The Foundations of Mobile and Cellular Telephony

This article was initially published in Today's Engineer on August 2012

On 17 June 1946, a driver in St. Louis pulled out a handset from under his car’s dashboard, placed a phone call and made history. It was the first mobile telephone call, placed on a system inaugurated by Southwestern Bell, one of AT&T’s local operating companies.

A team including Alton Dickieson and D. Mitchell from AT&T’s research unit, Bell Labs, and H. I. Romnes from AT&T’s manufacturing subsidiary, Western Electric, had worked more than a decade to achieve this feat. By 1948, wireless telephone service was available in almost one hundred cities and highway corridors. Customers included utilities, truck fleet operators and reporters. But with only 5,000 customers making 30,000 weekly calls, it was far from commonplace.

This wireless network could handle only a small volume of calls. A single transmitter on a central tower provided a handful of channels for an entire metropolitan area. Between one and eight receiver towers handled the call return signals. At most, three subscribers could make calls at one time in any city using the single transmitter and the tiny amount of spectrum allocated by the Federal Communications Commission to this service. It was in effect a massive party line, where a tightly controlled number of subscribers had to listen first for someone else on the line, and, if finding the line free, signal an operator, who would place the call. During the call, the user depressed a button on the handset to talk and released it to listen. The equipment, of course employing vacuum tubes, weighed eighty pounds, filled much of a vehicle’s trunk and drew so much power that it would cause the headlights to dim. Service cost $15 per month, plus thirty to forty cents per local call, equivalent to $175 2012 dollars, plus $3.50 to $4.65 per call.

In 1965 an improved system, known as IMPS (for Improved Mobile Telephone Service), combined with a small increase in available spectrum, brought a few more channels and customer dialing, and eliminated the push-to-talk button in favor of full duplex capabilities. But capacity remained limited to the point that Bell System officials rationed the service to 40,000 subscribers, selected according to agreements with state regulatory agencies. For example, 2,000 subscribers in New York City shared just twelve channels, and typically waited thirty minutes to place a call. There was a long waiting list for would-be subscribers attesting to the demand for the service; a demand that could likely only be met by better technology.

Something better — cellular telephone service — had been conceived in 1947 by Donald H. Ring at Bell Labs, but the idea could not be put into practice. His concept included multiple low power transmitters and receivers spread throughout a region or highway in series of cells, with different frequencies used in adjacent cells but reused within a city (or along a highway), and a way to switch the calls to adjacent cells as a vehicle moved down the road. The technology to implement such a scheme did not yet exist and the spectrum needed was not available. AT&T had applied to the FCC for more spectrum as early as 1946 and again in 1958, but none was forthcoming until 1968, when the FCC asked AT&T for a proposal for using a significant swath of spectrum that had been allocated to UHF TV channels 70-83, but was underused. A team of young research engineers at Bell Labs, including future IEEE fellows Joel Engel and Richard Frenkiel, had begun working on advanced mobile telephony two years earlier, rediscovering Ring’s concept, and developing it as a network of hexagonal cells. With the availability of solid-state electronics and computers they were able to propose a working system. Bell Labs switching expert (and IEEE Fellow) Amos Joel contributed another other crucial piece — a system to automatically switch the call from one cell to another. In 1971 AT&T submitted its report to the FCC for an analog cellular telephone system to be operated by AT&T on spectrum to be allocated by the FCC.

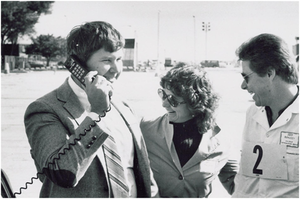

AT&T considered the system as a better way to provide telephone service to moving vehicles. Since all the vehicle equipment for the existing system was made for AT&T by Motorola, AT&T shared its work on the new system with the other company. Motorola, however, had another larger and more profitable business providing point-to-point private vehicle systems for Radio Common Carrier (RCC) uses like taxi dispatching. Motorola was afraid that a cellular system under AT&T control would mean the end of this business. So, Motorola did two things — it convinced their RCC customers to work with Motorola to argue before the FCC that the new spectrum and technology should not be the exclusive province of the telephone company, and it put a team to work on developing a hand-held cell phone, under the direction of company Vice President Marty Cooper. Cooper’s team succeeded, demonstrating a working prototype in April 1973. It weighed 45 ounces (1.28 kg) and its rechargeable battery was good for only around 30 minutes of calling, but it worked. His first call, made from a New York City street minutes before the scheduled public demonstration, went to his counterpart Engel at Bell Labs. The demonstration got the media’s and, more importantly, the FCC’s attention. Nonetheless, the FCC took eight years to decide what to do. While the FCC commissioners were deliberating, they authorized AT&T to demonstrate a working prototype commercial system in Chicago in 1978 and Motorola a system in Washington the following year.

Finally, in October 1981, the FCC announced that it would allocate two swaths of frequencies in the 800MHz range to cellular telephony, and would award two licenses in each market — one reserved for an incumbent wireline (i.e. telephone) company, and one for a non-wireline competitor. AT&T and its subsidiary Illinois Bell opened the first modern cellular system in Chicago in October 1983. A Motorola-designed system opened in Washington and Baltimore soon thereafter.The phones were expensive — a car phone cost $2500 and a portable phone $4000, not including airtime. With the breakup of the Bell System on 1 January 1984, all of the Bell System licenses passed to the newly divested regional telephone companies.

Cell phone service availability quickly spread throughout the country as the FCC awarded more and more local licenses in what proved to be an increasingly complicated process. Cell phone sales and subscriptions far exceeded all expectations; apparently almost no one anticipated that mobile telephony would become more than a niche service. One well known, but not unique study, done by the consulting firm McKinsey and Company for AT&T in 1983, predicted that there would be 900,000 subscribers in the U.S. by 2000; that number was reached in 1987. (The actual total in 2000 was 109,000,000.) With this rapid growth, the available spectrum quickly became crowded. This led to pressure for the FCC to authorize additional spectrum (a pressure that has never ended), which it did. It also led to research by several companies into more efficient spectrum use. This resulted in two distinct digital transmission systems, TDMA, introduced in 1989 and CDMA, introduced in 1995.