Straphanger History: Pre-Subway Transportation

This page is the first in a three-part series about the construction of the New York City subway. This installment deals with pre-subway transportation up to the 1890s. The second page looks at Lewis B. Stillwell, electrical director of the IRT, and his role in designing the main power station and substations. The final page covers the actual construction of the subway.

2004 marked the 100th anniversary of the New York City subway, an electrical engineering feat. But mass transit got its start long before the subway made its debut. In fact, mass transit in the United States and Europe began in the early 1800s, with horse-drawn omnibuses and horsecars in eastern cities. An omnibus was a long four-wheel carriage that offered many passengers a very bumpy ride over short distances. Horsecars were street carriages on rails, pulled by a horse or mule, and introduced in New York City's Bowery in 1832. The precursor to the motorized streetcar, horsecars gained popularity in cities such as Boston, New Orleans and Philadelphia, and then in Paris and London, and later in smaller U.S. cities and towns. Steam railroads soon followed.

The Sprague System

Frank Sprague introduced the electric, street-car trolley system in Richmond, Va., on 2 February 1888. Sprague’s system could run more than 30 trolleys at the same time. It demonstrated his ability to overcome three technical challenges that other developers could not: transmitting electric current from a stationary power source to a moving vehicle; building a motor that could withstand repeated stopping and starting and constant speed changes; and mounting the motor so it could withstand violent jolts and lurches.

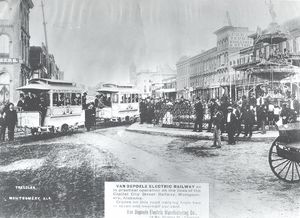

Sprague’s electric street railway system configuration became an industry prototype that was used on virtually all subsequent street railways. Interestingly, the Thomson-Houston Company, Sprague's closest competitor, modified an earlier Van Depoele system to include many essential Sprague electric traction design features. In addition, General Electric, Westinghouse and others developed electric traction systems based on the Sprague prototype.

The Richmond system’s 40 electric streetcars were equipped with dual, flexible supported traction motors and direct gear drives that ran on 12 miles of track. The system’s single-wire overhead conductor had a reversible, under-running pole trolley current collector.

Sprague’s Richmond system showed a skeptical general public and political officials that electric traction was convenient, reliable and safe. It represented a convincing technical demonstration, implemented on a large scale under extremely difficult topographic and operating conditions. The Sprague system also demonstrated to hesitant cable car and horsecar operators that it was feasible to build electric street railway systems that were large enough to provide significant transit service and be operationally practical. The system was more than three times larger than the average electric railway built up to that time, and it was composed of more than eight times as many self-propelled electric streetcars.

The system also pointed out to the conservative financial community that it was economically feasible for private investors to finance the construction of large, all-new electric street railway systems, including track, vehicles, power plant and overhead electric distribution — a major issue for the New York City Subway.

Introducing Rapid Mass Transit

The decision to phase out electric street railway service in Richmond and other cities was based on factors other than the soundness of the electric traction technology that Sprague perfected in Richmond in 1888. The Sprague system prototype continues to be used around the world as an integral part of balanced transportation systems, and it is embodied in the design of many modern Light Rail Transit vehicles. Sprague's system is an IEEE Milestone.

In 1887, only 35 miles of track using electric power existed in the United States. But Sprague revolutionized the world of mass transit. By 1895, 11,000 miles of track were in use. And by 1902, the country had almost double that track capacity.

The United States and Canada both had mass transit systems, but Europe was the clear leader in rapid mass transit. Great Britain, France, Scotland, Italy, Germany, Ireland, and Austria all had rapid mass transit systems. In fact, 2004 marked the bicentennial of the running of the world's first steam locomotive in England. And in the late 1800s, Paris had one of the first railways, a steam-driven train that looped around the outskirts of the city. In 1900, the Paris Metro opened, exhibiting beautiful subway entrances that played pivotal roles in establishing the "Art Nouveau" style.

On 10 January 1863, the world's first electric underground railway opened in London, and the City and South London Railway opened the world's first deep-level, electric railway on 18 December 1890. The latter was a mere three miles long and ran at an average speed of only 13 miles-per-hour. What's more, its tiny cars were stuffy, uncomfortable and loud.

Back in the United States, Cleveland had its first taste of electric-powered transit in 1884, when an experimental railroad opened along Central Avenue. In 1892, New York began street trolleys and elevated trains ("els") using direct current. The Chicago Intramural was constructed in 1893, but it was only temporary; it was built for the World’s Columbian Exposition and dismantled shortly thereafter.

Nikola Tesla's Role

During this same time, another development in electricity was taking place: Nikola Tesla was developing his alternating current generator, which became instrumental in the birth of the NYC Subway system. Part Two of this series discusses how the plans were set in motion.