the year of this interview. Apart from teaching, Zadeh was involved in theoretical aspects of engineering with early work in systems analysis, but also developing theories of unvarying networks, sampled-data systems, an extension of Norbert Wiener’s theory of prediction, theory of the hierarchy of nonlinear systems, and z-transformation. Publications in the 1960s and 70s made famous Zadeh’s work on fuzzy sets and control, areas which he continued to work on as of this interview.

This interview discusses Zadeh’s career and theories, but often within the context of support given by the National Science Foundation (NSF) as research for a book being co-written by the interviewer Andrew Goldstein about the foundation’s promotion of computer science. Zadeh talks about the development of his many theories and the difference between theory and application. The application process for the NSF is also covered, along with Zadeh’s thoughts about peer review systems and the importance of reputation. The issue of fuzzy sets and logic is also discussed with Zadeh talking about the skepticism in the United States about fuzzy logic and non-quantitative thought.

About the Interview

LOTFI ZADEH: An Interview Conducted by Andrew Goldstein, IEEE History Center, 24 July 1991

Interview #112 for the IEEE History Center, The Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers, Inc.

Copyright Statement

This manuscript is being made available for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the IEEE History Center. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of IEEE History Center.

Request for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the IEEE History Center Oral History Program, IEEE History Center, 445 Hoes Lane, Piscataway, NJ 08854 USA or ieee-history@ieee.org. It should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user.

It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows:

Dr. Lotfi Zadeh, an oral history conducted in 1991 by Andrew Goldstein, IEEE History Center, Piscataway, NJ, USA.

Interview

Interview: Dr. Lotfi Zadeh

Interviewer: Andrew Goldstein

Date: 24 July 1991

Location: Telephone Interview

Education and Teaching

Goldstein:

Let me describe the project just a little bit. The book that we’re working on is a history of the National Science Foundation’s role in promoting and developing computer science in the past 40 years, and this particular chapter is going to describe some of the research that the NSF supported.

Zadeh:

Right.

Goldstein:

We went through a lot of the grants. We have lists of all the grants that were awarded, and picked out some key researchers, and identified the grant, the support they received, and now we want to try to describe in some detail the research that was done under those grants.

Zadeh:

Right.

Goldstein:

So I’d like to talk about some of the work you did with NSF support.

Zadeh:

Right.

Goldstein:

But I’d like to start by just getting some biographical information, if you could tell me about your education, and your—

Zadeh:

Okay. I received my bachelor’s degree from the University of Tehran.

Goldstein:

Yes.

Zadeh:

Okay. And that’s in Iran.

Goldstein:

Right.

Zadeh:

That was in electrical engineering in 1942.

Goldstein:

Yes.

Zadeh:

Let me mention that I received my high school diploma from an American college. It was called American College.

Goldstein:

In Tehran?

Zadeh:

In Tehran, yes. It was run by American missionaries, so it was called American College, 1938. And then BS degree in electrical engineering, 1942. Then I came to the United States in 1944 to continue my education. And I received a master’s degree from MIT in 1946 in electrical engineering. And then I moved on to Columbia University, and I received my PhD degree from Columbia University in electrical engineering in 1949.

Goldstein:

And then where did you go?

Zadeh:

Then I stayed at Columbia University. At Columbia University I was an instructor. From 1946 on, I was an instructor. And then in 1950, I became an assistant professor, and in 1953 I became an associate professor.

Goldstein:

All right.

Zadeh:

So, and then I came to UC Berkeley in 1959.

Goldstein:

All right.

NSF Support and Systems Analysis

And according to our records you were receiving NSF support as early as 1959. Can you recall the first date that—

Zadeh:

Well, I know that, that I was receiving it at Columbia University—

Goldstein:

Ah.

Zadeh:

I know that I started receiving support from National Science Foundation not that long after it was formed, because I do recall that the budget of the foundation at that time was about $15 million.

Goldstein:

Can you tell me something about the work that you were doing, right at the beginning?

Zadeh:

Oh yes, my early work was concerned with systems analysis. You see, what I have to do, really, [is] to look at the papers that I wrote at that time and check and see what sort of grants are credited [Unintelligible Phrase].

Goldstein:

Okay.

Zadeh:

I don’t have some of the early papers here, but the one that I can find is dated 1961.

Goldstein:

Yes.

Zadeh:

And it is credited to National Science Foundation. National Science Foundation, under grant G9106.

Goldstein:

You say that you were doing systems analysis, and I’m not sure that I understand what you mean by that.

Zadeh:

Well analysis of circuits and systems. My PhD thesis, which got quite a bit of recognition actually, that PhD thesis was published in 1949. And that was concerned with [Unintelligible Phrase] varying networks.

Goldstein:

Okay.

Zadeh:

I continued to do that. I think National Science Foundation was established in 1950, if I’m not mistaken?

Goldstein:

I think that’s right.

Zadeh:

Well, and then in 1952, ’53, ’54, and so forth, I was doing work on the analysis of circuits and systems.

Goldstein:

Was it general work in analysis, or particular circuits and systems you were looking at?

Zadeh:

General, general work. Now some of the papers that I have written during that time period have received wide recognition, where it was frequently cited in the literature, and so forth. So that when I wrote my first paper in 1965, it says I had an established position. In other words, I was not an unknown person.

Contributions, Sampled-Data Systems

Goldstein:

Right. Can you recall some of the notable results?

Zadeh:

I could fax to you something that summarizes some of my main contributions.

Goldstein:

That would be very helpful.

Zadeh:

If you’ll give me a second, I’ll do that, because that’s a little bit more detailed. I can send it to you, but we can continue our discussion right now. Well, let me tell you what I consider to be my most important contributions.

Goldstein:

Yes.

Zadeh:

First, development of a theory of unvarying networks. That’s number one.

Goldstein:

Yes.

Zadeh:

Number two would be development of a theory of sampled-data systems.

Goldstein:

Okay.

Zadeh:

[Number] three is an extension of Wiener’s theory of prediction. Number four would be development of a theory of, or, development of the theory of the hierarchy of nonlinear systems.

Goldstein:

Okay.

Zadeh:

And so this would be some contributions before I started working on theory of [Unintelligible Phrase].

Goldstein:

What - could you repeat the second one, please?

Zadeh:

Before prediction? Well, I started with theory of sampled-data systems.

Goldstein:

Right.

Zadeh:

And perhaps we should add to that, and Z-transformation.

Goldstein:

Now when you say a theory of sampled-data systems, is that a mathematical theory, a probabilistic theory?

Zadeh:

Well, not probabilistic. There were no probabilistic elements in that theory.

Goldstein:

Could…

Zadeh:

But it was - these things have become sort of standard now, and a particular approach that was described in that paper has become sort of standard. Z-transformation. Transformation has become a standard part of the theory of sampled-data. What it means is that time is not continuous, but it’s discrete.

Goldstein:

So I understand that they’re sampling - I understand what it means to sample data, and have a sampling rate, and -

Zadeh:

Right.

Goldstein:

Digitalize analog signals in that way. So when you say that you have a theory of it, I’m not sure what did the theory describe?

Zadeh:

The theory had to do with the use of what was called Z-transforms. So that the analysis of systems like that could be conducted in, conducted like the frequency analysis of linear [Unintelligible Phrase] varying circuits.

Goldstein:

I was going to ask, is this like in circuit analysis when you convert from the frequency to the time domain?

Zadeh:

The same thing happens in sampled-data systems, so that even though these systems are not like fixed systems because sampling takes place. Nevertheless, one can develop a theory which is very similar to the theory of linear circuits.

Goldstein:

Was there any related work going on, or were you the first to develop such a theory?

Zadeh:

Well, it was an important, let’s say, contribution. It was not the sort of thing which had no precursors. It’s frequently referred to, but it was not something out of [the] blue sky.

Theory of Prediction, Hierarchy of Nonlinear Systems

Goldstein:

Okay. Now Wiener’s theory of prediction I’m completely unfamiliar with. And I know who Norbert Wiener is, and I know his general area of interest, but, could you tell me something about the theory of prediction?

Zadeh:

Okay. Wiener came out with this theory of prediction. It was published in a book in 1948. And so it was a theory of prediction, and in this paper that I mention, it was written jointly with professor John Ragazzini, that theory was extended. It was generalized significantly so that later on, this paper was referred to in many places, and it’s usually included in collections of papers that are considered to be significant contributions to that theory.

Goldstein:

But when you say a theory of prediction, prediction of what?

Zadeh:

Time series.

Goldstein:

Okay.

Zadeh:

Time series predictions.

Goldstein:

And then you said that you worked on the hierarchy of nonlinear systems.

Zadeh:

Right.

Goldstein:

And what were some of the notable consequences of that work, just, again, influential papers?

Zadeh:

Well, I have written a number of papers on this subject. But for some reason, perhaps because of where these papers were published they did not have as much impact. I think that what happens frequently is that the impact of a paper depends not only on what’s in the paper itself but also where it gets published. It just happened that when the papers appeared in places like Journal of [the] Franklin Institute, you know, or Journal for Applied Physics and places like that, that are not read widely by people who do that kind of work. So even though I think that the work was interesting and so forth, somehow it did not have as much impact in terms of the number of citations and so forth.

Goldstein:

What sort of application did you expect for it? Who did you think would be interested? Who failed to pick up on it?

Zadeh:

Well, you know, during that period we are talking about early fifties.

Goldstein:

Yes.

Zadeh:

Much of the work that was being done was supported by universities, but had some sort of a defense orientation. And so applications - I mean, these theories, Wiener’s theory and this particular theory and so forth, they were concerned with signal processing, with fire control, with trajectory estimation, these were the main applications really.

Goldstein:

Okay.

Zadeh:

That work was not supported by any of the military agencies. Nevertheless that was the orientation. Not just of those papers of mine, but many of the papers that appeared in the literature at that time.

Goldstein:

I see. Would you work on discrete component networks to accomplish these jobs, say trajectory analysis or fire control? Or would you work on a mathematical theory that would…

Zadeh:

The thought at that point was this. If [Unintelligible Phrase] do certain things with linear trajectories, linear filters, and things of this kind.

Goldstein:

Yes.

Zadeh:

Now, the question at that time was, can you do better with nonlinear filter, nonlinear trajectories. And so in those papers, in which I talked about nonlinear systems, it’s a concept of hierarchy of nonlinear systems that was introduced, the simplest member of that hierarchy being linear systems. Above that you have systems which are somewhat nonlinear, and then more nonlinear, more nonlinear, and so forth, and so essentially, then, you put your finger on a certain element of that hierarchy and said, well, I will look for a system within this class.

Goldstein:

I see. And in conducting this work did you work much with hardware?

Zadeh:

No, I didn’t. I didn’t in general. I never worked with hardware, and I’m interested in hardware questions, but I never really concerned myself with hardware insofar as my research was concerned at that time.

Fuzzy Systems

Goldstein:

Was this a prelude to your work with fuzzy sets? Or is this an entirely different line of research?

Zadeh:

Well, it was. Essentially it was preliminary in some sense. In other words, how you work on systems analysis, which is sort of general analysis on systems. I became convinced that the techniques that other people and I were using at that time were not really adequate.

Goldstein:

Yes.

Zadeh:

They’re not adequate for dealing with what I call humanistic systems, or biological systems. They were good enough, perhaps, for electromechanical systems.

Goldstein:

Well, it sounds like as long as your operation is funded by, and directed towards military applications that is adequate because you’re only concerned with these electromechanical systems.

Zadeh:

As I mentioned, my work was not really funded by [the] military. I mean I had some support, you know, from a part of joint services electronic program and some support from ARO and so forth, but my work was never classified. It was not directly related to military applications. But, you know, in, I say, in sort of - it was influenced, of course, by the tenor of the time. Remember, that was the height of [the] Cold War.

Goldstein:

Yes.

Zadeh:

So people, including myself, thought that the war, World War III is around the corner, and so forth, you know. It was a different, different period, I guess.

Goldstein:

That’s true. When did you begin to feel this dissatisfaction with the…

Zadeh:

I would say around 1960, ’61, I began to feel that conventional techniques that I was developing at that time, and other people as well at that time, were not really the right techniques.

Goldstein:

Yes.

Zadeh:

Dealing with these more complex systems.

Goldstein:

And what did you do? How does one set out to introduce a new approach to these things?

Zadeh:

Well, in a paper that I wrote in 1961, for example, which was supported by [the] National Science Foundation, I did mention at some point that the conventional techniques are not really adequate. What we need is something that can deal with fuzzy systems. So I was conscious of that, but it took me a while to come up with this simple idea. But, you know, sometimes something has to germinate.

Probabilistic and Discrete State Systems, NSF

Goldstein:

I’m wondering what research proposals you were submitting to the National Science Foundation between 1961 and 1965, in those years where your ideas were beginning to crystallize on the idea, what were you telling NSF you wanted to do?

Zadeh:

Well, at that time I was concerned to a very considerable extent with probabilistic systems, finite state machines and probabilistic systems, so I’d gotten away from the sort of things that I was doing in the middle fifties, or late fifties. I moved on to probabilistic systems and discrete state systems.

Goldstein:

This was highly theoretical work, I imagine.

Zadeh:

It was theoretical. I wouldn’t say it was highly theoretical. [Unintelligible Passage] theory is all.

Goldstein:

Well, was there any concrete application that you could see then or has resulted since?

Zadeh:

Well, basically, I think the attitude of many people, including myself at that point, was that we will develop the basic things and somebody else will make use of these results in the design of practical systems.

Goldstein:

Yes.

Zadeh:

without feeling in any sense that they had to go beyond that.

Goldstein:

Right.

Zadeh:

That was the tenor of the time.

Goldstein:

Okay. I see.

Zadeh:

So that was the situation. There was no pressure on me to come up with something, you know, that was very practical.

Goldstein:

Yes.

Zadeh:

The National Science Foundation at that time did not support work, you know, that was sort of oriented towards practical applications.

Goldstein:

Right. I understand that they were a valuable resource for people interested in pursuing theory. Is that one of the reasons why you turned to them for some support?

Zadeh:

Yes. That’s right. They’d say well, that’s too applied. That was the attitude at that time. And then there was a shift in some of these attitudes, but that came later, much later.

Goldstein:

Okay. How were your relations with the foundation? Were they interested in the research that you were suggesting? Did they have any suggestions themselves or try to steer you in any way?

Zadeh:

No, they never did. The National Science Foundation, and this is something that I personally have certain views about, has never taken an activist position, never tried to encourage or discourage something. They’re sort of - and I have been somewhat critical of that, critical of a sort of a stance which involves waiting until someone submits a proposal, then you either approve it or disapprove it. But they don’t start any kind of initiative. It’s in more recent years the foundation has become somewhat more activist. But at that time it was considered to be in poor taste, of tell[ing] the investigator to do this or not to do that, and so forth.

Goldstein:

I see.

Zadeh:

The investigator was supposed to be free from pressures of that kind.

Goldstein:

Were they your sole source of support at that time?

Zadeh:

No, I was receiving support from the National Science Foundation. I also received support from NASA. But the NSF was my main source of support.

Results from NSF Years, Proposal Writing

Goldstein:

I’m wondering what some of the most productive results from those years [were].

Zadeh:

I’ll tell you one thing, that in the case of fuzzy logic - now it’s really easy to point to all kinds of applications and say well, these applications followed from this basic research.

Goldstein:

Right.

Zadeh:

But it’s much more difficult to do that in the case of the kind of research that I was doing, and other people were doing at that time, because most applications were not in the commercial realm. They were in the military realm. Most of the applications were classified. So that once in a while one would become aware of the fact that some of these ideas were employed in some military systems, radar systems, and so forth. In most cases, you really didn’t know where those ideas were applied.

Goldstein:

I see. Then did you - starting in the mid-sixties when you began to work, am I correct when I say that’s the time when you began to work on…?

Zadeh:

[Interposing] [Unintelligible Phrase] was the publication date of my first paper on fuzzy sets.

Goldstein:

And how did your - what were your proposals to the foundation like then? How were you describing your work to them?

Zadeh:

Well, I was working at that time to develop this theory of fuzzy sets, of classes which do not have sharply defined boundaries. And so ’65 represents a turning point in my career in the sense that I from that point on I was working only on fuzzy sets.

Goldstein:

In writing your proposal, were you obliged to describe why you think the work was important?

Zadeh:

Yes, my justification was that conventional techniques are much too precise for the pervasive imprecision of the real world. That somehow we were on the wrong track in trying to attack all these very complex imprecise [Unintelligible Phrase] through the use of very precise techniques. There was a mismatch.

Fuzzy Sets, Control and Linguistic Variables

Goldstein:

And could you just tell me the story of these early investigations into fuzzy sets?

Zadeh:

Fields like psychology, philosophy, perhaps medicine, and fields in which you deal with very complex systems which are not electromechanical systems. So that was essentially my orientation. But then after a while I began to see that these techniques could be employed successfully also in the design of conventional electromechanical systems. It was in 1972 that I wrote my first paper called “The Rationale for Fuzzy Control.”

Goldstein:

Right.

Zadeh:

Today, most of the applications are in that realm, in the realm of fuzzy control.

Goldstein:

How did you imagine the concept of the fuzzy set being applied in these humanistic systems? Did you expect that a human agent would assign the varying probability weights to the different elements, and…?

Zadeh:

Here was the basic idea. I think this turned out to be the key idea, that in the [Unintelligible Phrase] of fuzzy sets and fuzzy logic you introduce the concept of what’s called linguistic variable. The values of a linguistic variable are words rather than numbers. so the point that was made in these early papers of mine is that when we communicate with one another, we frequently use words like this - Mary is tall, or young, or not very intelligent, or something. You don’t put a number. You don’t say her IQ is 173. You don’t say that she is five-ten. Although you could in principle. But you use words most of the time.

Goldstein:

Right.

Zadeh:

And so the theory of fuzzy sets, then, provided a framework for dealing with variables whose values are words and which would then make it possible to deal with situations which don’t lend themselves to analysis in terms of numbers. And so that was the basic idea. So that, since no such theory was available at that time, I thought that it might be useful in dealing with these humanistic systems.

Goldstein:

But I would imagine that you’d still need some sort of calculus with which to compute based on these linguistic variables.

Zadeh:

That’s right. Underneath these words, there are numbers, but they’re underneath, so they’re not very visible.

Goldstein:

Right.

Zadeh:

So you manipulate. You can multiply small by large. You see, you can do these things.

Goldstein:

I’m just wondering then did you consider the implementation of these procedures? Were they supposed to be done on computers?

Zadeh:

Again, I did not concern myself with implementation.

Goldstein:

Okay.

Zadeh:

My assumption was that some other people would do that.

Goldstein:

Right.

Zadeh:

So that was my expectation. But then it turned out that these techniques, techniques involving the use of so-called linguistic variables, turned out to be pretty useful also in dealing with electromechanical systems. But there it’s not that we cannot deal with these electromechanical systems using just conventional techniques, but it turns out the use of words simplifies their design.

Goldstein:

And could you describe how?

Zadeh:

Yes, well, let’s take the example of parking. Suppose somebody told you ‘design for me a system that would park a car automatically,’ okay? You work for some automobile company, and they tell you to do that. Now if you try to come up with a program which would do it numerically, [you] would find it very difficult to do so.

Goldstein:

Right.

Zadeh:

But if somebody says describe it in words, you could do it. You see? If somebody asked you, ‘how do you park a car,’ you would simply describe it in words not in terms of numbers. You would say, well, take your car and put it, you know, close to the car in front, or within a few feet, or something. You would be using labels like that.

Goldstein:

Right.

Zadeh:

Rather than so many inches, and turn by 5 degrees, and so forth. It turns out that if you allow yourself the use of these linguistic variables, then you can design a system much more simply.

Goldstein:

Right. Although there has to be some mechanism for translating the linguistic quantity to mechanical action. I mean, in the case of just telling someone how to park a car people’s judgments come into effect.

Zadeh:

Well, you have to calibrate these things. But it turned out that this calibration is relatively simple. It’s difficult to describe to you over the telephone, but it turned out that there is such a thing as the theory of these linguistic variables. It involves calibration, which involves arithmetic operations, which involves all kinds of things. But it turned out that that approach provided the key to the solution of many of these problems.

Citation Classics, Application Questions

Goldstein:

What were the, the elements of the papers that you published on this subject?

Zadeh:

Well I’ve written quite a few papers. Now some of these papers - there were two papers that were citation classics. You know, there’s a citation index.

Goldstein:

Right.

Zadeh:

And my first paper on fuzzy sets, that was a citation classic. Then a paper that I wrote in 1973, in which I just introduced this concept of linguistic variable was also a citation classic. And now, the total number of papers dealing with fuzzy sets and applications at this point, might be around five, or six thousand, something like that.

Goldstein:

Right. [Laughter]

Zadeh:

So the literature is very substantial at this point.

Goldstein:

Now, would people contact you who did have specific applications in mind? For instance, I know the whole idea is used extensively - or it’s trying to be applied to industrial robots. Would certain groups approach you and ask for consultation services or particular attention to a given problem?

Zadeh:

Sometimes they do. I’ve never been heavily involved in consulting and so forth, as some people are. But I frequently get calls. I get two or three calls in the course of a day, questions relating to fuzzy logic applications or requests for information. And I do have some association with companies, corporations and so forth.

Goldstein:

Mm-hmm.

Zadeh:

And so, yes, people do call me. They ask me - sometimes I refer them to some other people, who could spend more time with them.

Goldstein:

Right.

Fuzzy Logic in US and NSF, Peer Review

Zadeh:

Depending how the applications can be made. What has happened is that during the past year in particular there has been a resurgence of interest in fuzzy logic in the United States.

Goldstein:

Mm-hmm.

Zadeh:

In the United States there has been quite a bit of skepticism with regards to fuzzy logic and its applications, so that there was a lot of pooh-poohing going on, and the National Science Foundation, and many of the other funding agencies had been influenced by that, in the sense that many people working on fuzzy logic did not even bother to submit proposals to [the] National Science Foundation, because they knew that they would be sent to review, which would be very hostile.

Goldstein:

Yes.

Zadeh:

There is a point that I should like to make, because I think it’s an important point. My work on fuzzy logic was supported by the National Science Foundation, I think, largely because of my earlier work, which preceded fuzzy logic.

Goldstein:

But you’d established a reputation. You were able to keep a positive image.

Zadeh:

[Interposing] [Unintelligible Phrase] and I would submit a proposal having to do with fuzzy logic, it would be funded, but it would be in spite of my work on fuzzy, and not because of it.

Goldstein:

Well now that’s interesting. What gives you that impression? Was it the comments by the peer reviewers, or your discussions with program officers at NSF?

Zadeh:

Yeah. That’s right. And also the fact that people, other people submitted proposals also related to fuzzy logic, had the proposals turned down. Since I had the close association with NSF, I had an established track record, and so forth, I would submit a proposal, and it would be funded.

Goldstein:

So you feel that the investigator - that perhaps the investigator more than the research topic…

Zadeh:

Exactly.

Goldstein:

Was-

Zadeh:

- Audio File

- MP3 Audio

(112 - zadeh - clip 1.mp3)

I think that this is the very important point. I think a very important point, because I think it has to do with how the peer review system functions, you see. And so what happens then is that it’s very much a matter of what your reputation is, and it’s a little bit the way it is in the field of art. I don’t know if you have heard about the experiments, whether it would take the painting of somebody famous, put some unknown name there, and put a ridiculous price, let’s say $18, you see. But if it were a famous painting, then it would bring $1 million.

Goldstein:

Right.

Zadeh:

And so the problem is this. You submit a proposal, and you find that if you are Professor X, you know, who has a reputation, and so forth, he’s an influential person then the probability that a proposal will be funded is much, much higher than when the same thing is submitted by some unknown person.

Goldstein:

I see.

Zadeh:

And so what happens is that in the case of something that’s controversial, like fuzzy logic’s been, the peer review system does not function well, because what happens then, proposals sent to people who are - don’t know what fuzzy logic is, or are hostile to fuzzy logic for one reason or another, and so people, many people have been sending comments over these years, to me. In other words, they would have the proposal turned down. They would send me the comments, so I have a collection of these things. For example, something saying that it has been proved that fuzzy logic has no practical application. I mean, the person doesn’t even know what fuzzy logic is. And these days, it is sufficient to have just one negative review, you know, to blackball the whole thing.

Goldstein:

Can you name any very interesting research proposals that weren’t funded because the PI was relatively unknown?

Zadeh:

Well, let me give you just one name. You can call him, and I think he might be interested to talk to you. You know, he was very much involved in these things. Dr. E., that’s his initial, Ruspini.

Goldstein:

Mm-hmm.

Zadeh:

Ruspini. He is with SRI International in Menlo Park.

Goldstein:

Right.

Zadeh:

Okay. Now, let’s see, he’s supported by contracts.

Goldstein:

Yes.

Zadeh:

In my case whether I get a grant or not, you know, is not that important, but he is a man who is supported by grants, so for him, having his proposal approved means much more. It’s much more important to him than it is to me. And so he has submitted a large number of proposals, but it’s only within the past two or three years that his proposals were funded. He has had [a] very, very hard time. Even though his work is very good, and he is known very - I mean he is well known within the fuzzy logic community, but not outside of the community. He collected all of these reviews and this and that, and so forth. He will tell you many true stories about what happens to people.

Goldstein:

I see. Can you think of any other research areas that perhaps didn’t get any support? You say that fuzzy logic got a boost because you’d made your reputation in a different area. Are you aware of any situations where…?

Zadeh:

I cannot think of any comparable situations. There are other situations which resemble it to some extent, such as neural networks, but I don’t think that’s something that really compares with fuzzy logic insofar as degree of hostility and skepticism is concerned.

Goldstein:

Now how do you account for the hostility and skepticism? Why do you think people have been reluctant to - ?

Zadeh:

There’s no single reason. But one of them has to do with the word “fuzzy.” It sort of turns off people, so immediately the attitude, okay, this must be a joke, until you can prove otherwise.

Goldstein:

Okay.

Zadeh:

But people overcome that sort of a thing, so beyond that it’s not simply that, but also because, you see, there is a very deep-seated tradition in Western cultures, which is the tradition of respect for what is quantitative, precise, rigorous, and so forth.

Goldstein:

Certainly.

Zadeh:

And I myself was steeped in that tradition. But then somebody comes along, says, you know we have to put that tradition aside. Let us use fuzzy logic, which is the logic of approximate reasoning, basically. That does not sit too well with many people. The use of words instead of numbers doesn’t sit too well, because people tend to become more and more quantitative. You see? That’s what economists do. That’s why some people get Nobel Prizes in economics, because they come up with quantitative theories, you know.

Goldstein:

Mm-hmm.

Zadeh:

So, there are many, many things of that kind. There are many traditions that push people in certain directions. So when somebody comes along, says, well, let’s abandon this approach, it doesn’t sit too well. Doesn’t sit too well. And so in the case of neural networks, for example, you’ll have some hostility, but it’s nothing like what you encounter in case of fuzzy logic, because neural networks is still more or less in sort of a traditional mold.

Goldstein:

Do you feel that this aspect of the Western culture explains why fuzzy logic has been embraced more warmly in Japan?

Zadeh:

Not to the extent of 100%. There’s [Unintelligible Passage] also. What I would say, perhaps, is the extent of 70% or 60%, something like that.

Goldstein:

Okay.

Zadeh:

But in those cultures there is less of this Cartesian tradition for respect for what is rigorous and precise and quantitative. That tradition is not as strong in those cultures. They are old cultures, and people in those cultures take it for granted this world is a very complex world. There are shades of gray. So it’s not a very - you can’t say it’s black and white, true/false. Let me put it this way, it doesn’t conflict with a tradition that we have in this country, and European countries. Younger cultures, Western cultures, tend to be like that.

Goldstein:

Right. I wonder if you reflected on your own ethnic heritage, do you think that it in some way left you free to see outside of this Western bias?

Zadeh:

Perhaps, but what was more influential in my thinking is that I’ve never never hesitated to go against something, or some tradition. I’m not the kind of person who is strongly influenced by what appears to be sort of dominant ways of thinking. I never hesitated to depart from that. And so this fuzzy logic is just one example of that sort of thing. There are many other things, both within my work, and also outside, where I said, well there’s no reason why we should necessarily proceed in this direction. And probably this attitude of mine, which is sort of a personal attitude, probably has been more influential than this cultural thing. But also, I was born in the Soviet Union, and although I was not a Soviet citizen, my father was a correspondent for the Iranian newspapers.

Goldstein:

Yes.

Zadeh:

So I was an Iranian citizen. I was born in the Soviet Union. I lived there until the age of 10. I went through the first three grades of elementary school, and I was exposed to all kinds of ideological indoctrination at that time, which was strongly anti-religious, you know, that sort of stuff.

Goldstein:

Right.

Zadeh:

And my parents take me to Iran, where I was put in an American missionary school. Where we had chapel every morning, you know. And then from that school I had to go to an Iranian school. We had religious fanaticism of this Muslim kind over there, and so forth. So having seen, having experienced these fanaticisms of one kind or another I’ve become tolerant. I become sort of convinced that it’s not necessarily the case, just because everybody around you thinks that something is right or something is wrong, that that is really the case.

[End of Tape 1, beginning of Tape 2]

Defending Fuzzy Logic, NSF Rapport

Goldstein:

Well, I'm going to try to pick up the conversation again.

Zadeh:

Let me mention a couple of things that, perhaps, might be of interest. At some point, I got close to getting the Golden Fleece Award. Senator Proxmire wrote a letter to the National Science Foundation and asked the Foundation, "Why are you supporting this nonsense on fuzzy logic, and fuzzy set theory, and so forth?" And so then I had to write and explain this and that.

Goldstein:

That's interesting. The Foundation didn't defend you themselves, they forwarded the accusation to you, and asked for your response?

Zadeh:

I can't remember whether they did it in writing, or whether they did it over the telephone. No, the Foundation has always been very supportive in situations of this kind. But of course, a letter of intent intimidates some people, you know? When Senator Proxmire gets into the act, and so forth. I had similar experiences with other agencies, where, for example, my work was supported by Naval Electronics Systems Command. The person who was supporting me was very much in favor of what I was doing, but people above him were questioning it. And so he was under pressure to terminate this work. You know, he didn't go along, but there were pressures exerted. They said, "This is a bunch of nonsense. Why are you supporting this kind of work?"

Goldstein:

Well, why do you suppose that the NSF didn't react? I don't know if they simply overcame the pressure, or if they themselves didn't feel any uncertainty about supporting your work? Why were they so sympathetic? You say it's because of your reputation?

Zadeh:

Well, partly. Of course, you know a reputation matters if the people really don't know you that well. But when you work with people, when you know the people, then what matters is their perception of you at close distance, rather than your reputation in the outside world. Now I always had a very good relationship with the program data director myself. So they were always very supportive of what I was doing.

Goldstein:

Who were some of those early program directors, with whom you had established a rapport?

Zadeh:

Let me try to think now. Let me try to think of some of the program directors. I think I have a little bit of difficulty at this point. A little bit of difficulty recollecting the names. This was some time ago. More recently, I remember, but going back nearly 20 to 25 years it becomes more difficult for me. But almost without exception, I had good relationships with program directors. They were very supportive. I want to repeat again, this was not based on reputation, but based on what they saw. I had a very good relationship with program directors within other agencies. And also with the Navy. But the people who were not that close, not that they were not supportive, but they simply sometimes would listen to people who were hostile.

Goldstein:

Right. So you felt that your relationship with them permitted them to keep an open mind, and consider the possible merits of the proposal?

Zadeh:

That's right. Just to give you an example, in the case of this Navy grant that I had, one day he called me and said to come to Washington. So, I went to Washington and together we went to see his superior. And his superior was very skeptical. Very, very skeptical. And he had a couple of others there. it was like an inquisition. "What is this? What is that?" It was very much like an inquisition. Well, I had been able to answer the questions, and so forth, so eventually they said, "Okay." But apparently, they were getting some input from other people within the scientific community that were saying, "This is a bunch of nonsense." And, so forth, you know?

Goldstein:

The people who were skeptical that way, did they have the scientific savvy to understand, to make legitimate criticisms, or did you have to answer in terms of applications or in more lay terms?

Zadeh:

Now, here's the situation. They were very intelligent, very knowledgeable people, but they didn't know anything about fuzzy logic. That's the position I can say categorically. It is very difficult to find a person who is very critical of fuzzy logic and at the same time knows something about fuzzy logic. They are very critical of something they are really not familiar with. In other words, they heard certain things, they had formed certain perceptions, and so forth. But, they didn't know really what it is.

Practical Applications of Fuzzy Logic

Goldstein:

Right. You said that in the early '70's there was this shift over from human systems to electro-mechanical systems. Were there any other major shifts in emphasis in your work?

Zadeh:

Well, back in 1972 I wrote a paper called, A Rationale for Fuzzy Control. That was the first thing that suggested that there might be some application for fuzzy control. And then the first practical demonstration of that was done in England, in a paper that got to be well known by Professor [E.H.] Mamdani and his affiliates in 1974. So from that point on, then, there were quite a few practical applications. The first industrial application was in cement fuel control in 1976 that was done in Denmark. And today, almost all cement kilns use fuzzy logic control.

Goldstein:

These are cement kilns, you're saying, like the ovens that cook?

Zadeh:

Right. Well, 1976 was the first time. Today we are in 1991. It took fifteen years for the technology to become changed. Essentially it took fifteen years.

Goldstein:

Right.

NSF Divisions and Research Monies

Did you have steady support from the National Science Foundation during this whole period?

Zadeh:

Yes.

Goldstein:

I see.

Zadeh:

Yes. I had steady support. I do not have NSF support at this point, but I don't have it because I have not submitted a proposal to continue some of my work.

Goldstein:

Did the director that you applied to, did that ever change, or was it always the same office, the same administrative branch?

Zadeh:

Well, my support came from two directors. One was the engineering director, and the other one was basically from information science, or at that time it was part of the director of biological behavior sciences. More recently became computer science.

Goldstein:

Well, that's interesting. It went from biological science to information sciences?

Zadeh:

Within that director of biological behavior of social sciences there was a division. It was called Division of Information Sciences Technology.

Goldstein:

[If] people were doing mathematical work, you know, Shannon style work, they'd be getting it from there?

Zadeh:

So, my support came from that division. And after the re-organization took place, and they established computer science as the directorate…

Goldstein:

That was in 1967?

Zadeh:

No, more recent than that.

Goldstein:

Oh, really. When?

Zadeh:

That was in, I would say about five, six, seven years ago.

Goldstein:

Okay.

Zadeh:

It was in the '80's. It was a re-organization. A reorganization of that division, and it was moved to a new director, computer science and engineering director. From that point on then, my support came from the computer science and engineering director.

Goldstein:

Okay. Did that subsume the engineering director?

Zadeh:

No, that's a separate thing. I had two separate sources of support.

Goldstein:

I understand. I'm interested when you said earlier that it's not that important if you don't get a grant. Is that because you're well taken care of in your laboratory?

Zadeh:

No, I didn't mean that. What I meant by that is, it's not a matter of life and death. In other words, my share of it comes from the university. The University of California is a state university, which means that my academic salary comes out of the state budget. It doesn't come out of research grants.

Goldstein:

Right.

Zadeh:

Sometimes institutions, in many cases, one-half of the professor's salary comes out of a research grant.

Goldstein:

That's the situation we have here, actually. We're a research institute.

Zadeh:

That's right. Now, at a place like SRI, 100 percent comes out of research grant[s]. But when I say it's not a matter of life or death, what I meant by that was, it's not a matter of losing my job.

Goldstein:

Right.

Zadeh:

It might mean, of course, I might not be able to travel, or I might not be able to hire a student, but it's not a life and death proposition.

Goldstein:

That's another question I wanted to get to. What were the budgets of your grants? You're saying that you didn't work with hardware.

Zadeh:

Some of them, they were $80,000, $100,000.

Goldstein:

And the money was to be spent on travel expenses, or staff time.

Zadeh:

Everything included. Everything included, from the National Science Foundation. It was on the order of $80,000.

Goldstein:

Could you identify some of the usual budget categories?

Zadeh:

The usual budget categories would be, for example, my academic salary during the summer, RA support. Support - this was a principal item.

Goldstein:

Did you work very closely with many grad students?

Zadeh:

Well, I never worked very closely with my grad students. I have a good relationship with them, for seminars, but I have never written papers with my grad students. My papers are written by myself. So, it's the kind of interaction where they come to see me, I tell them to do this, do this, and so forth. They come back in a few days time, and they show me what they've done, and then I make some further suggestions. It's not like that. Not that close, let's put it that way.

Goldstein:

Okay.

Natural Language Processing and Expert Systems

Goldstein:

When you examined the developments over in Europe, with practical applications of control, were you, during that time - your more theoretical work - were you still looking into questions of control, or had you developed something else?

Zadeh:

Well, I moved on to some other things. I moved onto other things. In general, the way I operate does not necessarily mean that I think that's the right way, it's simply, you know, the way I operate, whether it's good or bad. I take an idea, I develop it to a certain point, and then I go on to something else. In other words, I do not push it very far. I assume that other people then might be able to pick it up from that point on, and do a better job than I can in implementing the idea.

Goldstein:

So, after you moved on from fuzzy control, where did you go?

Zadeh:

Well, for example, I've been very much interested in natural language processing. Expert systems. And applications of fuzzy logic to expert systems, natural language processing…

Goldstein:

Now how does that work? I don't know that I have any sense of what the interaction could be.

Zadeh:

Well, in the case of expert systems, that's an important application area. Because in the case of expert systems, the knowledge that might be resident in the knowledge base frequently is uncertain, and so forth. The question is, how do you manipulate that kind of knowledge. That's where fuzzy logic comes into the picture. Fuzzy logic is better suited for dealing with knowledge like that, than classical logical systems are, in an application area. The other application area has to do with [Unintelligible Passage] it's not control, but qualitative systems analysis. They deal with systems, but the dependencies between variables that describe the linguistic terms. These are other areas that I've been interested in.

Goldstein:

In the case of natural language processing, is that a system interpretation of fuzzy logic?

Zadeh:

Primarily meaning representation. It's a proposition of language. How do you represent a meaning of that proposition? And that's where fuzzy logic comes into the picture.

Goldstein:

Okay. I guess I want to take a look at the pages you're going to send me, and try to integrate that with some of the material I've gotten here today.

Zadeh:

I'll send them to you, and I'll give them to my secretary, and I'll send them right away.

NSF's Role

Goldstein:

Okay. I'd like to give you an opportunity to highlight any particular portion of your career that you think deserves special attention, or offer any insight you have into your work, or the role of the National Science Foundation.

Zadeh:

I think I'd put it this way. First of all let me say, I think, in my case, the National Science Foundation played a very important role for my research. And I have no criticisms, no complaints, nothing. I mean, there have been these problems, as I mentioned, that many researchers have found it very difficult to get support. But that's because of some of these attitudes. And so, I have nothing but praise for the National Science Foundation. Okay, so I'm going to send you this thing.

Goldstein:

Okay. But what I'd like to do is take these materials and develop the small article that we intend to include in the book, and then perhaps send it to you, and you can review it for accuracy.

Zadeh:

Okay. That sounds fine. Thank you very much.

Goldstein:

Thank you for taking the time to talk to me. It's been very, very instructive.

Zadeh:

Thank you very much. Bye-bye.

Goldstein:

Good-bye.