Oral-History:James F. Scott

About James (Jim) F. Scott

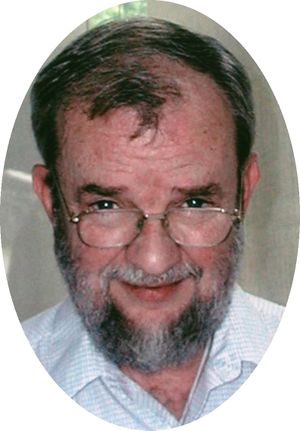

James F. Scott was born in New Jersey, USA, and educated at Harvard (B. A., physics 1963) and Ohio State University (Ph.D., physics 1966). After six years in the Quantum Electronics Research Department at Bell Labs he was appointed professor of physics at Univ. Colorado (Boulder), where he also served as Assistant Vice Chancellor for Research. He was Dean of Science and Professor of Physics for eight years in Australia (UNSW, Sydney, and RMIT, Melbourne), Professor of Ferroics in the Physics Department at Cambridge University, and since 2015 Professor of Chemistry and Physics at Univ. St. Andrews. His paper "Ferroelectric Memories" in Science (1989) is probably the most cited paper in electronic ceramics with 4000+ citations, and his textbook of the same title has been translated into Japanese and Chinese. He was elected a Fellow of the APS in 1974, and in 1997 won a Humboldt Prize and appointment as the SONY Corp. Chair of Science (Yokohama). He was awarded a Monkasho Prize in 2001 and in 2008 was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) and recipient of the MRS Medal (Materials Research Society). In 2011 he was elected to the Slovenian Academy of Sciences where earlier he had won the Jozef Stefan Gold Medal. In 2014 he won the Thomson-Reuters Citation Laureate prize, which describes itself as a predictor of Nobel Prizes in Physics, and in 2016 received the UNESCO medal for Contributions to Nanoscience and Nanotechnology. His work has been cited 50,000 times in scientific journals, with eight papers each cited more than 1,000 times and a Hirsch h-index of 100.

About the Interview

Jim Scott: An interview conducted by Roger Whatmore, Imperial College London. Conducted at Jim Scott’s home in St Monans, Fife, Scotland on Saturday 29th December 2018.

Interview #826 for the IEEE History Center, The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc.

Copyright Statement

This manuscript is being made available for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the IEEE History Center. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of IEEE History Center.

Request for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the IEEE History Center Oral History Program, IEEE History Center, 445 Hoes Lane, Piscataway, NJ 08854 USA or ieee-history@ieee.org. It should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user.

It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows:

Jim Scott, an oral history conducted in 2018 by Roger Whatmore, IEEE History Center, Piscataway, NJ, USA.

Foreword by Neil Mathur and Roger Whatmore

Jim Scott sadly passed away on April 6th 2020 in Cambridge, England aged 77, after a life that had broad and enduring impact in the field of ferroelectric materials and their applications. Jim was a very special person, who had a huge influence on many people in our field. Born 4 May 1942 in New Jersey to poor parents without secondary education, he studied at Harvard and worked at Bell Labs. During a long stint on the faculty at the University of Colorado, he integrated ferroelectrics with silicon, co-founding the Symetrix Corporation, and paving the way towards the commercial applications that we enjoy today. After many years in Australia, where he maintained his research output despite important managerial roles, in 1999 he was recruited as a Research Professor by Ekhard Salje in the Department of Earth Sciences in Cambridge. This later became a regular Professorship and Jim was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society while in the Department. It was only on reaching the standard age for retirement that the then Head of Department of Physics, Peter Littlewood, brought him to the Cavendish Laboratory as a Director of Research. In both Cambridge departments, he continued to make huge contributions to ferroelectrics, returning to multiferroics in Earth Sciences, working on quantum criticality at the Cavendish, and sometimes lamenting the fact that the world had forgotten his deep knowledge of Raman spectroscopy from Bell Labs. After retiring from Cambridge, Jim had yet more very productive years of paid employment in St. Andrews, alongside his former group member Finlay Morrison, before finally returning home to Cambridge in fading health at the start of 2020. Jim’s many great achievements include writing the classic book on ferroelectrics and making the shortlist for the Nobel prize. Jim did not tolerate nonsense and proved it in print by showing that electrical leakage could cause bananas to produce electrical hysteresis loops, just like supposedly ferroelectric materials. This was a great joke for him because BaNaNa was the well-known soubriquet for a ferroelectric tungsten bronze oxide (barium sodium niobate) that had been heavily studied for optical applications during his time at Bell Labs. Jim had – and will continue to have – a huge following amongst his former students and collaborators around the world, to whom he was both a great mentor and a great friend. To know him was to enjoy his creativity in both physics and storytelling, and he was so larger than life that we who are left cannot believe he is gone. From a personal point of view, he was a great friend to us both. He introduced us in 2004, permitting the three of us to work on electrocalorics, and our 2006 Science paper revitalized the subject and its applications potential. His love of the Russian academic literature and its transliterated author names were a particular bonus. NM was privileged to have good access to such a brilliant collaborator and friend across the road in Earth Science. RW was privileged to be able to conduct the interview transcribed below on a cold afternoon in late December 2018 at his house on the seafront in St. Monans in Fife, Scotland. He was made very welcome by Jim and his wife Galya, and remembers that experience with great affection.

Interview

INTERVIEWEE: Prof James (Jim) F. Scott

INTERVIEWER: Prof Roger W. Whatmore

DATE: 29th December 2018

PLACE: St Monans, Fife, Scotland

Earliest Days

Whatmore:

This is an interview for the IEEE Oral History record, and I'm delighted to be talking to Jim Scott here at his home, right by the quayside in the lovely fishing village of St Monans, on the northern shore of the mouth of the Firth of Forth in Fife, Scotland. Jim, the plan is to do an oral history of your experiences over your lifetime and what has led you to do what you have done. Can we start with your childhood: when and where you were born and your upbringing?

Scott:

OK. I was born in a very small village in New Jersey. The village has absolutely no charm. It’s not somewhere one would have nostalgia for. I never go back. It was dreadful – it’s still dreadful – it’s becoming more dreadful. It sits about ten miles from a large city called Camden, New Jersey. Camden used to be famous - in the Guinness Book of Records it was listed as the poorest city in the USA, as of 1980 you could still buy a detached four-bedroom house for £3,000.

Whatmore:

Wow!

Scott:

There is a good reason for that. It has a very high crime rate and it’s where the people who are too poor to live in the North part of Philadelphia, which is already dreadful, live across the river and commute into work from – that’s if they have a job, and most of them don’t.

Whatmore:

Right.

Scott:

So that was the community I was born into – I don’t want this to sound like something out of Dickens, because it wasn’t terrible – but I was born into a very poor, completely uneducated family. My father had been orphaned at four in a small coal mining village in West Virginia, and at thirteen went to work in the pits. That was even younger than it would have been here in Britain. When he was sixteen, he was big, so he lied about his age, joined the army and got out of the pits. My mother was the youngest in an Irish Catholic family of ten children and she was blinded in an automobile accident at the age of about thirteen when got a windshield through the face. This was before the days of safety glass windows in automobiles. So, eventually she recovered some vision, but not to normal levels. So, my parents never went to High School and I don’t know, but I suspect – I remember a conversation about this when I was a Professor at Cambridge – that I might have been the only FRS Professor of Physics in Britain whose parents didn’t attend High School.

Whatmore:

Wow. So, this was 1943 you were born?

Scott:

’42. May of ’42. In fact, it was interesting because when Pearl Harbour happened, my mother had to take a doctor’s letter into the Draft Board to show that she was pregnant with her second child. Unlike Britain, America didn’t draft men who had two children.

Whatmore:

Oh, right.

Scott:

So, being pregnant with me meant that my mother kept my father from going back into the War. That was very helpful, because he had previously done six years in the South Pacific and he would have been one of the first to go back there.

Whatmore:

Right.

Scott:

So, he didn’t go back into the army and I grew-up in the years immediately after the War, which were rather gentle and optimistic in the US. We didn’t have rationing, we didn’t have all the things that you were used to in Britain and it was, relatively a period of almost euphoria. These were the Eisenhower years, if you like ...

Whatmore:

The US had done well out of the war, really. The US had come out of the War ...

Scott:

We came out of the War with full employment, which was the main thing, and we didn’t have to rebuild cities that had been bombed to ashes and so-on. So, it was not a bad time to grow-up in the US, it’s just that in any period of time there are rich people and poor people and I was surrounded by poor people.

Education – School and College

Whatmore:

Where did you go to school?

Scott:

I went to school at the nearest State school, both for elementary school and high school. I would describe it as ‘relatively harmless’. There was not a lot of crime – there was nothing to steal – so I lived in a neighbourhood that was impoverished but not violent. To make things even more colourful, no-one ever bothered to lock their front doors because this was a Mafia neighbourhood and they were far more efficient about policing things than the local constabulary was.

Whatmore:

Right. So, what were your major influences at school?

Scott:

Well in a school like that you’re going to be influenced by one or two teachers. So, when I finished at High School, I thought I would probably major in English Literature, because I liked particularly my English teacher and I concentrated on reading everything ever written by Sinclair Lewis: Babbit, Arrowsmith, Dodsworth and so-on. Sinclair Lewis didn’t like ‘small-town US’. He won his Nobel Prize by sitting in his flat in Rome and writing about it. I shared his view that ‘small-town’ America is rather shallow and superficial and what I wanted most was to escape. So, I didn’t know anything about universities. I didn’t know whether I would major in Physics or English. So, I applied to Harvard because someone told me that was good. That was the only reason and I only applied to two schools – Harvard and our State university. Somewhat to my surprise, I won a full bursary to Harvard and in my first year I didn’t study any Physics.

Whatmore:

So, it was a general degree ...

Scott:

Just an Arts degree – Philosophy, History, English Lit. In the second year I took up Math, Chemistry and Physics and discovered that there were a lot of smart kids there.

Whatmore:

And what drew you into that?

Scott:

This was Sputnik era, so the Russians, they did it ...

Whatmore:

Right ... you saw it as being exciting ...

Scott:

Yes – the space effort was just gearing-up – people were becoming aware then.

Whatmore:

Were you aware of ... there must have been a lot of class differences ...

Scott:

Yes. I did not like Harvard. All of my friends were rich. They had all come from the most-expensive private schools, which in the US are Exeter and Andover – the equivalent of Eton and Harrow and suchlike and at best they were condescending.

Whatmore:

Right – that wouldn’t go down well ...

Scott:

Well, not for me. Some people would suck-up to that but some of us don’t.

Whatmore:

OK – so you were drawn into the Sciences in Harvard. I don’t know the American system that well, but you finished your first degree ...

Scott:

Yes, so Harvard – I don’t like Harvard at all, so I’ve nothing good to say about it, but what I will say was that the academic programme was beneath contempt. We never saw any Physics whatsoever in four years beyond 1899!

Whatmore:

Interesting ...

Scott:

We never saw any quantum theory ... no-one ever mentioned things like superconductivity or superfluid helium. We were doing four hundred boundary-value problems you could have done in 1875 ... over and over.

Whatmore:

So, this was the late ‘50’s?

Scott:

No, it was worse. It was 1963! Harvard didn’t believe that undergraduates should get the time of day. It was a fine place, probably, to be a PhD student but the professors didn’t meet office hours for undergraduates. They tended to be impolite, and if they were asked questions then they thought that, basically, we were an irritation.

Doctoral Studies

Whatmore:

So, you went straight from Harvard into a PhD course?

Scott:

Yes, that’s right. When I graduated from Harvard, I was engaged to marry a young woman who lived in Ohio and had one more year of university to go. She was a year younger than I. So, I went to Ohio State so I could enter my graduate, post-graduate programme while she finished her undergraduate degree. That worked unusually well, partly because I was, kind-of, a crazy workaholic. In post-graduate work in the US you take coursework and exams. So, I took fifteen hours a week of coursework and exams. I took the preliminary exams. I had to pass the language exams in both French and German and I took the PhD comprehensive exam, not on the thesis but on all the coursework. This is typical in the US. It’s five eight-hour exams – every day for a week. At that university you could pass at two levels. You could fail, you could pass at the Masters’ level, which meant that you had to do a separate Masters’ thesis, or if you did very well you could pass at the PhD level.

Whatmore:

And you could go straight on?

Scott:

So, I went straight through. I did what turned out to be, I think with hindsight to be a very good PhD thesis and I finished at the age of 23.

Whatmore:

Which is very unusual.

Scott:

Especially in the States. At that point I turned-down a post-doc with Carl Sagan at Harvard – which was good because he got fired the next month. Most people don’t know that he was actually dismissed.

Whatmore:

I certainly didn’t know that!

Scott:

He published a student’s thesis in the New York Times without their name on it.

Whatmore:

Oooo!

Scott:

He was a very nasty man!

Whatmore:

So, your PhD thesis was in Raman spectroscopy?

Scott:

No, I knew nothing about Raman spectroscopy and I never studied solid state physics.

Whatmore:

So, what was your PhD thesis title?

Scott:

My PhD thesis was an ultra-high-resolution study of gas-phase acetylene. I was a molecular spectroscopist.

Whatmore:

OK.

Scott:

However, my timing was perfect. I was considered a very good student at Ohio State. My thesis advisor was enormously supportive.

Whatmore:

That’s hugely important, isn’t it?

Scott:

He was a very nice, very religious Hindu and he was probably the biggest influence on my career. The other person who was also important was Harald Nielsen, who was the Head of the Department. Harald Nielsen had won various medals – he was originally from Denmark – in theoretical molecular spectroscopy, and he had Parkinson’s disease, so he was becoming less-able to teach and in my last year there he asked me to teach his graduate course. Now, this was clearly a violation of protocol. There were Assistant Professors who could have done that, and there were post-docs too, and as a PhD student, it shouldn’t have been me. But I was, of course, honoured, and that also made me feel smarter than I probably was. Then I went to Bell Labs.

Bell Labs

Whatmore:

How did you go to Bell Labs, was it through contacts, did you just apply or ...?

Scott:

No, it’s a rather odd thing that we could come back to later. Now, at age 75 I have never had a job in life that I applied for. I have always been recruited. Bell Labs sent a recruiter once a year to Ohio State and asked the Department Head himself: “Do you have any excellent students?”, and he, of course, since I was teaching his course, said: “Yes, Jim!”. So, I was brought to Bell Labs and I was given my choice of all the labs there – about 50 or 60 – and to their surprise I took a two-year post-doc doing Raman spectroscopy with lasers.

Whatmore:

Right, and that was the very early days of lasers, of course.

Scott:

Nobody else was doing it. I didn’t know about lasers or Raman spectroscopy, but I had done experimental optics, which was not common. It was not a popular choice before lasers. It was considered a kind-of backwater – you know, Fresnel lenses and Cornu spirals and stuff like that, that everybody hated! But, I took a two-year postdoc, instead of permanent position in one of the other groups, which had a stock-option, moving expenses and so-on, and considering I had a two-month-old baby and no money in the bank, that was probably a strange decision. They asked me at Bell Labs why I was doing it. I said: “Because I’m 23 and in two years I’ll be 25 and I’ll still be employable.” And within six months or eight months they converted my position to permanent because I’d published a couple of papers in Phys Rev and another six months later my boss quit and went to California and I inherited his lab.

Whatmore:

So, what year was that?

Scott:

’66.

Whatmore:

So, that would have been about the same time as ... did you come across Alastair Glass there?

Scott:

Of course. I did know Alastair. Alastair worked in a different department, but initially we were all in the same big building.

Whatmore:

And Gerry Burns – was he there as well at the same time.

Scott:

No, no, no – Gerry was the enemy. Gerry worked at IBM, and we weren’t even allowed to talk with them. He was not permitted to visit, even. It was really kind-of stupid but that’s the way it was.

Whatmore:

And other people, like ...

Scott:

Walter Merz. When we look back on those days, we forget how many extremely good people there were there!

Whatmore:

Bill Brinkmann would have been there?

Scott:

Brinkmann was briefly my boss! Kumar Patel. Paul Fleury and I were contemporaries.

Whatmore:

Mal Lines as well?

Scott:

Yes.

Whatmore:

So, these were all big names in ferroelectrics.

Scott:

Of course. It was a big centre, because the company thought, rightly or wrongly that it was going to produce devices, and they were right, but it was post Bell Labs and it wasn’t done there.

Whatmore:

Right, so to come back to your work – at that time you were looking at the Raman spectra of all sorts of crystalline materials?

Scott:

Right, now the advantage I had in taking a two-year post-doc, as opposed to the permanent position, was that I was told from the very first day: “You may do anything you wish, absolutely anything.”

Whatmore:

Wow!

Scott:

“And, at the end of the year, if it’s any good, we’ll give you a big raise. If it’s bad, we’ll send you home. In the meantime, no-one will ask when you come in, or what time or what you do. Have a good time!” How can you beat that?

Whatmore:

You can’t, can you, for someone with imagination and enthusiasm ...

Scott:

And, at that age ...

Whatmore:

So, did you have to build your own Raman system in those days?

Scott:

No, because I was a post-doc, I was working for Sergio Porto, and Sergio was a bit of a madman from Brazil, with a great flair for doing things – and a relatively thin knowledge of what he was doing. Nevertheless, he was very successful with that, but within a year of my arrival he left to be a professor in California, and I was allowed to take-over the lab. So, I didn’t have to build a lab. It wouldn’t have mattered anyway, because at the time, you couldn’t buy argon lasers – we built our own. You could not buy a double spectrometer – we built the first. And so, most of the stuff we had was home-made and if Sergio had taken it all to California, I could have had it all duplicated in 90 days.

Whatmore:

So, it was in-house-built equipment and you were working at the “nuts and bolts” end of science.

Scott:

And I had a very skilled sixty years old technician, with whom I got on like “father and son”. He was great.

Whatmore:

So, the materials you were looking at – looking back at your publications from those days – you’ve got molybdates, tungstates, aluminates ...

Scott:

Quartz.

Whatmore:

Yes, quartz.

Scott:

It sounds silly now, but people who did molecular spectroscopy were very good at understanding vibrations in materials, unless they were piezoelectric. And that complication hadn’t been unravelled, despite the fact that all the theory had been done by Rodney Loudon here in Britain in ‘63, and so I wanted to tackle something where all the anisotropies would be manifest at once, and quartz was a good paradigm. So, I had the advantage that the first three papers I did as this post-doc in the first ninety days have each been cited about, I don’t know, 400 times or something like that. And it’s not that they were so brilliant, it’s that they were first. You can only be first once! So, I had the rare privilege of being able to work on anything I wanted, with good equipment and one technician. And so, providing you don’t screw-up, you’re going to find something, even by accident.

Whatmore:

So, were you looking at the alpha-beta transition in quartz in those days?

Scott:

Yes.

Whatmore:

So that was the ferroelastic transition.

Scott:

Right, in fact, I was the one who explained the soft mode.

Whatmore:

Right.

Scott:

So, that was first and then strontium titanate. Some of these papers have been cited bizarre numbers of times! I have one that’s at 6,300 citations now.

Whatmore:

Wow!

Scott:

So, I’m not sure this stuff was brilliant, but it certainly got read. Again, I was always trying to do something that somebody else wasn’t. I didn’t ever intentionally “hop on a band wagon”. It was always just: “let’s try to do this ...”

Whatmore:

Which is good advice ...

Scott:

Yes, and no! The problem is that you have to work for an organisation which doesn’t penalise you if you fail.

Whatmore:

Right – and was that true in Bell Labs?

Scott:

No.

Whatmore:

(Laughter)

Scott:

What would happen is that you would have a boss like Kumar Patel, who would have ten PhD’s working for him, and he would say to each of the ten: “I want you to each do a very high-risk experiment – where the chances of any success at all are less than 50-50.” OK – so as a boss at the end of the year he has two or three that worked, and he looks fantastic, and seven guys have their careers wiped down the toilet, because nobody protected them for wasting a year or two and not succeeding. So, I would caution organisations who try to do this to make sure that you don’t penalise failure if you encourage risk. You can’t have it both ways.

Whatmore:

So, at that point you were interested in lattice vibrations and optical properties ...

Scott:

I wanted to ... most of the people in our group at Bell Labs were very interested in lasers, because they could see correctly that these were going to be used for communication. They wanted new lasers, better lasers, faster lasers, fibre-optics lasers ... I didn’t’ want to do that, at all. Remember, my PhD was in spectroscopy. I thought the laser is a really nice tool to look at things like semiconductor optics, or structural phase transitions, just as a spectroscopist and as far as I could tell, almost nobody else wanted to do that, and for good reason. That’s not the way to become vice-president of Bell Labs. You’re not going to make a device, at least not in the short term, and that was never my interest. I didn’t want to be vice-president of Bell Labs. I couldn’t think of anything I’d like to do less!

International Collaboration - Scotland

Whatmore:

So, at that time I noted that you also had international collaborations. You had some collaboration with Roger Cowley ...

Scott:

Well, that was a bit of an accident. Bell Labs did not permit – by law - international collaborations because everything you did was proprietary. It was owned by the telephone company. So, you can’t be working with somebody in England or somewhere else. However, Bell Labs had a very nice programme – once a year they would send someone like me on a sabbatical. Typically, half a year, or maybe even a full year, but at partial salary – a third salary or a half salary. I had not travelled anywhere in my life, having grown up in this bustling village of 3,000, and I thought it would be interesting to go, in particular to Edinburgh, because some of the best work was done, as you know, by Bill Cochran and Roger Cowley, who were both there. So, to my surprise the company sent me. They had never sent anybody with as few years’ experience as I had.

Whatmore:

That’s interesting ...

Scott:

But they did, so I spent the year in Drummond Street, on the old campus at Edinburgh. I wrote in a book I published later that my biggest surprise was that they thought certain materials were ferroelectric at room temperature, which in our lab were not. And the reason was that the entire physics facility at Edinburgh was unheated, and the laboratory was in the basement which was at ten degrees centigrade winter or summer, and it was not nice! So, I shared an office with Bill Cochran and I did publish one paper with Roger Cowley.

Whatmore:

How long did you spend there?

Scott:

Exactly twelve months.

Whatmore:

Twelve months - and when was that?

Scott:

Oh, gee – so I’d turned 29, so that would have been in 1970-71. Pretty early. I told my neighbours here that I’d lived in Edinburgh 45 years ago, and some of them are from Edinburgh. I said it was quite different then. They said: “No, no, no Edinburgh hasn’t changed in 45 years.”. I said: “Well I can tell you two things that are different. I didn’t know what a milk bottle was, and if you didn’t bring your milk in within five minutes flat of it being delivered, the blue-tits poke a hole through the top and drink all the cream.” So, that’s changed. And the other thing that’s changed is that the milk was delivered by horse. It was a long time ago! And, they were still delivering coal in waggons pulled by horses.

Whatmore:

So, you spent a year here in Scotland, and then you went back to Bell Labs?

Scott:

Yes.

Whatmore:

You were in Bell Labs for a total of six years?

Scott:

Yes, that’s right.

Boulder Colorado

Whatmore:

And then you went to Boulder?

Scott:

Yes, and again in Boulder – so, it’s another of these – you’ll see there’s a series of these where I didn’t apply for a job, I was recruited. I was the grand old age of 29 and they offered me a Full Chair. So, I said “Yes, of course!” And I had twenty rather pleasant years in Boulder, Colorado.

Whatmore:

So, I would say that now you are probably better-known for your work in ferroelectrics and ferroelectric memories, ferroelastics and ferroics. When did you move from being a lattice vibrations person into having an interest in ferroelectric materials?

Scott:

I don’t know that’s ever the way it went.

Whatmore:

OK, then how did it go?

Scott:

At Bell Labs, and in the first year or two at Colorado, I maintained two separate and, at the time completely unrelated, lines of research and you will see how these turned out to be extremely fortuitous later. By the way, starting at that time, and to the present, I have never had a large group. I have published a lot – 800 papers – but I’ve never had more than two students and two post-docs at any time. The biggest group I ever had in my life was four people. It’s not about building an empire. We have a guy here in my building in St Andrews who has 54 people working for him. If you’re going to do that, you might as well be a Dean. So, I was always intimately involved in the work, running data or doing something similar, and that was the case there in Colorado. So, it was very handy because I could put one student and one post-doc on semiconductor scattering – plasmons and so-on, and another student and a post-doc on some phase transition, and that’s what I did. Now, to fast-forward, it turns out that all interesting ferroelectric oxides are semiconductors. Lead titanate has a smaller band-gap than gallium nitride does. These are semiconductors. They’re a little more complicated than silicon – too bad! But they’re semiconductors. So, you see I had twenty years of semiconductor optics and twenty years of ferroelectrics, and nobody else did. In fact, it’s bad luck for some of the people in Russia – I won’t name names here – but in the typical Russian curriculum, which was the same at every university in all the Soviet Union, in one particular year you could do semiconductors or ferroelectrics, but not both. So, the best of the ferroelectrics people in Russia, on average, know nothing whatsoever about semiconductors, and when they started making thin films and worrying about Schottky barriers and so-on, they made horrific qualitative mistakes that even I could fix! This made me relatively famous and severely disliked.

Whatmore:

(Laughing) Why is that?

Scott:

Well if you’re a pompous Russian theoretician who believes you speak only with God, having some American experimentalist correct your work is a bit awkward. So, that happened - a lot!

Whatmore:

So, you’re in Colorado – this is the early seventies, yes?

Scott:

Yeah.

Whatmore:

You carry on there – you spend some time in Moscow – when was that?

Scott:

Oh, not until much later.

Whatmore:

So, that was much later?

Scott:

Oh, 1980’s.

Whatmore:

Can you tell us something about the 1970’s for you?

Scott:

I learned how to teach. One of my great treasures in life is a plaque that hangs in the Physics Department, where I was selected as the outstanding teacher of the year, and this was selected by a secret vote of the students, not a political vote by the other faculty. I liked that. I taught thermodynamics. I love thermodynamics! The students were terrified about thermodynamics, and of course it’s not actually awful at all, it’s actually quite interesting. I learned how to teach. I became quite a good teacher.

Applications of Physics

Whatmore:

So, you’d spent some time in industry, in Bell Labs. Bell Labs was well known for pursuing all sorts of far-reaching research, but ultimately they were looking towards applications. As you pointed-out about lasers – they were looking at the applications of the science. They were looking at how one could use things. Is that something that remained with you?

Scott:

Yes and no. Bell Labs was so compartmentalised that we were actually discouraged from working with the device groups.

Whatmore:

Oh, really!?

Scott:

The numbers go, in order of descent from God. I was in area 1111 and by the time you got to area 5555 you were growing quartz crystals in Merrimac Valley.

Whatmore:

Right ...

Scott:

So, I was with the angels up there (in Bell Labs), there were people like, well, Nobel Prize winners floating around in the theory groups.

Whatmore:

So, you didn’t perceive a strong applications drive for what you were doing?

Scott:

Almost the opposite. In fact, there was a kind-of punishment. I’ll give you an example in our group: Bill Selfast, who was a very fine laser physicist from Utah and invented the helium cadmium laser - a UV laser, but it’s very cheap to make, like helium neon. So, what happened to him? He was offered a position to become a head of a department in the extreme device area, to stop this. I mean, it doesn’t fit-in with the basic research group that he’s in, you see. So, Bell Labs was a wonderful place, and it’s a great tragedy that it’s gone, but it’s the size and style of the US Army or the US Post Office. We had fourteen thousand people just in the New Jersey locations, so it’s going to be cumbersome to manage, not like running things nowadays. I mean, to give you an example. Compare it with a company like Google. You got ten days’ vacation a year, and if you wanted to go some-place like Europe, where you really need three weeks, you couldn’t save one week ‘til next year. If they’re not used, you lose them. You didn’t get any retirement vested until after ten or fifteen years. I left after six years, so that’s gone. It was a very old-fashioned company, and many things about it are embarrassing historically. So, Bell Labs didn’t hire any Jewish scientists until 1946, because their president was some Catholic anti-Semite who didn’t think that was a good idea. They were located at that time in Manhattan, and he said to a Congressional hearing, that there were no Jewish scientists in New York! So, they were required by Harry Truman to start hiring Jewish scientists or lose the entire Nike missile project. 1952, six years later, they were forced to hire their first Asians and until the time I left, which was ’81, they would hire about equal numbers of men and women at the BSc level, and the men would go into things like plant safety and occupational health and safety and waste disposal, and in ten years be making fifty thousand dollars a year, and the women would all be turned into software operators. Even worse, each of us PhD scientists had one technician working with us in our labs – there were dark labs with lasers in them. Women weren’t permitted to do that because the proximity of having a young woman in your lab with the lights out was considered to be bad! This was a telephone company that didn’t permit men and women to sit next to each other at switchboards until 1940. So, the company was still rooted deep in the 1890’s or something and occasionally that would be an irritation.

Whatmore:

So, you were at Colorado how long?

Scott:

Exactly twenty years.

Whatmore:

Twenty years, from 1971-ish to ..?

Scott:

‘91.

International Collaborations - Oxford

Whatmore:

’91. So, that period overlaps with several things that went on in your life. You spent some time in Oxford?

Scott:

Yes.

Whatmore:

Would you like to tell us something about that?

Scott:

Yes. I spent twelve months with Bill Hayes in Oxford, I guess it would have been ’71 to ’72. That was rather pleasant, partly because I learned to play cricket. I already knew how to play snooker, which is pretty unusual for an American, and I used that secret ability to hustle some of my friends! “Oh, what an interesting game – it’s like pool but you have all those red balls.”

Whatmore:

(Laughter)

Scott:

I particularly liked talking with Gillian Gehring. Gillian was there before she got, quote, the Chair of Experimental Physics at Sheffield, which was bizarre because she’d never done an experiment in her life, but I understand how these things work. I’ve been on search committees and, if you don’t get what you like you redefine the parameters a little bit. Gillian is a smart lady and she was very helpful. I liked talking to her about things, and at the time she and I were two among relatively few people who were interested in what we would now call multiferroics. At the time, I would say Hans Schmidt was famous for this. He did wonderful work, but I had done a lot of work in the 1970’s on, particularly, barium manganese fluoride, until my NSF renewal proposal got a very strange decision. I know who refereed it – they secretly told me it was from Eric Cross – and it says: “There is no conceivable interest or use in multiferroic materials and therefore you should only fund this if Professor Scott explicitly removes that entire section of his three-year proposal.” and they made me do it, so I got out of multiferroics in 1975 because Penn State thought this was useless. This happens again later with the ferroelectric memories.

Whatmore:

Right ...

Ferroelectric Memories

Scott:

We wrote a proposal – we were probably the only group in the US that Jane Alexander didn’t fund with a big DoE grant for work on ferroelectric memories, and that didn’t happen because, as she said – she didn’t identify the person – she said: “You have an extremely negative referee report from the largest ferroelectrics group in the US, from the person who is best-known in ferroelectrics in the country and he says: ‘There will never be any application for ferroelectric thin films’.” So, we got no money and we had to fund it privately.

Whatmore:

Right! So, let’s talk about ferroelectric memories then – we’re now up to that point in your career. What drew you into ferroelectric memories?

Scott:

It was a complete accident. I got a ‘phone call from George Taylor, who was in Perth Australia at the time, rather than Princeton, and he said: “Jim, congratulations! I understand you have a beautiful new Russian wife.” I said: ”Yes, that’s true, but that’s not why you called.” He said: “There is a strange young Brazilian, aged twenty-nine, a new Assistant Lecturer at the branch campus of the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs. The campus has a PhD programme in only one subject: Electrical Engineering and he is trying to make ferroelectric thin film memories. He’s never seen a ferroelectric – he doesn’t know how to spell ‘ferroelectric’. There are no double letters in Portuguese. He has found a book by Tomaspolshkii. It’s in Russian. It’s never been translated. We need somebody who can translate the entire 500-page book in a month.” I said: “Well, together with my wife, we could do this. She’ll put it into reasonable English and I’ll fix all the technical parts. So, every three days I would deliver a chapter of this stupid-assed book – ninety miles each way to Colorado Springs – and the book turns out to be absolutely useless. As my wife said: “This must have been written by an engineer who came through a polytechnic in a village. Even the Russian is wretched!” So, every time I would deliver a chapter, Carlos with ask me some technical questions.

Whatmore:

This was Carlos Paz De Araujo??

Scott:

So, he would ask me some questions about ferroelectrics and I would answer them, and then he would want written answers and he had a lot of private backing from Australia – Ramtron – and they said: “We will pay you consulting fees.”

Whatmore:

Was this Gavin Tulloch in Australia?

Scott:

It was Ross Lyndon-James who was a self-made millionaire with no education. To tell you about Ross Lyndon-James - for a while he was selling airplanes. He does not have a license, he does not know how to fly. He had a customer hot to buy one of these ‘planes. He said: “Well let’s get in a take it up.” He got in and took it off and flew it around and landed it! He’s a very interesting man – and very rich. Anyway, so they began paying me a consulting salary. I’d deliver something and they’d give me £100 or something like that – it was hardly worth a 180-mile drive. Any rate, after six months Ross said: “It would save us a lot of trouble and paperwork if we put you on a stipend instead of paying you on invoices”. I said: “That’s fine. It doesn’t matter to me how it gets done.” Except, it turns out to be five-to-ten times as much, which they didn’t tell me. Then later, they made me Chairman of their technical board of directors, and they gave me, I don’t know, £50,000-worth of stock, or something like that. So, I became associated with them in that way, only for translating a very bad book. In fact, the book was so bad that in the end George Taylor, his company wouldn’t publish it. They tried to give it away to somebody else to publish it and they had other publishers reject it, one of whom wrote the wonderful comment that – this was from a Russian reviewer – wrote that: “The translated version is enormously better than the original! Who wrote this?” But, the final offer was that they would publish it only if I wrote five up-to-date chapters. Well, I might as well write my own book! Meanwhile, I got a letter from the original author who said: “I don’t want you co-authoring a version of my book.”. I wrote back and said: “Fair enough, I wouldn’t touch it with a barge pole!”. His work was 1950’s “shake and bake” ... powders etc. It wasn’t useful.

Whatmore:

So, you’re involved with Ramtron, and you’re Chair of their Technical Board. At what point were they then? Were they close to commercialization?

Scott:

Well, they thought so, but they had a problem.

Whatmore:

Did they start with potassium nitrate?

Scott:

Yes, so they had a point where various internal things happened. So, they started with potassium nitrate and they let Carlos and Larry work only on that. They were never permitted to touch the PZT. That was given to me. I was offered a position, which I probably should have taken, as a short-term President of Ramtron because it would have paid an enormous amount of money. But, I just thought I don’t actually want to be a rich businessman – I like being a professor – so after a couple of months they hired somebody else, but they treated me fine. They were, I would say in general, it’s not that they were naive – they weren’t – but this was at a time – you have to put yourself back into the ‘80’s – when you could make $50 million in six months with a software company. You can’t do that with a hardware company. The lead-time is ten years!

Whatmore:

Absolutely!

Scott:

Maybe more. So, now it’s all reached fruition, these are stand-alone companies in the Far East - £100M per year. Every train ticket, you know – all this. All my patents are all gone. I don’t get any money from that.

Whatmore:

So, to get back to the history ...

Scott:

What happened – Carlos and I were working for Ramtron. Ramtron is 60% Australian owned. It is not, therefore, a US-owned company. Therefore, it’s ineligible for any Federal funding.

Whatmore:

Ah – so you can’t get SBRI or anything like that ...

Scott:

So, I went to the boss and said: “Look, would you let us split-off our little part, just Carlos and Larry and me as a smaller company which is mostly-owned by Ramtron. We’ll call it Symetrix – one ‘m’ – no double letters in Portuguese - and I will then write some proposals for SBIR’s.” He said: “Fine. What’s to lose?”. So, I wrote five proposals. The percentage of getting them funded then was five or ten percent. All five got funded! So, in the first month I had five times $50,000 – that’s already quite a bit. It’s only for six months. These are feasibility studies. At the end of six months, you can take an SBIR to Phase 2. That requires an industrial partner, but oddly-enough the partner need not be American. At the end of six months I had Japanese partners for all five, and we suddenly had five times $500,000, so we had two point five million dollars in the bank, which can be used for anything except profits – any chargeable direct charge. So, we had a company!

Whatmore:

That’s amazing!

Scott:

And we had the first working product ...

Whatmore:

That was using PZT or ...?

Scott:

That’s a good question ... what was the first project? The first project was probably potassium nitrate, which by the way is not a bad material if you look at all its qualities. I remember the first day of sale – I had a sixteen bit memory – not kilobits, bits!

Whatmore:

Right ...

Scott:

So, we had a guy from the air force come in and I gave him this chip and I said: “I’m going to have you put this in the PC in a minute and I want you to write your mother’s name in it.” And, fortunately his mother’s name was Marie or something, and not Antoinette! So, he wrote that in, and we showed him everything we were doing and baking and how it worked, and at the end of the day I said: “Before you leave, I want you to read your mother’s name.” He put the chip in the PC, and it worked. I said: “That’s a non-volatile ferroelectric memory, and we can scale that from 16 bits to 16 kilobits in eight or ten months”, and he said: “You have the money, sir!”

Whatmore:

Fantastic!

Scott:

So, typically what would happen is, I would drive from Boulder down to Colorado Springs for one full day per week. That was all I was allowed as part of my university duties and my university was not very sympathetic toward this, despite the fact that we were located inside the university. We rented labs and space from them, and it’s the same university and we had at Boulder at that given time maybe twenty people who would spend a day a week at the Med School, and that was considered great. Mine was considered not great, and I asked the Dean why. He said: “Because you’re earning a salary from it.”

Whatmore:

Rrrright ...???

Scott:

You’re being paid some kind of consulting fee. So, I pointed out to him that for the first two years of doing this, I hadn’t even been reimbursed for petrol! So, in the end what happened was, at that point we had quite a few things we wanted to file patents on. In fact, we had so many that it turned out to be cheaper for us to contract with a patent attorney for months of his time, rather than per item. We then very diligently went to the university and said: “We are professors, we work for you, we understand that you have a right to patents and we’d like to negotiate a deal for them.” Like most universities, they have some high-priced, but fundamentally stupid, person in charge of intellectual property, and he said – the conversation went something like this: “Let me get this straight. You’ve never made a product, nor sold a product, nor do you have any contracts to do so?” “Yes.” “You have a device which might work only at low temperatures?” “Yes.” “And it might wear out in a week?” “Yes.” “What do you think that’s worth?” And I said: “As little as possible. We’re trying to sell you your part.” So, he said: “The university will take, as payment in full, five percent of your new start-up company.” Five percent of a start-up company is worth, essentially, zero!

Whatmore:

Right.

Scott:

And I said: “OK, but we want something in addition. We’re going to make additional inventions in this area, and we want to buy you out in advance from that – just on this topic.” And he said: “Fine – ten percent of your start-up.” So, we went away with this. Fast-forward again to a couple of years later, we walked in and paid them, I think, two hundred thousand dollars for their part and he was a happy man. He can show this as a big win. Not only that, instead of getting the criticism I was getting from my Department Head and Dean, the University President went to the State Legislature and said: “This is what modern physicists should be doing – creating environmentally clean, high-paying jobs, and by the way, gentlemen, all this money came from Japan!” You see, so you go from being bad-guy to good-guy and basically it was a success.

Whatmore:

Right, so that was how Symetrix got started?

Scott:

So that was how Symetrix got started, but in the meanwhile, Ramtron got a new President and he decided that we didn’t all work for him – that we were competitors. So, I tried to explain to him the history, and why we’d done this, the fact that Ramtron was still mostly Australian owned and couldn’t get an SBIR, because it didn’t meet the requirements, but he didn’t know what we were talking about. So, we went our separate ways.

Whatmore:

So, you were working with potassium nitrate as a material, and then you were looking at the fatigue issues to do with PZT, presumably, or they were well-known.

Scott:

The problem with potassium nitrate, of course, is that it dissolves in water, but otherwise it has one fantastic property, which is a ratio. To make a ferroelectric memory, you want something that has a very large polarization, and a very small dielectric constant. It’s the only stuff I know that does. Nothing else does that. Because, if you have a large dielectric constant, then the non-switching signal as big as the switching signal. So, PZT is not ideal. So, we knew that. At the time we began working on PZT it was our own idea and it wasn’t mine. We just thought it met most of the requirements, but it became obvious pretty quickly that it fatigued. Now, this was, I think, entirely my idea. My belief was that the problem was due entirely to oxygen and oxygen vacancies. I felt that if we could replace the oxygens that got taken off the surface of the PZT by using an oxide electrode then the problem would disappear, and of course, it did. So that was one thing. And then the other thing we did that was related to that was that we used SBT. And there, as you probably know from the structure, there are certainly oxygen layers but the ones that give off the oxygen most-readily are the Bi2O2 planes that don’t affect the ferroelectricity. So, you lose oxygens, but it doesn’t screw-up the switching.

Whatmore:

So, is that what led you to look at the Aurivillius ferroelectrics?

Scott:

Yes, that was my idea and I think that was rather clever.

Whatmore:

Right, and that worked.

Scott:

Yes, that worked – that was the main thing. So, at that point we had product, but we could also see that this was going to require a very big partner. So, the partner we had was Matsushita Electric Company, and then we got into all kinds of Japanese politics. I was hired – from Australia – to be Sony Professor in the Sony Corporation in Yokohama for three months.

Whatmore:

So, at this point were you still in Colorado, or had you moved?

Scott:

No, I had moved to Australia, and Sony wanted to make SBT memories. So, they brought me in there. It’s a very distinguished position. Noel Clark had had the same position in the preceding year. And I was to help them make their device. It was to be a sixteen megabit ferroelectric RAM. I told them – I got to speak directly to the Vice-President of Sony a couple of times – that this was a “bridge too far” – they should make a sixteen kilobit memory. They said: “Well, our corporate history is leapfrogging over the competitors.” I said: “Well, I think it’s too ambitious.” Eventually they succeeded, but that’s very recent – another fifteen years downstream.

Whatmore:

So, what led you to move from Colorado to Australia – that’s quite a big jump!

Scott:

Don’t have two wives in the same neighbourhood! It was entirely personal.

Whatmore:

OK. So, it was a personal reason to move.

Scott:

Fortunately, I had not met Galya until after the divorce. So, she has nothing to do with this history, or everybody would have blamed her. I assure you, sometimes they try anyway!

Moscow

Whatmore:

We haven’t covered your period in Moscow. Should we rewind a little bit?

Scott:

Yes, let’s back-up to Moscow.

Whatmore:

When was that – late ‘70’s, early ‘80’s – something like that?

Scott:

It was October of ’81 and I’d just gotten divorced, so I wasn’t in a good mood and I didn’t particularly want another trip.

Whatmore:

But, you were drawn to Moscow for technical reasons. Obviously, you went for the science.

Scott:

Yes, I have been invited by the Soviet Academy of Sciences on, well – looking back now – ten occasions to give a series of lectures, including two before this time. So, I went, and I was not in a good mood. The only thing I’m sure of in life is that I’m never, ever going to get married again! Ok, so I walk in and on the very first day I bump into Galya, literally on the stairway as I’m getting my coat off, and I thought well, this is bad! Now, she’s the best English translator in the whole group and she works directly for Kapitza. So, she’s given two tickets for the Bolshoi Ballet, or a concert or something, every night for twenty-one days, and she’s told: “This poor Professor Scott has a very active scientific programme, but he has no social life. He’s going to be sitting in his hotel every night for three weeks and he doesn’t even have a TV. Would you please take him to the ballet?” So, she did this. Now, at the time, Galya was married but it was coming apart, although I didn’t have any knowledge of this at the time. I know two things: one, she is married and two she was doing this because she was told to, so ...

Whatmore:

It was a professional relationship ...

Scott:

There was no romance. Well, that’s not perfectly accurate. Let’s say that this was the most Victorian romance since 1893! I didn’t touch her, and everything went wrong. I had a car and driver. So one night the car and driver took us to the theatre which was fifteen miles across the other side of Moscow and he said, as he must: “Should I wait for you here” ... three hours until it’s over ... “and then take you home?” and she said: “No, just go home to your family and we can get a taxi or something.” And as he disappeared into the distance, she realized she had taken me to the wrong side of Moscow, to the wrong theatre, about thirty miles from where we should be, and the show was starting in five minutes!

Whatmore:

Oh, no!

Scott:

I said, well look, there’s a cafe here. Let’s get a couple of pieces of pie and some tea and we’ll just chat. It was great – it was the best evening of the whole trip. So, when I got back to Colorado, I’m about to leave on a year’s sabbatical – Brazil, England, Switzerland with Alex Mueller – and I thought: “I must write this woman a letter” and so I wrote her a letter which said: “Dear Galya, I want to complain that you have completely screwed-up my life. Before I went to Moscow, I was a fairly-happy, recent bachelor going-out with all the women in this university town., and having been married since I was about twenty, it’s very exciting. And you’ve spoiled that. I shouldn’t write to you at all. I understand that you are married, and you were just doing your job, and all that, but it would be poetically an injustice not to tell you what a big effect you have had on me.” So, I wrote that and sent it. Then I sent five more letters. She never answered any of these. Then I went to Brazil and then I went to England, and then I went to Switzerland. Nobody met my train or plane in Switzerland and I had to get through three feet of snow, find the village where I was living, find the key under my mat, under the snow, and let myself into my rented apartment, near IBM – and there I found her letters! They’d all been forwarded from Colorado, and Brazil, and England and one of them says: “I was very touched with your letters. Perhaps it would interest you to know that I’m getting divorced this month.”

Whatmore:

Right.

Scott:

So, I picked-up the ‘phone and called and proposed, and she said: “No, you can’t propose on the telephone. It’s not the way it’s done. You get yourself back here to Russia and we’ll discuss it.” So, the next day, instead of going to work the first day, I went down to the government office and got my work-permit, which you need in Switzerland, and then with this still warm in my hand I went to the Aeroflot office and said: “I would like to book a week’s vacation in Moscow.” They said: “We have one going this next week, but you can’t go. You have to be a Swiss citizen and the other six people going are all little old ladies in their seventies.” I said: “Fine. I’m a Swiss resident. Here’s my work permit.” They said: “OK. Fine. You’re on. Tuesday at nine!” So, I flew out and proposed and this time she said: “Yes.” I mean it’s all science-fiction stuff!

Whatmore:

It’s fantastic!

Scott:

Then, I thought: “It’s all just like any other country, you just get a marriage license and get married.” But – I’ll save all this for another day – it’s months of agony. There are thirty-seven steps that have to be done in sequence. Such as going to the telephone company and showing that the telephone, which is still in your ex-husband’s name, doesn’t have any money due on it, and that you don’t have tuberculosis, and that you’ve never been a mental patient, or a prostitute ... how would you prove that you’re not a prostitute?! So, Galya’s very smart. She went to a police station and got a document to prove that she’d never been arrested for anything. So, we got married. I was then arrested and taken physically to the airport and deported without her.

Whatmore:

Really! Wow!

Scott:

The day of the wedding.

Whatmore:

Immediately after the wedding!

Scott:

Well, it was supposed to be immediately after the wedding, but I got a lawyer and he said that technically I had “until noon tomorrow”. So, “noon tomorrow” I was on a plane to Bulgaria.

Whatmore:

Ouch!

Scott:

Well, things get worse, but that’s for another day. This is not what you’re here for.

Whatmore:

So, that trip to Moscow was a very fateful one for you?

Scott:

Yes, because it changed our whole lives. We’ve been happily married now for a very long time.

Whatmore:

That’s fantastic. So, you were in Australia for how long?

Australia

Scott:

Eight years.

Whatmore:

You were Dean there?

Scott:

Yes, I was Dean originally at RMIT and I was the first Dean literally from the day it went from being a polytechnic to granting PhD’s in fourteen departments, all mine. I’m Dean of Science. That was not nice! My entire staff – it was a good polytechnic, very big – my entire staff were guys who were around fifty-five – been teaching for thirty years, doing a good job – never published anything, including their thesis. I have to put-in a PhD programme in twelve months. We don’t have laboratories or even a big library. Even worse, it’s not that they’re all trying to figure-out how to do this and help me, and we might have different strategies. They’re all against this. They don’t want this happening.

Whatmore:

O, dear! Hmmm.

Scott:

This isn’t going to help them. They can’t do that. So, I’m trying to explain: “Please do not shoot the messenger. This is a decision from Canberra, not me, and they brought me in intentionally because I’m an American and I don’t know any of you. So, I don’t care if you’re a nice person, a bad person or what. What I care about is that you’re going to help me get this done or I’m going to fire you, or you’re going to get early retirement. You know this old cliché about how Deans work for you? That’s false. You work for me. You do exactly what I tell you and we’ll get along fine. Otherwise, go home!” I barely escaped assassination.

Whatmore:

But, did you get the programme through?

Scott:

Yes.

Whatmore:

Well, there you go!

Scott:

Well no. That would be your vote or my vote – it’s not everybody’s vote!

Whatmore:

But that must have been quite a wrench for you. You’d been steeped in research all your career and all of a sudden, you’re thrown into this completely different environment ...

Scott:

Well, I thought I’m safe. So, halfway through this I get hired as the Dean of the best university in Australia, the University of New South Wales in Sydney, which at the time was ranked as number one. And I thought: “They’re not going to have this problem,” – and they didn’t. The first month I found that the only woman Professor of Physics had stolen three hundred thousand dollars from her research account, built a house in the mountains for herself and bought a new car. So, what did I do? Well, I’d been through a Dean training school, and I know what I can do legally. So, I called the Federal police and I said: “I want to report a case of felony grand of theft of Federal funds.” For which, my Vice-Chancellor, who was six feet six and three hundred pounds, and used to be a prop-forward on his rugby team, said he was going to kill me! He said: “We handle these things internally. You’re going to bring the university into disrepute.” I said: “No sir, I’m going to get a whole bunch of people arrested, and if that includes you, I don’t give a f**k, I’ll be gone. I’m not going to grow old here.”

Whatmore:

So, what happened?

Scott:

He’s gone. I’m gone. In fact, it was really funny because it was so prophetic. What he said was: “The problem with you Jim is that you’re an elitist.” I said: “Oh, thank you!” He said: “Oh no – that’s a very bad word in Australia.”

Whatmore:

Unless it’s cricket!

Cambridge

Scott:

Yes, or swimming. He said: “You ought to be at a place like Cambridge.” Isn’t that funny because a year later, I was at Cambridge!

Whatmore:

And, was it Ekhard (Salje) who attracted you there?

Scott:

Yes, it’s one more job that I didn’t apply for. I’m sitting there in my Dean’s office, feeling absolutely pissed-off for stuff like this and Ekhard, whom I’d only met once, on a boat at a conference in Nantes, called me and said: “Jim, this is Ekhard” – fortunately there is only one Ekhard in the world – I said: “Oh, hi, how are you doing? How can I help you?” and he said: “Would you like a Chair at Cambridge?” Those were his first words. I said: “Yeah, I don’t know any physicist who wouldn’t.” It’s like being named Pope of something! He said: “I take that as a ‘Yes’”. I said: “Take what as a ‘yes’?” He said: “ I’m offering you a Chair at Cambridge.” I said: “Ekhard, I don’t know who you are, but you can’t actually do that. I know how these things work. I’ve been a Dean for a while. You have to get permission to have an opening. You then have to advertise the opening. You get two hundred letters of reference. You have a committee screw around with them for six months. Then you will invite five people, all at once.” That’s in Britain. In the US, of course, you would never, ever do that. You have to come one at a time – it’s as if you’re looking for a bride, or something like that. “And then you pick one.” He says: “No, you don’t have to do that.” And then he says: “Every university in the world technically has the right to hire by invitation.” I said: “Yeah, but you would do that with somebody like a Nobel prize-winner. So, if you want Tony Leggett at Illinois with his Nobel prize to come back to England for the last part of his life, you’re not going to ask him for five letters of reference and his transcript. But, I don’t have a Nobel prize.” He says: “Shhh. We’ve told the people here that you’re really pretty good. So, do you want this job or not?” I said: “How long to I have to decide?” He said: “You’re costing me about eight dollars a minute!” I said: “OK, yes!” Then I thought: “How am I going to explain this to Galya? Here she has a house she loves, on the water on the South Pacific on Sydney Harbour and she’s a serious swimmer.” Well, you know Galya a little bit, so I went home and said: “I accepted a job at Cambridge today.” And she said: “That’ll be fine. Tell me when to pack.” Kapitza loved Cambridge, and oddly enough, we live on the same street he did, we know his granddaughter extremely well, we’ve been in his house. Masha, his granddaughter, is a charming woman. She’s there a lot from Moscow. “Well,” I said, “you know what an American wife would have said if I came home and said I’d just accepted a job in Cambridge?” She would have said: “I’ll send you a Christmas card”. You’re not going to swim in the Cam, the viscosity’s too high! So, that was basically it. Ekhard did it all by ‘phone.

Whatmore:

Fantastic!

Scott:

Now, he has to, at some point, get this approved. So, how did he do that? What’s the committee and so on. He needs two world’s experts and they have to meet in the dining room of the Vice Chancellor of Cambridge, who at the time had been a Vice-President of IBM before – that was Alec Broers. And they have to convince him that they should just hire me because, in the end they’ll just hire me anyway because I’m the best candidate and it’ll save them a lot of time. So, he got Olly Bismayer to come in from Hamburg and Mike Glazer, from Oxford, who flew his own plane over, and they had tea with the Vice Chancellor, and the VC said: “OK, should I hire Jim Scott.” And Mike spoke up and said: “Yeah, he’s the best guy, fine.” And the VC said: “Thank you both for coming, don’t rush your tea.” That’s it!! Now, that would be extremely unfair if I were some young Assistant Professor, because you might get fifty better applicants, but I think it’s kind-of a funny story. So, it almost completes the story as you’ve now followed most of my career, and I’ve still never applied for a job.

St Andrews, Scotland

Whatmore:

That’s a great story!

Scott:

And then I came here, and that was even stranger. They’d had a search in Chemistry, not Physics, for a full year to hire a full professor. I had a big problem here. Their Physics Department is pretty darned good, and their Chemistry Department is pretty good as well, but in the last three years, they’ve lost three FRS. Three out of four quit. One went to be Director of the Max Plank Institute in Dresden, although he’s Scottish and doesn’t speak German, and has left-wing politics, which isn’t going to settle well in Dresden. The other two both went to Oxford, one as the Director of Biochemistry. You can’t be – it’s like being a second-division football team – you can’t be a feeder for Oxford and Germany. So, they tried to hire a replacement for one of these chemists. They did a year’s search. They narrowed it down to five interviews. The guys gave their interviews. Unfortunately, here the Deputy VC and similar people with strange titles are first-class medical doctors and biologists and things, and they said: “We’re not going to hire any of these guys. These guys are fifty. We’re going to have them here for fifteen to twenty years. That’s two million dollars just in salary. It doesn’t look like it’s worth two million dollars – two million pounds, rather.” So, they cancelled it. They didn’t hire anyone. So, about two weeks later, Finlay Morrison, who used to be my assistant at Cambridge, of course, went and said: “Listen, I know a guy in this field that you’re looking for – solid state chemistry, solid state physics or materials, who’s very good. He’s a bit long in the tooth. He’s elderly, but he’s got some good stuff left in him. Why don’t you think about hiring him?” So, Derek, the Deputy VC said: “OK, bring him up and let him give a talk. If the talk’s any good, then we’ll see.” I came up and gave the talk and Derek came over and said: “When can you start?” So, I started the day after I finished at Cambridge and I’ve been treated very well here. They have their own structural problems here, which have to do with what we were talking about earlier, but it’s basically a good university and I love the students.

Whatmore:

Working with the students is always the best bit.

Scott:

I love the Scottish students. They’re polite, they do things on time, they know they’re getting it free and they are really pleasant to deal with. I have absolutely no complaints about the students and it makes a big difference. And the best students are about as good as the ones at Cambridge. So, last year I had a student who was ethnic Chinese from Malaysia. As you probably know, those guys get screwed at home. There’s a quota for university entrance. So, he graduated with a double major. First in his class in Physics and first in Chemistry. And at this university, that’s not 50% physics and 50% chemistry. It’s all of physics and all of chemistry and he finished first in his class and he then won a gold medal for the best thesis for his Master’s thesis. The year before, I had a young lady from Lithuania: first in her class in physics, first in her class in chemistry. She won not just a gold medal from the university, she won a gold medal for all of Europe in an international competition for her thesis, and she’s now doing her PhD with Manfred Fiebig in ETH in Switzerland. So, if you’re dealing with top students, it’s going to be more fun, so I really shouldn’t complain. They’re just extending my appointment now for another eighteen months.

Whatmore:

And, ferroelectrics and ferroics are still very important to you?

Scott:

Yes. I have some changes of interest. I have become very interested in some strange things that happen below four or five degrees Kelvin.

Whatmore:

Really?

Scott:

Very unusual things happen with ferroelectrics. For example, domain walls can’t move by creep any more. They tunnel.

Whatmore:

Interesting!

Scott:

And there are some other similarly weird things. So, I would like to do a little more physics and maybe a little less chemistry for the year or two I have left, and I should be able to do that. But, work is going well. I three and half years here, I have one paper in Nature, one paper in Science, one paper in Nature Materials and another one submitted to Nature Nano this month, so ... Plus, a very large number of other papers done with collaborators in Puerto Rico or India or China.

Collaborations and Electrocalorics

Whatmore:

Collaboration has always been very important to you, hasn’t it Jim?

Scott:

Well, remember I never had a big group, so it’s a way of cheating! If you only have two students and a post-doc or two, then if you’re going to have more-breadth in your programme, then you’d better be able to work with someone in California, like Ramesh, or China ... And, one of the things that I’ve learned that might be useful for your readers, is that some of these full professors in China who are nearing retirement now, that I publish with, have been my assistants at Cambridge. So, if you treat these people professionally, when they go home, they remember and you’re still friends and colleagues and so-on.

Whatmore:

Yes, friendship’s really important.

Scott:

It is, and we all know people who can be very good scientists, whose ex-students wouldn’t even talk to them now. It does happen.

Whatmore:

Yes, it does happen.

Scott:

And so, I’ve been very fortunate. It’s not that I’m warm and fuzzy – probably the opposite – but occasionally, with hindsight, people realise that a “kick in the pants” on occasion can be beneficial. If you tell somebody: “Hey, you need to work a little harder”. One or two of the wives still hate me. One colleague from Cambridge - his wife hasn’t warmed up to me at all. I sent him home one day and said: “If you actually worked hard, you’d be one of the leader’s in this field in Europe.” He went home and told his wife, and she never forgave me! Because, then he started working harder. He’s very talented, but he’s got a wife and two kids. As I said to him: “You want a normal life. Physicists don’t have normal lives.” It’s not what we do well. Most of us are workaholics. And the reason is, if you have a normal life, then ... let me give you an example. A colleague here ... very competent scientist also from the same group – he told me one day that every weekend for twenty years he’s gone hiking in the hills with his wife. I said to him: “Every weekend for twenty years I’ve sat at the computer reading Russian literature for sixteen hours a weekend.” He said: “I have a normal life.” I said: “I’m a physicist!” You “pays your money and you takes your choice”. I think that’s allowed.

Whatmore:

What’s clear from my observations of your career is how you’ve seeded lots of very interesting things with very many different people. A good example is when you and Neil Mathur and Alex Mischenko came over from Cambridge to talk to us in Cranfield. You came to talk to us and said that electrocalorics were interesting, and you were interested in getting some thin films grown, and we were making thin films. That turned out to be a fantastically productive collaboration.

Scott:

I was one of the few guys in the world who knew the history. And what is most interesting about electrocalorics is who made the measurements. Why did this obscure guy in Baku later end up running the entire Soviet atom and hydrogen bomb project? Isn’t that interesting. Did you know he was?

Whatmore:

Igor Kurchatov? No, I didn’t know that.

Scott:

Well, there’s a good reason you wouldn’t know. His original paper – he measured the electrocaloric effect in Rochelle salt, which was miniscule – was published with his name badly transliterated into German in a way (Kurtschatov) that wouldn’t be acceptable nowadays, and certainly different from the transliteration into English. So, no-one would ever figure-out it was the same guy. But, because I have a Russian wife, I said to Galya: “This combination of consonants is impossible.” She said: “Oh, this is an early German variant.” I said: “Do you know who he is – he ran the Soviet hydrogen bomb project”.

Whatmore:

So, he was their equivalent to Oppenheimer or Teller?

Scott:

Yes. Well, I’ve put that into a couple of papers I’ve written because I thought it was so interesting. I asked Russians about this – like Tagantsev – and he said: “Sure, of course, everybody knows that.” I said: “You mean everybody in Russia knows it?” “Yes.” I get fascinated by these loose ends, these old things and I like reading old stuff, even the Russian stuff, and of course nowadays if it’s not in English and it’s not on the internet in translation, people don’t read it or cite it. So, I like to go back and read this old stuff by Walter Merz or Chynoweth. These were pretty good guys – or the equivalent people Bursien or Kogan or there were others - in Russia in the sixties, and they would typically do something that was brilliant and obscure. There was no follow-up, papers were not cited for fifteen years, they don’t develop it further and so I would go back and read these things and think: “Oh, gee, I’ll bet you with new materials and better equipment we might be able to do something with that.” So, I always tried to do that.

Whatmore:

Which was, effectively, what we did with the electrocalorics.

Scott:

Exactly! But because I have relatively few skills myself, I am then obliged to work with someone like you who can provide good quality materials and some other perspective and …

Whatmore:

Good science, in my view, is always about good collaboration.

Scott:

Well, there are guys who can do it all by themselves on their kitchen table …

Whatmore:

Not many these days, probably …

Scott:

OK. Feigenbaum and the theory of chaos, but I think these people tend to be theoreticians and if you want to do good experiments now, you either need ten million dollars-worth of kit, which none of us in Britain have, or you need to have some friends.

Conclusions

Whatmore:

So, what or who would you say was your greatest influence in your career

Scott:

On me, or by me?

Whatmore:

On you …

Scott:

Oh, certainly my thesis adviser. When I was at Harvard, I was surrounded by two kinds of kids in physics – the ones I’ve mentioned who came out of Exeter or Andover and had four years of physics before they hit Harvard and two full years of calculus before the first day – that was scary coming from my school – and then the other extreme was worse. These were the little guys with the yamakas, who would have four years at the Bronx School of Science, or New Trier at Chicago or Walnut Hills in Cincinnatti. Even they would have such wonderful stories. We had a kid, who became a full professor of logic at Princeton later on in his career, and he was the most-devout Orthodox Jew in the place, with long ringlets and the nodding, and he ate only cheese sandwiches for three meals a day for four years. We didn’t have kosher food at Harvard. I was there one day, and the professor came over to him and said – what was his name – it was a rather unusual name – Saul Kripke. At any rate, he said “Saul, I want to congratulate you on the first piece of work you turned in.” And as a freshman he was teaching graduate courses. He said: “It’s clear you take after your father.” Saul said: “Sir, I don’t understand what you mean.” The professor said: “There are two famous papers in symbolic logic and the author has exactly your name, and the name is unusual, so I just assumed this is your father.” And Saul said: “My father is a Rabbi, he doesn’t know any mathematics.” He said: “I wrote both those when I was in High School.”

Whatmore:

(Laughter)

Scott:

So, the point is, what I learned at Harvard was you are not in competition with these guys. You are just in competition with yourself – trying to find something you can do reasonably well and don’t pretend to be somebody else.

Whatmore:

And what are you proudest of – you’ve produced so much for us – what are you proudest of?

Scott: