Edison and Ore Refining

When Thomas Edison left the electric light industry in 1892 (a result of the merger of Edison General Electric with several other companies to form Corporation), he declared “I’m going to do something now so different and so much bigger than anything I’ve ever done before people will forget that my name ever was connected with anything electrical.” And what was this radical new interest that would catch the popular imagination and dwarf his accomplishments with electricity? Iron mining and ore milling.

At the time, the iron and steel industries were the largest in the world. But in the eastern United States, where Edison worked and lived, the best iron deposits had already been mined. Furthermore, new steel-making technologies demanded very pure iron ore, purer than the remaining eastern iron deposits could offer. These deposits contained so much rock and debris it was not profitable to turn them into iron ore. However, Edison had an idea. He reasoned that since iron is magnetic, he could use an electromagnet to separate the iron from the debris. Despite his grand hopes and best efforts, ore milling proved to be Edison’s greatest commercial failure.

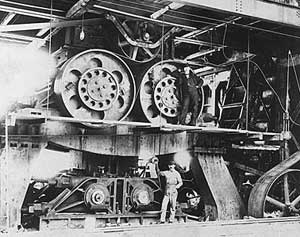

Edison first became interested in iron mining around 1880, and he received several patents that year for a device that used a powerful electromagnet to pull bits of iron out of a mixture of iron ore and sand. The Edison Ore Milling Company used this device for a few years, but it then went out of business because it could not attract customers for the ore. Edison’s interest was renewed in the late 1880s. He set up plants near existing iron mines near Bechtelsville, Pennsylvania in 1886 and Ogdensburg, New Jersey in 1889. The Odgensburg plant was constructed on a large scale, and included what was probably the largest ore-crushing mill in the world at the time. This mill pulverized the large chunks of ore that came directly from the mine. Edison planned to process 1200 tons of iron ore every twenty hours. The plant had three magnetic separators that could produce a total of 530 tons of refined ore. There was other equipment to re-refine what was left over to extract even more ore. But technical problems persisted.

In 1892, Edison shut down the mill in the hopes that replacing some of the equipment would improve production. He made changes to the ore-crushing machinery, installing huge rollers capable of turning out much larger quantities of ore. Still, problems persisted, and Edison had very few customers for the limited amount of refined ore his plant produced.

The iron ore business was nearly a complete economic failure for Edison, and he lost a great deal of money. To finance the operation he had sold his stock in General Electric. Now as his iron ore business crumbled, he had the added pain of watching the GE stock price rise and rise. If he had kept his GE stock, it would have been worth four million dollars. "Well," said Edison in response to this news, "it's all gone, but we had a hell of a good time spending it." The only long-lasting impact and financial silver lining of the experiment was that Edison was able to sell the ore-crushing technology he had developed to the owners of other mines. He also used it to make cement. Partly as an attempt to recover some of the huge losses of the iron refining, he opened the Edison Portland Cement Company in Stewartsville, New Jersey in 1899. Cement production proved more lucrative than ore milling.