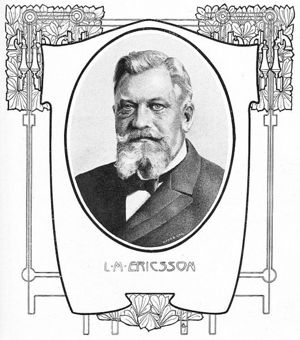

Lars Magnus Ericsson

- Birthdate

- 1846/05/05

- Birthplace

- Varmland, Sweden

- Death date

- 1926/12/17

- Associated organizations

- Siemens, Oller & Co, L.M. Ericsson & Co

- Fields of study

- Telephony

Biography

Great enterprises, a noted philosopher once suggested, are lengthened shadows of great men. During the past century thousands of outstanding men and women have contributed to the Ericsson Group of telecommunication companies. But the imprint of Lars Magnus Ericsson, who founded the enterprise in 1876, is still unmistakable.

The man who was to give his name to one of the great multinational industrial enterprises of the twentieth century first saw the light of day on May 5, 1846, on a small farm in the Province of Varmland in the middle of Sweden. The nearest village was Wergerbol, in Varmsgog Parish.

Lars Magnus Ericsson was not autobiographical by nature and few details of his childhood years have sifted down to the present. Most of what is known of this period is contained in a letter written to a son when Ericsson was already nearing 70.

The "first serious blow" in his life came, he says, at the age of eleven with the sudden death of his "God-fearing and respected father." Two elder brothers had already abandoned the family farm to earn their living and young Ericsson was left at home with his mother and two younger sisters. Regular school attendance was not required in those days but there is evidence that the boy attended the relatively primitive local schools and "took lessons from the parson" until his 14th year, when he became a day laborer on a neighbourhood farm.

Ericsson was a frail youth and soon discovered that he had neither the disposition nor strength for farm work. But he recalled that his life was "spiritually rich" and that his determination was fortified "to meet future destiny, honestly and trusting in God."

His first step toward "destiny" came the following year. A mine overseer who had been a good friend of his father, was assembling a work crew to investigate more deposits in the Egersund region of Norway. Ericsson pleaded to go along and was finally accepted. His first job was to carry drills from the smith's shack to the blasting sites, and to help at the forge.

"When we had been there about half a year," Ericsson recalled later, "it happened that the smithy got a yearning for the town and stayed there longer than he should have. While he was away I carried on with the drills. And all were so satisfied with their sharpness that, shortly after, I was entrusted with the work of the smithy. This led to an improvement in my pay, so that I was able to send quite appreciable amounts to those at home who were existing there in poverty, being able to earn nothing."

Ericsson worked on various mining projects, and on a railway construction job, for the next several years, but he had broader horizons.

"Deep down," he wrote, "there smouldered an ever stronger desire to learn a trade, preferably in the mechanical branch." He had been able to put aside a little money and now he sought to apprentice himself to an art-metal smith. His first connection was in the village of Grafas but the man was old, infirm and seldom able to work and soon referred his young assistant another smith, Nils Andersson in Heljeboda. This shop was equipped for water power and there, for the first time, Ericsson saw a slide lathe.

Andersson could not make a go of things, however, and decided to take a job as head of the nail manufacturing department of the Charlottenberg Works which even in those days employed special machinery. In his contract, Andersson specified that Ericsson should accompany him as his apprentice.

During the next two years, which he described as "years of learning," Ericsson recorded that he had to "work like a dog."

"I received no more than the minimum of food and rest in a dirty smithy room," he remembered nearly 50 years later. "Everything else I had to get as best as I could and I took up the engraving of seals, for which there was a gratifying demand, in my leisure time."

Finally the young man had accumulated enough capital to enable him to take the first big step toward a career that would establish him as one of Sweden's industrial giants. He journeyed to Stockholm, where, after a week's trial, he was hired at the Oller & Company Telegraph Factory. The wages were only five kronor per week. They were, Ericsson recalled later, "sufficient for my needs, so that I thankfully saw life much brighter than ever before and felt then the first breath of the joy of life in my heart." The year was 1867.

Oller's workshop, the first in the electromechanical industry in Sweden, had been established in 1857 by A.H. Oller, the director of telegraphs, to manufacture telegraph instruments and other equipment for telegraph stations. Ericsson worked there for six years, acquiring a reputation as a particularly industrious and skilful instrument maker. In his spare time he studied draftsmanship and languages - primarily German and English - and in various ways prepared himself for further study abroad.

His Training Abroad

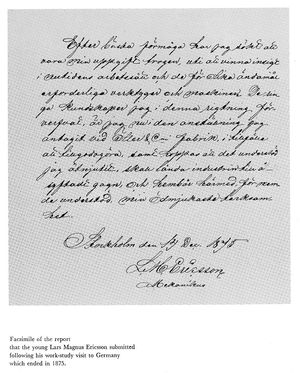

The Swedish Government was one of the first in the world of offer promising young workers and students grants for travel and study in other countries. Ericsson received two such grants in 1873 and 1875, both times on Oller's recommendation. They were to prove decisive elements in his career. From the brief report he submitted in December, 1875, following his return to Stockholm, it is possible to discern the outlines of two and a half years of work, study and observation in German and Swiss factories.

Here are some excerpts: "In Berlin my first engagement was at Siemens & Halske's factory, where, in the course of 11 months, by working in different departments, was able to acquire knowledge both of the methods of working and the different telegraph instruments manufactured there."

"I also worked in Berlin at Lud. Loewe & Co.'s factory, where I was able to learn something of the advantages of the American machine tools."

"Moreover at Kernaull's scrap metal factory, where I also worked, I found much that had hitherto been unknown to me and which was of interest to observe, as was the case at A Ronsack's workshops for mathematical instruments... Moreover I have worked in Munich at the physics institution of Prof. Dr. Ph. Carl and in Berne with the firm of Hasler & Escher, where I was employed on the assembly and adjustment of self-recording thermohygrometers, designed by Prof. Wild. In Neuchatel, Strasburg and Karlsruhe I have either been employed at, or visited, the best known plants."

"Recently I was employed at Schaffer & Buddenberg's factory in Buckau Magdeburg, where my chief work was the assembly and adjustment of indicators, but I was also able to devote attention to the distribution of work, machine tools and equipment for special purposes."

The concluding paragraph is, in one respect at least, highly prophetic.

"To the best of my ability I have tried to carry out my mission faithfully by obtaining an insight into presentday methods of working and into the tools and machines required for this purpose. I now have occasion to make use of the modest knowledge I have acquired in the position I have taken in Oller & Co.'s factory and I trust that the grant I have enjoyed will prove to the anticipated advantage of the country's industry, and I hereby express my humble thanks for the said grant."

Few grants of this type have probably paid off so well for the country's industry. Although he had returned to Oller's following his travels abroad, Ericsson was now ready to strike out on his own. This he did less than four months after submitting his report.

The Company is Born

In April 1876, Lars Magnus Ericsson opened an electro-mechanical workshop in a rented kitchen at Drottninggatan 15 in Stockholm.

Those who were familiar with Ericsson's cautious and deliberate approach to major projects have concluded that the project must have been on his mind for some time.

His physical assets were meagre, consisting primarily of an instrument maker's pedal lathe.

His working capital was 1,000 kronor, borrowed from a Mrs. Maria Stromberg of Nygard, who must certainly qualify as one of the most perceptive Swedish investors of the century. His labor force was a single twelve-year-old assistant.

But, as Hemming Johansson has written: "Enormous capacity for work, tough energy, remarkable skill in the trade and extensive experience in the field he had made his own - combined with honesty and prudence in business matters - were the foundation stones on which Ericsson could base his activity." They proved to be quite adequate assets.

In America, Alexander Graham Bell had just received his first patents on the telephone. A great new era in communications was about to open.

In the beginning Ericsson was engaged mainly in the repair of telegraph instruments and other electrical devices. But he soon began to produce improved equipment of his own design. A notable example was a dial telegraph instrument for use in railway systems. He also designed a fire telegraph system for small communities that became the prototype of systems used at home and abroad for many decades.

Ericsson's reputation for quality work soon enabled him to obtain orders from a wide variety of public and private authorities in such fields as telegraphy, fire protection, police administration and rail transportation. Various companies within the Ericsson Group continue to function as suppliers in these peripheral fields of telecommunications.

Not long after opening his workshop Ericsson brought in a former workmate from Oller's, Carl Johan Andersson, as his first and only partner. Andersson, who had also studied abroad with the assistance of Government grants, contributed 1,000 kronor to the enterprise which now became known formally as L.M. Ericsson & Co. Andersson continued as Ericsson's closest associate for many years, even after the partnership was later dissolved and the founder regained complete financial control.

Two significant events in Ericsson's life occurred in 1878. At the age of 32, he married Hilda Simonsson who became not only the mistress of his home but also an active colleague in business. For a number of years the winding of electromagnet reels with silk-insulated copper wire was entrusted to Mrs. Ericsson, at first working alone and later with the help of one or more assistants. It is said that even when confined to bed, Mrs. Ericsson continued her work with the winding machine propped on her knees. And Hemming Johansson reminds us that, in other matters also, Ericsson "benefitted by his wife's practical mind and wise counsel."

The second major event of 1878 was the delivery, during the month of November, of the first telephones of Ericsson's manufacture. American made instruments had been introduced in Sweden the previous year and some of them had already been in Ericsson's shop for repair. The experience thus gained, coupled with the studies Ericsson had undertaken after reading news accounts of Bell's invention, had enabled him to design and produce "serviceable" instruments.

Other orders followed in close succession and, although the telephone continued to be regarded as a luxury, Ericsson intensified his efforts to improve his instruments and related equipment.

The "breakthrough" of telephony in Sweden occurred in 1880 when the American Bell Company, using American equipment, constructed the first telephone networks in Stockholm, Gothenburg, Malmo, Sundsvall and Soderhamn. The situation was critical for Ericsson. He stood to lose virtually all of his home market unless he and Andersson could demonstrate convincingly that their equipment was equal, if not superior to that of Bell's.

The showdown came the following year - 1881 - when the city of Gavle', on the Baltic coast, called for bids to supply a local telephone system. The Bell Company in Stockholm offered to install and operate a system for 200 kronor per subscriber per year, based on a minimum of 50 five-year subscriber contracts.

At this point a local entrepreneur entered the picture. Relying on Ericsson's engineering and price estimates, he offered to install the system for 275 kronor per subscriber and thereafter to operate it for 56 kronor per subscriber per year. At the end of January instruments from Bell and Ericsson were set up in Gavle for comparative testing. The testers certified that both functioned very well but that they considered Ericsson's telephones "simpler, stronger and more attractive."

The Gavle Exchange Association, which had responsibility for the final decision, nevertheless decided to call in a new jury of two telegraph experts and one technician. On February 15 the new inspectors reported Ericsson's telephone "to be better made, provided with a better ringing device and with a better designed and movable microphone..." Ten days later the bid on behalf of Ericsson's equipment was accepted with only minor modifications.

The victory over Bell at Gavle and later the same year at Bergen, Norway, were major milestones in the development of Ericsson's five-year-old enterprise. He had demonstrated that Swedish craftsmanship and Swedish technique could hold an equal footing with those of the largest company in the field. He had established a firm position in his home market and he had opened up the first long succession of markets outside Sweden. Both were momentous achievements.

Building an Industry

At the beginning of 1880 Ericsson had 10 workmen on his payroll. Four years later the number was close to 100. The dynamic growth of the enterprise which was to continue - with few setbacks - for nearly a century was under way. Personal details of Ericsson's life during the quarter of a century prior to his retirement are scarce. The company was his life and he apparently had no time or inclination for outside interests or diversions.

These were the years when Ericsson's great energy and capacity for work were most productive. Hemming Johansson, recalling Ericsson when the latter was in his fifties, writes:

"The amount of work he could perform was incredible. Often he brought with him in the morning at the opening of the office a sketch or a drawing of a design that he had worked out the previous evening or night, or that he had put on paper during the boat trip into town. The whole day long he was occupied with organizing and supervising the work out in the plant, interested in the slightest details, with interruptions for discussions of business matters in the office and for participation in, and supervision of, the work of the drawing office. 'Standard working day' was, and always had been, an unknown concept for Ericsson. The close of regular working hours signified most often for him merely that he returned to his beloved drawing board, where, undisturbed, he could devote himself to his favorite occupation. Or maybe trials and experiments with new instruments and equipment took up a great part of the hours the others reserved for entertainment and rest."

These were also the years of Ericsson's close relationships with Henrik Tore Torston Cedergren and the Sievert brothers, Max and Ernst - relationships that were to play a significant role in the development of the new telephone manufacturing company and the Swedish telephone industry.

Henrik Tore Cedergren is regarded by many as the first Swede to appreciate the potential of the telephone if it could be made available to the general public at reasonable cost. In his opinion, the rates charged by the Swedish Bell companies were almost prohibitive. In 1883, to carry out his vision of "a telephone in each home in Stockholm, to begin with," he formed Stockholms Allmanna Telefonaktiebolag (Stockholm Public Telephone Company), relying on Ericsson to design and produce the quality equipment he would need in order to compete effectively with the Bell companies.

Initially Ericsson, cautious by nature, is said to have been cool to the venture. He knew that neither Cedergren, an engineer, nor any of his proposed associates had any technical of financial experience in the field of telophony. Cedergren's enthusiasm finally prevailed, however, and a collaboration of inestimable value to the future of telophony in Sweden was established. Thirty-five years later, in 1918, SAT would be merged into L.M. Ericsson Telephone Company when the later was restructured.

In 1888, Ericsson provided the principal support for the formation of Sieverts Kabelverk, formed in the Stockholm suburb of Sundbyberg to produce covered copper wire. Max Sievert had for a number of years represented a foreign manufacture of this type of wire, which was increasingly important in Ericsson's production program. The Sieverts company, now the largest producer of cables in Northern Europe, is today a subsidiary of the Ericsson Group.

As demand for the new Company's products increased, Ericsson continued to be responsible for a number of pioneering developments. While these were a natural consequence of his technical insight and his skill as a designer, Ericsson is not usually ranked among the great inventors. As Hemming Johansson has pointed out: "In his eyes, an invention was not an end in itself but only a means. His inventions may be said to represent stages in a constantly proceeding energetic effort to develop and improve the branch of electrotechnique to which he had devoted himself."

One of Ericsson's important contributions was to give telephone instruments and their important components a light, attractive appearance without any impairment of technical performance. In this respect, Ericsson instruments differed substantially from the early equipment offered by other manufacturers. Ericsson's first transmitter, the so-called "spiral microphone" developed in 1880, was an original and ingenious design which greatly facilitated the spread of telephone service in Scandinavia prior to the introduction of the carbon transmitter.

It was Ericsson who provided the practical design and engineering for the first hand sets which combined receiver and transmitter in a single unit. While the concept is not regarded as his invention, he is credited with recognizing its value and with establishing the new-style instrument in world markets.

Similarly, Ericsson contributed substantially to the design of early telephone exchanges, designing and producing the first "multiple desk" in Europe in 1884. With Cedergren, he is also credited with developing several automatic connecting switchboards, which enabled Stockholms Allmanna Telefonaktiebolag to offer unusually low subscriber rates when it began operations in 1883. Many of these switchboards continued to be used for more than half a century.

In the concluding years of his business life Ericsson participated actively in the design and engineering of the then new central battery system.

Hemming Johansson notes:

"As a designer, as in other respects, Ericsson was a self-made man... he was a genius in that sphere, and a genius is not created by study. Persons observing Ericsson's way of working gained the impression that the design was definite and complete in his inner mind before he gave it form on paper, so rapid and sure was the procedure. His work at the drawing board was lightened to a degree by Ericsson's thorough knowledge of his trade... he could visualize to the last detail how the instrument engaging his thoughts for the moment should be built up so that it could be produced in the most sample and efficient manner."

One of Ericsson's major contributions to telephony was his continuing insistence on product quality. His standards were higher than those then considered necessary by foreign competitors, who were gradually forced to raise their sights. The solid quality of Ericsson's work and the elegance of his designs established his products as symbols of the finest in telephony.

By the mid-nineties Ericsson's company had approximately 500 employees - a relatively large number in those days in nearly all countries - and was firmly established in both domestic and export markets. The Company had customers throughout the world, the bulk of them located in the Scandinavian countries, Russia, England and the countries than today comprise the British Commonwealth. Export sales consistently exceeded sales in the limited Swedish market and in some years accounted from 70 to 85 percent of invoicing.

In 1896 Ericsson transferred the business of L.M. Ericsson & Co., to a new corporation, Aktiebolaget L.M. Ericsson & Co., capitalized at one million kronor. Ericsson owned all the shares except for a number distributed as gifts to the faithful Carl Johan Anderson, his works manager for many years, and to 31 other key employees.

Ericsson served as managing director and chairman of the board of the new corporation for four years, retiring as managing director in the fall of 1900. He continued as board chairman, displaying an active interest in the company, until 1903, when disposed of his shareholdings and served all formal connections with the enterprise he had founded and guided to a position of international stature.

Retirement

When Lars Magnus Ericsson left the company in 1903, he was still only 57 years old and in the full prime of life. It appears that he had no desire to sink into an existence of passive leisure but wished to apply his energies to farming, an avocation in which he had been interested since the purchase of his estate at Ahlby, near Stockholm, in 1896.

He plunged actively into his new venture, making substantial investments in his property with the objective of making it more productive. He also found time to indulge one of his earliest and permanent loves, designing.

Ericsson continued to run Ahlby until 1916. Hemming Johansson recalls that "he was by no means a hermit. There, as host, he displayed the greatest hospitality and amiability and his pleasure in welcoming friends of various classes was great and unfeigned. On such occasions he could give free rein to gay spirits and let his sense of humor come into play without the restraint which he might have thought should be maintained during work hours."

When he turned Ahlby over to his youngest son, Ericsson moved to a neighbouring farm at Hagelby, applying much of the knowledge and experience acquired on his first estate.

As the years advanced, however, his sight began to fail, first depriving him of the pleasure he had always found at his drawing board and later forcing him to give up reading. In his last years his continuing thirst for news and knowledge could be satisfied only by having someone read to him.

On December 17, 1926, in his 81st year, Lars Magnus Ericsson passed away. Five days later his remains were laid to rest in the ancient cemetery of Hågelby gård in Botkyrka, not far from Stockholm. In accordance with his wishes, there were no eulogies and no commemorative stone marks his burial spot in the small churchyard.

In 1946, however, on the centenary of Ericsson's birth, a simple but impressive marker was erected in the churchyard of his native parish, Varmskog. The brief but eloquent inscription reads: "The Swedish Telephone Industry Bears Witness to His Achievements."

About Ericsson the man

As the inscription on the Varmskog marker suggests, Ericsson was content to be known by his works. He did not seek personal recognition and, in fact, avoided it whenever possible. When Stockholm University in 1909 wished to confer on him the prestigious degree of honorary doctor of philosophy, he declined respectfully, citing his "lack of qualification for the honorable distinction..."

Perhaps the best glimpses of Ericsson as an individual are contained in the brief biographical sketch prepared by Hemming Johannson in 1946.

"His outer appearance was impressive, his attitude unassuming but marked by ingrained grandeur and dignity, his utterances were always well considered, wise and logical," Johansson writes.

Johansson leaves no doubt that Ericsson inspired both respect and fear in many who approached him for the first time. But he adds that this reaction yielded to an affection that grew in strength when one found "that beneath the apparently cold exterior there were concealed a warm heart and a sterling character."

According to Johansson, Ericsson possessed great ability for directing his subordinates:

"His orders were often garbed in the soft folds of wishes, without thereby losing anything of their force. His temperament was even and the writer cannot recall a single example of Ericsson forgetting himself even under difficult and exacting situations... If he had reason for displeasure, this found its expression in biting sarcasm and reflections which, though pointed, were politely expressed, all of which possibly had a greater effect on the victim than if the correction had consisted of invective."

Ericsson's authority over his workers was based both on his recognized knowledge of workshop practice and on his "genial and unaffected" manner of dealing with them. Johansson says the workers looked up to Ericsson, had warm affection for him and tried to do their best to please him. "It was a kind of patriarchal relation, a mutual trustful cooperation..."

Many who dealt with Ericsson considered him a pronounced pessimist. Johansson prefers to characterize him as cautious, although he concedes that Ericsson probably had no "prophetic vision" of the future development of telephony.

In Ericsson's business, the term "speculation" had no part, Johansson records. But he describes his friend as being able to make quick decisions involving appreciable sums of money "when a desirable goal was to be gained..."

"For my part," Johansson writes, "I cherish the opinion that Ericsson was basically optimistic. Extremely cautious he was, but between pessimism and caution there is a wide gulf. His energy and capacity for work, his intense love of work and his conduct in daily life were not the characteristics of a pessimist."

References:

"Lars Magnus Ericsson, A Brief Biography", Telefonktiebolaget LM Ericsson. Permission to use extracts from Mr Mats Dahlin. This 36 page booklet (English version circa mid 1950’s) is based largely on a Swedish manuscript by Hemming Johansson in the Ericsson Review #2, 1946, a business associate and personal friend to Lars Magnus Ericsson for more than three decades.

http://www.ericssonhistory.com/templates/Ericsson/EricssonBook/Chapter.aspx?id=3164&epslanguage=EN