London's Electrified Subway

For almost 125 years, the City and South London Railway has operated in one shape or form, carrying passengers of the area to their destinations. Officially opened by Edward, Prince of Wales on November 4th, 1890, the City and South London Railway (C&SLR) began public operations on December 18th, 1890. The world’s first deep-level underground and electrified passenger railway, the C&SLR originally spanned six stations and across 3.2 miles in a pair of tunnels between City of London and Stockwell, passing beneath the River Thames.

After several extensions, major reconstruction, and a merger with another railway, the line today serves 22 stations over 13.4 miles from Camden Town to Kennington (Bank branch) and Kennington to Morden (Southern leg).

Parliamentary Beginnings

In November 1883, a private bill was sent to Parliament in regards to the construction of the CL&SS. Proposed by James Henry Greathead, the South African engineer who helped construct the Tower Subway from 1869-70, the CL&SS would be created through similar means as previously used—a tunneling shield method. Designed by Greathead, the method deviated from the “cut and cover” method used in other tunnel excavations, forcing steel blades mounted on a cylindrical apparatus into the soil by way of hydraulic rams (operating at pressures of 1575 tonnes per square meter). Proposed to run from Elephant and Castle (Southwark) and under the Thames to King William Street (London) the rail system would be comprised of two twin tunnels, each 3.1 meter in diameter, running 1.25 miles.

Having received Royal Assent on July 28, 1884, the railway proposal became the City of London Southwark Subway Act, 1884. In 1886, a proposal was made that extended the tunnels south from Elephant and Castle to Kennington and Stockwell and it received assent on July 12, 1887 as the CL&SS (Kennington Extensions, &c) Act, 1887. It extended the original route to 1.75 miles and allowed for slightly larger tunnels (3.2 to 3.5 m in diameter). A final bill was approved and published on July 25, 1890 as the City and South London Railway Act, 1890 (effectively changing the company name to City and South London Railway—C&SLR) which granted permission for the line to continue south to Clapham Common.

Haulage and Infrastructure

Supervising and leading construction of the railway system was Peter William Barlow, assisted by consulting engineers, Sir John Fowler and Sir Benjamin Baker, and in charge of the tunneling shield operations was James Henry Greathead.

With its small tunnels and lack of ventilation the C&SLR was originally intended to be cable-hauled since steam power was not a viable option. Similar to the cable-car system invented and used in San Francisco in 1873, the method originally intended for the C&SLR was patented and owned by the Patent Cable Tramway Corporation. The system would operate by way of a static engine pulling a cable through the tunnels at a steady speed and the train cars attaching and detaching at the stations; this allowed the system to operate without stopping the cable or interfering with the operations of other trains on the cable line. There were to be two independent, endless cables, on in each direction; one between City station and Elephant and Castle (10mph) and one between Elephant and Castle and Stockwell (12 mph). The practicality of the cable system was diminished by additional lengths of tunnel permitted by the acts.

The decision to use electricity to power the rail system was made when the cable contractor went bankrupt in January 1888 during the construction process. Having considered electrical motor operations for the railway, the company asked the Manchester firm, Mather & Plat, to provide the electric traction for the railway. Having secured the British manufacturing rights to Thomas Edison’s dynamo in 1883 and the design improved by Cambridge scientists John and Edward Hopkinson, the Edison-Hopkinson dynamos were used in the Stockwell power station, supplying electricity for fourteen locomotives that could travel at 40km/hr on 450V. The Stockwell depot and generating station, despite utilizing electric motive power, was originally illuminated by gas lamps. The station depot was above ground and a ramp was constructed to raise trains needing maintenance; later a lift was added to the station.

Five hundred volts of power was supplied to the railway system through the third rail beneath the train, allowing the train to pull several carriages at once. While electricity was used in previous train experiments and small-scale operations, C&SLR was the first major railway in the world to adopt it as a means of motive power.

Built below roadways to avoid the purchase agreements necessary to run beneath surface buildings, the railway was constrained in its construction methods, especially at the northern end near the River Thames and King William Street station. Rather than building the tunnels side by side, the close proximity to the river and narrow roadways necessitated that the tunnels maintain a steep incline to the west of the station, and be built one atop the other on the way to the station, converging into one large tunnel with a single track with platforms at either side as they approached the station.

Opening

On November 4, 1890 Edward, Prince of Wales conducted a formal opening ceremony for the C&SLR, switching on the electric current at Stockwell with a golden key. It was not until December 18 of the same year that public operations began. At its opening, the system had stations at Stockwell, the Oval, Kennington, Elephant & Castle, Borough, and King William Street.

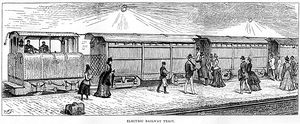

Each train engine originally hauled three carriages lit by electricity, nicknamed “padded cells” because of their small size, allowing for thirty-two passengers per carriage. The carriages possessed longitudinal benches, sliding doors at either end, and outer platforms to assist with boarding and disembarking with the station. Because the tunnels lacked scenery, the carriages had only a narrow band of windows located at the tops of the carriage sides.

Unlike other rail systems, the C&SLR did not initially have class car system or paper tickets. Operations began at a uniform flat rate of two pence a ride collected at the turnstile prior to boarding. In its first year of operation (1891), the railway served 5.1 million passengers. In order to alleviate overcrowding, the system was expanded to include more trains and extensions were made to the existing lines.

Extensions

Over the history of the C&SLR system, several extensions were made to the lines. On February 25, 1900 the first section of the northern extension starting at King William Street station was opened, including new stations at London Bridge, Bank, and Moorgate Street. On June 3rd of the same year, the southern extension at Clapham Common was opened with stations at Clapham North and Clapham Common. These new additions constructed the stations with a single tunnel and a central platform with tracks on either side. The second section of the northern extension was approved on May 25, 1900 as the City and South London Railway Act, 1900 and opened on November 17, 1901 with stations at Old Street, City Road, and Angel which included an enlarged station tunnel (9.2 m).

From 1901 to 1907, the C&SLR, due to the lack of profits and several extensions proposed and constructed, suffered a financial strain. In order to encourage funding, the Euston extension was proposed by a separate company (Islington and Euston Railway, I&ER) who shared its chairman with the C&SLR. Running from Angel to King’s Cross, St. Pancras and Euston, the proposed extension suffered a series of oppositions before receiving assent on August 11th, 1903. Although many of the proposals of the bill were never implemented, the extension was built and opened on May 12, 1907 including stations at King’s Cross St Pancras and Euston.

Cooperation, Mergers, and Reconstruction

By 1907 the underground railway had expanded from the original six stations to a network of seven lines and more than 70 stations. Despite major expansion, competition between railways and with electric trams and motor buses greatly reduced the underground system’s revenues. In 1907, in order to alleviate the collective financial state of the railway systems, most of London underground railways (C&SLR, CLR, Great Northern & City Railway, and the Underground Electric Railways Company of London) introduced fare agreements. The arrangement led to the common branding of the railway system as the “Underground” in 1908. The only tube railway that did not participate in the agreement was the Waterloo & City Railway, operated by London and South Western Railway.

C&SLR proposed a bill in 1912 which sought to increase its capacity by enlarging the tunnels to allow for the larger, modern stock to be used. At the same time, the London Electric Railway proposed plans to construct tunnels which would connect the C&SLR at Euston to the CCE&HE’s Camden Town station; this would essentially join the two separate railway systems. On January 1, 1913 the UERL bought the C&SLR for a rate of two shares of its own stock for three of the C&SLR’s. Both of the previous bills were enacted on August 15, 1912 but the extension and tunnel reconstruction was delayed by World War I.

Following the end of the war, the extensions and reconstruction was further delayed by lack of funds; the projects were only made possible by the passing of the Trade Facilities Act, 1921 which allowed for government loans for public works in order to reduce unemployment rates. The tunnels were enlarged by removing segments of each tunnel and excavating behind them to increase the diameter and reinstalling the segments. The reconstruction led to the temporary closing of some of the tunnels, until April 20th, 1924 when the Euston Moorgate section reopened with new tunnels linking Euston and Camden Town. The rest of the Clapham Common line reopened on December 1, 1924.

Other reconstruction efforts led to modernization of the stations, with longer platforms, new tiling and building fronts, and, in some cases, the addition of escalators in place of the lifts. Additionally, following the passing of the City and South London Railway Act, 1923 on August 2, 1923, an extension was made at Modern which opened on September 13th, 1926 with stations at Clapham South, Balham, Tooting Bec, Tooting Broadway, Colliers Wood, South Wimbledon, and Morden. The combined operations of CCE&HR and C&SLR were further strengthened by the opening of tunnels which connected CCE&HR’s Charing Cross station and C&SLR’s Kennington station via an intermediate Waterloo station. This merger formed a single London Underground line, renamed the Northern line in 1937.

Public Ownership

While the C&SLR underwent reconstruction and constructed several new extensions to the system in order to increase revenue, the Underground railway system as a whole continued to struggle to make a profit. The Underground was able to subsidize the railways with profits from the London General Omnibus Company since 1912, but with competition from other bus companies this ability diminished. In order to protect the Underground Group, Managing Director and Chairman Lord Ashfield lobbied for government regulation of the London transportation services. In the 1920s several legislations were pursued but it was not until the end of the 1930s that the bill was announced which would form the London Passenger Transport Board, a public corporation that would assume and manage all of the Underground Group, the Metropolitan Railway, and all buses and trams within a given area. Thus the Board, coming into existence on July 1, 1933, liquidated the C&SLR and other railways and moved them into public ownership.

Engines and Carriages

Throughout the C&SLR's history, the companies and builders that produced the locomotives and carriages have changed with new technological developments and funding changes.

| Engines | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Built | Numbers | Builder | |||

| 1889-1990 | 1-14 | Mather & Platt | |||

| 1891 | 15-26 | Siemens Brothers | |||

| 1897-98 | 17 | C&SL Stockwell Works | |||

| 1987-98 | 18 | Crompton & Co | |||

| 1897-98 | 19 | Electric Construction Co. | |||

| 1897-98 | 20 | Thames Ironworks | |||

| 1899 | 21 | C&SL Stockwell Works | |||

| 1900 | 22 | C&SL Stockwell Works | |||

| 1899 | 23-32 | Crompton & Co | |||

| 1900 | 33-42 | Crompton & Co | |||

| 1901 | 43-52 | Crompton & Co | |||

| Carriages | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Built | Numbers | Builder | |||

| 1889-90 | 1-30 | Ashbury Carriage & Iron | |||

| 1891 | 31-36 | G F Milnes & Co | |||

| 1894 | 37-39 | Bristol Wagon & Carriage Works | |||

| 1896 | 40-46 | Oldbury Carriage & Wagon Co | |||

| 1897 | 47-54 | G F Milnes & Co | |||

| 1899 | 55-84 | Hurst Nelson & Co | |||

| 1901 | 85-108 | G F Milnes & Co | |||

| 1901 | 109-124 | Bristol Carriage & Wagon Co | |||

| 1902 | 125-132 | G F Milnes & Co | |||

| 1907 | 133-165 | Brush Electrical Engineering, Co | |||

Legacy

The C&SLR demonstrated the potential of deep tube tunnels and electric traction in transportation methods and influenced the subsequent construction of underground railways. Within a decade of the opening of City and South London, two more lines were constructed (Waterloo and City and the Central). Other lines opened in Budapest (1896, first of the continent), in Boston (1897, first in North America), and Paris (1900, first of the Paris Métro). By 1936, many other cities had established subway systems: Glasgow, Philadelphia, Madrid, Barcelona, Buenos Aires, Tokyo, Sydney, Osaka, Berlin, and Moscow.

The C&SLR proved the possibility of constructing deep level tunnels without surface disruptions and encouraged the development of London’s network of underground railways and tunnels, forever influencing public transportation methods. Today the tunnels and stations of the C&SLR form the Bank branch of the Northern line from Camden Town to Kennington and the southern leg of the line from Kennington to Morden. As a whole the Northern line served over 200 million passengers in 2011 and 2012, making it the second busiest line on the Underground.

Bibliography

"City & South London Railway." Engineering Timelines. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 Mar. 2015. <http://www.engineering-timelines.com/scripts/engineeringItem.asp?id=1030>.

"City and South London Railway." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 24 Feb. 2015. Web. 03 Mar. 2015. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/City_and_South_London_Railway>.

Nebeker, Frederik. "Electrifying Transportation: Streetcars and Subways." Dawn of the Electronic Age: Electrical Technologies in the Shaping of the Modern World, 1914 to 1945. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE, 2009. 206-07. Print. The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. "London Underground." Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., 24 Apr. 2013. Web. 3 Mar. 2015. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/1300656/London-Underground>.

"A Brief History of the Underground." Transport for London. TfL, n.d. Web. 03 Mar. 2015. <http://www.tfl.gov.uk/corporate/about-tfl/culture-and-heritage/londons-transport-a-history/london-underground/a-brief-history-of-the-underground>.

See also: Straphanger History: Pre-Subway Transportation, Mechanization of Urban Transit in the US