Oral-History:Alexander M. Wilson

About Alexander M. Wilson

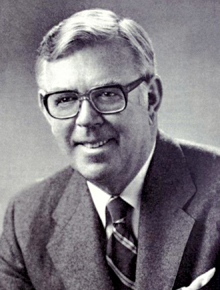

Alexander M. Wilson, retired Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer, Utah International Inc., has been involved in the mining industry for thirty-nine years. In his various roles as Director, President, Chief Executive Officer and Chairman, he led the transformation of Utah from a construction company into one of North America's most successful mining concerns.

Mr. Wilson received a B.S. in Metallurgical Engineering from the University of California in 1948. He joined. Utah as a metallurgical engineer in 1954, following experience with Bradley Mining Company and Molybdenum Corporation of America.

In addition to his corporate responsibilities, Mr. Wilson has provided leadership to many organizations including American Mining Congress, Bay Area Council, Invest-in-America, National Coal Association, National Coal Council, Pacific Basin Economic Council. San Francisco Zoological Society and the United Way. He has served on the Advisory Councils for the University of California. Berkeley, and for Stanford. He currently serves as a director for the Smlth-Kettlewell Eye Research Foundation, the Clarkson Company and the Fireman's Fund Insurance Company and is a member of the Kaiser Aluminum Retirement Committee.

Further Reading

Access additional oral histories from members and award recipients of the AIME Member Societies here: AIME Oral Histories

About the Interview

Alexander M. Wilson: An Interview conducted by Eleanor Swent in 1996 and 1997, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2000.

Copyright Statement

All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Alexander M. Wilson dated June 20, 1996. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley.

Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the Regional Oral History Office, 486 Library, University of California, Berkeley 94720, and should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user. The legal agreement with Alxander M. Wilson requires that he be notified of the request and allowed thirty days in which to respond.

It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows:

Alexander M. Wilson, "Leading a Changing Utah Construction and Mining Company: Utah International, GE-Utah, BHP-Utah, 1954 to 1987," an oral history conducted in 1996 and 1997 by Eleanor Swent, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2000.

Interview Audio File

Interview

INTERVIEWEE: Alexander M. Wilson

INTERVIEWER: Eleanor Swent

DATE: 1996 and 1997

PLACE: Berkeley, California

GROWING UP IN TULARE, CALIFORNIA, 1922-1941

[Interview 1: June 19, 1996]

Swent:

I think the place to start is the very beginning. You want to say where and when you were born and then let's talk a little bit about the Manleys and your family.

Wilson:

I was born in Tulare, 1922. I don't remember much until about age four or five. My parents were divorced when I was six years old. The man in my life was my maternal grandfather, Frank Creech, who took the place of my father.

Swent:

Did you live with your grandparents?

Wilson:

I did, I spent the summers with them. I think shortly after the divorce probably Mother and I lived with the grandparents for a year or two, but that's pretty foggy.

Swent:

How big a town was Tulare?

Wilson:

Those days, Tulare was about 12,000. We spent most of the time on Grandfather's ranch which was west of Tipton, which would put it about fifteen miles from Tulare. And that's where some of the greatest influences in my life occurred. Grandfather Creech was a very warm, honest farmer. Educated in Stockton, went to Stockton Business School, 1870, something or other. I had a great childhood.

I finally became reacquainted with my father later on, around the time I went into the army. Finally Father and Mother became friends; I saw a lot of him. After the war then Dad became part of our family. Bev thought a great deal of him and he spent a lot of time with us, so everything worked out fine.

Swent:

Do you have brothers and sisters?

Wilson:

No. I'm the only one. Raised essentially by my mother who was a schoolteacher. She was educated at San Francisco State College. I guess one of the greatest influences in my life was to have a mother who from the outset took it as a known that I was going to go to a university. No question about it, that was it.

Swent:

It seems to me it might have been a little unusual that your grandfather had gone to college. Farmers didn't always go to college at that time, did they?

Wilson:

Grandfather's father and mother came from Virginia. They arrived in California about 1849, I think 1848 they came into Monterey. Grandfather's father and his brother operated the mercantile store, department store in Stockton that supplied the gold fields.

Swent:

What was the name of it, do you know? Was it the Creech Store?

Wilson:

Don't know. No, I don't think so. That's one part of genealogy search that I haven't really launched on, I'm sure I could find out. What Grandfather's parents education was, I don't know. He went to Stockton Business School. Then, when the land began to become available for homesteading when the Southern Pacific Railroad was being built through the San Joaquin Valley, Great- Grandfather Creech went down there, bought land, and then started farming. That must have been 1870.

Swent:

Had they been farmers in Virginia?

Wilson:

I think so.

Swent:

Where did the Manley connection come in?

Wilson:

William Manley married my grandfather's mother's sister. William Manley was a fellow born and raised in Vermont who left home and went west, and west in those days was, to him anyway, was Michigan. He hunted and trapped in Michigan, during his time there developed a great fear of Indians. He did a lot of writing after he reached California. Throughout his books he evidences concern about the Indians, but anyway, William Manley and a fellow named Bennett left Michigan, Wisconsin or someplace up there, decided to go to California.

They got as far as the Sweetwater River in Wyoming, west of South Pass. They built a raft or they found a raft, and they killed their horses and jerked the meat, and started floating down the Green River. They got upended in Flaming Gorge and were rescued by the Indians. Took them to the Mormon Settlement, what is now Salt Lake City. In Ogden they joined a wagon train. They found a wagon train on which they had put their personal belongings, like clothes, and firearms, and ammunition and stuff when they took off on horseback. Then they joined another wagon train; when they got down to Death Valley, the wagon train got stuck there. Manley and Bennett walked from Death Valley to what is now Pasadena, and then back tracked up to El Tejon where they got pack animals and supplies, and they walked back into Death Valley and got the people out. He wrote a book called Death Valley Days in A9.

Swent:

He was an authentic hero.

Wilson:

You could say so. And he lived in San Jose. My family, Mother and her sister spoke of him with great reverence, "Uncle Manley."

Swent:

They had known him. One thing about that story that impressed me was that the families that stayed there were not at all sure that Uncle Manley and Bennett wouldn't just go up to the gold fields and forget them, and not come back.

Wilson:

That's right, but they had no alternative, they were stuck.

Swent:

But I mean that Manley and Bennett, once they got out alive they had no obligation to return and help those people, other than just a moral one.

Wilson:

Well don't you imagine in those days, in those kind of situations they did feel an obligation to go back. It wasn't something that he took it's hard to imagine the courage and fortitude that it took to accomplish something like that.

Swent:

It's a marvelous story. Good one to be raised on I would say. So he married your grandfather's sister.

Wilson:

Ended up being my grandfather's uncle, that was the connection.

Great grandmother's family name was Woods. Some place around here I have some genealogy on the Woods family. One of the Woods family's claim to fame I guess was that one of the female ancestors married Daniel Boone’s son. [laughter]

Swent:

That's pretty impressive.

Wilson:

Well, that's really not very interesting, that kind of stuff

Swent:

Is there anything interesting about the Wilson family?

Wilson:

I don't know much about them. The Wilsons came over from Scotland. Alexander Murray Wilson, I'm told--I haven't authenticated this--came from Scotland via Ireland. After the Scots lost one of the wars to the British, I don't know which, I haven't really followed that, there were three Alexander Murray Wilsons who arrived in the colonies before the revolutionary war. I haven't been able to pinpoint it; I'm going to try to do that. My father always said that the ancestor left Scotland ahead of the headsman s axe, or something like that.

Swent:

Did your father live around Tulare also?

Wilson:

Yes, he lived in Tulare, he spent quite a bit of time with us here.

Swent:

And your mother taught school.

Wilson:

My paternal grandfather was a doctor in Tulare. He was born in New York, got his degree in Chicago, married my grandmother, Emma Lang, in Cape Girardeau, Missouri. So you can see with that kind of background I was raised on tales of crossing the plains in covered wagons and cowboys and Indians, and all sorts of great and exciting things for a young fellow.

Swent:

You said your mother put a good emphasis on education.

Wilson:

Sure did.

Swent:

What did she teach?

Wilson:

She taught in grade school; she taught eighth grade English, both grammar and literature, and her interest was English literature. One of the things she took great delight in, which as far as I was concerned was bad, I skipped the seventh grade, I think it was. So I was always a year younger than my classmates, and that' sure put a crimp in my romance when I was in high school. That was terrible.

Swent:

Was she your teacher in the eighth grade?

Wilson:

No, no, she wasn't.

Swent:

It's interesting; a lot of people at that time did skip a year, didn't they? If you were very bright you were just moved up a year.

Wilson:

Which was sure bad on the kids from a social point of view; gee, it's terrible.

Swent:

You thought that was hard on you?

Wilson:

Sure was.

Swent:

In what way?

Wilson:

Well, you know, I was not physically as developed as the boys a year older than I, so when it came to sports I was kind of on the tag end of things. I was younger than the girls in the class so it was hard to get connected. It wasn't until I got out of high school that I really began to catch up with kids my own age.

Swent:

You're very tall; were you tall as a young boy?

Wilson:

Yes. Height wasn't but you know, when you're a freshman in high school, athletic ability, if you're a year younger than everybody else you just don't have the ability to compete.

Swent:

What sports did you like?

Wilson:

Oh, I liked football.

Swent:

So what else did you do in high school?

Wilson:

What did I do in high school? Oh, I took up archery. I was the runner-up State Champion in 19--State Junior Archery Champion in 1938 I guess it was. What else did I do, I hunted and fished I guess. I had a friend with whom I would fish in the Sierra. Fishing season started in the first of May so we would always ditch school and take a week off, go fishing.

Swent:

What was his name?

Wilson:

Don Bergance. Still lives in Tulare.

Swent:

Your mother let you do that?

Wilson:

No, I just did it.

Swent:

You did it anyway.

Wilson:

She was always terribly upset at all that stuff.

Swent:

Did you camp?

Wilson:

Yeah. On two or three occasions we rented a pack horse and walked back in a couple of days, in the Sierras, fished. We were serious fishermen.

Swent:

Did the Depression have a big effect on your life?

Wilson:

I think it did. With my mother teaching and Grandfather farming, you really didn't feel the effects of lack of money; we always had plenty to eat, automobiles. It's hard for me to say looking back. We were generally more economically well off than a lot of people were. What effect it had on me, I don't know.

Swent:

There were people coming in from the Middle West in those years to regions like Tulare, weren't there?

Wilson:

Oh yes, the big influx of folks came from Oklahoma and Texas during the dustbowl.

Swent:

You must have been aware of that.

Wilson:

Oh, sure. One of those families went to work for my grandfather on the ranch. Raised the children there, they all became successful farmers, third generation folks from that family farming there still.

I knew all that was going on but I always had a dime to go to the movies once a week. Plenty of good food, good clothes, so I was fortunate.

Swent:

What were the movies you liked?

Wilson:

Cowboys and Indians.

Swent:

And you mentioned cars; I'm always interested in what kind of cars people had. When did you start driving?

Wilson:

As soon as I could, what would that have been, age thirteen, fourteen, I don't know. Model A coupe with a rumble seat; boy, that was a neat car.

Swent:

Did your mother drive?

Wilson:

Yes, that was my mother's car.

Swent:

Rumble seats were a great thing, weren't they?

Wilson:

Grand-dad, Grandfather, always had a Buick; he liked Buicks. One family trip that we took during Prohibition, my grandfather and my uncle Art Patterson decided they wanted to go to Canada where they could get plenty of booze. We drove to Vancouver. I was just a little squirt. I remember that coming back at the border, Grand dad and Uncle Art had each a bottle of whiskey, and the customs fellow wouldn't let him bring it into the country. It was either pour it out or drink it, so he drank it. And then they played baseball all afternoon to wear it off. I thought that was great.

Swent:

You haven't mentioned your grandmother; was she in the picture?

Wilson:

Oh yes, Grandmother Creech was very much in the picture.

Grandmother Wilson was very much in the picture when I was young, probably the two grandmothers, as I recall, fought each other tooth and nail and that probably was a cause of the divorce of my parents. But who knows.

Swent:

This trip to Canada; was the grandmother along on that?

Wilson:

Oh yes, the whole family. There was Mother and I, Grand-dad, Grandmother, Mother's sister, Rita Patterson, and her husband. There was probably someone else along too; seemed to me there were three cars. Each family had an automobile; there were three or four cars.

Swent:

That must have been a memorable trip.

Wilson:

I can't remember how old I was. When was Prohibition repealed, do you remember?

Swent:

Was it 32, something like that? I'm not sure. Early thirties. Did you do things like Boy Scouts or church?

Wilson:

Oh, yes, went to Boy Scouts; it was kind of tough living on a ranch twelve miles from town, but we made it. I was in the Boy Scouts two or three years but I think I dropped out because it was so hard to get into town. So that wasn't a big factor in my life.

Swent:

Did you go to church?

Wilson:

Occasionally, not regularly; went to Sunday School. But again because we were out on a ranch, in those parts when I was young--

Swent:

When you were in high school were you living in town?

Wilson:

I lived in town in high school. We d go to church occasionally, but it was not a big part of our life.

Swent:

Did you get good grades?

Wilson:

Yes, I got good grades.

Swent:

Your mother saw to it?

Wilson:

Yes. Graduated in 1939. I was good at math and I liked sciences. There was a great debate at that time on what I should do, and finally I went to Visalia Junior College, which is a pretty darn good thing, being as young as I was. Seventeen and probably younger than most kids at seventeen.

Swent:

When is your birthday?

Wilson:

May 17. So I guess I was two years at Visalia Junior College.

Swent:

Did you commute there?

Wilson:

Yes, from Tulare, about twelve, thirteen miles,

Swent:

And you drove every day?

Wilson:

Yes.

Swent:

The war was on the horizon.

Wilson:

It sure was.

Swent:

Were you aware of that?

Wilson:

Oh, yes.

Swent:

In what way?

Wilson:

Well, from the news.

Swent:

Were any of your high school friends enlisting right away?

Wilson:

Probably about that time. Then I must have gone and started Berkeley in 41. Fall of 41, that's not right.

Swent:

Well, let's see, if you graduated from high school in 39 and went to Visalia for the year.

Wilson:

Maybe I went to Visalia one year.

Swent:

That was 1939, 1940.

Wilson:

I guess I started at Berkeley in 41 and then I left in 42; would that have been right?

Swent:

I'm trying to think; 39 to 40 you were at Visalia. Then the fall of 40 to the spring of 41 that school year.

Wilson:

I went to Visalia two years.

Swent:

Stayed at Visalia two years, and then the fall of 41, that's when Pearl Harbor was.

Wilson:

So I started in those days UC Berkeley was running they had to run three semesters. I started in spring, went to school in the summer, so when Pearl Harbor occurred I was in my second semester at Cal. And then I left in October 42.

Swent:

What did you have to do to get into Berkeley in those days?

Wilson:

I had to have a B average, 3.0. That was about it.

Swent:

How did you get to Berkeley; did you drive?

Wilson:

Yes, drove the Oldsmobile coupe.

Swent:

This was your very own car by then.

Wilson:

By now, yes.

Swent:

Had you had jobs, did you have time for any--I know you helped your grandfather on the farm but did you do anything else?

Wilson:

When I was going to high school I worked at a grocery store called Linders. I worked in the vegetable department. One of the jobs that I really liked in the vegetable department was--eggplant shrivels when it begins to be dehydrated. The way you make shrivelled up eggplant look really nice again is put a needle on the end of a hose, stick it in the eggplant and fill it full of water. That was my job, to keep the eggplant nice and glistening, with little droplets of water coming out of the skin.

Swent:

Is that a useful skill in your later life?

Wilson:

It sure was.

Swent:

Do you like eggplant today?

Wilson:

Yes, I do.

Swent:

Good.

Wilson:

I worked at a service station in Berkeley, down on Bancroft Way. First year there I lived at a place called Barrington Hall. I lived there because this is the cheapest place I could find. And it was a cooperative, a co-op.

Swent:

How much did it cost?

Wilson:

I have no idea. But you lived there and everybody did some work, served tables, cooked, washed dishes, mopped the floor, did all that sort of stuff. I had a room that had off one side a rather large closet and in that closet lived a fellow named Rossy Lomowitz. Rossy Lomowitz was a physicist.

Swent:

He lived in the closet?

Wilson:

Yes, he lived in the closet. Rossy was in those days the youngest person to obtain a Ph.D. in physics, age eighteen he got his Ph.D. Rossy was also the head of the Young People’s Communist League on campus. When Rossy had his cell meetings, all these young Communists had to climb over my bed to get into his closet, [laughter] He tried to recruit me. Very helpful in tutoring though, mathematics. Tried to recruit me and I was just off the farm, I was so dumb I didn't know a communist from Adam’s off ox and I simply wasn't interested. Rossy would give speeches at Sather Gate about, which in those days, what had happened. By that time Germany had turned on Russia, for the Soviet Union, so we were allies. He was drumming up enthusiasm, support for the Soviet Union. So that was a lot of fun.

Swent:

But it didn't appeal to you.

Wilson:

No. I was not political in those days. I guess when I went to Berkeley I had already decided I wanted to go into the Mining College. Hearst School of Mines.

Swent:

Why?

Wilson:

Couple of things I guess; in junior college one of my teachers taught geology. I took Geology 1 and, man alive, it just excited me to learn about how the earth was formed and all that stuff, that was the best thing in the world.

Swent:

Was there a particularly exciting teacher?

Wilson:

Must have been, I've forgotten. The whole subject just really fascinated me. I'd worked for a surveyor as a chainman and a rodman through high school, through the father of a friend of mine. Hugh Pennebaker. Mr. Pennebaker was the county surveyor, did a lot of surveying in that part of the world. That interested me. I took surveying in junior college, then of course I got exposed to physics and chemistry and all that excited me, and I put it all together and the liking of geology, that's mining school at Berkeley.

Don McLaughlin was the dean of the school at that time. And I almost flunked out; I got to Berkeley and I found girls and night life in San Francisco. Boy, I tell you, you turn a young kid loose off the farm, an environment like that it is pretty tough. So at one point I had to go and petition Don McLaughlin to let me stay in school. Interestingly enough many years later he and I became very good friends.

Swent:

So he had the wisdom to let you stay.

Wilson:

The war was going on.

II WORLD WAR II AND SERVICE IN THE ARMY, 1942-1946

Swent:

Pearl Harbor must have been quite an event.

Wilson:

That's when things got very difficult at school, because the war was going on. There was a great pressure to get out of school, pressure by peers, become involved in the army. I thought I was having so much fun, my grades were really not good. I knew I was going to be drafted and I decided boy I better get out as soon as I can before I flunk out. There was an engineering unit recruiting in San Francisco. I decided that was something that I wanted to do. Because I was under age, I had to get my mother's permission to withdraw from the university and enlist in the army. I had an appointment with the dean of men. That appointment was significant because when I came back to school after the war, my records showed flunks. I had Fs in all of the classes that I was taking at the time I withdrew. Instead of having an incomplete, they flunked me. There was no record of my having petitioned for whatever it was you petitioned for, to leave school during the semester. I finally found a girl who worked in the dean s office who was a friend of mine, I guess from Tulare high school. She diligently searched the files and found an appointment slip, that I had had an appointment with the dean of men in 1942. And on that basis they erased the Fs and gave me incompletes on all those courses.

Swent:

A lot of things changed because of that I'm sure.

Wilson:

By that time I had grown up and I was pretty darn serious about finishing my education. From then on, as far as grades were concerned, it was smooth sailing.

Swent:

So what was your army career; when did you join the army?

Wilson:

Joined in 42.

Swent:

You were twenty years old.

Wilson:

Enlisted for the next year, we went to Burma, went to India. San Pedro to Bombay, India. Forty-three days, that's three days longer than Noah was on the Ark. Then a train through India up to Ledo, India, and then later aircraft into Myitkyina.

Swent:

Ledo?

Wilson:

Ledo was the end, furthest point northeast. That was the dropping off point for all the combat troops who went into Burma. Was the railhead of the Burma road, what finally became the Burma road, the overland route into China from India.

Swent:

What group were you with?

Wilson:

I was with the aviation engineers.

Swent:

Aviation engineers.

Wilson:

We were supposed to build airfields. We went into Burma, things were pretty hot. The infantry unit that had taken Myitkyina just before we got there was in pretty desperate straits, so all of the troops that arrived in India at that time were sent over to Burma as infantry. When Myitkyina was secured then we did reform again into this aviation engineer unit and built an airfield across the river from Myitkyina. Built another airfield in Bahmo, Burma. Went from there, convoyed into China. I lost track of time, probably 44, went into China in 44. We were the second convoy over the road, it's opened. Went from Bahmo to Kunming, and then from Kunming down to the border with China and Vietnam. Place called Mengsee, built an airfield there. It's all pretty hazy. Back to Kunming. I was sent off to supervise the construction of airfield in a place called Lung Ling which was north in China on the border with either India or Burma; I'd have to look at the map. Well, I went from south China up to the north. We'll get an atlas.

Swent:

By then you were supervising a construction crew.

Wilson:

I was a platoon sergeant. What I supervised was a crushing plant that consisted of something like 6,000 women all with hammers beating rocks to make aggregate for the airfield.

Swent:

These were Chinese women, or Burmese.

Wilson:

All Chinese. Everything was done by hand in China. The excavation was all mattocks, and shovels, and stuff carried out with baskets. The rock for the sub-grade was carried from the crushing plant in baskets, laid about twenty-four inches thick. Then we got sand from some place, I guess a river or some place, carried all on backs of people. It was a B-29 base we were building. I used to remember the quantities of materials that were hand-delivered; it was huge.

Swent:

So you didn't have to do any manual labor yourself.

Wilson:

No, just to kind of organize all this mass of humanity.

Swent:

What a job!

Wilson:

That experience in China, Burma and China, really got me interested in Asia. My friend who was back here after the war tried to encourage me to go back, I don't know what in the world happened to him. Those days the only way to make money was buying opium from the poppy grower.

Swent:

Did you see a lot of that?

Wilson:

No. The Golden Triangle, that's the description the press has used to describe this area, Burma, Thailand, China, where much of the opium is produced. The folks who started that opium growing were deserters from the Chinese army. Tens of thousands of Chinese army, whole divisions deserted along that Burma border. The remnants of that, those folks started opium growing, organized the opium trade.

The U.S. Army had a great deal of difficulty with those Chinese army deserters. They turned into bandits and preyed on not only the civilian population, but the military traffic going on the Burma road, from Burma into China.

Swent:

You felt that these people introduced the poppy growing there?

Wilson:

No, they didn't introduce it but they organized it. This is what I felt, I didn't know that at the time. It's what I've read since then, these folks are the ones who are responsible for a great deal of that opium that came out of there during the Vietnam war.

Swent:

Did you see Japanese troops?

Wilson:

Yes, from a distance. Ones that I saw close up were smelling pretty bad.

Swent:

Were you in actual combat then?

Wilson:

Yeah. In Myitkyina and again in Bahmo.

Swent:

You skipped by that, you said "secured the area." Securing that meant actual fighting.

Wilson:

Oh, yes, Japanese didn't want to give it up. Japanese were in there on the end of a very long supply line. When the Americans secured the airfield, and were able to fly in supplies and people, from India, just overwhelmed the Japanese, they had to move out.

Wilson:

Many years later, when I started doing business in Japan I met the then head of Mitsui Shoji whose name was Mezeki, who was the quartermaster; he was a general in the Japanese quartermaster corps responsible for supplying those people in Burma. Had a number of interesting conversations with him about the war days. Interestingly enough he was really happy to talk about it.

Swent:

In what sense?

Wilson:

Historical stuff, not really a historical thing but subjective, how they felt.

Swent:

What did he say?

Wilson:

Well, the troops were very concerned because the quartermaster corps was unable to supply them with much of anything. By that time the U.S. Air Force had control of the air during the daytime, so they had difficulties with convoys, getting supplies up into north Burma. And they just had to retreat, down in toward Rangoon, where they were being supplied by rail from Thailand.

Met a lot of Japanese who had been involved in the war, one way or another, in later years.

Swent:

You said you became very interested in China but you didn't go back.

Wilson:

Well, in the whole of Asia. No, I didn't get back to China until about 1980, was the first trip. In ’81 Bev and I went to China and then spent a week in Tibet, which was pretty darn interesting. In the meantime I had spent a lot of time in Japan.

Swent:

You had a lot of business dealings in Japan, Did you ever get back to Kunming?

Wilson:

No, I didn't go back.

Swent:

That would be interesting.

Wilson:

Yes, it would; I thought about going there. Pretty difficult. We went to Tibet as guests of the Chinese government, so we had a young woman who was our guide. Really we were not invited to tour China.

Swent:

No, 1980 was awfully early.

Wilson:

We're doing an awful lot of rambling here.

Swent:

No, no. We've just rambled a bit just now from your crushing plant. The Burma road and the flying over the Hump; I'm trying to just get this straight in my own mind that the land route was developed after the air route?

Wilson:

Oh, yes. You heard of flying the Hump. The United States Air Force combat cargo squadrons flew from Ledo, India, to Ledo out of a place called Dibrugarh to Kunming.

Swent:

And then after the road was built--

Wilson:

They were flying supplies in to the Chinese Army.

Swent:

Did you fly at all at that time?

Wilson:

Only as a passenger. I went to China, went to India one Christmas to buy supplies, mainly Debragah gin and fighter brand whiskey. The gin and the whiskey were bottled in used beer bottles.

Swent:

But this was an essential supply, Did you have any health problems through all this?

Wilson:

Malaria, I had malaria. More times than you could count. When I first went into Burma, if one had malaria six times then they could ship them off. So I went into the hospital on a stretcher, my sixth time the doctor said, "What are you grinning about?"

I said, "This is number six," and he said, "Oh that's too bad, they just rescinded the order, if we sent everybody out who had malaria six times we wouldn't have anybody left in Burma." So that vas the end of that. Later the doctor said—I’d had asthma when I was a kid, I was allergic to a lot of things. So the doctor said, "If you have asthma we’ll ship you home." I knew that I had been allergic to ragweed, and there was this whole tent hospital was, right down the biggest patch of ragweed you ever want to see. So I got out there and I sniffed the--

Swent:

So where was this tent hospital?

Wilson:

In Myitkyina.

Swent:

And there was ragweed there?

Wilson:

Oh, sure was. But I couldn't get a wheeze out of it, so I had to stay.

Swent:

You must have been pretty ill though, with the malaria.

Wilson:

I was one of the few, I think 14, 15 percent of the folks in whom atabrine did not suppress malaria. Atabrine was the principal anti-malaria drug that supplied the army. So I had malaria pretty regularly, about every six weeks.

Swent:

Did you ever have it later; did it recur?

Wilson:

Yes, I had it when I went back to Berkeley and I volunteered as one of those on whom they tested the malaria drug, one that became very common, I forgot the name of it now. When I went to work up in Idaho I still had malaria. I guess I got over it in about, probably by 1952 or 1953.

Swent:

You probably still have it in your blood though, don't you? They won’t take your blood.

Wilson:

That's right, they won't take whole blood.

Swent:

It has a long lasting effect I guess.

Wilson:

When we were convoying from Kunming to Mengsee, we sunk a ferry. Some place around here I've got some photographs, and I got malaria when this convoy was stuck. I got malaria pretty badly and I'd had it when we left Kunming and I'd prevailed on the hospital to give me some quinine rather than put me in a hospital, because I didn't want to lose track of the unit. So I went out and I woke up in a bathtub full of ice cubes. What had happened, I’d become unconscious. There were some locals with dugout canoes on this river, and they put me in a canoe down the river a days paddle to a French Army hospital on the border of China and Vietnam. And that's when I woke up.

Swent:

And they had ice.

Wilson:

They had ice, yes.

Swent:

Probably saved your life.

Wilson:

I suppose so, I must have been pretty hot. That was about the last real tough malaria experience I remember. Anyway, didn't get shot, so I was pretty lucky.

Swent:

Good. You were there a long time.

Wilson:

I came back, since the war was over August "45, I finally got back in January 46. We had a problem with the Chinese provincial troops when the Japanese surrendered. They tried to take the airfield in Kunming. Attempted to take the engineering supply area where we had probably fifty or sixty 155 Howitzers. So we had a big problem with them, for ten days after the war was over, which I always felt was unfair on the part of those folks.

Swent:

To whom?

Wilson:

Unfair to us. The war was over! That was a little part of the military history of this country that was never written. That was kept secret, at least from the press, because of Marshall s attempt to have a coalition government formed, of the provincial troops and Kuomintang. Which of course finally resulted in the Chinese Nationalists going to Formosa, what is now Taiwan. So that was over and then things settled down.

Swent:

Were you there at Kunming at that time? So you were aware; you were in it. Give us an eyewitness account.

Wilson:

Kunming was an old, old city and the inner part of Kunming had a wall around it. When the provincial troops rose up, it was the day after the surrender of Japan was announced. They shut this big wooden gate, and inside the city was the Armed Forces radio station and a U.S.O. hostel. The Armed Forces radio station had four guys in it, who were American, civilians I guess, or maybe they were military. The U.S.O. had six American girls trapped inside of this hostel area. So four halftracks, that's a vehicle, with round front wheels and tracked wheels in the back, with 50- caliber machine guns mounted in the bed of this thing. We had to go in and rescue these folks. So we got a 155 Howitzer--

Swent:

Were you in all of this?

Wilson:

Yes, blew the gates down, I was in the second halftrack. And we went in like a bunch of cowboys, we went through there shooting at everything that moved. We went to the Armed Forces radio station, we got those guys out, and then backed up to the U.S.O., got the girls out, backed out of town.

Swent:

Put them into the halftrack, and then away you went.

Wilson:

That was a lot of fun. You know I've read everything I can get my hands on about China in those days. Not a peep, nothing was ever written to my knowledge about that whole episode. I mean about the episode of the Chinese provincial troops uprising after Japanese surrender.

Swent:

So the Kuomintang people were there at the airfield; were they the ones who were in control?

Wilson:

Politics were pretty confused at that point. There were no Nationalist troops, the governor of Yunnan province in which Kunming is the capital, the governor was, I'm not speaking with great authority here but somehow or another, while he was allied with the Nationalists, Chaing Kai-Shek and the National troops, he was attempting to do something on his own. But when the war began to wind down it became apparent that the Japanese were about to be conquered, and I'm not sure that this was before the atom bombs were dropped, I think it was before. The Nationalist troops in an attempt to gain entry into Yunan province offered the governor of Yunan province opportunity to take Thailand, to move down into Thailand. So the theory being, I guess, that he had to send all these troops down there and then all the National troops would come back. Well, that didn't work that way because the governor then turned Communist. When the Japanese surrendered, his troops were not far away and they came back. I guess by this time the Nationalists did have infantry on the airfield. It was the governor s troops who were the Communists.

I was in the hospital with malaria at that time. They evacuated the hospital. All those who had a temperature exceeding 102 were flown out, and presumably flown home and those whose temperature was 102 or lower had to walk back to town. That was about eight miles from the airfield. I couldn’t get my temperature to go to 102, so I was one of those that had to walk.

When we got back, the good guys had black armbands and the bad guys had red armbands and we d go through one road block after another. For some reason or other we didn't have any trouble with the red armband fellows, they let us through. But then we got back to town, that's when the fighting erupted. So I missed a couple of opportunities to get out of there.

Swent:

You said the old city was walled, and you were based outside the city, and the hospital was eight miles-

Wilson:

Beyond where we were based.

Swent:

So it was after you got out of the hospital that you rescued these people then? And there was fighting at the airfield.

Wilson:

We were in the engineering depot, which was probably two miles from the airfield. That's all kind of hazy too.

Swent:

That's very interesting. Which group then won the battle of the airfield?

Wilson:

The provincial troops were finally subdued; they were unable to take the airfield.

Swent:

Was that when they started that long march then, from there up to the north?

Wilson:

Well, I don't know, I'm foggy on that. I think the folks who started the long march, they started in the Peking area, didn't they? Beijing, the capital, I don't know.

Swent:

I thought they started in Kunming and then went north, but I could be wrong on that. You were there at an exciting time. But then you didn't get back till December, so you hung around a while.

Wilson:

I was glad to get out of there. I was one of those who had accumulated points, they developed a point system, you had so many points for a year overseas and so many points for this and that. I had points the highest I recall, 151 points so I could immediately be discharged, but getting home was a problem, because everybody was going home. So we flew out of China and went to a camp in Calcutta. So I spent about two months or three months there waiting for a ship.

Swent:

That must have been terrible.

Wilson:

Finally got on a ship to come home some time in December, because I was we passed Gibraltar on New Year s Day.

Swent:

Gibraltar?

Wilson:

Yes, we came back through the Mediterranean. From India, through the Suez the Red Sea, through the Suez Canal, then down the Mediterranean, that's the way.

Swent:

What kind of ship were you on?

Wilson:

Oh, some sort of a troop ship. Going over, we went from San Pedro to Suva, Fiji Islands, Suva to Melbourne. Melbourne to Perth, picked up a British naval escort, went up through the Indian Ocean, I suppose as far away from Singapore as we could get, which would put us over toward the African coast. Went into Bombay.

Swent:

From Melbourne to Perth how did you do it?

Wilson:

Well, that was all on troop ship, but we stopped in Melbourne, and then went around Australia to Perth where we did not stop but we picked up the escort.

Swent:

South or north?

Wilson:

Around the southern part of Australia. Picked up the British cruiser and sixteen destroyer escorts, one troop ship. We were traversing an area in which the Japanese controlled the air. But we got through unscathed.

Swent:

So when you came back you came into New York then? Must have been exciting.

Wilson:

Sure was, yes.

Swent:

Had you been able to get mail? You did get letters.

Wilson:

Yes, I did get letters. It took a month or so. No radio, it took a month or so to get letters out there.

Swent:

So you landed in New York.

Wilson:

Where’d we go, we went from New York to some army camp, and then stayed a day or two there and were flown to Los Angeles, got my discharge in L.A. Boy, I was happy.

Swent:

I'm sure you were. Did you go straight to Tulare?

Wilson:

Yes, I did. Smartest thing I ever did was when getting discharged, some officer gave us a big song and dance about the benefits of joining the reserves. They said all those who wished to join the reserves line up over here; I didn't move. Of course those guys went to Korea, went to the Korean War. But I didn't, and I wasn't called up for the Korean War.

Swent:

You'd seen a good bit of war.

Wilson:

I survived. Looking back on it, I had a lot of fun.

Swent:

Did you?

Wilson:

Yes, sure.

Swent:

Doesn't sound like it.

Wilson:

You forget the bad things, remember the good things.

Swent:

What were the good things?

Wilson:

Oh, having fun shooting up Kunming.

Swent:

Have you kept friendships from then?

Wilson:

No. With the Chinese that I knew, I have no idea what happened to them. There were Chinese university professors in Kunming who liked to speak English and have the military folks around, so once a week we had a little get-together with these Chinese folks in one of their homes. It was a discussion meeting, history, politics, really very interesting. We wanted to know as much as we could about their society and they were very curious about ours; it was a lot of fun. I often wondered what happened to them, suppose the Communists shot them all.

Swent:

How did they happen to select you?

Wilson:

I have no idea. I don't remember.

Swent:

They must have been looking for people with some education. Your American buddies, you haven't kept in touch with?

Wilson:

No, I was so happy to get out of the army, Lee, that I just--I kept in touch with a few of them, but I lost track of them. Some military folks take great delight in recapturing the old days and they go to annual meetings and stuff, that wasn't for me. Like I told you about doing this interview.

Swent:

You'd rather look ahead than look back.

Wilson:

That stage of my life is over, I've got a new one going now.

Swent:

That's good. I'm thinking your mother must have been awfully happy to have you back home, and your grandparents. That was a bad time.

Wilson:

That's when I really got to know my father, after I got back out of the army, because he was married, remarried. He and mother were very friendly and we just saw a lot of each other. Shooting, Dad, and Grandfather, and I would go out dove hunting, that was a great thing in Grandfather's life.

Swent:

This is your Grandfather Wilson.

Wilson:

Grandfather Creech. Grandfather Wilson died before I was born, so I never knew him.

Swent:

Maybe it was the war that made your parents concerned over you?

Wilson:

Well, so much time had passed and the old bitter stuff was all history, and mother and father liked each other in spite of all the problems that they had. I was living with my mother, I was living with her at the time, and saw a lot of Dad. I'm sure I was a real problem for mother because she wanted to treat me as a little boy; I got back from the war and I was doing my own thing. When I would get to Visalia and have a party and stay in a hotel instead of coming home, boy, Mother would get awful upset. But I had to tell her I had a life to lead and that was it.

Swent:

Your dad backed you up, did he?

Wilson:

Yes, he always backed me up, even before. After their divorce, I guess when I was in high school I got in trouble from time to time. I got put in jail for trying to swipe gasoline. Dad was always there; he got me out. Twice I was in jail in high school. Once for swiping gasoline and the second time we were decorating for the junior-senior prom and we were doing this jungle theme, I was a junior in high school. So where do we get vines? Well, the most prolific vine growing was on the mortuary. So we tore all these vines off as the decorations, decorated the gym and oh God, [laughter] the next day here comes--so they put the whole bunch of us in jail, the whole decorating committee.

Swent:

Seems kind of mild now, doesn't it?

Wilson:

I guess the cops were; I think they were having a great time doing that, [laughter]

III RETURN TO THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY, 1946-1948

Swent:

They must not have had much serious crime to deal with.

Wilson:

One of those persons was named Anita Whistler. Anita Whistler was an English instructor at UC Berkeley, in the English Department at Berkeley when I came back after the war. Before the war, I had never passed a Subject A exam, because my spelling was terrible, I couldn’t spell anything. I was required to take Subject A. But I knew I was going to have an awful time because I was trying to start out as a junior in calculus and physics and chemistry and all that stuff. So Anita was one of those persons who was lined up in front of they’d have A and then a person there taking all the A s. She wasn't under the W s, but I spotted her and I made a deal with her. I said if you get me through Subject A I’ll take you to dinner once a week. So Anita did, she got me in her class for some reason or another. Every Friday night we d go to a Chinese restaurant on Shattuck Avenue. [chuckles] But see, finally she wrote me a note one day and she said, I have to have something in your handwriting, you’ve got to do an essay. She says you have to come to class at least once.

Swent:

You weren't even going to class?

Wilson:

No, I wasn't. So I had to call her and find out where the class was. She got me through Subject A.

Swent:

Without your going to class?

Wilson:

Yes, I went to class once. She was neat, then she went from Berkeley to England, and I think she taught at, maybe it was Oxford. And she was flying from London to Rangoon, Burma. She had a job, and she vas on the first jet aircraft that blew up in the air, so she was killed. That was probably ’48, ’49 I suppose.

Swent:

What a shame.

Wilson:

I don't remember; I think it lost an engine. it

Swent:

We missed something in the tape change here. You were talking about where you were in the army and in that part of the world yourself; you went from Bombay to Calcutta.

Wilson:

Going there, landed in Bombay and we took a train from Bombay to Calcutta--

Swent:

Three weeks!

Wilson:

And then from Calcutta up into Assam Province to near Debragah. Three weeks; it was a long train trip. When we did it we came up through what is now Pakistan, of course Calcutta and up. The British were fighting the Japanese along the Burma border, and I can remember they dressed the locomotive, this train up with banana plants. They had banana plants, banana stalks out of the smokestack and tied to the locomotive.

Swent:

To conceal it.

Wilson:

Yes, try to conceal it. We had a platoon, twenty-six men in the platoon. We were in a car, wooden passenger car. Everybody could lie down, we used the baggage racks, the benches, and the floor, and one man had to sit up. [laughter]

Swent:

You took turns?

Wilson:

We took turns, yes.

Swent:

Did you just eat off the land as you went along?

Wilson:

I think we were supplied with K rations, dry block stuff. I don't think we had anything else, we didn't have any kitchen. Just all K rations, pretty awful food.

Swent:

Probably safer than what you might have picked up along the way though.

Wilson:

Absolutely. So that was my travel around that part of the world.

Swent:

I was interested in your saying you took Anita Whistler out for Chinese food; your period in China didn't spoil your taste for Chinese food.

Wilson:

Well, I think it's probably because that was the cheapest food there was in Berkeley. [laughter] I like Chinese food.

Swent:

Have you been back to India?

Wilson:

No. Closest I've been, I've been in Thailand a number of times. Bev and I took a trip to Vietnam a couple of years ago, Stanford alum trip with Admiral Stockdale and his wife. That was a great trip.

Swent:

I've heard of that; that must have been wonderful.

Wilson:

They’re great folks.

Swent:

I read his book.

Wilson:

Isn't that something? Boy, what a guy. They broke his knee; his right leg is stiff and he has to swing it while he's walking. He said one day to Bev as he was going down the gangplank, he says, "I think this gives me a distinguished look, don't you?" And he was swinging that leg around. He's really something, that fellow.

Swent:

He is. So shall we get back to Berkeley: you got through Subject A; what else did you take when you went back? You said you went back different from what You'd been when you left.

Wilson:

I should say so; I'd grown up in that time.

Swent:

Now you really knew what you wanted to do?

Wilson:

I wanted to get out of school just as quick as I could and start earning a living.

Swent:

But you stuck with the same courses though.

Wilson:

I think I got straight A s after coming back here. Another anecdote: to go back as a junior, I had to take a junior engineering exam, which was a comprehensive exam of all the basic science stuff. Math, physics, chemistry.

Swent:

You were a long time away from it.

Wilson:

Yes, and this was an all-day exam, I think it started at eight, had lunch and got through at four. And I was sure I flunked it, Christ, I couldn’t remember calculus. The Dean of the school the Mining School had been consolidated with the Engineering school. That year, the first year Dean of Engineering was Don McLaughlin.

Wilson:

Second year I was back it was O Brien. I kept waiting for this notice, saying "Uh oh, you flunked the test, and they'll throw you out." It didn't come, it didn't come, finally right up to the time I graduated, we graduated in 48, they had a ceremony at the Greek Theatre I guess it was. Harry Truman gave out the diplomas, he handed them out, shook hands with everybody. As I was walking down the aisle and my name was called, I expected somebody from the dean s office to jump up screaming, "Oh he didn't, he flunked the exam!" Many years later I retained O Brien to do some consulting work for us on--his field was the littoral movement of particles along coast lines. We were building a port in Western Australia, Port Hedland, had to dig a channel, and we were interested in which direction this channel should go, to obviate the necessity of having to dredge it constantly [knocks twice on table]. So we hired O Brien to consult with us. At a meeting, joint venture meeting which O Brien gave his conclusions, I related to him this episode, this fear, and he said, "Didn't they tell you? Anybody who d been out of school more than two years we threw the exams away." [laughter]

Swent:

All that worry for nothing. So you got straight A s this time around; what were you taking?

Wilson:

Taking extractive metallurgy.

Swent:

Who was teaching it?

Wilson:

[Lionel] Duschak was head of the department, grand old man. I took a number of geology courses too. The man who taught economic geology, mining geology, whatever they called it in those days, Carl Hulin. Did you know him?

Swent:

Yes.

Wilson:

Is his wife still alive?

Swent:

I don't think so.

Wilson:

Well, anyway, Carl was a very opinionated gentleman. He got in a lot of trouble trying to deal with the adult students that he had, who had come out of the war. Carl was inclined to be pretty--in some respects he would say demeaning things to students, I guess his way of trying to prompt them into doing better. He said something in some petrology class to some fellow who had been in the Rangers, and who had scaled the walls, landing in Europe, you know, one of these guys who really knew what his life was all about and Carl called him an idiot and the guy punched Carl in the nose. They had a big fight; well, anyway--.

So I got through, I took my final into Carl s office, he says, "What's the matter, aren t you smart enough to spend four hours doing this?" And I handed him my blue book and I said, "Read the blue book." He put it down and he said, "Do you want a job?" And I had--Bev had typed application after application, we d sent them to everybody I could find, every mining company. So I said, well that's what it's all about, and he said, "Well, I've got a job for you." That was with Bradley Mining Company; he was a consultant, he was a consulting geologist for Bradleys. He arranged for me to, arranged the appointments and I flew to Boise with one of my classmates, Bill Griswold, who had been a fighter pilot for the A.V.G., American Volunteer Group that flew for the Chinese during the war. Bill had the closest thing to a P-51 that he could find was some kind of a single engine low-wing plane; he flew me up to Boise, he had already accepted a job at AS&R [American Smelting & Refining Co., Asarco] , in Arizona I guess. We went up to Boise and then we flew up to the mine, up to Stibnite, the Yellow Pine Mine, where I was interviewed by the fellows. The superintendents and finally the manager.

IV WORKING AS AN ENGINEER FOR THE YELLOW PINE MINE, STIBNITE, IDAHO, 1948-1951

Swent:

Do you remember their names?

Wilson:

Oh yes, Bob McCrea was the mill superintendent, Bob Clarkson was chief engineer, and Harold Bailey was manager. During this conversation with Harold Bailey, he asked me what my wife did.

I said, "Oh she's a schoolteacher." He was terribly interested because they needed a schoolteacher.

He said, "Would she teach here?"

I said, "Well, gee, I suppose so; she likes to teach."

"You're hired." So I've kidded Bev that she was the one that got me the job. And she did teach for two years.

Swent:

Where did you meet her?

Wilson:

Bev and I met in Visalia. We met at a track meet. I was in Visalia with a friend; this was probably the spring of ’46. I was in Visalia with a friend who had a date; he wanted to arrange a date with Bev’s sister, who was queen of the track meet, something. So he, much against my will, got me out of the bar and we went to Visalia Junior College track meet. So he met Gloria, his girlfriend, and introduced me to the family, and gee, I saw Bev, my God, just swept me off my feet. And that was the start of the romance.

Swent:

While you finished at Berkeley she was in Visalia, was she?

Wilson:

Bev taught in the little town of Pixley, taught elementary school. We were married in January of ’48, then we finished out the semester. Got the job with Bradley at the Yellow Pine Mine. And we reported up there to work I guess in July, just after the Fourth of July.

Swent:

Had you actually worked in a mine at all?

Wilson:

No, but I had been a surveyor, and when I got out of the army I was Tulare City Surveyor for a number of months before I went back to school. So really what they hired me to do was to be the surveyor for a new smelter construction we were doing. When that smelter was built, then I became a shift foreman at the smelter.

Wilson:

Prior to that time I worked for Bob Clarkson, who lives in Reno, good friend, talk to him two or three times a week.

Swent:

Developed Clarkson s, 1 some special machinery, didn't he?

Wilson:

That's right, he developed the Clarkson [reagent] feeder, and from then he left that mine and came to Palo Alto and started the Clarkson Company, building the feeders and building valves, and he moved his company to Reno. His son is now running the company, very successful slurry valve manufacturer. They still sell three or four hundred feeders every year, which is kind of neat.

Swent:

What was your degree in at Berkeley?

Wilson:

Extractive metallurgy.

Swent:

So you got away from your geology.

Wilson:

Yes, I don't really know why. I like chemistry and I was pretty good at chemistry and I think that's what got me into extractive metallurgy.

Swent:

But it was through Hulin that you got the job.

Wilson:

Then we became good friends after. Carl would always eat with us when he was up there on a consulting job.

Swent:

Did you have any summer jobs, or were you going to college?

John Robert Clarkson, Building the Clarkson Company, Making Reagent Feeders and Valves for the Mineral Industry. 1935 to 1998, Regional Oral History, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1999.

Wilson:

No, I just went straight through.

Swent:

So this was your first real mining job, at Bradley.

Wilson:

I think I did; no, I came back, I did. I was a surveyor. The summer of the first year I went back to Tulare and worked for an engineer, civil engineer, again surveying.

Swent:

But you had no smelter experience or anything like that.

Wilson:

No, I learned that on the fly.

Swent:

It's interesting; you built it, or you were in charge of building the smelter?

Wilson:

No, I was a surveyor, I laid out all the stuff, you know, and then I worked for Bob Clarkson and the chief engineer in the pit. Doing the engineering work, surveying.

Swent:

Oh, this was an open pit mine.

Wilson:

Yes, it was. Various construction projects were going on at that time.

Swent:

And then you became foreman of the smelter?

Wilson:

Yes, I was foreman, and then when I left I was assistant superintendent of the smelter.

Swent:

So you must have done some on-the-job training.

Wilson:

Oh yes, that's the kind of stuff you can't learn from textbooks.

Swent:

No. What did it involve?

Wilson:

We produced antimony oxide and gold bullion, and we shipped the gold bullion up to northern Idaho for treatment, another Bradley mine. The Bradley family started--

Swent:

Bunker Hill. Bunker Hill and Sullivan. So they had a refinery up there?

Wilson:

They did. This is an electric furnace smelting; we had multiple hearth roasters, in which we roasted the antimony concentrate which is stibnite, antimony sulfide, and roasted arsenopyrite, which contained the gold, and then combined the roasted product in the electric furnace, reduced the antimony to metal and in the process, the gold was absorbed with the antimony metal. So we came out with a gold bullion that was then concentrated by oxidizing the antimony, produce antimony oxide, leaving then the gold with some antimony metal.

Swent:

So gold will combine with antimony; I didn't know that. Was this a new smelter?

Wilson:

Yes, it was. The Yellow Pine Mine had operated during the war producing tungsten. It was the largest tungsten producer in the United States at that time. When I got there, in 1948, tungsten was just about depleted, and the demand for antimony oxide had increased by the defense department. They were using antimony oxide as some sort of paint to inhibit fires on naval vessels, that was the use of the stuff.

Swent:

So this was another deposit that was next to the tungsten deposit?

Wilson:

The scheelite--I don't recall the geology too well, but it seemed like the scheelite occurred almost adjacent to this stibnite arsenopyrite ore body.

Swent:

So they were able to continue mining something completely different. That's interesting.

Wilson:

It was a pretty large operation; there were about 1,200 people who lived in the town.

Swent:

The town was Yellow Pine?

Wilson:

No, the town was Stibnite.

Swent:

The town was Stibnite and the mine was the Yellow Pine Mine.

Wilson:

There was a village of Yellow Pine which is about fourteen miles down the river. First winter we were there the roads were snowed in. Ran out of food pretty close to it, and the Air National Guard dropped supplies to us, parachutes.

Swent:

Pretty exciting. And Bev taught school.

Wilson:

Bev taught school. Two of our children were born there. We left in late 51, November, December of 51. Harold Bailey had left Bradleys and joined Molybdenum Corporation of America, and he needed a mill superintendent, so he asked me to join him, I did.

Swent:

Were there any particular challenges to running a smelter?

Wilson:

Sure were. I’ll tell you all about them in the next episode. I had to deal with industrial health problems.

Swent:

Clean air was quite a problem?

Wilson:

Oh boy, everybody had perforated septums. I got heavy metal poisoning, damn near died, I’ll tell you all about that next time.

[Interview 2: July 9, 1996]

Swent:

This is continuing the interview with Alexander Wilson in Los Altos on July 9th, 1996.

Wilson:

What are we going to talk about?

Swent:

Well, let's talk about Stibnite. You didn't say anything yet about--. Where did you live? What sort of living accomodations did you have there?

Wilson:

The first summer we were there, Bev and I lived in the schoolteacher’s house in Yellow Pine.

Swent:

The company provided teachers, did they?

Wilson:

Well, we had a misunderstanding with the man who hired me, who was supposed to provide us a house. He did not; and we stayed in a little hotel in Yellow Pine. And the owner of the hotel was the head of the school district, so he took pity on us and let us move into the teacher s house. We lived there July, August, and I think we finally moved up to the mine in September.

Swent:

And where was this? In the town?

Wilson:

In the town of Yellow Pine, yes.

Swent:

And the mine was up the road a ways.

Wilson:

The mine was fourteen miles up the canyon from Yellow Pine.

Swent:

Stibnite was I'm trying to get this straight in my mind--Stibnite was down the-- [looking at map]

Wilson:

Well, you see the town of Yellow Pine.

Swent:

Right. And it's on a river.

Wilson:

Yes. East fork of the south fork of the Salmon River.

Swent:

The east fork of the south fork.

Wilson:

Yes.

Swent:

Okay. So the river is going west--?

Wilson:

Yes, right.

Swent:

--north.

Wilson:

Yes.

Swent:

So Stibnite is up--?

Wilson:

Yes. Up the canyon.

Swent:

Up the canyon. And the mine is in this area between the two?

Wilson:

Well, no. I think actually the mine is probably just right about where the dot is indicating the location of Stibnite. It's hard to tell from this map. The mine was just about two miles, a mile and a half, from the main town of Stibnite.

Swent:

So when you moved up to the mine, what sort of accomodations did you have?

Wilson:

Again, we lived in a teacher’s house. This was a house that had been constructed from two boxcars.

Swent:

What?!

Wilson:

Yes. Two bedrooms, one bath, small living room, kitchen with a wood stove.

Swent:

Were the boxcars side by side?

Wilson:

Beg your pardon?

Swent:

The boxcars-

Wilson:

I think they had, yes. It looked like a house by the time they got through with it. But fortunately, it was well insulated so we managed to live very well.

Swent:

Wood stove. No electricity?

Wilson:

There was electricity, but wood was plentiful and all it cost was the labor to go out and get it--cut it and bring it home.

Swent:

Bev hadn't been used to cooking on a wood stove.

Wilson:

No, but she did pretty well.

Swent:

You hadn't been used to chopping wood.

Wilson:

I guess that's right, yes.

Swent:

Did you learn?

Wilson:

Sure did. I learned a lot of things.

Swent:

You had to chop your own?

Wilson:

Yes. Yes. And I learned pretty quickly what wood to burn and what not to burn. So it was all very interesting and very exciting for a couple of young kids.

Swent:

What were you paid?

Wilson:

Three hundred and sixty dollars a month, we started.

Swent:

Did that include your housing?

Wilson:

I think we paid no rent, but I remember I was shocked at the first winter months we had. The house was heated with fuel oil; half my paycheck went to buy fuel oil the first months. But three hundred and sixty dollars a month wasn't bad in those days. It was in 1949.

Swent:

That was a lot. Did you have a car?

Wilson:

Yes. Good car. I had a Ford--Ford sedan: you know, one of those teardrop-looking things that Ford made, one of the early V-8s. I think it was of pre-war vintage.

Swent:

And Bev taught school?

Wilson:

Yes, she taught school.

Swent:

Right there? She didn't have far to go?

Wilson:

The schoolhouse was not far from where we lived, within walking distance. She taught second or third grades.

Swent:

Small classes, I suppose.

Wilson:

We should ask her about that, but I think she might have had twenty kids in the two classes.

Swent:

Did you come home for lunch?

Wilson:

Well, we had--. Hmm, I've forgotten some of these things. They served lunch at the mess hall in the boarding house. I think, for the most part, I had lunch there. I think they served lunch for something like fifty cents or twenty-five cents a day. They had a boarding house near the mill where the single men stayed.

I started work as a surveyor in the mine. There was a good deal of construction work going on: they were moving a crushing plant at that time. So that first summer I did the surveying for the crushing plant, and then did the work to keep the mine maps up to date.

Swent:

What sort of equipment were you using for surveying?

Wilson:

Well, transit and level, I suppose standard stuff for those days, nothing modern like the surveyors use today.

Swent:

Plane table?

Wilson:

I may have done some plane table work laying out haul roads, but most of it was transit work.

Swent:

What did you wear? What kind of clothes did you wear?

Wilson:

Well, that's an interesting question.

Swent:

That was before t-shirts and blue jeans, I think.

Wilson:

No, it wasn't before blue jeans.

Swent:

Well, yes, but before they were so popular.

Wilson:

I think I wore Levi’s—

Swent:

Did you? Or khakis?

Wilson:

I think I wore Levi’s when I was working in the mine and cotton work shirts. When I went to work in the smelter I wore khakis-- the cheapest I could buy. I think we bought them at Sears because they’d burn off me so often.

Swent:

Safety shoes? Safety hats?

Wilson:

Yes. We used hightop boots with the steel caps on the toes.

Swent:

Were they provided for you, or did you have to pay for them?

Wilson:

We had to buy them.

Swent:

Hard hats?

Wilson:

We wore hard hats in the mine.

Swent:

What were they made of?

Wilson:

I think fiberglass, I'm not sure. I suppose quite similar to the hard hats we wear today.

Swent:

They weren't as pretty. They didn't come in decorator colors in those days, did they?

Wilson:

No, they sure didn't. You know that. [laughs]

Swent:

Dark brown, weren't they?

Wilson:

I suppose.

Swent:

Safety glasses?

Wilson:

Yes, I wore safety glasses. Of course, I think that almost all the lenses that we wear today are what they used to call safety glasses: they’re plastic and don't shatter.

Swent:

Were you given safety training?

Wilson:

Yes, they did. But I'd had a mine rescue class when I was going to UC Berkeley. It seems to me that I may have taught the class in mine safety at Stibnite. I'm a little bit foggy on that.

Swent:

What about the Bradleys? Did you have any contact with them?

Wilson:

Quite a bit. The company was owned by the Bradley family and--

Swent:

Had you known them?

Wilson:

Jack Bradley was the family member who managed the mining activities for the family, so he was--

Swent:

Where did he live?

Wilson:

He lived in San Francisco.

Swent:

Had you met him?

Wilson:

No, I didn't know him.

Swent:

Did he come up to the mine?

Wilson:

He came quite often, yes. Shortly after I arrived, they began construction of the smelter, which was a significant investment for them and a departure for the mine. Up to that point, they were selling concentrate to a smelter in southern California. So I think Jack Bradley was there during summertime, often watching the progress of construction.

Swent:

Were you still there when the automobile accident happened? [Jack Bradley and his wife were killed in an automobile accident.]

Wilson:

Do you remember the year?

Swent:

No.

Wilson:

No, I don't either.

Swent:

It was--

Wilson:

I'm sure that by that time I was working for Utah.

Swent:

I was thinking it was about 1950 when they--

Wilson:

Do you think so?

Swent:

Maybe later.

Wilson:

Well, I don't know. But it occurred after I left, so it didn't matter. I left there in ’51.

Swent:

I was thinking of what the effect of that would have been on the company and on the mine.

Wilson:

Well, by that time, see, the mine was winding down and closed in 52--just the year after I left.

Swent:

Did they recoup their investment on the smelter?

Wilson:

I don't know; I doubt it. Because that smelter ran three, four years. I believe they began to operate it--could it have been the summer of ’49? I think probably so, ’50, ’51; it was shut down in ’52. Market conditions shut it down. There was still quite a bit of ore left in the pit.

Swent:

I want to talk about the smelter in a minute. But before we get to that, you mentioned flying up there with your friend Griswold, but then you also were a pilot, weren't you?

Wilson:

I learned to fly at Boise. In those days, the veterans of World War II were granted some money for education; and I had some left over when I graduated, so I applied that to flying lessons. I soloed in Boise.

Swent:

How far away is Boise?

Wilson:

I think it was right at a hundred miles by road. No, it's a hundred miles by air. I think it was almost a three-and-a-half or four-hour drive.

Swent:

So you would drive down there on your day off?

Wilson:

Well, we didn't get many days off. In the summertime, we worked twelve days and then had two days off.

Swent:

Eight-hour days?

Wilson:

Yes. The theory was you couldn’t go anyplace in one day, so you might as well put two weeks back-to-back and have two days to go no place.

Swent:

In the winter, this changed?

Wilson:

Boy, I'm really foggy on this.

Swent:

Most people worked a six-day week then.

Wilson:

I was on a six-day week. Whether we switched to a six-day week or did that twelve-on/two-off , I don't really remember.

Swent:

So how did you manage the flying lessons?

Wilson:

I didn't fly a heck of a lot. After I left and moved to California, little kids were coming along, and I really couldn't afford to fly, couldn't afford to rent an airplane.

Swent:

But you did get your license there.

Wilson:

Yes, I did. But it lapsed after I moved.

Swent:

Did you ever have your own airplane?

Wilson:

No. Years later, I did it all over again here in California.

Swent:

Let's talk about the smelter. You were smelter foreman, and then smelter superintendent. You were going to talk about some of the health problems at the smelter.

Wilson:

The industrial health hazards in smelters were not generally recognized in those days. Of course they knew that the fellows working around mercury would get heavy-metal poisoning, and those in the lead smelters, but it wasn't understood how all this came about. And the smelter in Stibnite, with the high arsenic content of the ore, there were just an awful lot of arsenic oxides floating around the atmosphere. let's see--.

Swent:

I was going to ask just a little bit about the mechanics of the smelter. You had a crusher and then ore going in--

Wilson:

Well, the smelter was on the tail end of the concentrator. First, you have the concentrator, where the ore--crushed at the pit, hauled by truck some two miles to the mill, to the concentrator- is ground and treated by flotation to separate the end product was two concentrates, arsenopyrite concentrate and an antimony concentrate. Those concentrates were then stockpiled, allowed to dry, and then conveyed from the stockpile to the roaster building.

Swent:

Were there hazards in the mill?

Wilson:

No, no, not at all. No industrial health problems. But once you got these arsenic sulphides and antimony sulphides in the roaster, then you began the oxidation process. As a result of that, you had arsenic oxide and antimony oxide filling the roaster building like a fog.

Swent:

They were roasted separately.

Wilson:

Yes, they were roasted separately.

Swent:

Two separate circuits? I guess you don't call it a circuit.

Wilson:

We had two large Herschoff roasters.

Swent:

And you are driving off the gases?

Wilson:

The mineral arsenopyrite is an iron arsenic sulphide, and stibnite is an antimony sulphide. The roasting process is to oxidize the sulphide, in order to provide a feed for the reduction furnace. The off gases from the roasters were ducted to a bag house, where the arsenic and antimony oxides were collected. Those oxides then made up part of the charge that went into the electric furnace.

Swent:

But there was leakage or escaping throughout the system.

Wilson:

Oh yes, but the bag house was the worst place. The roaster building and the bag house were the worst part of it.

Let me back up a little bit. I’ll go back through the process. The calcine concentrate from the roaster was combined with the oxides collected in the bag house, and charged into the electric furnace. So there was a great deal of metal oxide leakage out of the electric furnace--and that's where the antimony or the metal was tapped from the furnace. It contained from three to extreme conditions almost twenty percent arsenic. Arsenic was oxidized from the antimony in small reverberatory furnaces, using compressed air. The arsenic was once again oxidized. Although we had dust collection equipment, still there was an awful lot of that stuff floating around.

Swent:

Did you wear masks?

Wilson:

I think the operators who were operating the reverberatory furnaces wore some sort of breathing apparatus.

I don't think they were generally used in the smelter. Of course, that then led to a good deal of problems arising out of the heavy metal poisoning. First thing that went was the little division called the septum, the division between your nostrils. In extreme cases, the body absorbed the arsenic and antimony, and that affected the kidneys. That's where I got in trouble.

Wilson: