Oral-History:Arthur D. Pelton

About Arthur D. Pelton

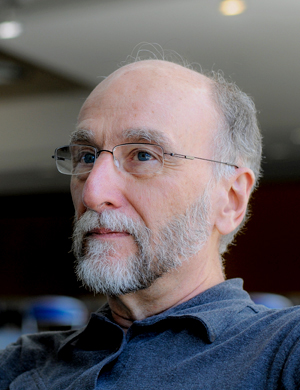

Arthur D. Pelton is Professor Emeritus in the Dep’t.of Chemical Engineering and co-director of the Center for Computational Thermochemistry at Polytechnique Montréal in Montreal, Canada. He is a co-founder of the FactSage thermodynamic database computing system.

Dr. Pelton received his undergraduate and graduate degrees from the Dep’t. of Metallurgy and Materials Science at the University of Toronto (PhD in 1970). Following post-doctoral studies at the Technical University in Clausthal, Germany, and at MIT, he joined the faculty of Polytechnique Montréal in the Dep’t. of Materials Engineering in 1973. Dr. Pelton has co-authored over 300 technical papers and is the author of a monograph on “Phase Diagrams and Thermodynamic Modelling of Solutions” (2018) as well as 16 book chapters. He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, the Canadian Academy of Engineering, and the American Society for Materials. He is a recipient of the AIME Extraction & Processing Distinguished Lecturer Award, the Gibbs Triangle Award of Calphad, the J. Willard Gibbs Phase Equilibria Award of ASM, the John F. Elliott Lectureship Award of AIST, the Arcelor Mittal Dofasco Award, and the Hume-Rothery Prize of the Institute of Materials (UK) as well as other national and international awards. His primary field of interest is chemical thermodynamics.

Further Reading

Access additional oral histories from members and award recipients of the AIME Member Societies here: AIME Oral Histories

About the Interview

Arthur D. Pelton: An Interview conducted by Tom Battle in 2018 in Ontario, Canada.

Copyright Statement

All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between the American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical, and Petroleum Engineers and Arthur D. Pelton, dated August 29, 2018. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical, and Petroleum Engineers. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical, and Petroleum Engineers.

Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical, and Petroleum Engineers, 12999 East Adam Aircraft Circle, Englewood, CO 80112, and should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user.

It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows:

Arthur D. Pelton, “Arthur Pelton: The 50 Year Journey Creating FactSage,” an oral history conducted by Tom Battle in 2018. AIME Oral History Program Series. American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical, and Petroleum Engineers, Denver, CO, 2019

Video

Transcript

INTERVIEWEE: Christopher Bale

INTERVIEWER: Tom Battle

DATE: 2018

PLACE: Ontario, Canada

PART 1

00:19 INTRODUCTION - FIRST RECOLLECTIONS ON USING FACT

Battle:

Good morning. This is Wednesday, August 29th, 2018. And we're in the Westin Hotel in Ottawa, Canada. My name is Tom Battle. I'm an extractive metallurgy consultant and TMS volunteer, and I'm here at Extraction 2018 with professors Arthur Pelton and Christopher Bale from the Ecole Polytechnique in Montreal. Welcome, gentlemen. I appreciate your taking the time to meet with us today and talk about your careers, particularly your work with the thermodynamic software package now called FactSage.

I can't help recalling the first time I used your package, which was known as FACT at that time in 1990. It was only available through a phone connection to the computers at McGill University, which wasn't always available. The software wasn't particularly user-friendly, and the results of the analyses rather cryptic. Certainly, you'd agree it's primitive by today's standards, but it strikes me now with all my grumbling and complaints at using your software at the time that, if I wanted to do the same slag metal equilibria calculations I was interested in then, but didn't have FACT available, what would I have done?

Pelton:

You would have taken out your hand calculator and spent a few days doing the calculations.

Battle:

Well, I would have had to find the thermo tables.

Bale:

You'd need the models as well, you know. Stated, it would be tough.

Pelton:

It would be difficult.

01:59 TEACHING - THE MOTIVATION TO LEARN THERMODYNAMICS

Battle:

Now, was this difficulty in doing these complicated calculations part of the research that led you to develop FACT in the first place?

Pelton:

Why did we develop FACT in the first place? Well, everything just sort of came together at the right time. Chris and I worked together at the University of Toronto. We were demonstrators in a laboratory of thermodynamics given by my professor, and that's where we taught each other thermodynamics because we had to teach it to the students the next day. So, we kind of had a motivation to learn it. And, we like thermodynamics.

Bale:

We used to go through the problems with the students. And so, it was like a demonstration class. Prof. Flengas handed out questions, and we helped the students answer the questions. And, that's how we slowly built a relationship together. We were students.

I was doing a Master's. I think, Arthur, at the time, was doing a PhD, was two years ahead of me. We got to know each other through that course. That's really where everything started to develop. But, why would we get involved with thermodynamics and calculations? Well, at that particular time, I had just arrived in Canada, and computers had just come out. So, we started in this in 1968. And so, I took a computer course. I know Arthur did some of his programming language for his thermodynamics because he knew how to do that as well using computers. And so, it was really a question of timing in respect to computers and good fortune that we were together. At that particular time, obviously, there's no way we'd realize we'd still be in the business 50 years later. So, that's how we started, and we slowly became good friends.

4:01 THE ORIGINS OF FACT/FACTSAGE IN MONTREAL - FACILITY FOR THE ANALYSIS OF CHEMICAL THERMODYNAMICS

Battle:

So, for people who don't know, explain what FACT is and what it stands for.

Bale:

FACT, well, we didn't start FACT then. We started FACT in Montreal many years later.

Battle:

Okay.

Bale:

We should maybe go into how that happened, too -- FACT. After Montreal, after then, Arthur went to MIT. I eventually got a job at Ecole Polytechnique in Montreal. Ecole Polytechnique was the engineering faculty of the University of Montreal. Arthur got a job there and became a professor eventually, and I joined him as a post-doc, and that's how we, with Bill Thompson from McGill University, that's how we started to work together on the FACT system. The acronym, for FACT, F-A-C-T, was faster. It came after M*A*S*H because M*A*S*H seemed like a good name at the time, from the TV show, so we called it F*A*C*T.

Battle:

Then, that stands for?

Bale:

Facility for the Analysis of Chemical Thermodynamics. That came about in 1976.

05:26 FACT - COMPUTER PROGRAMS THAT DO THERMODYNAMIC CALCULATIONS

Pelton:

Later, when we joined with ChemSage people and GTT-Technologies in Germany, they had a software called ChemSage. So, then we put them together and got FactSage.

Battle:

Right.

Pelton:

You asked what FACT is? FACT is a set of computer programs that does thermodynamic calculations based on Gibbs energy minimisation of an entire system. So, you can calculate the equilibrium state of a complex system. And, the data are taken from extensive databases, which are, for the most part, critically evaluated and optimized databases. These aren't just databases we've taken out of tables in the literature, but databases that we have used for a complex solution like a molten slag oxide. We look at all the data that are in the literature. We take a model which relates the thermodynamic properties to the structure of the solution so that we can then optimize or parameterize the data that are already known and then use the model to extrapolate into composition temperature regions that are unknown. We have many databases for different materials, steels, metals, oxides, and so on. With thermodynamic software that accesses these databases and that can present the results of many different ways, equilibrium calculations, multi-phase, phase diagrams of many different types, and all types of different paths one can take to equilibrium calculations. You can even cheat, sometimes induce quasi-equilibrium, and so on. So, it becomes a tool for engineering research and for industrial research and industrial practice as well, that's been built up over many many years.

Bale:

When we got started in '76, we were in a group of three of us—Arthur, myself, and Bill Thompson. We got a cooperative grant from the NSERC – the Natural Sciences and Research Council of Canada. That inspired us to work as a team between the two universities, and I think really what set us going was the NBS (Nat’l Bureau of Standards) meeting in 1977 when you had a conference on phase diagram, and phase equilibrium, thermodynamics, and that sort of inspired us to get going. We demonstrated our; I think we called it a Canadian Data Bank System, at that time, it was a workshop. We were just getting started in doing these particular calculations, and we'd do simple reactions. The program I had written, called the Predominance program, enabled you to take a system, in this particular case, the potassium sulfur oxygen system. We could do what we call predominance area diagrams as an option. We were demonstrating that in the workshop in Maryland and John Elliott passed by and Arthur had worked with John Elliot as a post-doc, and I had met him at MIT, and he came by and said, "Chris what are you doing?" I said, "Well, this is the predominance area diagram calculation of the potassium sulfur oxygen system." John said, "That's impressive; what systems can you do?" I said, "You can do any system you like as long as it contains potassium, sulfur, and oxygen!”

Battle:

You had to start somewhere.

08:41 FIRST COMPUTER COURSES - 1968

Battle:

Then going back to my original question, if I had to do these calculations, I would have had to scour the literature, if I want to do it right. Find the data available in that system. Do the analysis to figure out what's good data and what may not be good data. Maybe do some experiments. Have a model to extrapolate, and if necessary, interpolate. And, basically, you did all of that. So, a good chunk of FACT is, is you've gone through that, and we can trust that hey, this is the quality data available for that system, right? And then, the second part is we got to pull it out—the particular stuff you need for your calculations. So, the software that interfaces with the database. Right. So, I mean that could take me weeks to do- to reproduce-

Bale:

Yes, as you said, it would take a long time to get the data, and you have to know how to use and calculate it. So, it's sort of done for you. The FACT-FactSage system simplifies that operation.

Pelton:

And, even if you have the calculator, if you had all the numbers ready, the computer does it by iteration. Thousands of calculations coming into the results. Even if you had everything ready, it would take you a long time to do what the computer now does. So, this all came together at just the right time. We, well, we taught the thermodynamic course together, and we were both, we were about the same age as the students.

Bale:

He's much older.

Pelton:

He doesn't look it though.

Battle:

You've aged him.

Pelton:

The students say he's younger than you are. We were both the same age as the students, so the students had no respect for us at all, which was really good. If we said to them two and two is four, they made us prove it. So, that's where we learned thermodynamics. And then, at that time, computers were just coming out. He says he took the first course; I took the first engineering course at U of T in computers.

Bale:

I think for me, my first course.

Battle:

Your personal first.

Bale:

My personal first course in computing because I came from the University of Manchester, and we didn't have any computer courses that I remember. This is 1968, and, as a post-graduate, the first computer course, I think, given to the post-graduates. I remember I did really well on it. I thought wow, this is a cool subject. I didn't realize I was becoming a geek at that time. But clearly, I was. I used that programming to help my programming, and one thing led to another. It was good timing about computing and good fortune that we met each other, but we didn't realize at that time what was going to happen.

11:35 FIRST THOUGHTS ON A THERMODYNAMIC DATA COMPUTER SYSTEM

Pelton:

And then, I thought we could have some sort of thermodynamic data computer system, but that we would have to say give them- My idea was, at the time, was that anybody who wanted to use this, we would have to send him a pile of punch cards, and he can run it through his own computer at random because they didn't have what they call the timeshare. Interactive computing was not there.

Battle:

Okay, even the Mainframe-

Pelton:

No, not even the Mainframe.

Bale:

Back then, in 68' or 69', for example, to write a simple program that would do Gibbs integration, you'd use the box of cards, and there's two thousand cards in a box. So, if you were walking around with two boxes, you obviously had a really big program- You had like 3,000 lines of programming-[[[crosstalk]]]

Battle:

And, if you get them out of order at all or drop it, its death [[[crosstalk]]]

Bale:

If it was a damp day, you had to reread it. One of the consequences of that was that you would submit your job to get the card reader to read all the cards, you know. And, if you were lucky, you'd get the answer in 24 hours. You became a very proficient programmer because if you made one mistake on one line, you had to wait 24 hours to fix it, and do it all over again. So, you were very, very careful in your programming to get it right the first time. That was good. Taking 24 hours to get the calculations sounds ridiculous, but at the time, this was high tech.

Pelton:

People say well you got- we got into it at that time. But then, we must have been visionaries when we realized that interactive computing would be coming in and the personal computers. No, I wasn't a visionary at all. We were just a bunch of overconfident idiots. We liked what we were doing. I never thought that there would be interactive computing when it first came out. I thought gee-

Bale:

I remember in Toronto when we were working together. In experimentation where you're often controlling options to solve for potentials, and I thought it'd be really neat if we could have for any mixture, input mixture of CO, CO2, SO2, hydrogen, and so forth. There was the four elements carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, sulfur, any input mixture. If we had a program that could calculate the potential options to solve for or the other way around for a given potential of options to solve for. What would be the initial input to it? Solve for possibilities. So, we wrote something down. It was just simple elimination. I thought it was a fabulous program. At the time, it seemed earth-shattering. It seemed revolutionary, but nowadays, of course, that's nothing. I remember, at the time, being able to use the computer to do this very complex system, four-component system, to solve for option potentials. That was the first time I saw the value of the computer. And, I ended up using the computer calculations and some of Arthur's theories in my PhD. So, he had an impact on my research. He was two years ahead of me.

Pelton:

I'm still ahead of him.

Battle:

Was this all in Fortran?

Bale:

This was all in Fortran at the time.

Pelton:

Fortran II.

Bale:

It was Fortran IV.

Pelton:

Four? Well, you were advanced.

Bale:

I was more advanced than you.

Battle:

You were going to say- I'm sorry—some cutting remark.

Pelton:

Yeah, I probably-

14:56 TEACHING FORTRAN

Bale:

We eventually got to working together at Ecole Polytechnique, the three of us, in Montreal. We eventually proposed the FACT system. Everything at the time was done in Fortran. I ended up in the university, teaching Fortran for the electrical engineering department. So that's how I learned a lot of programming by giving courses to the students. My courses were in French too, so that was a bit of a challenge. That was fun, but that's another story.

15:31 THE START OF INTERACTIVE COMPUTING - MCGILL’S MUSIC

Pelton:

So, the interactive computing also just came at exactly the right time for us. Make FactSage a commercial product that people would phone in to, as you mentioned at the beginning, phone in through the acoustic coupler, through your modem. Young people, they don't even know what that is. You call up on your telephone, you put the telephone receiver into a little receiver, and it goes beep-beep-beep, beep-beep-beep. And, that sends sound signals down to the computer. You can imagine the speed of this hundred baud or something. So, that worked for a long time, and everybody complained about it, but that got us to- We had people connecting up from, we had one person from Perth Australia, which is as far away from Montreal as you can get on the surface of the Earth. So that worked, but endless complaints. Then personal computers came out in 1980.

Bale:

I want to interject something. We were very fortunate in the timing of this because Bill Thompson was the third person in that development. McGill University developed a computing system called MUSIC. Multi-User System for Interactive Computing. So, we could use our Decwriter, our terminals, to communicate with the central computer system. So, we were very fortunate at that time.

16:49 FIRST SATELLITE CONFERENCE TRANSMISSION

Battle:

There were probably only a few universities that had that at that time, maybe very few.

Bale:

Very few universities had that. So, we were able to take advantage of this new technology emerging from the university, and then we ended up sending, as Arthur pointed out, people would phone in, and McGill University then made their system available to the outside world. And, Arthur pointed out, for the calculations from Perth. Also, Rodney Jones, many times, tried to calculate ternary systems from South Africa. He knew the phone number by heart, and the speed at that time was 1200 baud. He was very persistent in certain calculations, but those were the mid-80s. We also demonstrated, at that time, for a conference transmission by satellite.

Pelton:

First time ever.

Bale:

For the first time ever. You want to explain that.

17:39 TRANSMITTING AROUND THE WORLD

Pelton:

Some group in California wanted to show- it was before the internet. It was at the beginning of the internet.

Bale:

In 1983, I think it was.

Pelton:

Something around there. This group in California had this system, and they wanted to show how we could transmit things around the world. So, there was a conference being held in Israel, in Jerusalem. At noon in Jerusalem, and they wanted us to- They had a big screen up there, and we were supposed to run the computer in Montreal, where it was four in the morning, and demonstrate- Chris would press the keys, and I was going to talk. So, we were giving a talk in front of this audience, and this was being moderated by the people in California who- So, people in California hadn't gone to bed yet. We had gotten up at four in the morning. The people in Israel had had breakfast and were watching this, and the whole thing just worked.

Bale:

I remember the guys in California had been up all day and celebrating, and they sounded like it.

Pelton:

They were half drunk, and they were laughing- they were actually high.

Bale:

And, what happened?

Pelton:

They were laughing away in the background.

Bale:

And, what happened was initially you had to transmit the same speed, and we were operating at 1200 baud, and they were operating at 2400 baud. These are technical details at the time. We couldn't really communicate, and, when we figured it out, there was this big roar in the auditorium in Israel that we heard. Hey! And, you could see this teletype thing going across the screen—a good luck transmission. So, the birds were coming outside to sing in Montreal, and we were all happy.

19:12 THE HIGH-TECH WORLD OF THE 1980S

Pelton:

This sounds silly, but, in those days, this was high-tech. We came home- think what we did. This was unbelievable, halfway across the world. So, as things came out, we were there at the beginning. We were there at the right time, for that sort of thing.

Battle:

Yeah, we're spoiled now, trying to explain to my children—things like card punch readers and all that.

Pelton:

Well, I watch my granddaughter talking to her grandfather in Hungary. I mean, she just dials him up, and he's there in 10 seconds.

Battle:

And, it sounds like he's next door.

Pelton:

So, she can't understand something like this.

Battle:

It wasn't always this way.

Bale:

At the time, when we were using the MUSIC system at McGill, we had to take our programs over there. There was no email, so you couldn't send it online, so taking the program from one computer to another involved putting it on a big tape. So, you had to formally present it to the tape manager at McGill, who would then load it into the tape reader and so forth. So, this was quite the challenge at the time, and it seemed really high tech. I remember; eventually, we ended up rather than using a tape; we brought the computer center a great big hard disk. I think you've got more power now on your hand calculator. The big mainframe computers, they were huge, and they were thousands of dollars. That was back then.

20:37 ENGINEERING, CONSTRUCTION, OR PSYCHOLOGY?

Battle:

So, let me go back a few years. Arthur, you were born in Windsor, Ontario. Now, are you from a scientific family? Was it fated that you would go into engineering, or were you the black sheep? [crosstalk]

Pelton:

Absolutely not. My father was a construction contractor.

Bale:

Well, that explains a lot.

Pelton:

He built houses and things, so, no, it wasn't.

Battle:

So, what made you go to Toronto and to go into engineering as opposed to trade or something?

Pelton:

You sort of fall into things. I wanted to be a psychologist. And then, a couple of people told me-

Battle:

Is that why you paired with Chris?

Bale:

That's psychiatry, not psychology.

Battle:

Well, close enough.

21:20 ENGINEERING SCIENCE COURSE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO

Pelton:

So, they told me all people who go into psychology do it because they're trying to work out their own problems or something. So anyway, I thought science was okay. Now I had no interest in engineering because I didn't think I was very practical; I couldn't turn screws and things. So, I wanted to go into pure science. So, I was going to take a pure science course. And then, my aunt said, “Well, there's this course at U of T called engineering science which sort of combines them both. It's an engineering course-“ [crosstalk]

Battle:

Kind of- [crosstalk]

Pelton:

[crosstalk] No. No, it's very heavy. Very heavy in basic sciences as well as being very heavy in engineering. It is for anybody who wants it. It's an excellent course. My son took it as well. Well, my son took it a few years later. And, he was always after me,” Dad, I want to go to Cornell. You want to send me to Stanford or something.” I said," I'm not going to spend $300,000 when you've got a perfectly good thing here." So, anyway, he then ended up doing his PhD in Stanford.

Battle:

Sounds familiar.

22:19 IF YOU WANT TO BE AN ENGINEER, LEARN THE BASIC FUNDAMENTALS

Pelton:

Yeah. He spent his PhD in Stanford in the U.S. He came back, and he said, “Well, all his students, all his colleagues, and first-year masters and doctorate, they're working like hell to learn the stuff.” He says, “I've already learned it.” It is one of the best courses, so I was really lucky to take a good course. It was my aunt who said take that course. It's the only thing she ever told me that was any good, but that was a really good piece of advice. I would recommend that course to anyone. I'd recommend it to anybody in engineering- Who was I talking to yesterday? Peter Hayes. We were saying that in engineering, you want to be an engineer. You want to do practical aspects but learn the basic fundamentals. That will then stand you in good stead in the future. If you learn, you can learn some of the practical stuff. But, if you don't understand the fundamentals, then you're not going to be able to learn anything more than what you already know. Once you know the fundamentals, learning different processes and so on. I always wanted to be a fundamental scientist. FactSage has been perfect because it goes the whole way. We have fundamental science. The models we're developing is like fundamental theory, and then we apply it. People use it which is--

Battle:

Gratifying.

Pelton:

It's very gratifying that you can do the fundamental stuff and get somebody to do something with this as well. So, I've never regretted taking engineering science, and that was the best. The best thing was actually getting into that course.

Battle:

So, your undergraduate degree is what?

Pelton:

Engineering Science, U of T, with the materials option.

24:05 OH, YES, I ALWAYS WANTED TO BE A PROFESSOR

Battle:

Now were you automatically thinking of grad school by then?

Pelton:

Oh, yes, I always wanted to be a professor.

Battle:

You weren't ready for the real world.

Pelton:

I never wanted to go to the real world. I never wanted it.

Battle:

You knew enough to not want to go to the real world.

Pelton:

I knew enough not to want to go to the real world. But, I realized, at a certain point, that I could sort of have the best of both, which I think I've managed to do with FactSage. So, I'm in the nice warm environment of academia, but we still have all our contacts in industry. And, we're doing something that I think is useful and commercially viable, so it worked out very well that way. But, no, I didn't want to be in the real world. I always wanted to be a prof. I always just kind of naively assumed I was going to get a job as soon as I graduated, which I did, but we can't count on that these days. Even in those days, you couldn't count on it. That's again, another bit of luck. Everything kind of came together.

24:59 WORKING WITH PROFESSOR FLENGAS

Battle:

And then, you worked for Professor Flengas?

Pelton:

Yes, he was my PhD supervisor.

Battle:

And how did that- I mean, I know the name, but I don't really know who he was?

Pelton:

Well, he was a chemist by training from Imperial College. He'd worked at CanMet for a while, and then he was a professor at Toronto. In Metallurgy/Materials Science, he did most of his work the molten salts. He was quite a fundamental guy. But, he was an excellent- I complained about him bitterly when he was my professor, but in hindsight, he really taught us how to do things properly. We had a really good group, and the group worked together, teaching each other. And, we did a lot of experimentation. I haven't done much experimentation in my career, but with the solid background in experimentation-

Battle:

It helps.

Pelton:

It helps a lot to- [crosstalk]

Battle:

To understand.

Pelton:

If you read a paper and somebody says the melting point was measured to a hundredth of a degree, you know that that's not real. That's not possible. So, I got a good background in that, and he was just very interesting. So, that got me interested in the thermodynamics. So, why thermodynamics? Well, because I had a professor who made it interesting.

26:19 BILL WINEGARD MADE METALLURGY/MATERIALS SCIENCE SOUND REALLY EXCITING

Battle:

A lot of people say that it took one teacher that- [crosstalk]

Pelton:

And, in engineering science, the way that course worked, the first two years were very general. And, then in the third and fourth year, you got a specialty. And, the professors from all the different specialties came and tried to tell us how wonderful their specialty was, and it was Bill Winegard who made Metallurgy/Materials Science sound really exciting. So, there wasn't much more to it than that. It wasn't like all my life I wanted to be a material scientist, but he just made this sound like fun. He made it sound like fun because it was the breadth of the field. I thought if I'm going to get into something big like electrical engineering, I'm going to be working in some narrow aspect of it because there's such a huge field. Whereas in Metallurgy & Materials you could go from physics to chemistry and cover a wider area of science and engineering, and a smaller field, a smaller pond, with more width, and that that kind of appealed to me. So, that's why I took it, and that worked out okay, too.

27:32 CLEVELEYS, ENGLAND - UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER

Bale:

My background is a little different. I was born and brought up in England. I spent my youth in a place called Cleveleys, which is on the west coast of England. And, I liked chemistry in high school, and I ended up going to the University of Manchester to do a bachelor's in chemistry. But, I wasn't so much into theory. I liked applied stuff. And, I remember in the chemistry courses, there was a course in physical chemistry, which is equivalent to or similar to the thermodynamics we now do. I think I was dead last in the class. I wasn't very good at theory, and so, I thought I should do something about this. Fortunately, at the time, the metallurgy department offered a joint degree with chemistry. So, I transferred from pure chemistry to chemistry and metallurgy and ended up with a joint chemistry metallurgy degree, bachelor’s after four years.

In '68, and this is where the timing and just coincidences are incredible, I went around Europe with a friend. We were visiting various countries. On my way back home to Cleveleys, I passed through the University of Manchester. It was about quarter to 5:00 in the evening, and I dropped off to see my old supervisor because, you know, I'd left university. I wanted to say bye. So, he said, what are you going to do? And I said, I'm not really sure, I like research. I'd like to travel around. And, he pointed to a poster on the wall. So, there's the University of Toronto. Why don't you go there? I didn't know where the University of Toronto was. I ended up, eventually, in Toronto. If I hadn't bumped into him on my way back going through Europe, and if the poster hadn't been there, and if the University of Toronto hadn't sent the poster out, and if the librarian had not posted the poster, we would never have met. When you think about it, you could go nuts thinking about the possibilities. You know they say all roads lead to the same destination. That's actually quite something.

29:33 UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO SCHOLARSHIP

Battle:

And what were they advertising? Engineering?

Bale:

Advertising metallurgy. Department of Metallurgy/Materials Science, and I ended up, I got a scholarship with Professor Jim Toguri. So, I went there in October 1968. He was a fabulous guy, fabulous professor. He worked with Flengas. They were in the same department, and I really learned a lot from Jim Toguri. He was as experimentalist and applied stuff, which is what I liked. I wasn't so much into theory until I got hooked into computers, and I thought, well, this is pretty easy, and I should use the computing in my science and so forth, and, eventually, I got hooked up with Arthur. So, my background was-- I also should point out I spent six months at Anglo American Company in Africa as a mining operator in the extractive, mineral treatment business. So, that was valuable, and I realized doing that-- I thought well, maybe I should go back to university and do the research; hence, I ended up in Toronto, and it's a decision I've never regretted. It was a great move, and this is where we met, and that's my story.

30:42 SUPPLEMENTING INCOME AS A COURSE DEMONSTRATOR

Battle:

And you ended up teach- we call teaching, TA'ing, teaching assistant.

Bale:

Yes, we were [crosstalk]

Battle:

In that thermo class that was taught by Flengas, perhaps? But, you were the ones who translated it to—

Bale:

Yes. Well, it was a way of supplementing your income as a student. We would be the course assistants or demonstrators, I think they called us. We were in the same class, and I think we did two or three years on the run. And so, we got fairly proficient in the thermodynamics, and this led on to the bigger and better things.

Pelton:

In the third year, Flengas was on sabbatical, so I actually taught his course that year as well as doing the laboratory.

Battle:

That's the way to learn, under fire.

Pelton:

The way to learn something is having to teach it. It's like the way to learn French is to have to be the lecturer.

Bale:

I mean teaching chemical thermodynamics, it's not the most exciting of subjects. That was a challenge trying to get the students involved and excited, and it became applied. We applied it to real situations, oxidations—

Battle:

Gets their attention.

Bale:

It gets their attention, and it got my attention, too. I thought, oh, this is really neat. I like this. I like this kind of stuff.

Pelton:

As I said, Professor Flengas was a very good teacher. It was his undergraduate course in thermodynamics that really got me interested, and that's why I went with him for a doctorate. He gave his course on the theory of thermodynamics, but every question on every test, every exam, was a numerical question. It wasn't describe one of these, describe some theory, develop the Gibbs-Duhem equation, or something like that. It was with real numbers, and you did a calculation. So, we brought the whole thing back—

Battle:

And, you didn't have calculators then.

Pelton:

No, we didn't have calculators. We had slide rules. We had open-book exams. He didn't believe that you have to memorize equations, but every question was a practical question with a numerical answer. I always ran every one of my thermodynamics courses through my entire career the same way. I never asked students to develop something. It was always, use it to extrapolate—

Battle:

Solve a problem.

Pelton:

Solve a problem. There are so many courses you get at university where you don't see-- Why am I thinking this? What is the point? If I'd only known, I would have listened. I had no idea. This especially applies to math courses, as you might know.

Battle:

It’s a requirement.

Pelton:

Why ever am I learning that? Gee, I wish I had listened to that. I thought that was a good teacher. A good teacher is important, very important.

Bale:

One of the things with FACT and FactSage is-- When I took thermodynamics and chemistry, and I didn't really like it. I wasn't good at it. Basically, what you were doing was learning a relationship, like Maxwell's, where you're just applying it here, calculating a heat, or an entropy, or whatever. I had no use. The thing with FACT and FactSage is that it does it for you. So, you've already done the calculation. Now, all you have to do is apply the numbers to the real-life situation. I think that's what really helps is that it gets away from the monotony of having to calculate these things in the first place. You've got the answer right there, and then you can apply it right away. You learn a lot coupling the thermodynamic values to the real-life processes.

Pelton:

As long as you understand what the computer is actually doing. But, it can go a little too far, like using a hand calculator to multiply two numbers when they don't quite understand the concept of multiplication.

Battle:

Or significant figures.

Pelton:

Or significant figures, yes. You can use FactSage, get an answer and just get nonsense because you didn't understand what you were doing to start. You have to be able to formulate the question.

Battle:

Yes.

Pelton:

And, in principle, be able to do it yourself, if the computer weren't there to do it for you. But, we haven't had too much of that. People that use it seem to catch on, and I think they actually learn from it. As Chris says, you learn thermodynamics because you see the answer coming out.

Bale:

You get a real feel for the numbers. I mean, you know, you say the heat is so many kilojoules, and you don't know what that is; you're lost. But, having seen it a few hundred times, it starts to mean something. You know, you get a feeling for what the number is. One part, one part per million, or one percent, or whatever of volume or kilojoules or BTU's, whatever you're dealing with. You get a real feel for the numbers. You get a better understanding, and, of course, we don't just calculate these numbers. We use these numbers in a meaningful way, like we produce phase diagrams, for example. We chart contours of data and so forth. So, the FactSage system produces these very useful outputs: phase diagrams, spreadsheets, and the like.

35:43 THESIS DEFENSE – POSTDOC WORK & INFLUENCES

Battle:

So, Arthur, you did your thesis defense when?

Pelton:

Doctorate in 1970.

Battle:

In 1970, and then you did a postdoc or couple postdocs. Weren't you in Germany, as well as—?

Pelton:

I did one in Germany.

Battle:

Now, did you plan to do postdocs or?

Pelton:

Yes, I wanted to do postdocs, see the world.

Battle:

Before you settle down, wherever.

Pelton:

Well, the postdoc in Germany was excellent. Professor Schmalzried was a brilliant scientist. I learned a lot about phase diagrams and thermodynamics.

Battle:

From their perspective.

Pelton:

From that perspective. That's helped a lot. It was the best year of my life. In Germany, a small town, wonderful time. Then I went to MIT, a little bit different.

Battle:

Meeting Chipman and Elliott.

Pelton:

Well, I worked with John Elliott, who was my supervisor there. I did meet Chipman and his people.

Battle:

They have a long family tree in extractive, including me. Yeah, I worked for John Hager and Bob Pehlke, who were both Elliott grad students. Maybe a little before your time, like mid to late '60s.

Pelton:

Well, Chipman was retired when I was there, but we had lunch a couple of times. Elliott was a very different man to work for than Spiro Flengas was.

Battle:

We want to hear about that?

Pelton:

No, maybe not [laughter]. I decided not to stay at MIT when they offered me a job, although it was in the hopes of a job offer that I went there in the first place.

Battle:

Oh, Okay.

Pelton:

When I got the offer, I decided I would have an ulcer by the time I was 40 if I stayed in MIT. Maybe we could put it that way.

Battle:

You mentioned–

Pelton:

Plus, they took the title Assistant Professor very literally [laughter].

Bale:

You mentioned Pehlke. I was influenced very much by his book on Unit Processes of Extractive Metallurgy – 1973, because it had all these nice computer programs in it.

Battle:

That's true [crosstalk]. Little Fortran things. [crosstalk]

Bale:

The Simplex algorithm and other various things they used, that was a big influence on me.

Battle:

That was the first book I had, too, before I went to CSM.

Bale:

So, I didn't know him, but his book influenced me greatly.

38:03 BECOMING A PROFESSOR & HAVING TO RELEARN FRENCH

Pelton:

Since we taught the thermodynamics course together at Toronto, we had this idea that we were going to write a textbook on thermodynamics, Chris and I. And Ecole Polytechnique was offering a job for a professor, which I didn't get the first year because there was somebody else. But, I told them, I said, “Well hire me as a Research Attaché, and Chris will come, and we're going to write this textbook on thermodynamics.” So, he came.

Battle:

And, that all came together.

Pelton:

It all came together, but we never did write the book because we got sidetracked on FACT.

Bale:

We got sidetracked in this computing thing.

Pelton:

At the same time, this- Two months later, this NSERC Co-op grant came out. We got together with Bill Thompson and started to work on that, and we kept pushing the book back, and back, and back. And, we never did write the book, but we ended up doing FactSage— Then, about a year later, I got a professorship. Then, a year after that, Chris had a professorship and so—

Battle:

And, of course, you'd been speaking French since you were young, right?

Pelton:

Yes, I learned French in Ontario High School, and I had to unlearn it in Quebec; then, I had to relearn it.

Bale:

When I arrived at Polytechnique, I knew it was French-speaking. I didn't know it was only French-speaking.

Battle:

So that's the crash course.

Bale:

That was a shock because I knew diddly-squat. I couldn't understand it. But, I knew the professorship job was coming up later after about two years—

Battle:

But, you did a postdoc first.

Bale:

So, I did a postdoc there.

Battle:

You had to learn French as you were doing—

Bale:

Well, I didn't need French to do the postdoc, but I thought I'd like to be-- I really enjoyed working with Arthur, and I enjoyed the environment, and I thought that I'd really like to have this job as a prof. I knew that one of the conditions of being a prof is that you had to be bilingual in English and French. And, I knew there would be a lot of French applicants from France who would not know English, and my English is not bad.

Battle:

English, not American.

Bale:

I had taken high school French, but I didn't understand any of it. So, I thought I've got to learn this. I used to sit down with a technician, Lucien Gosselin, every day, and I’d buy him a beer. Bonjour, Lucien, comment vas tu? And, I spoke to him every day for a bit and bought him a beer, and I picked it up. I used to listen to the television in French all the time, and that was the only way to pick it up. I'd have to say that, apart from working with Arthur, learning French is the most difficult thing I've had to do in my life.

Battle:

What a build-up. [laughter]

40:41 THE MOST DIFFICULT THING: TEACHING IN FRENCH

Bale:

The most difficult thing I've had to do. Arthur picked up French a lot quicker than I did. I'm not into languages. I'm more into this stuff, but I picked it up, and we both ended up teaching in French, and I think we're proud of ourselves. Can you imagine you're in a class in front of 80 students, and you have to speak in a foreign language, but you don't really speak it.

Pelton:

They were always very understanding.

Bale:

Very accommodating, the students. The French-Canadian students were wonderful. My hat's off to them. They were very nice and very understanding. The first class I gave, one of the students in the back stood up, “Monsieur Bale is this in English or in French?” I could have killed him [laughter]. They were very accommodating, and my hat’s off to them. And, this is where we learned French, by speaking to the students. We're engineers. We're not into linguistics, but we picked up on this, and we've won awards for teaching now, believe it or not.

Pelton:

People at Polytechnique, from the students to the staff and everything. That's the other thing that's come together very well. At Polytechnique, the administration has strongly encouraged professors in doing spin-off companies.

Bale:

Very supportive.

Pelton:

Very supportive of this type of thing. And, there are universities that say, oh no, you must remain in your ivory tower, and you're permitted to do four hours of consulting per week.

Battle:

Right.

Pelton:

You notice, the best universities in the world do not do that. At Ecole Polytechnique, they have a Centre de Developpement Technologique that promotes commercialization and so on, and this has been a tremendous help. So, they've been behind us all the way with these things.

Bale:

My hat’s off to them, and I hope they see this interview because we think very highly of them.

Pelton:

And the students, too. Some people from the ROC, that's the rest of Canada— ...think the French Canadians are very, very un-understanding, if you don't speak French, they just snub you, but it's just the opposite. They are very, very accommodating. The first year I was there, I wasn't a Professor, I was a Research Attaché, but they let me give a graduate course. I gave the graduate course in English. The students asked the questions in French, and it worked out very nicely. But, there was never anybody saying, hey, why don't you guys learn better French?

Bale:

No, never.

Bale:

Of the thousands of students, we've met, I've never had anybody complain. They've complained about your French, but they've never complained about mine. I'm just kidding. I wouldn't care. I actually wouldn't imagine that somebody at an English University, University of Toronto, who spoke English as badly as we spoke French, would have gotten away with the way we did. So, they were very, very understanding. It's been a pleasure to work there, and that's why we stayed there, because we could have left.

Battle:

You've had opportunities, I'm sure.

Bale:

We've had a wonderful environment to develop our system, the FactSage system.

- Computing and electronics

- Computing

- Data systems

- Engineering and society

- Engineering fundamentals

- Materials

- Metallurgy

- Metallurgical modeling and simulation

- Metals

- Molten metal and solidification

- Profession

- Engineering disciplines

- Metallurgical engineering

- Thermal engineering

- Engineering education

- Institutional histories of professional associations

- AIME

- TMS