The Solomons - Chapter 8 of Radar and the Fighter Directors

The Solomons - Chapter 8 of Radar and the Fighter Directors

By David L. Boslaugh, Capt USN, Retired

Guadalcanal Invasion

On 4 July 1942, U.S. reconnaissance found that the Japanese were building an airfield on Guadalcanal Island in the southern part of the Solomon Island Chain. An airfield located there would be a severe threat to Australia, and the Allies realized the island must be taken before the Japanese could finish the airfield. A large naval invasion force to be supported by three fleet carriers was planned to put the First Marine Division ashore on Guadalcanal to take over the airfield so a navy construction battalion could finish it. In January 1942, while on patrol approximately 500 miles west of Pearl Harbor, the fleet carrier Saratoga had been hit by a submarine torpedo and temporarily put out of action. She completed repairs at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard on 22 May 1942 and on 7 July departed Pearl Harbor to join two other carriers, Enterprise and Wasp as Task Group 61.1. This would be the Carrier Air Support Group of the Guadalcanal Expeditionary Force, which was designated Task Force 61, under the command of VADM Frank Jack Fletcher.

Each of the three carriers was assigned escorting ships, and each of these three forces was assigned a task force number. Saratoga and her escorts under VADM Fletcher’s command was designated Task Force 11; Enterprise and her ships, under RADM Thomas Kinkaid, became Task Force 16; and the Wasp group, under RADM Leigh Noyes, was Task Force 18. The other ships in TF-11 included: the Heavy cruisers Astoria, New Orleans, Minneapolis, and Vincennes, seven destroyers, and three fleet oilers. On the afternoon of 7 July, Saratoga’s air group flew out from Oahu to land aboard the ship, and since the ship was only eighty miles from Pearl Harbor, her fighter director officer LCDR Calvin E. Wakeman, got permission to break radio silence to run intercept drills with her fighter squadron, VF-5. [34, p.21] [9, pp.246, 248]

On 15 July, Enterprise with her escorts: the new fast battleship North Carolina, the heavy cruiser Portland, the AA cruiser Atlanta, and seven destroyers, steamed out of Pearl Harbor. Aboard Enterprise, LT Henry A. Rowe, former executive officer (XO) of the San Diego fighter director school, and now XO of the Camp Catlin radar and fighter direction school, was assigned temporary duty as assistant to the ship’s regular FDO, LCDR Leonard J. Dow. This assignment had been at the instigation of CINCPAC's air staff officer, CAPT R. A. Ofstie, who suggested to ADM Nimitz that this would be a good way for Rowe to get some practical experience while the Camp Catlin facilities were being built. Dow’s regular job was TF-16’s staff communications officer, and he assigned Rowe as full time FDO while he attended to the CXAM radar and other electronics. That afternoon the new FDO exercised Fighting Squadron 6 in repelling a mock dive bombing attack. On 23 July, Wasp, with TF-18 ships: heavy cruiser Quincy, AA cruiser San Juan, seven destroyers, and five transports, joined up with Task Force 11 near Tongatabu Island in the South Pacific. Wasp’s fighter director officer would be Lieutenant Frank G. Marshall. [34, pp19-20, pp.25-26]

The South Pacific Amphibious Force, designated Task Group 61.2, was under the command of Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner. He planned to have all troops and supplies ashore on Guadalcanal and the neighboring naval base at Tulagi Island by the end of the second day of the invasion: 8 August. During that time the three carriers of Task Group 61.1 were to remain within air striking distance of the two islands to provide air cover. It was found that the Japanese airstrip on Guadalcanal was not yet ready to receive aircraft. There were none there, however, there was a very definite possibility of air attack from the large Japanese base at Rabaul, which was within easy striking distance with their long range bombers. Furthermore, their protective Zero fighters could be fitted with belly tanks which allowed them to escort the bombers and give them perhaps fifteen minutes combat time over the invasion fleet. Also, Japanese aircraft carriers could show up at any time. The carrier fighter directors would be off at a distance and would be more concerned about protecting their own carriers. It was therefore essential that the landing force have its own fighter directors to direct local fighter defense. For this purpose, Wasp detached three aviators with fighter direction experience: LCDR Robert Strickler and LTJG Michael Elin of her fighter squadron, and LT. William O. Adreon of the scouting squadron. They were to operate from the Tulagi invasion group flagship, the attack transport Neville. Enterprise loaned LCDR William E. Townsend of her air department to perform FDO duty aboard RADM Turner’s Guadalcanal invasion flagship, the attack transport McCawley. Saratoga’s contribution was assistant FDO LT Robert F. Bruning, Jr., who would go aboard the cruiser Chicago that was assigned to remain beyond D+1 as an invasion force protection ship. On 30 July, in a TF-61 invasion rehearsal at Koro Island, LT Bruning exercised the Enterprise fighter squadron in practice intercepts. [34, pp.30-31]

RADM Turner’s amphibious force started putting the First Marine Division ashore on the islands of Guadalcanal and Tulagi on the morning of 7 August 1942 against light-to-moderate opposition. The three carriers steamed about fifty miles off the southern coast of Guadalcanal and sent dive bombers to help soften up the defenses for the marines. They also put a fighter CAP over the carriers and a Screen CAP (SCAP) over the outer screening ships of the invasion force in the channel between Guadalcanal and Tulagi. That morning the protective CAP over the carriers was drawn from all three of the flat tops and varied from sixteen to twenty-four Wildcats. LT Henry Rowe, FDO aboard Enterprise had control of the combined CAP, and had little more to do than have a few fighters check out an occasional unidentified radar contact. They found no bandits. The screen patrol over the invasion fleet ranged from eight to sixteen fighters under the control of LT Bruning on loan from Saratoga and now on board the cruiser Chicago. His watch was also fairly routine. In charge of directing carrier attack planes that were supporting the Tulagi invasion force, LCDR Strickler aboard the transport Neville was kept busy directing bombers and strafers to hot spots where the Marines were getting stiff resistance. LCDR William Townsend aboard RADM Turner’s flagship was likewise very busy directing attack planes supporting marines taking the partially completed Japanese airstrip at Lunga on Guadalcanal. By mid-day the invasion seemed to be going well, and there had been no enemy aerial resistance, but senior officers were still mindful they were within easy reach of strong Japanese air power at Rabaul. [34, pp.40-41]

Before the start of the Pacific conflict, the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) had the prescience to set up a ground-based network of Pacific island “coast watchers” having the job of keeping tabs on Japanese surface ship and air traffic in their vicinity. Many of them were RAN civilian reservists or retirees, and they were equipped with long range high frequency radios that operated on a special emergency frequency. One such coast watcher was Paul E. Mason, a reservist and now a planter located on southern Bougainville Island about 300 miles northwest of the invasion force. At about 1145 on D-Day he radioed a message to the invasion force commanders that Japanese bombers were headed their way. Forewarned, they began reorganizing their CAP, with highest priority going to protect the three carriers. Around 1230 a large blip to the northwest appeared on Chicago’s CXAM, most likely the Japanese aerial counter attack, and LT Bruning directed a division of eight CAP from the Enterprise air group to check it out. To his consternation, however, at 1300 he heard LT Hank Rowe, task force FDO aboard Enterprise, direct his CAP back to orbit over the carriers. This left only eight Wildcats protecting the landing area. Later the flight leader would complain that if he had not been redirected, he would have been in a perfect position to dive on the attack force. At the time Rowe, and most likely higher authority, had been concerned that the Japanese force was going against the carriers. The attack force, however, proceeded on to Guadalcanal, and when it became apparent that the carriers were not in danger, Rowe released more CAP to proceed north to Tulagi and Guadalcanal, but they would not get there before the bombers discharged their payload. [34, pp.46-47]

Now there were only eight fighters, stationed at 12,000, feet over the invasion force. Bruning probably would have put them higher but there was a heavy cloud layer ranging above 13,000 feet. The Japanese attack force was made up of twenty-seven twin-engine Mitsubishi G4M1 land based bombers, escorted by seventeen Zero fighters, and their mission was to destroy the ships of the landing force. Aboard Chicago, LT Bruning, at a little after 1300, vectored his eight CAP fighters to proceed on 310 degrees at 12,000 feet, and fifteen minutes later told them to come left by ten degrees. Within seconds the flight leader found that Bruning had put them directly below the bomber formation, and he tallyhoed twenty-seven bombers. He directed his fighter division to drop their belly tanks and turn on their gun and gunsight lamp switches. As the Wildcats started making their first gunnery runs, the bombers released their loads through the overcast, and then the Zeros showed up on top of the Wildcats. In the ensuing melee, ten more Wildcats from Enterprise finally showed up. Even six Wasp Dauntlesses, on Tulagi bombing missions also attacked the bombers and escorting Zeros. The final score was four Japanese bombers shot down & two ditched, and two Zeros shot down, at a cost of nine Wildcats and one Dauntless. Other than American aircraft shot down, the air raid could be considered a waste, the invasion fleet was hardly scratched. The aviators blamed poor initial positioning of their fighters by the fighter directors as the main reason for their losses. However, in a routine report to Pearl Harbor about how his Wildcat’s weapons had performed, Enterprise fighter squadron leader LT Louis Bauer noted that pilots wanted better fighters, especially faster ones. [34, pp.46-63]

On the afternoon of seven August, RADM Yamada, Commander of the 5th Air Attack Force at Rabaul dispatched nine Aichi D3A1 dive bombers to attack the invasion fleet. These craft did not have the range to make it back to Rabaul, and would ditch south of Bougainville where a tender and a flying boat would pick them up. They would not have fighter escort. The flight was not detected by the radars on the ships in the channel between Tulagi and Guadalcanal because the bombers followed along the northern coast of the islands and curved in from the north over Florida Island. Thus they were a complete surprise to the fifteen SCAP Wildcats over the invasion fleet. The surprise was to no avail. Only four of the bombers returned to their watery rendezvous, with no score on the invasion force. By this time, RADM Yamada was convinced American carriers were in the Guadalcanal area because of the large number of carrier based aircraft his pilots reported. He determined that on the eighth he would send out search planes to find the carriers, and at the same time launch an aerial attack force. The carriers would be the primary target, and the invasion fleet the secondary target if the carriers were not found. The attacking force would be composed of twenty-three twin-engine G4M1 bombers armed with torpedoes, covered by fifteen Zeros. This time the attack would not be a surprise because Australian coast watcher LT W. J. Read, a RAN reservist, saw them passing south over northern Bougainville and radioed a warning message.

Fighter director LT Robert Bruning aboard Chicago recorded the warning at 1044, and estimated the raid would be over the invasion force at about 1115. Five minutes later LT Hank Rowe, task force FDO aboard Enterprise, proposed to his seniors that the available twenty-seven Saratoga Wildcats and half the available Wasp fighters be launched as soon as possible to cover the invasion fleet. He recommended all available Enterprise fighters, and the remaining half of Wasp fighters be launched to protect the carriers. Fleet ship-to-ship communications in the Guadalcanal area had been very bad from the beginning of the campaign, and the order to launch the critical twenty-seven Wildcats did not reach Saratoga until 1135. In the meantime, LT Bruning aboard Chicago had sent his eighteen SCAP fighters up to 17,000 feet to await the enemy with an altitude advantage, although he did not yet see the raid on his CXAM. The fighters waited thirty minutes as their fuel ran critically low, and Wasp had to recall her fifteen Wildcats, while launching nine replacements ten minutes later at 1140. In the half hour it would take for the nine replacements to arrive on station there would be only three protective fighters over the invasion force. At 1141 Saratoga finally launched fourteen more fighters, and LT Hank Rowe aboard Enterprise sent them to 16,000 feet cover the invasion force. None of them would make it in time for the battle. [34, pp.74-76]

The reason the Japanese attack was later than expected was the continuing snooper search for the American carriers, which by 1150 had found no carriers, and the attackers were directed to the invasion fleet. Because they were coming in at 2000 feet from the north, mountains on Florida and Santa Isabel hid them from Chicago’s CXAM, and at 1155 shipboard lookouts gave the alarm. In response to coast watcher Read’s warning, RADM Turner had ordered the invasion force ships underway to open water where they could make defensive maneuvers. The attacking torpedo planes went through withering shipboard AA fire that downed many. Those that the ships did not get went on to encounter the three Wildcats over the invasion fleet who brought down four of the twin-engine bombers and one zero. Adding to the score, the rear gunner of a Dauntless on a bombing mission over Tulagi brought down another Zero. The final score in the ten minute attack was eighteen out of twenty-three G4M1 bombers and two Zeros downed. American losses were: one transport sunk, and one destroyer severely damaged by a torpedo. [34, pp.76-79]

The light Japanese opposition did not last, however, and the Japanese would eventually severely contest the islands culminating in a series of sea and air battles some of which would not be very kind to the Allies. By 20 August a naval construction battalion had the Guadalcanal airfield, now named Henderson Field, ready to land aircraft. An army SCR-270 radar had been in the hold of one of the transports, but the transport had to be withdrawn before the radar could be unloaded. The radar technicians/operators did get ashore and tried to resuscitate a Japanese radar they found on the island; to no avail. It would not be until 20 September that Henderson Field would get its first radar, but no fighter directors. Marine officer volunteers took over fighter direction until October when a team of four navy FDOs arrived. Their story will be told in Chapter 9 in the section titled “Fighter Directors Ashore.” The threat of an operating airfield on Guadalcanal forced the Japanese to send an invasion force of 1,500 men protected by three carriers, two battleships, nine cruisers and numerous destroyers to retake the airfield. The force, under the command of Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, included the heavy carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku, both veterans of the Coral Sea battle, and the light carrier Ryujo. The defending American force, under the command of VADM Fletcher, included the fleet carriers Enterprise and Saratoga, one battleship, four cruisers, and eleven destroyers. The first major sea/air battle, to be called the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, would take place on 24 August centered in an area roughly 200 miles northeast of Guadalcanal. [12, pp.19-20] [9, pp.248-250]

The Battle of the Eastern Solomons

The only significant action on 21 August came at about 1100 when Task Group 61.1 was cruising about 400 miles southeast of Guadalcanal and one of Wasp’s SBDs on inner air patrol discovered a snooping Kawanishi H8K flying boat. Even though the Dauntless was not exactly a fighter plane, it did have two forward firing fifty caliber machine guns, and LT Robert M. Ware did not hesitate to go after the giant four-engine flying boat, which was well equipped with twenty mm cannon as well as machine guns. He managed to set the boat’s port outboard engine afire which caused the port wing to burn off and the plane to hit the water in a fiery demise. No wonder some Japanese pilots referred to the Dauntless as a two-seat fighter. On 22 August at 1018, the Enterprise CXAM operator detected an unidentified target on a bearing of 315 degrees, range fifty-five miles, and estimated by fade chart at 8,000 feet. FDO LT Henry Rowe tried to contact his eight airborne CAP fighters, but heavy thunderstorms drowned out his transmissions. Rowe got permission to launch twelve more Enterprise Wildcats and sent one division west at 10,000 feet. Due to relative motion of the target, he gave them a final vector correction to turn to 180 degrees, which put the fighters within sighting range of the target, another four-engine Kawanishi, ahead and slightly above them. A 100-round burst flamed the aircraft, which shed its wings in flight. Again this showed that the CXAM could be used to very accurately vector fighters in on a single target; what was needed was a better way to show the multitude of data the CXAM could potentially present. [34, p.98, p.100]

At 1150 on the 24th of August, Saratoga radar detected a single target on approximate bearing 225 degrees, causing Sara’s fighter director, LCDR Calvin E. Wakeman, to break radio silence to vector a CAP division on 260 degrees at 12,000 feet. At 1157, Wakeman turned the division to 290 degrees and told them the bogey was fifteen miles ahead of them. Their tallyho was a new Type 2 Kawanishi H8K1 experimental flying boat 1000 feet above them and two miles ahead. The boat’s crew saw the Grummans and dived for a cloud layer. The flight leader had one two-plane section go beneath the layer, while he and his wingman stayed on top. At 1205 the big flying boat emerged from the layer at 500 feet altitude, and again fifty caliber bursts into an engine set the craft afire. It banked vertical and cartwheeled into the ocean. Snooper duty was turning into a very hazardous occupation, even with the Kawanishi’s heavy defensive armament. Task force radio intercept operators heard no transmission from the big flying boat and were quite certain it had not detected them. [34, pp.113-114]

LCDR Wakeman’s team at 1245 discovered another bogey south at about thirty miles range. He sent a division of CAP out at 185 degrees, angels seven. Because the bogey was twelve miles from the CAP and headed directly for them, he had them wait in an orbit. At 1253 the CAP tallyhoed, but first thought it was an American B-17 bomber flying very low at 200 feet. Wakeman asked for a verification of identity, and the CAP realized they had found a land based Mitsubishi G4M1 bomber, most likely on a patrol mission from Rabaul. The Mitsubishi pilot saw the four Wildcats and tried to evade, but they sent him into the ocean just seven miles from the task force. His demise was witnessed by the ship’s lookouts. This time VADM Fletcher was sure the Japanese knew where the task force was. [34, p.114]

The light carrier Ryujo launched an air attack against Henderson field at noon on the 24th which, at 1320, Saratoga’s CXAM operator picked up at a range of ninety-five miles on a heading toward Henderson Field. Saratoga tried to warn the island of the inbound attack, but severe atmospheric radio noise garbled the transmission. Ryujo carried mostly Zero fighters and the raid was composed of fifteen Zeros and only six Nakajima B5N attack bombers. Their mission was to destroy AA gun emplacements and fighters. Henderson Field did not yet have radar, so the marines maintained a daylight patrol of four Wildcat CAP with twelve more in ready status on the field plus a handful of Army Bell Airacobra fighters. At 1415 the CAP saw the raid approaching from Tulagi Island and broadcast the alarm. Ten more Grummans and two Airacobras took to the air, and marine AA spotters at 1428 saw six more Japanese twin-engine land based attack bombers join the fray. By 1450, marine wildcats had shot down eleven bombers and seven Zeros, and the marine AA gunners claimed one more that they thought was a Zero. In all, only seven Zeros and two Nakajimas made it back to Ryujo, at the cost of three Wildcats. The defenders had demonstrated that marines with Wildcats could more than hold their own against the vaunted Zero. The Saratoga radar sighting also served to give a fairly accurate estimate of Ryujo’s location, and Saratoga aircraft soon sent it to the bottom. Next, U.S. carrier airplanes engaged the Japanese troop ships of the Guadalcanal invasion force, with one ship sunk and the other two turned back. While Enterprise and Saratoga planes were working over Ryujo, Shokaku and Zuikaku had scouts in the air looking for the U.S. carriers. The Japanese still did not know Task Group 61.1’s location. [9, p.246, p.248, pp.252-253] [34, p.118]

Aboard Enterprise at 1338 on the 24th, fighter director LT Henry Rowe told his CAP leader “Bogey close in back of you”, and a few minutes later gave him a vector of 230 degrees to check out the contact he was sure was enemy. Sure enough, it was a snooping float plane thirty-five miles northwest of the task force. At 1400 the CAP leader tallyhoed and told Rowe the snooper was in the water. This time, however, the float plane’s radio operator had keyed off a sighting message that VADM Nagumo aboard Shokaku was reading by 1425. The report did not give an exact position, but it was not hard for Nagumo to deduce where the American carriers had to be. By 1500 Shokaku and Zuikaku launched a first strike wave of forty-two aircraft including twelve protective Zeros. In the mean time the pilots of two patrolling Dauntlesses found Shokaku about 250 miles north of TG-61.1, and at 1445 sent off a contact report. Next, they dove on the carrier and each dropped a 500-pound bomb, but the carrier’s skipper, alerted by lookouts just in time, ordered a radical turn that caused both to be near misses. Just a few weeks before Shokaku had been fitted with a Type 21 Air Search radar Model 1, and the two SBDs had been picked up by her radar operator, making this the first time a Japanese radar aboard ship had detected an enemy. The Japanese were probably having the same radar growing pains as early CXAM users, with inadequate interior communications, plotting space, and fighter direction procedures, with the result that the detection did not reach the bridge in time to be useful. The orbiting CAP was never warned. Unfortunately, the SBDs sighting report was severely garbled by atmospherics, with unreadable position and sender identification, and the most VADM Fletcher could get out of it was Japanese carriers were somewhere within search range of his scouts. [34, p.123-125]

Almost simultaneously at 1602, Saratoga and Enterprise CXAMs picked up a strong return bearing 320 degrees and range eighty-eight miles from the task force. Most of the force’s attack planes were out scouting, so the best Fletcher could do was to get ready to repel air attack. As task force FDO, LT Hank Rowe requested Saratoga to get all available Wildcats into the air, and vectored ten of them out on 320 degrees in hope of making an intercept far from the task force. A smaller radar contact appeared at 1604 at forty-two miles, on 315 degrees bearing. Not all friendly aircraft yet had IFF, so the contact could be a friendly scout or enemy snooper. Rowe sent ten more F4Fs out to check on the new bogey, which turned out to be a returning SBD with its IFF turned off. The long initial detection range gave VADM Fletcher enough time to clear his decks by launching a counter-strike, and then launching a large number of defending CAP. Then he started stowing explodable ordnance. Both carrier’s CXAM operators then lost the raid until it was in to forty-four miles. No radar fade zone was that wide, and this loss highlighted a serious problem with the CXAM. On this set, the receiver A-scope display was in effect “folded over” four times so the horizontal trace could represent a range of zero-to-fifty miles, fifty-to-100 miles, 100-to-150 miles, or 150 miles-to-200 miles. The operator used a “trip” button to determine in which range segment a target was located. The problem was that at ranges close to the ship there were usually many pips from nearby ships and airplanes, as well as “sea return” that had a masking effect. This helped obscure any target close to the ship, or near fifty, 100, or 150 miles range. It is very likely that the incoming raid probably reappeared more then once, but had been masked. This weakness was eliminated in later radars. [11, pp.22-23] [15, p.83] [34, pp.127-128]

From the initial range of detection and the CXAM fade chart, FDOs LCDR Leonard Dow and LT Rowe on Enterprise estimated the raid at 12,000 feet altitude. However, LCDR Wakeman, Saratoga’s FDO, estimated the raid at 18,000 feet, and called Enterprise with his estimate, but on board Enterprise the call was garbled and interpreted as 8,000 feet. When the raid again showed on the Enterprise CXAM it was again estimated at 12,000 feet, and the misread 8,000 feet from Saratoga gave LCDR Dow confidence that the raid was no higher than 12,000 feet. He had a CAP of thirty Wildcats stacked at eight, ten, and fifteen thousand feet over the task force, and he vectored eight of them out to intercept at 12,000 feet. They sighted the raid thirty-three miles out, but at an altitude considerably above 12,000 feet, and they had to contend with protecting Zeros while making their way up. They managed to shoot down a number of Aichi D3A dive bombers and Zeros, but twenty-four dive bombers broke through to Enterprise. Unfortunately, rate of climb was not one of the Wildcat’s strong points and no more than seven Wildcats were able to engage the bombers before they began their dives. Ten more Wildcats caught up with the bombers during their dives. Three of their bombs scored on Enterprise, and started fires. Fortunately, the ship had been cleared of exposed ordnance and vulnerable gasoline, so damage control teams were able to have the ship ready to recover aircraft within an hour. The attack planes launched by the American carriers failed to locate Shokaku and Zuikaku, but on a happier note a CAP section that had been vectored northwest at forty miles managed to turn back nine Japanese torpedo planes. [11, p.22-23] [15, p.83]

With the sinking of a Japanese light carrier and a destroyer as well turning back an invasion force at the cost of the damaged Enterprise, the Battle of the Eastern Solomons was adjudged a tactical victory. However, there was still senior officer unhappiness with fighter direction, primarily with their equipment. In his action report, Saratoga’s CO noted that IFF had been of almost no use. He stated that many PBY patrol planes and B-17 bombers in the area either had faulty IFF gear or they were not using it. Further, his aircraft IFF sets had many malfunctions. Exacerbated by atmospheric radio noise, the fighter net medium frequency radio circuits had been totally unsatisfactory. Admiral Nimitz, in his action report, stated, “Few of the orders from the Fighter Director Officer reached the fighters and little of their information reached him.” The pressing need for a height finding radar was again brought out. VADM Fletcher noted that fighter direction had been better than past actions, but still needed improvement. [11, p.23] [34, p.163]

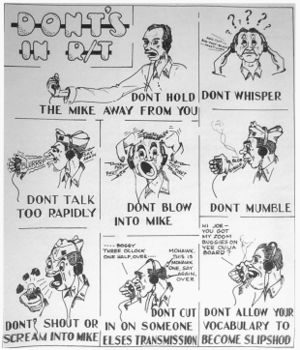

There was also a human relations problem. This centered on the fact that the Enterprise FDO had depended on Saratoga fighters as part of his CAP, and had to work with pilots he did not know. In spite of standard procedures and vocabulary there had been misunderstandings and friction. To solve this, Saratoga’s CO proposed that one carrier in a task force should carry only fighters and have the duty of protecting the entire task force. The other carriers would carry mostly bombing squadrons with only a few fighters. Other task force commanders seconded the idea. ENS George P. Givens, assistant FDO on Enterprise noted another problem, lack of radio discipline among some of the more inexperienced fighter pilots. With all CAP pilots and all FDOs using the same radio channel, the net had become so crowded that often an FDO could not transmit a critical item of information. Also, whenever two nearby users keyed their mikes at the same time it would cause a squeal that allowed nobody to transmit. It had happened a number of times during the air battle. LT Henry Rowe, whose full time job was executive officer of the Camp Catlin fighter director school, exclaimed that the flight training curriculum needed to emphasize pilot radio discipline. Senior pilots, in support of their exuberant younger pilots, said radio chatter was good for teamwork and improved morale. In the long run, radio discipline would prevail. [11, p. 23] [34, p.133]

The Battle of Santa Cruz

In late October 1942, the Japanese started a new push to retake Henderson Field, which by this time was surrounded by enemy jungle fighters. A large Japanese sea force including four battleships, the fleet carriers Shokaku, Zuikaku, the light carriers Junyo and Zuihio, ten cruisers, and twenty-two destroyers, had the dual mission of supporting the Japanese soldiers ashore and engaging the U.S. South Pacific fleet in a decisive sea battle. Admiral Yamamato’s orders to Admiral Nagumo in command of the striking force were, “Annihilate any powerful forces in the Solomons area.” The opposing American force, under the command of Rear Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, consisted of the carriers Enterprise and Hornet, the new battleship South Dakota, six cruisers and four destroyers. Wasp had been sunk by submarine torpedoes on 15 September, however, Enterprise’s damage from the Battle of the Eastern Solomons had been repaired by 16 October, and she was back on active duty. RADM Kinkaid hoisted his flag aboard Enterprise as officer in tactical command, meaning her fighter director officer would be in charge of task force fighter defense in the forthcoming air battle. Vice Admiral William Halsey had just been named Commander, South Pacific Area (COMSOPAC) and had ordered Enterprise’s experienced FDO, LCDR Leonard Dow who was also his staff communications officer, to his headquarters at Noumea on New Caledonia Island to clean up some communications problems. Also, a number of Dow’s experienced radar plotters and radar men went with him. CDR John H. Griffin, Officer in Charge of the Pacific Fleet Radar Center on Oahu, was temporarily riding Enterprise on RADM Kinkaid’s staff, and was designated to take CDR Dow’s place as task force FDO. Although an expert in the theory of fighter direction, Griffin had never actually directed fighters in combat, and conditions of radio silence would give him no chance to work with his new team and fighter pilots in live drills. [15, pp.88-89] [9, p.255] [36, VIII: p.147]

A little after midnight on 26 October a patrolling PBY Catalina equipped with a British ASV Mark II radar set located Nagumo’s flotilla a few hundred miles northwest of the Santa Cruz Islands. By this time ADM Kinkaid’s task force was north of the Santa Cruz Islands and within attack range. At first light he launched sixteen Dauntless dive bombers on a combined scouting/attack mission that found the Japanese force. In spite of six protecting Zeros, three of which the SBDs shot down, they dove on Zuihio and placed two bombs into her flight deck. The hit rendered her unable to recover aircraft, and she retired from the battle to seek repairs at Truk. Nagumo had also launched attack aircraft at first light and the two opposing air strikes passed so close to each other that there were some targets-of-opportunity aerial fights. The Japanese raid approached the two American carriers at 17,000 feet at about 0900. Enterprise was under rain clouds, so Hornet, about ten miles away, became the raider’s object of attention. [15, p. 89]

When the American attack force spotted the Japanese raid they radioed their sighting back to their carriers so the task force was in readiness. CDR Jack Griffin had already stationed seven Wildcats at 10,000 feet over Enterprise and four more to the south between Enterprise and Hornet at the same altitude. He had chosen that altitude to conserve fuel and pilot’s oxygen, with the plan that when the raid appeared on radar, he would send them higher if necessary. Meanwhile, on Hornet, ten miles to the southwest, her FDO, Lieutenant Alan F. Fleming, had been delegated to control Hornet’s CAP. Fleming had been Hornet’s flight deck officer during the battle of Midway. He said he had complained so much about fighter direction during that engagement that his seniors finally told him he was going to take the job, and sent him off to CDR Griffin’s fighter direction school. He also placed his CAP of eight fighters in orbit at 10,000 feet over Hornet. The oncoming Japanese raid had not yet registered on the CXAMs when at 0830 a pilot in the passing strike forces warned the task force of imminent dive bombing attack.

RADM Kinkaid ordered Hornet to launch all fighters immediately, and soon there were twenty-two Wildcats over the ship, some already at 10,000 feet and the rest climbing. Aboard Enterprise, CDR Griffin also heard airborne radio chatter that indicated the Japanese raid was closing in off to port, although his radar operators could see nothing on their scopes. Griffin did not realize the chatter came from a distant flight and that the reference to port was relative to their direction, not the task force’s direction. His port was to the south and at 0842 he told some of his CAP to investigate to the south, probably high. Neither FDO knew it, but both of their CXAMs were performing very badly that day. The one CXAM that was working well was on the cruiser Northampton in Hornet’s screen, and at 0841 that ship detected a large incoming bogey on 295 degrees at seventy miles. Confident that radar operators on the two carriers had seen the same blip, Northampton’s CIC team did not radio the sighting but rather passed it to Hornet by flag hoist, with many minutes delay. CDR Griffin on Enterprise never received the information. [34, pp.385-387]

The raid finally showed on Hornet’s CXAM at 0855, and by this time it was in to thirty-five miles, bearing 260 degrees. LT Fleming vectored two divisions of his CAP westward, and on their own they decided 10,000 feet was probably too low and began to climb. A few minutes later, Enterprise radar operators saw the raid at forty-five miles, and Griffin sent two divisions out on heading 255 degrees. The Hornet fighters, at 0859, were the first to tallyho, and reported to Fleming, dive bombers at 17,000 feet, and it was a large raid of fifty-three dive bombers, torpedo bombers, and fighter escorts. Fleming quickly sent out seven more Wildcats to help, and CDR Griffin urged his eight CAP to climb! Fleming’s fighters met the raid at twenty-five miles out and at their level, but the attackers had already started their dives. The Wildcats were able to pick off a few, but most broke through and went after the only carrier they could see: Hornet.

Meanwhile, under an obscuring cloud bank ten miles away, CDR Griffin on Enterprise was trying to understand the attack pattern; specifically, were they closing on Enterprise also? He radioed Fleming asking if his radar showed more than one attack group, to which Fleming replied, only one spread out group and all attacking Hornet. Given that information, Griffin sent half of his CAP to help their sister carrier. Hornet lookouts sighted the raid at 0905, and at 0909 the ship’s five-inch mounts opened fire. Twenty-five of the attackers were downed by AA fire, one of them crashing into Hornet’s flight deck. The carrier then took three hits from dive bombers. At 0914 one of the torpedo planes scored with a torpedo into the starboard side amidships, and within twenty seconds a second exploded further aft on the starboard side. Hornet was soon dead in the water, and not able to either launch or recover aircraft. Of the fifty-three Japanese planes in this first attack wave, only fifteen made it back to their carriers. This was at a cost of six Wildcats. By 0948 the raid had dispersed and Enterprise began recovering Hornet’s aircraft as well as her own. [34, pp.387-408]

Admiral Nagumo was convinced that, even though his first strike wave had not seen a second American carrier, that there was a second. In addition to other clues, returning pilots said they had heard two different fighter directors controlling fighters. Nagumo’s second strike was composed of two separate groups of torpedo and dive bombers launched about forty-five minutes apart. The first group from Shokaku was composed of nineteen Aichi D3A1 dive bombers escorted by five Zeros flying at 16,000 feet. The trailing Zuikaku group was made of seventeen Nakajima B5N2 attack bombers, that could be armed with bombs or torpedoes, with four covering Zeros. In the mean time, Enterprise had come out from under cover of the rain squall, and at 0937 a Zuikaku search plane spotted the Enterprise task force and radioed its position. The battleship South Dakota’s radar team detected the lead group at 0945 twenty-five miles to the north. Aboard Enterprise, FDO Jack Griffin was trying to sort out confusion. Because of his CXAM’s poor performance he was not certain where his CAP airplanes were, all he knew was bogies were coming from the north. He told all CAP to look toward the north and northeast, but they did not see the attackers concealed by clouds. Furthermore, at 12,000 feet, the CAP was well below the high flying dive bombers. Only two of the Wildcats were able to engage the bombers before they nosed over for attack, and Enterprise lookouts warned of the attack at 1015. [34, pp. 408-413]

Enterprise was well protected by AA fire from her escorting ships, in particular by the new battleship South Dakota that bristled with five-inch AA mounts. Enterprise had also recently had her obsolete 1.1-inch AA guns replaced by fast firing quad mounted forty mm cannons that proved to be very effective. In all, Enterprise took three non-disabling hits from the first group, at a cost of six Japanese dive bombers. Twelve of the defending Wildcats never saw an enemy plane. Pilots later reported from hindsight that they would have been in a good attack position but were never vectored against the bandits, which they could not see. At 1040, the Zuikaku strike group of seventeen torpedo bombers appeared as a large blip on Griffin’s CXAM. He estimated their altitude to be high, meaning they were probably more dive bombers, but a sixth sense told him they must be torpedo planes. He vectored out his CAP at 1044 and told them to look for “fish” (meaning torpedo planes). The attackers had split into two groups to hit the carrier from both sides and on this occasion, Griffin had put his fighters right in the path of a flight of eight of the attackers, of which only five were able to continue their torpedo runs. The eight other torpedo planes and one unarmed command plane circled Enterprise to come in from the west. Three of the eight were promptly shot down by a combination of AA fire and Wildcats, but four managed to launch torpedoes against the carrier. By CAPT O. B. Hardison’s adroit maneuvering, the ship avoided all four. The remaining plane launched a torpedo at the battleship South Dakota with no score. Of the five remaining torpedo planes coming in from the north, all launched torpedoes against the carrier but with no score, and two were shot down. Final tally was eight torpedo planes out of seventeen succumbing to AA fire and Wildcats. [15, p. 89] [9, p.255] [11, p.23] [34, pp.413-426]

At 1058 another casualty aboard Enterprise became apparent, probably a delayed reaction to the shock and shudder of the three bomb blasts. The CXAM’s flying bedspring would no longer rotate. Now, Griffin had no idea where his eighteen airborne fighters were, and all he could do was to tell the CAP to stay near the ship. Radar officer LT Dwight M. B. Williams climbed up the mast to the antenna. There he found parts of the train rotating mechanism out of alignment. So he could use both hands to realign components, he lashed himself to the array. However, someone below decks got the word the antenna was repaired and turned the rotation back on while Williams was still fastened to the antenna, and he got a ride he really did not want. Officers in nearby sky control saw his dilemma and got word down to the radar shack to cease rotation! Williams gratefully lowered himself to the Island, and by 1115 the CXAM was back in operation [34, pp.430-431]

At about the same time as the attack on the two U.S. carriers, a group of Hornet dive bombers found Shokaku and, evading her protecting Zeros, put four 1,000 pound bombs into her flight deck. The carrier had to quit the battle and spend the next nine months in a shipyard. Hornet SBDs also severely damaged the cruiser Chikuma. While damage control crews were at work in Hornet, she sustained another hit from torpedo planes, forcing the abandon ship order. Once abandoned, the carrier took two more torpedo hits from American destroyers trying to scuttle her, but she would not sink. Next they tried gunfire, but had to leave the area to avoid the oncoming Japanese force. Japanese destroyers stayed around only long enough to send Hornet beneath the waves with torpedoes. Even though Nagumo had two operational carriers left against Kinkaid’s one, the Japanese had suffered severe losses of aircrews and were forced to give up the campaign. On land, the Henderson Field defenders had repulsed their attackers, and this would be the last major attempt by the Japanese to retake the field. In spite of the loss of Hornet the Americans had regained control of the sea around Guadalcanal. [15, pp.89-90] [9, p.255]

Among the American pilots, there was considerable unhappiness about the day’s fighter direction. They reported that, except for two pilots, they had never been vectored to engage the attacks on Enterprise before the Japanese started their dives. They also complained that, except for the Hornet FDO’s vector at start of battle, all direction had come from Enterprise even though the two carriers had been beyond visual range for most of the day. The Hornet fighter squadron CO reported that the Wildcats had been constantly vectored in and out in various directions and altitudes attempting to find enemy planes, and there had been a profusion of orders that pilots had great difficulty in understanding. Later reviews of the radio log verified this; in fact it was noted that the Enterprise FDO gave only three orders using standard fighter direction terms. While Enterprise was maneuvering to avoid bombs and torpedoes, Griffin had given relative bearings with respect to the wildly gyrating ship, that had no meaning to the pilots. Later analysis of Griffin’s log showed he had only rarely used relative bearings, and only when he had no other recourse. Hornet’s fighter squadron commander also felt that the FDO should have sent most of the CAP to 20,000 feet at the start of the engagement. He concluded that he did not think one FDO could effectively employ as many fighters as he had at his disposal, and that the Hornet’s FDO should have directed his carrier’s fighters. [11, p.24] [34, p.458]

CDR Griffin realized there had been a number of shortcomings in fighter direction and did a detailed analysis of the entire battle to determine what had gone wrong, and what could have been done better. Among other things, he realized that when accurate enemy altitude information is not available, a substantial portion of the CAP should be sent to 20,000 feet. He offered his analysis for inclusion in the Enterprise battle report but it was ignored. CDR Griffin returned to his Pacific Fleet Radar School in January 1943 where he worked the lessons learned from the Battle of Santa Cruz into his curriculum, to the benefit of future generations of fighter directors. Hornet FDO, LT Alan Fleming, was severely injured in the battle, but upon recovery rejoined the Pacific Fleet as senior fighter director in the new Lexington, where he would mentor numerous assistant fighter directors. Enterprise returned to Noumea where radar technicians from the repair ship Vestal gave the CXAM a thorough overhaul. They found that damaged waveguides had been one of the main culprits affecting its performance at Santa Cruz. [34, pp.458-459, p.463]

In his action report to the CNO, Admiral Nimitz wrote, “Our fighter direction was less effective than in previous actions. Enemy planes were not picked up until they were at close range, the radar screen was clogged by our own planes, and voice radio discipline was poor. Our fighter direction both in practice and in action against small groups has been good but fighter direction against a number of enemy groups with our own planes in the air is a problem not yet solved.” It was concluded that fighter direction during the first year of the war had not been very effective. In three out of four major carrier duels so far, the enemy had been able to sink one of our carriers. None of the action reports seemed to acknowledge that the Enterprise FDO was brand new to the ship and had never had a chance to work with the team before, that a number of experienced radar men and plotters had been removed from the ship before the battle, and radar performance on both carriers had been very poor. [11, p.24]

Agonizing Reappraisal

CAPT Hardison, skipper of Enterprise, in his Santa Cruz action report stated, “Fighter Direction having fallen short of expectations in two successive actions, a careful re-examination and analysis of the problem is required.” Re-examination was made at many levels with the following findings:

- Use of standard procedures and fighter direction vocabulary is essential.

- It is feasible to use radar information alone to send a large percentage of the CAP out twenty to thirty miles from fleet center.

- The problems in fighter direction are largely due to equipment and facility limitations.

- Most fighter direction mistakes have been due to the above limitations and the extreme pressures under which the FDOs work.

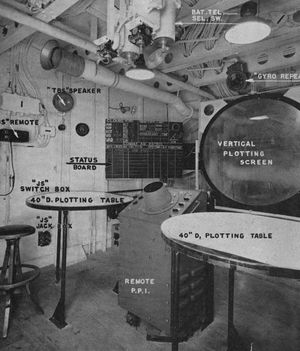

- The radar plotting rooms are far too small necessitating plotting all radar reports on one small chart, and can not accommodate the needed plotting and recording team.

- The radar plotting rooms are located where too many unwanted spectators can get in the way.

- The CXAM radar is capable of detecting targets at great distances but its display scope is difficult to interpret.

- A means of accurately determining target altitude is vitally needed.

- Though most aircraft now had IFF equipment, the sets had reliability problems, and more pilot indoctrination in its use was needed.

- The fighter direction radio circuit was unacceptably overcrowded.

- There is hesitation in using the medium frequency fighter direction radio circuits because of their long range and possibility of detection.

- The above problem restricted the ability to have frequent intercept practices that could have improved fighter direction effectiveness and radio discipline of both pilots and FDOs.

- The Japanese usually send fighter protection with their air strikes, and the Wildcats were at a distinct disadvantage in rate of climb compared with Zero fighters.

- If the FDO does not have a good raid altitude estimate, he should stack his CAP at differing altitudes, some quite high.

- The throat microphone of pilot’s oxygen masks needed improvement, and was detrimental to sending fighters to high altitude.

- None of the many critical studies and analyses questioned the concept of fighter control by a shipboard fighter director.

Admiral Nimitz, in November 1942, directed in Pacific Fleet Tactical Bulletin no. 4TB-42, that every Pacific Fleet combatant ship was to have a “Combat Operations Center” (COC) with radio equipment on the fighter and warning nets. It was also to have interior communications with the bridge, radar rooms, gunnery stations, and fire control stations. It was to be provided with tactical and strategic information, weather, and navigation data and a means of displaying such information. Subject to the orders of the Officer in Tactical Command, the COC was also to have control of the ship’s radars, and whenever the ship was a Fighter Director or Radar Guard Ship it was to transmit data on air targets in a standard format. Nimitz went on to direct that search radars were to be in operation at all times when there was a possibility of enemy contact. He noted, “Although the use of radar may possibly disclose our presence, the information to be gained from it, plus the warning of impending attack, will usually far outweigh the negative value of radar silence.” [11, pp.24-25] The equipment and capabilities to be embodied in the concept of the combat operations center were being well implemented in new-construction ships, especially in the new Essex Class carriers. However, in existing ships the fitting out of the COC was left up to the improvisation of ship’s company, and guidance from higher authority was mostly in terms of functions and capabilities. Aboard the battleship Mississippi, LTJG Edward C. Svendsen found himself suddenly “promoted” from Radar Officer to Combat Operations Center Officer. He could find almost no design guidance as to how the COC should be laid out or how it should be equipped, so he worked up his own design. Whenever the ship was in a repair facility or shipyard, Svendsen and his men scrounged equipment and material to continue building out the COC. [38]

In December the Chief of Naval Operations issued a Temporary Change to Cruising Instructions for Carrier Task Forces, incorporating fighter direction lessons learned in an expanded annex on Fighter Direction. It started out with the statement, ”Control of combat patrols by the Fighter Direction Officer must be absolute.” It went on to say that, against an incoming raid, the FDO must send out enough fighters to thwart it, and the intercept must be made at the maximum possible distance from task force center. Furthermore, the FDO was to keep reserve CAP over TF center, and that fighters should never chase a retreating raid. If raid altitude was not definitely known, the FDO was to stack his fighters, with most at the higher levels. To pilots, the CNO directed they must tell the FDO his range and bearing from TF center when leaving station on first vector, as well as weather status; and upon tallyho, he must send back raid size, altitude, and aircraft type. Pilots were to repeat back all orders. [11, p. 25]

A New Task Force Air Defense Organization

In the Change to Cruising Instructions, the CNO also abolished the position of Commander, Air. From now on, the Officer in Tactical Command (OTC) would be in charge of radar control and fighter direction. A carrier task force could be composed of just a few carriers or many. In a small task force, each carrier and its supporting ships might be designated as a task group, and in a large task force, a task group might be made up of a number of carriers and supporting ships. The carrier task force would be under the command of a flag officer flying his flag in one of the carriers, and each task group would be under the command of a task group commander, usually a flag officer aboard one of the task group carriers. If all carriers were together in a main body, the task force commander would be the OTC of all units present, but if a task group was on duty detached from the main body, the task group commander would usually be designated OTC of that group. If air operations were expected, the TG commander would usually be the senior aviation flag officer on one of the carriers, and if surface action was expected to predominate, the TG commander would usually be the senior battleship or cruiser flag officer until the engagement was over. The COC officer aboard a task force or task group flagship was also designated as TF or TG COC officer and reported directly to the Officer in Tactical Command. He also represented the OTCs authority to direct and coordinate the COCs of all the ships in his respective force of group. He might be called either the TF or TG COC officer or the TF or TG Fighter Director Officer depending on the preference of the OTC. As the war progressed, many OTCs would decide to keep a particular COC Officer or FDO on his staff as he moved from command to command. [11, p.25] [52, pp253-254]

Other components of the task force air defense organization were the Air Control Ships, Radar Guard Ships, and Picket Ships. Air control ships were designated as such by the group COC officer, and were responsible for controlling specific CAP assigned to them by the group COC officer. To use their facilities to best advantage, they were not normally also assigned radar guard duties. Usually, if a carrier had CAP airborne, the carrier’s COC officer had charge of that CAP, but intercept control for a particular raid would then be assigned to the air control ship having the best vantage point for intercept control. Several air control ships, working as a team, would be assigned in each task group. As a raid progressed, the TG COC officer might shift intercept control to a different air control ship having a more advantageous radar view of the situation. Radar guard ships were also designated by the group COC officer to search specific sectors, to do short, medium, or long range air searches, to do surface searches, or low flying coverage. Picket ships were usually destroyers or destroyer escort types, and were stationed on duty remote from the main body by task force or task group commanders. Their usual duty was to give advanced raid warnings, and to control the CAP assigned to them to intercept the raid. [52, pp.254-255]

The task force COC officer was to be responsible for coordinating COC operations throughout the task force, and he normally exercised his direction via the task group COC officers. He usually did not have control over any assigned aircraft or radars, but rather assigned CAPs and radar control to the task group COC officers. He would usually not have a direct part in conducting intercepts, but rather make sure others were assigned, well coordinated, and well informed of the overall tactical picture. He was also responsible for keeping the OTC updated on the tactical air situation. His specific duties would include the following:

- Decide the number of CAP to be put in the air, and the task groups that were to provide them.

- Assign each raid a number.

- Maintain the status of deck condition codes of all carriers.

- Keep an up to date summary of all air and surface units available to the OTC.

- Coordinate all task force night fighter activity.

- Keep track of enemy and friendly radar countermeasures activity and recommend to the OTC what counter and counter-countermeasures he should undertake.

- Prescribe the locations and duties of radar picket ships, and arrange for their CAP.

- Set the requirements for task force radio, radar, and IFF silence.

The task group COC officer had a much more hands-on job, charged with the direct air defense of the task group and the pulling together of all COC actions of the group. His charge was the task group as a whole, he was to get information from all COCs in the group, and direct immediate actions. His specific responsibilities included:

- Coordinate all group ship’s air and surface search radars, including ordering conditions of radar and IFF silence as directed by the OTC.

- Assign radar guard ships.

- Carry out the OTC’s orders to initiate jamming and deception.

- Assign communications radio frequencies.

- Pass to the group COCs and OTC information on all radar contacts, pilots reports, enemy message intercepts, and enemy radio/radar emissions.

- Specify the number and locations of CAPs.

- Direct which ship is to control an intercept and with which CAP, and direct reassignment of CAP to other ships as a raid progresses.

- Coordinate task group AA fire including setting guns free and guns tight conditions, and when necessary, assigning specific targets to specific ships.

- Direct what carriers are to have fighters in readiness and how many, and order launch of replacement fighters.

- Scramble fighters to intercept new raids, with the concurrence of the task group commander.

- Maintain status of all task group airborne fighters including their fuel and ammunition state.

- Maintain the status of all airborne strike, sweep, search, and attack aircraft in his group.

- On the direction of the task group commander, assign picket ships and their locations, scouting units, and linking communications ships.

- Set up the schedule of fighter launches, returns, and reliefs.

- Assign raid numbers to attackers approaching his group, if the force COC officer has not done so.

- Stay in constant touch with the force COC officer and with the COC officers of his group and insure that all information of value is passed to them.

Of the task group COC officer, the Aircraft Control Manual stated, “He must be prompt, decisive, and fully informed. He must know the capabilities of the radars and the aircraft in his own group, and he must be letter perfect in understanding both the broad outlines and the details of the operations plan.” It would appear that, in many respects, the job of the task group COC officer/FDO was more demanding than that of the task force COC officer. One can see that he and his team had to accurately handle a huge quantity of fast changing detail, and if they couldn’t, lives and ships could be lost. [52, pp.255-258]

It would be eight months before there would be another major carrier duel, and in the meantime, fighter direction would spread from the carriers to smaller ships, and beginning with the Guadalcanal landings, to radar/FDO teams ashore. We will review the effects of this change in the next chapter.