Oral-History:James Spilker

About James Spilker

James Julius Spilker Jr. (4 August 1933 – 24 September 2019) was an American engineer and a Consulting Professor in the Aeronautics and Astronautics Department at Stanford University. He was one of the principle architects of the Global Positioning System (GPS), a co-founder of the space communications company Stanford Telecommunications, and at the time of his death, he was executive chairman of AOSense Inc., Sunnyvale, CA.

Born in Philadelphia in 1933, Spilker grew up in the Bay Area. He enrolled at the College of Marin and earned an associate's degree, in 1953, before transferring to Standford University where he earned his B.S., M.S., and Ph.D. degrees in electrical engineering. He received his doctorate in 1958 and took a post at Lockheed Research Labs where he worked on the precision tracking of satellites, a vital technology associated with Global Positioning Systems (GPS).

In 1963, Ford Aerospace hired Spilker as a director, and he designed and implemented the payload for the world’s first military satellite communications system. In 1973 Spilker co-founded Stanford Telecommunications Inc. and sold it in 1999. Between 2001-05 he was an adjunct professor of engineering at Stanford University. In 2005, he co-founded the Stanford University Center for Position, Navigation and Time, and became the co-founder and executive chairman of AOSense Corporation in 2006.

Spilker was an IEEE Life Fellow and served as chairman of the IEEE Technical Advisory Committee. He is also a Fellow of the Institute of Navigation (ION) and a member of the National Academy of Engineering (1998), the Air Force GPS Hall of Fame (2000), and the Silicon Valley Engineering Hall of Fame (2007). His awards include the Goddard Memorial Trophy (2012, the Arthur Young Entrepreneur of the Year Award (1987), the ION Kepler Award (1999), the Burka Award (2002), and the US Air Force Space Command Recognition Award. In addition, in 2015, he received the IEEE Edison Medal for contributions to the technology and implementation of the GPS civilian navigation system, and in 2019, James Spilker shared the 2019 Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering with three other GPS pioneers, Bradford Parkinson, Hugo Fruehauf, and Richard Schwartz.

Spilker's publications include: Digital Communications by Satellite (Prentice-Hall, 1977); GPS Global Positioning System: Theory and Applications. AIAA, co-edited with Bradford Parkinson, 1996; and Position, Navigation, and Timing Technologies in the 21st Century: Integrated Satellite Navigation, Sensor Systems, and Civil Applications (Wiley - IEEE Press, 2019) edited with Y. Jade Morton, Frank van Diggelen, James Spilker, Bradford Parkinson, and associate editors: Sherman Lo, and Grace Gao.

In this oral history, Spilker discusses his education, career, family, and philanthropy.

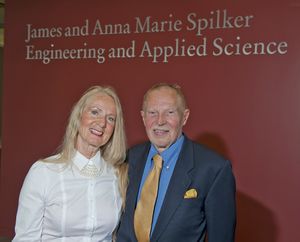

Please note, Mrs. Anna Marie Spilker participated in this oral history.

This oral history was made possible by support from Richard and Nancy Gowen.

About the Interview

JAMES SPILKER: An Interview Conducted by Michael Geselowitz, IEEE History Center, July 29, 2019

Interview #828 for the IEEE History Center, The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc

Copyright Statement

This manuscript is being made available for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the IEEE History Center. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of IEEE History Center.

Request for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the IEEE History Center Oral History Program, IEEE History Center, 445 Hoes Lane, Piscataway, NJ 08854 USA or ieee-history@ieee.org. It should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user.

It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows:

James Spilker, an oral history conducted in 2019 by Michael Geselowitz, IEEE History Center, Piscataway, NJ, USA.

Interview

Introduction and early life

Geselowitz:

I’m here at the Stanford University Faculty Club with James and Anna Marie Spilker. There are some other folks from the IEEE Foundation and Stanford at the table, and it’s a little noisy, but I think we can get started and move inside when we finish eating. We will of course cover your whole career, but your later accomplishments are well documented. I think people would be interested in how you got your start, so I’d like to begin with your early years and how you got interested in technology. You were born in 1933 in Philadelphia, correct?

Spilker:

Yes. I had a very difficult beginning. My father was in the navy and we moved around a lot—my sisters were born in Buffalo—and then he left my mother. We were in the Bay Area. My mother saw my interest in science, and she wanted me to have a chemistry set despite the expense. That’s how I really got my first exposure, and I did a lot of reading, and I was mostly self-taught. I also had no bedroom; no bed to sleep on. My sisters shared a room and I had to sleep in the kitchen. I had a cot in the kitchen. We had a kitchen door. The kitchen door was open. I could read Scientific American some days, but I had a very hard life.

Anna Marie:

He was physically challenged as well. He had vision problems.

Spilker:

This eye is legally blind. I’m partly helpless.

Geselowitz:

Yet when it was suggested to you earlier that you were blind in that eye—I won't say who said that—you covered your other eye, and you said, I can see Danny.

Spilker:

[Laughter]

Geselowitz:

Did you have trouble with your vision when you were younger also?

Spilker:

Yes. Let me tell you what happened when I got to Stanford.

Geselowitz:

I am anxious to hear that story, but first I want to learn how you got to Stanford. What was high school like?

Spilker:

Challenging. Besides my vision problems, I also got a lot of sinus infections.

One time I got 105 degree fever and, remember, I had no bedroom.

Geselowitz:

And the schoolwork?

Spilker:

Some of it was not exciting, but I had a science teacher and a math teacher who realized I was advanced, and helped me and gave me independent work to do.

Stanford and College of Marin

Geselowitz:

They encouraged you to apply to Stanford?

Spilker:

[Laughing] That wasn’t even a thought. They encouraged me to apply to College of Marin. I had some great teachers there, as well, who recognized that I was a prodigy and that I needed independent work.

Geselowitz:

This would have been 1951. Did those teachers encourage you to transfer to Stanford?

Spilker:

Oh, no, I graduated from the College of Marin.

Geselowitz:

You did graduate. With a bachelor's?

Spilker:

No, it was a two-year community college. I graduated with an associate’s degree and then applied to Stanford for junior status as a transfer.

Geselowitz:

You got accepted into Stanford? That’s very impressive.

Anna Marie:

Yes. Unfortunately, they didn't accept a lot of his credits, so he almost had to start from scratch. But he finished in two years anyway, and then went straight on for his Ph.D. Five years total for his PhD!

Geselowitz:

I of course want to hear about that. But first, I had interrupted you before, Jim. You had a story about when you first got to Stanford.

Spilker:

When I first went to Stanford I of course had some scholarships. These were small, local scholarships like Bank of America and The Rotary, but that covered the bare necessities. I mentioned that I was legally blind without special, very heavy glasses because my mom couldn’t afford them. When I showed up at Stanford I was in a class where there was no blackboard that I could see. I could not see the blackboard at all, there was no textbook, and my mom didn't have the money to buy me glasses. That's the truth. My mom couldn't afford glasses so that I could see the blackboard. Even though I was a very gifted student, I couldn't see, so it was impossible to do the work.

Geselowitz:

Wow. How did you compensate?

Spilker:

I didn't that particular quarter. I couldn't. But the next quarter, my mom was able to get me a pair of the glasses.

Geselowitz:

That solved the problem?

Spilker:

Yes, I did real well the rest of the time over the five years, but I had a hard time that first quarter. I didn’t tell you this yet, but remember I told you that I was prone to infections? In addition to not seeing the blackboard, I came down with a fever of 105 degrees again. I almost died.

Geselowitz:

And you had just started at Stanford.

Spilker:

Yes. I couldn't see and I had a fever of 105 degrees. I had to go to the hospital, so I couldn't do the exam.

Geselowitz:

Yes, it was very hard when it’s time for your final exam and you're in the hospital. In that era, also, I think people generally hid their personal problems from the world and from their parents, and I think that was part of it. You don't want other people to know your personal struggles. That was part of that culture. But the professors must have known that you were in the hospital.

Spilker:

I hid the eye problems, but they did know that I was in the hospital.

Geselowitz:

What did they do?

Spilker:

They just let me take that exam again, but I still couldn't read the exam on the blackboard. I still didn’t really know what the class was!

Geselowitz:

That's a very impressive story. We have been talking about women being underrepresented and there are certain ethnic groups that have been [unrepresented, too]. But it's hard to talk about poverty and being underprivileged. I think this is a very inspiring story for students to know.

Anna Marie:

We like to think we've improved a little as a country in terms of, like, making eyeglasses available for kids in poverty and kids who need glasses and stuff. I hope we're doing better. But I mean, that's really incredible what Jim accomplished, very inspiring.

Spilker:

Yes.

Geselowitz:

We’ll come back to your later involvement with Stanford later.

In my opinion, given your struggles, it's particularly generous that you're giving so much back to Stanford all these years later, especially that you're making scholarships and things available that weren't as available to you.

Let’s get back to the story of how, after all that hardship, you were able to get a Ph.D. on the “five-year plan.”

But, first, another question just occurred to me. As I am sure we will come to later in the interview, you are known as a champion of women in engineering. You mentioned sisters. I don’t believe they had physical issues like yours, but they also grew up in poverty. I was wondering if they also were able to become educated.

Spilker:

They had the poverty, but not the problems that I had with my eyes and fevers.

Anna Marie:

They did have the problem of being women in that era. His sisters are also accomplished. One got a masters at UC Berkeley. What was the master's in, Jim? Pharmacology?

Spilker:

Physiology.

Anna Marie:

From Berkeley. That’s pretty impressive, but she couldn’t find suitable employment because women weren’t employed in science in those days.

Geselowitz:

Interesting, thank you. Now back to your story, Jim. What happened after that first rough quarter?

Spilker:

Well, after I get better, I was able to make the dean’s list. I also got a scholarship from Hewlett-Packard. I worked really hard to catch up, taking something like nineteen credits per quarter. I was already taking graduate level courses so they slotted me right into the Ph.D. program.

Geselowitz:

Tell me about some of those courses.

Spilker:

Interesting that you should ask. They weren’t all engineering courses. I took an economics course, and after a few weeks the professor said I’d like you to be my grader.

Anna Marie:

Economics.

Spilker:

In economics. And he said I'd like you to be my grader. I said, well, I'd love to be your grader because I need the money, but I'm taking your class right now, so can I really your grader? He said, you're special; you have no problem being my grader. He later won the Nobel Prize!

Geselowitz:

Wow.

Spilker:

He said, I'd like you to get a Ph.D. in economics instead

Geselowitz:

Do you remember his name?

Anna Marie:

I think it was Paul Samuelson [Please note: the only Economics Nobel Laureate who was at Stanford in those days was Kenneth J. Arrow.]

Geselowitz:

I think it's clear from your background that you would want to pursue a Ph.D. in engineering

Spilker:

Yes.

Geselowitz:

Who did you talk to, or who was the first professor on the engineering side who said come work with me?

Spilker:

I forget, but that was not a problem. I remember that my lab partner, Lew Terman, encouraged me.

Geselowitz:

Wow, Lew Terman. I’m sure we’ll come back to him later. What was your dissertation work about?

Spilker:

In those days, Bell Labs was doing a lot of work in transistors. They did everything. And they won Nobel Prizes at Bell Labs. I had no problem getting a project from them, and there were plenty of faculty who could supervise it on the ground.

Geselowitz:

Your work was on transistors?

Spilker:

Yes.

Geselowitz:

Bell Labs supported it?

Spilker:

Yes.

Geselowitz:

Wow.

Spilker:

Technically, Stanford supported it, but they were getting the money from Bell Labs.

Geselowitz:

Bell Labs had a lot of money. Did you ever travel to New Jersey to visit your colleagues?

Spilker:

MIT was doing most of the work, so I was doing a lot of traveling to MIT. So I was doing a lot of studying with students at MIT who came to Stanford.

Anna Marie:

They didn't have the wormhole then, which they have now. That’s what they call a communications link here on the Stanford campus, where you can communicate directly with MIT without traveling there.

Satellite tracking

Geselowitz:

You did your dissertation on transistors with people from Bell Labs and MIT, and finished in 1958. What happened next?

Spilker:

At that point, I went to Lockheed Martin to work as an engineer. Then Ford Aerospace hired me.

Anna Marie:

Jim got the big corner office. He was a director. Ford Aerospace hired him as a director. That was 1963.

Geselowitz:

Just a few days ago, we had the big celebration for the fiftieth anniversary of the moon landing. Were you involved in any of the Gemini or Apollo stuff when you were at Ford Aerospace?

Spilker:

I was involved with the communication. My specialty was the timing and that was critical to the moon landing. If you’re off out there, you’re way off.

Geselowitz:

Wow.

Spilker:

All of the systems had to be concerned about the Van Allen radiation belts. The radiation belts affect all the electronics on board all of our satellites, so you had to pay attention to all of that.

Geselowitz:

Right. There were hardening issues. There were EMC issues (electromagnetic compatibility issues) because the cockpit is so small and you've got all the instrumentation. There's a lot of stuff; a lot of balls in the air for that project.

Spilker:

That's right. We had to be concerned about all of that.

Geselowitz:

Because of interference or EM effects on the transistors? What was the main concern?

Spilker:

That the effects on the transistors would lead to false readings. We had to be concerned not just about the effects on the electronics, but also the electrical systems. Even back on earth, we had to be concerned about the electrical effects on our country's distribution of electricity.

Geselowitz:

That’s interesting.

Spilker:

Most of my work was on satellite tracking. At Lockheed, I had already developed the delay-lock discriminator. At Ford I started working on the problem of the Doppler Shift.

Geselowitz:

An interesting thing for people to realize is that when Sputnik went up in1957, the Soviets had a transponder on it, because they wanted to detect it on each orbit. The Americans figured out that if you knew the velocity, you could use the Doppler Shift to figure out exactly where it was. That was sort of the beginning of the prehistory of GPS; it was just a single frequency beep.

Spilker:

Yes. One of my first books, Digital Communications by Satellite (Prentice-Hall, 1977), was about that. I sent a copy to Sir. Arthur C. Clarke, who had predicted satellite communications in an article back in the 1940s. I told him, here's the electronics that, I think, shows how to make your system work.

Anna Marie:

That was the time people realized that satellites could be used for location as well as for communication.

Geselowitz:

Right. Did he respond?

Spilker:

Yes.

Anna Marie:

He gave Jim a big thank you. He also invited us to go visit him!

Geselowitz:

In Sri Lanka?

Anna Marie:

Yes.

Geselowitz:

Oh, wow. Did you go?

Spilker:

No. I was always busy at home. I wrote five textbooks or part of textbooks. I’m working on one now on position, navigation, and time. Another one of the books would have been on encryption, how do you make the system encrypt properly? But, that book didn’t get finished

Geselowitz:

What methods were you using?

Spilker:

Oh, it was a whole series of things having to do with how you do the encryption.

Geselowitz:

Were you working on public key?

Spilker:

Instead, the work is a chapter in a book from the Pennsylvania Academy of Sciences that goes into details of that work, of that body of work. Of course, a lot of the encryption work was for U.S. military systems, so it is classified.

Anna Marie:

Jim had top secret clearance during the Cold War.

Geselowitz:

Have you ever met Bob Briskman?

Spilker:

I don’t think so.

Geselowitz:

I interviewed Bob last year. Now he’s best known for satellite radio. He’s the guy who founded Sirius Radio.

Spilker:

Oh, okay.

Geselowitz:

I love doing oral histories because you learn so much about people that’s not in their top-line public information. For example, I learned today about the obstacles you overcame to get to Stanford. Anyway, Bob was in military intelligence in the early Cold War and he was actually an on-the-ground guy building systems. He was actually in Berlin, and his job was to tap into the Russian communication—to tunnel under the wall, and to tap into Russian communications between East Germany and Russia. It's like, wow, that's more interesting to me than satellite radio.

Spilker:

Yes.

Stanford Telecom

Geselowitz:

I don’t think about encryption when I think about GPS, but you were doing this important encryption work. This is a good segue to ask about how you got into GPS, for which you are perhaps best known.

Spilker:

In 1973, I decided to start my own company, Stanford Telecom.

Anna Marie:

That’s right around when I met Jim. He was a dude, because that was what Stanford was like then, and he was broke because he had just started his own company. But, I figured if he got a Ph.D. at Stanford, he has to have possibilities. [Laughter] I had been dating a Saudi Prince, but I didn’t think I wanted to be a princess who was cloistered all the time, so I married Jim.

Geselowitz:

Probably a wise choice. [Laughter]

Jim, what made you decide to do your own startup? Was it the possibility of the GPS work for Brad Parkinson? What made you decide to start your own company instead of continuing to work for the big boys?

Spilker:

I just thought that would be a great opportunity.

Geselowitz:

When you launched the company did you start with a specific project?

Spilker:

Yes, as you said, it was GPS.

Geselowitz:

That was when Brad Parkinson was looking for contractors who could solve his problems.

Spilker:

Yes.

Geselowitz:

You thought you could solve it, so you spun yourself off and did it yourself?

Spilker:

Brad knew my work, and he was willing to hire a start-up, which is great.

Anna Marie:

Based on the resumes of the people in the company, right?

Spilker:

Oh, of course. It was really two of us, but mostly my work was known.

Anna Marie:

No, actually there were three of you that founded the company, but, yes, it was mostly you.

Spilker:

Yes. You know, Brad Parkinson was a great manager, but he needed technical teams to do the actual work. My team and I developed the signal structure. I had the mathematical background to do that. Hugo Fruehauf led the team that developed a sufficiently accurate oscillator. Richard Schwartz led the team that designed the satellite.

Geselowitz:

Wow.

Spilker:

Yes. The former Secretary of Defense, Bill Perry, helped me.

Anna Marie:

Yes, Bill Perry was a mentor to Jim for 50-plus years. Do you know of him?

Geselowitz:

Of course I've heard of him. Do you know a guy named A. Michael Noll, a Bell Labs guy who is a great friend of IEEE and its History Center? In the 1970s, he was sent from Bell Labs to be a liaison from the President’s Science Advisor to the Department of Defense, when Perry was Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering.

Anna Marie:

I don’t think we know him. Before Bill Perry went back to the government, he had a significant company called ESL, and Jim did a lot for work with them.

Geselowitz:

When and why did you decide to sell your company?

Spilker:

After twenty-seven years, it was time, and it was an opportunity, you know. We sold the company for half a billion dollars.

Geselowitz:

[Laughter] Who'd you sell it to?

Spilker:

To four different companies: Intel, Flextronics, ITT, and Newbridge.

Anna Marie:

Newbridge was purchased by Alcatel, which was purchased by Nokia. Nokia has Jim’s patents now. Nokia is 5G. They’re using Jim’s patents.

Geselowitz:

Wow. By the way, Bell Labs is now Nokia Bell Labs, so it has come full circle.

Anna Marie:

The good news is we were able to donate over 30 million dollars to Stanford based on those proceeds. Then we gave the government over 30 million dollars, too. It was after tax. The point is, it wasn't an arrangement where we didn't have to pay the taxes. We paid the taxes first, and it was after-tax dollars, not before-tax dollars in gift. That is different than how it’s usually done.

Geselowitz:

You'd mentioned earlier that you had three groups working with you. However, you've sold four pieces of the company, so somehow it grew and expanded from three to four groups.

Spilker:

This division was different, based on business needs. The original three groups had been combined because they were all doing classified work.

Geselowitz:

Interesting. Before we move on to all your activity in your “retirement,” I work for IEEE so I need to ask you about your involvement with the Institute. But first, let’s take a short break, so you can catch up your eating.

Anna Marie:

While Jim is taking a break, let me tell you one thing that you probably don’t know. He won the over-sixty, drug-free bodybuilding contest for the entire United States of America.

Geselowitz:

Really?

Anna Marie:

We have pictures to prove it. The doctors who see him now are stunned. They look at those pictures. He also came in third in a hundred-meter over-sixty track meet.

Geselowitz:

When did you take up bodybuilding as a hobby?

Spilker:

At, at age forty-something. When I was younger I was too small and sickly to take part in athletics.

Anna Marie:

He had the poor eyesight then, and he was just basically anemic.

Geselowitz:

You thought that bodybuilding was an area that you could compete in and also would be a way to work out and exercise?

Anna Marie:

No, it made him feel good. After eight, ten hours at Stanford Telecom, instead of facing the traffic—we lived in Woodside—we went to the gym for two hours, 8:00 to 10:00 p.m. People do that now!

Geselowitz:

The traffic is probably worse today.

Anna Marie:

Traffic is worse, yes.

IRE and IEEE

Geselowitz:

That was fascinating and I think important for people to know. Now that we’re re-settled, let’s get back to the main part of the interview. Jim, when did you become aware of either IEEE or its predecessor, the IRE?

Spilker:

Well, guess who submitted a paper to the IRE?

Geselowitz:

To the Proceedings of the IRE, the main publication?

Spilker:

The Proceedings of the IRE.

Geselowitz:

Would that be you?

Spilker:

Me.

Geselowitz:

What was the paper on, roughly?

Spilker:

It was a very important paper for tracking. It was the invention of the delay- lock loop.

Geselowitz:

Right. I think it's safe to say that it’s considered a seminal paper. Then did you become active, or did you just continue to publish using the IRE and the IEEE as publishing venues? Do you remember when that was published?

Spilker:

1961.

Geselowitz:

1961. Did you join the IRE at that time? I don't think you had to join to publish in those days. Were you a member, or at that point, were you just publishing?

Spilker:

I was an IRE member, and, well, then, of course, we formed the IEEE.

Geselowitz:

Right.

Spilker:

I started publishing papers for the IEEE.

Geselowitz:

In 1963, the merger of IRE and AIEE formed IEEE. You mentioned the Termans earlier, right?

Spilker:

Yeah.

Geselowitz:

They were very involved in IEEE. I was wondering if you got involved at all—like volunteering as an editor or a conference organizer—or if you were just more interested in research and publishing.

Spilker:

Fred Terman, of course, was one of the deans, and as I said, his son, Lew Terman, was my lab partner.

Geselowitz:

Right. He got very involved in IEEE.

Spilker:

He was president of IEEE at one point.

Geselowitz:

Did he try to get you involved?

Spilker:

Uh, no. I wasn't an officer, but I was involved with papers.

Geselowitz:

Did you attend conferences, IRE conferences or IEEE conferences?

Spilker:

Yes.

Geselowitz:

Did you find those useful for your work?

Spilker:

Oh, yes. We had papers that we gave all over the country.

Geselowitz:

And, eventually, all over the world. IEEE has become increasingly global in the past thirty years.

Spilker:

Yes.

Geselowitz:

I imagine that international scholars came to our conferences here also.

Spilker:

Yes. And I gave many talks around the world. For example, there was a big conference in Korea where one of the big executives in Korea gave prizes—I think it was a total of half a million dollars in prizes—to students for scholarships. And I was one of the speakers for that big conference in Korea.

Geselowitz:

Do you remember roughly what year that was?

Spilker:

I don't know exactly. I would guess it was at least ten years ago.

Geselowitz:

So you mentioned the communications transactions of IEEE. Do you consider yourself primarily a communications engineer, as opposed to other types of engineering? For example, there is an IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Society in addition to the IEEE Communications Society.

Spilker:

Yes.

Geselowitz:

So where do see yourself in the history of engineering?

Spilker:

Well, a broad area, because a lot of the work I do is in physics, physics problems. And of course, we had a Nobel Prize winner with Steve Chu at Stanford.

Geselowitz:

Right.

Women in engineering

Spilker:

Where he did work on cooling atoms? He worked with Mark Kasevich who is also one of my partners. We mentioned earlier promoting women in engineering. Well, we had a wonderful dean of engineering at Stanford, Persis Drell. She was a dean of engineering, and recently, we promoted a new professor dean of engineering, Jennifer Widom. The previous dean of engineering, Persis Drell, has been promoted to the provost of the university. A wonderful promotion. I’m extremely pleased that we have now had two female deans of engineering. The new provost is a former female dean of engineering, and Grace Gao, is a great new professor here. I believe it is extremely important to have these promotions. I hope IEEE will have new excitement for female engineers.

Geselowitz:

Right. There is a committee of the IEEE Board, the Committee on Women in Engineering, taking on those issues. Some people think their glass is half-full, some half-empty. As a historian, it seems to me, we've been hammering at this issue for, like, thirty or forty years, and we're not getting as far as we should as fast as we should. It's great that Stanford now has had two in a row, but if you look at the overall statistics, it’s not great. Of course, the more you get women at the top, the more young women will be inspired. But if you look statistically at women in engineering, it's not good compared to other fields. It still lags.

Spilker:

I think we at Stanford have been having a lead in this regard, and that's extremely important. The other universities should follow our lead. And as I said, maybe ten weeks, ten months ago, we had a big celebration for women in science and engineering. That's so very important to have women playing a lead role. I hope that the IEEE can do something with greater enthusiasm. It's so important to attract women in science and engineering.

Geselowitz:

Do you know Professor Andrea Goldsmith here at Stanford?

Stan:

I certainly do.

Geselowitz:

She's on the board of the IEEE Committee on Women in Engineering. You could talk to her about it and ask her what IEEE is doing and what we could do more.

Spilker:

She’s establishing a new fund to promote women in engineering here.

Geselowitz:

That's great, and it's great that Stanford is a pioneer as is the role that you're playing in that and getting these promotions. Actually, I don’t know if you’ve met Barry Shoop. He was the president of IEEE two or three years ago. He was the Chair of Electrical Engineering at West Point. He retired his commission, left West Point, and now he is the dean of engineering at Cooper Union College in New York City. I had lunch with him a couple of weeks ago to welcome him to New York City. I asked him how it was going. It was the end of his first year. He said the biggest challenge was diversity and the recruitment of women faculty. He saw this as his biggest challenge as the dean, so you are 100 percent correct.

Spilker:

What do you think can make a bigger impact?

Geselowitz:

I'll tell you what. It's your interview, so I'll ask you first. Then I’ll tell you what I think. So, what do you think we could do to make a bigger impact?

Spilker:

The first thing is to have the women as deans. And, another thing, have something else that we can show our students that you can actually do; something that can actually show our other students that there is a real leadership position that they can gather and do something similar with. If women can play a role as dean or some other leadership role, it can really help. For example, here's somebody that has a wonderful role, and she's a professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder. You probably know of her. Do you know any of the professors at the University of Colorado?

Geselowitz:

I know Mike Lightner who is a past president of IEEE, and at one point, chair of electrical engineering at Boulder. I don’t think I know anyone else.

Spilker:

There are two women that you should know there that are important deans. One of them is Jade Morton [Yu (Jade) Morton]. By herself, she done some marvelous work putting together a real international system for making measurements around the world of electronics. And, Penina Axelrad, a Stanford Ph.D., is chair of aeronautical engineering at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

GPS research at Stanford

Geselowitz:

That’s great. Let’s get back to your own research and its place in engineering history. You’ve been affiliated with Stanford for a very long time. Does Stanford have a center for GPS or anything like that? Where does GPS activity take place at the research level at Stanford?

Spilker:

I started a Stanford Center for Position, Navigation, and Time (CPNT). In order to do that, I needed to have professors active within this research center from a number of different departments, not just the single one. I needed to have a professor in physics, a professor in aero-astro, a professor in electrical engineering, and so on. I especially needed to have a number of full professors participating in this research center. The research center has been operating at the university for fourteen years now. Each year I have a symposium, and participants are not only Stanford students and professors, but professors from other universities, including from China and other countries. For example, one of the first years we were active, I had an invitation from China, from Tsinghua University to be a keynote speaker at a symposium. So, our center became very active with Tsinghua University. That was wonderful. Our center has hosted fourteen years of annual symposia here.

Geselowitz:

Are they still held today?

Spilker:

Yes, they're every November. One is coming up.

Spilker:

We have a big symposium. It is held at SLAC (SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, originally named Stanford Linear Accelerator Center). That way we get free parking.

Geselowitz:

[Laughter]

Spilker:

It has two auditoriums, one a 250-seat auditorium, and the other one is a 400-seater.

Geselowitz:

I have not been to SLAC, although I know it's not too far from where we are now. It's actually an IEEE milestone.

Anna Marie:

It's a what?

Geselowitz:

It's an IEEE Milestone. It’s part of the IEEE’s historical activities overseen by the volunteer IEEE History Committee and carried out by the staff of the IEEE History Center. I’m the director of the Center, and the chair of the History Committee reports to the IEEE Board of Directors. We recognize events that happened in technology history, and we put up a bronze plaque in the local IEEE Section where the event took place, and there is a dedication ceremony and so forth. This is called the IEEE Milestones Program. Next time you're at SLAC, ask to see the IEEE plaque.

Spilker:

Oh, wonderful.

Geselowitz:

On Thursday, we're going to dedicate another IEEE Milestone. We are placing a plaque at the Lick Observatory, and I understand you’ll be joining us there.

Anna Marie:

Yes, we’re planning to be there.

Geselowitz:

Oh, excellent. So you'll see what I'm talking about. You'll see the ceremony and the plaque. And, there’s one at SLAC.

Spilker:

Also at SLAC, there is a sort of hotel owned by Stanford University, so in some cases we can house free of charge some of our professors. When I started the Center in 2005, the funds came from industry. I got Professor Per Enge, who died last year, to actively participate and lead the center. Now there are multiple co-directors, including Brad Parkinson. The symposium is every year, and its outstanding speakers come from throughout the world. It's global. It's a global symposium, and it's brought lots of attention and funds to Stanford.

Geselowitz:

You have professors from around the world at the symposium. Have you had challenges with some of the work being classified in terms of you being able to interact with some of the foreign scholars?

Spilker:

Well, we're careful about that. But you know, every year for the fourteen years, I have had one of the speakers be an Air Force officer who is charge of the GPS program for the Air Force. We are able to do important presentations for the Air Force.

Geselowitz:

Right.

Spilker:

The Air Force doesn’t give classified briefings, but they have been able to give talks that are not classified and give important information to the civil personnel.

Geselowitz:

Wow, that's great.

Spilker:

We've been trying to do things that are very valuable to both military as well as commercial personnel.

Geselowitz:

Before lunch you also mentioned that you were working on a new book on PNT [positioning, navigation, and timing].

Spilker:

Yes, a two-volume technical book.

Geselowitz:

What's the status of that?

Spilker:

That's extremely important. I wrote most of the two-volume Global Positioning System: Theory & Applications (1996), and co-edited with Brad Parkinson. It won the Summerfield Book Prize from the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics and was read by a number of people. I was looking at my resume a couple years ago, and I said to myself, well, this book was written now twenty years ago. It's time to update it, so my suggestion is that we have a new two-volume book that includes the 21st century revolution in positioning, navigation, and time. I got with some of my friends and said let's approach IEEE and John Wiley and propose a new two-volume book. The two-volume book is now getting ready to be sent to John Wiley and IEEE.

Geselowitz:

Who's on the team for that book?

Spilker:

We have Jade Morton [Yu (Jade) Morton], the professor that I just mentioned earlier, as the lead editor.

Geselowitz:

The second editor?

Spilker:

Frank van Diggelen, who wrote a book on assisted GPS.

Geselowitz:

By the way, back in the day IEEE had its own press, but then they made a deal with Wiley to be, like, co publishers. Then they just basically made IEEE Press an imprint of Wiley. It's now an imprint of Wiley, and there's a liaison committee or whatever. It's essentially Wiley. IEEE puts the name on it if it's something important like this, then they really like to put their name on it. But, we don't actually publish our own books anymore like we did back in the old days. Anyway, it’s very exciting. Will you go on a book tour?

Spilker:

No. Well, we'll see. We might be printing this book in both Mandarin and English.

Geselowitz:

Initially, you're going to do it in English, but the plan is to translate it into Mandarin?

Spilker:

Yes. So that should cover a lot

Geselowitz:

A lot of the Earth's population.

Spilker:

A lot of it, right. Most of the Earth's population. That’s my goal.

Geselowitz:

After the United States, would you say China is the main center for PNT [positioning, navigation, and timing] kind of work?

Spilker:

Yes.

Geselowitz:

More than in Germany or other European countries that would have been the technical leaders in the twentieth century?

Spilker:

Well, of course, we're going to have German, French, and British authors as well.

Geselowitz:

Wow. That's exciting. Essentially, it will be a complete encyclopedia of GPS in two volumes.

Spilker:

It’s not a history book, though. It's a technical book for future generations to understand GPS.

Geselowitz:

Right, and now that you’re retired…

Spilker:

I haven't retired!

Geselowitz:

Well, my understanding is that since you sold your company, that the things you do for Stanford, you've been doing for free. You also mentioned doing some other consulting for the Colorado people for free. Many people would call that a retirement avocation rather than consulting.

Spilker:

Yes, most of it I do for free.

Geselowitz:

That’s amazing. That's a really a great way of giving back to the technical community. What does your wife think about this?

Anna Marie:

[Laughter] I'd like to see something coming in from the board of directors of some big company. Just enough funds for a horse.

Geselowitz:

I know you have a very large property, but you don't have a horse yet?

Anna Marie:

I think Jim would find it a competition.

Geselowitz:

[Laughter]

Spilker:

For my time.

Awards

Geselowitz:

As I said at the beginning of the interview, we know all your awards and so forth are documented on Wikipedia and the like, so I don't want to reinvent the wheel. Before we close, is there anything else that you want to make sure that you get on the record about your life and your career?

Spilker:

One of the things we feel strongly about is my award of the Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering.

Geselowitz:

Right. That’s an every-other-year prize, founded in 2013, and it was just announced that you will be receiving it for GPS, along with [Bradford] Parkinson, [Hugo] FrueHauf, and [Richard] Schwartz. The actual awards ceremony is in October [2019].

Spilker:

It’s extremely important because the Queen Elizabeth Prize is awarded based on the contribution of the engineers to society around the world. Since it is based on that broad level of contribution, the Queen's new prize is something really wonderful. It's different than the Nobel Prize. The Nobel Prize is generally, you know, for making a contribution to a particular area of science, whereas here, we're looking at broad, broad contributions and really looking at impact

Geselowitz:

It's interesting that you say that, because I've often heard talk in the IEEE Awards Board about why is there no engineering Nobel Prize. Engineers have won the Nobel Prize in physics and in biomedicine, but there isn’t a prize for engineers in engineering. There is one exception, the Hoover Prize, but that's U.S. only. That's a U.S. prize. The Queen’s prize and her advisors have really hit it on the nose.

Spilker:

Well, one of the really important contributions is who are the judges? The Queen Elizabeth Prize has a wonderful cadre of judges in my opinion. And I think that is extremely important. Who are the judges? The Nobel Prize, obviously, has wonderful judges as well.

Geselowitz:

I've heard some people say—and this is somewhat sad, I guess—that it’s the size of the prize that gets the attention, right? If you give someone a million pounds or a million dollars, the press all of a sudden wakes up, and they put it in the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle or whatever. If you give the person $20,000, it doesn't matter how great or wonderful they are, the press isn’t interested. It's good that the Queen got industry to back it, and to put the money where their mouth is.

Spilker:

It will still take a significant period of time before the Queen Elizabeth Prize has the same stature as the Nobel Prize, which has been around for a long time. We're hoping to see how we can raise the stature of the Queen Elizabeth Prize. And, I'll ask you that.

Geselowitz:

One way is by having the right recipients, right? That's one way that it will get attention. Although I agree with you, I think it's going to take time, just as the Nobel Prize has been around for over 100 years. However, having the backing of Queen Elizabeth is going to help it catch up eventually.

There's also a challenge--I mean, it's interesting, because you describe yourself almost as a--you're a mathematician and a physicist and an engineer. And you also mentioned about the issue of women in engineering before. And I didn't answer. So I'll answer a little bit now, not my whole answer.

After we turn off the tape, I'll give you my whole answer. But here’s the short version: Science does better, it's not perfect, but it does better than engineering in attracting women. I mean, in the old days, before the women's movement, you know, say, forty years ago, there were no women in science or engineering.

Science has done much better. And that's because engineering gets a bad rap. People don't understand what engineering is, how important it is, what engineers do that impacts humanity. People say, oh, so-and-so discovered something, that’s great. You built an electric car? So what? You know. So there's a general prejudice of the public against engineers and in favor of scientists. So there's a broader issue within society. That's why I was really happy when I first heard about the new Queen Elizabeth Prize a few years ago that it was actually going to be called the engineering prize and not a technology prize or some such.

The Queen is actually recognizing engineers and what engineering does for society. And that's really where the big impact is, in my opinion. So I don't have a good answer, but I think we just have to keep working on it. What have you been talking about with your colleagues, just some of your ideas?

Spilker:

It's going to take a significant period of time and work with the different places like the New York Times and other organizations like that before that changes. I don't know exactly how to do that. The New York Times and the Washington Post are crucial. How do we do that?

Geselowitz:

If I can be cynical, if the Queen invites some key reporters, key science reporters from key journalism, to come at her expense or the expense of the foundation that might help.

If the Queen wines and dines them at the conference and introduces them to the engineers, they're going to go back and write excitedly about it than if they say to their office in London, oh, look, there's this prize. You're the London bureau chief. We're not going to fly our top science person to London just for this thing, so you go cover it as London news, and then it's on page twelve or something. Right? So I hate to be cynical, but you know, journalists are people, too, so maybe if you butter them up a little bit, you'll get to them

Spilker:

What, if anything, has IEEE done to make something that has had an impact on the New York Times or the Washington Post?

Geselowitz:

What have we done? That's a good question. On the history side, which is my department, we try to remind the public of the great engineering accomplishments of the past, like the IEEE Milestone Program we were talking about earlier.

Spilker:

For example?

Geselowitz:

Well, right now, we're celebrating the moon landing. We always look for opportunities trying to get out into the public from a historical perspective.

Now this is maybe not as interesting to some people as cutting-edge technology; what's happening now. However, from our perspective, things that happened twenty, thirty, forty years ago, can be interesting, if we can make the public aware! Look, your cell phone didn't grow on a tree, right? This person invented spread spectrum, that person developed microwave theory, whatever. But people think this is a magic black box, right? So we're always trying, from a historical perspective, to interest the public. I have to tell you, though, it's very hard to interest mainstream media in history stuff, except real exceptional events like the moon landing, which is why we are using that as a hook this year. We also try to get to young people. We have a pre-university education program that puts history of technology into the classroom, into the history classroom, interestingly, which we call IEEE REACH. It's a relatively new program. We have about ten units. But, actually, one of the first of the units is on navigation.

Believe it or not, we actually focus on the magnetic compass and the sextant, right. How did Europeans learn to navigate? Why did the Europeans go to China, but the Chinese didn't go to Europe? What was the technological framework?

Then we compare it to, well, today, you just pull out your phone and your phone tells you exactly where you are.

After we complete the interview, I think you will want to speak to my colleagues from the IEEE Foundation who are here. The Foundation is very concerned about these issues.

Anna Marie:

You need to write a bestseller.

Geselowitz:

Well, that, too. [Laughter] In the meanwhile, Jim is there anything else you like to add before we turn off the tape and continue the informal conversation about the public visibility of engineering?

Spilker:

No, I think we’ve covered everything. Thank you.

Geselowitz:

Thank you to you and Anna Marie for giving IEEE so much of your valuable time.