First-Hand:The Story of the Automobile Voltage Regulator

Submitted by Bernard Cain

When I was a youngster in grade school we had a little ditty that went:

Gene, Gene, Made a machine,

Joe, joe, Made it go,

Frank, Frank, Turned the crank

And sent it over the sand bank.

We really didn't know what this meant, but it clearly had something to do with people who made gadgets.

My talk today is about people who helped develop a machine, which we all use, our modern automobile.

There have, of course, been many names names associated with the development of the automobile. But here are some you never heard about in that connection, although I'm sure some of you knew these men.

One was Karl Pauly. He was head of Industrial Engineering for General Electric in the 1930s. Karl Pauly was a brilliant engineer who, among other things, published a book explaining his theory of the causes of the World's great Ice Ages.

Another was Max Whiting. Never a manager himself, he was one of Karl Pauly's most capable engineers. He was of the old school, before the influx of young engineers trained in Bob Dougherty's Advanced Course in Engineering. Max was a brilliant engineer and a prolific inventor.

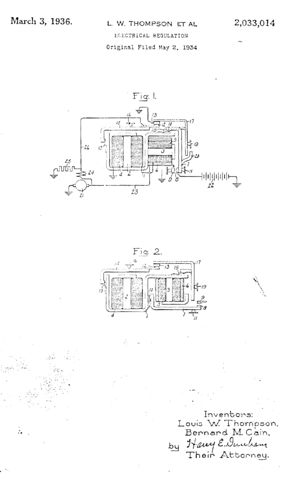

Louis Thompson was in a different operation of General Electric. He was a deSigner of voltage regulators and regulating systems. He too was a prolific inventor with many patents.

These names are the forefront of my story, but there were others.

Not long ago you heard the story of the Auburn museum in Indiana and the remarkable Duesenberg automobile. Today we have another automobile story. It will be interesting for two reasons. One reason is that I played an important part in this story as did other local people, some of whom I have just mentioned. Another reason is that, although you have lived with the automobile for many years, you will learn some things about it that few, if any, of you are familiar with. But after we finish I think you will understand them better.

The modern automobile is a model of dependability. We step out of our homes at any hour of the day or night, in any kind of weather summer or winter, we turn the key. Immediately the engine goes into action and we are off to whatever mission we plan. Few drivers today recall the hand crank era of the teens, or the problems of the early aware of the history of developments which brought electric starting to its present state of dependable performance.

The electric starter was the brainchild of no less genious than Charles F. Kettering, famed inventor and for many years head of research for General Motors Corporation. Electric starting was first introduced by Cadillac in 1911. Ford probably the last to replace the hand crank with the electric starter in the early 20's.

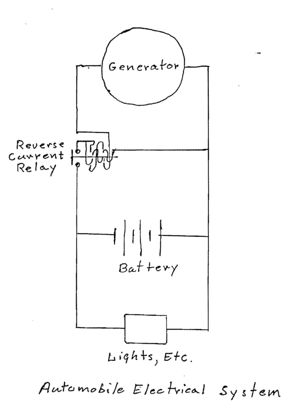

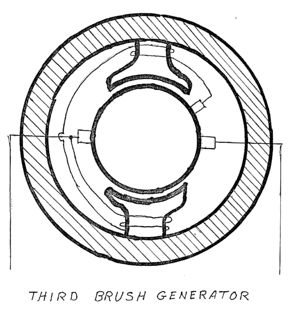

Kettering's early concept of the electric system was a single unit doing double duty as starter and generator, the function of the generator being to keep the storage battery charged. Dodge Brothers used this system for many years. However the system which had become standard on almost all cars by the late teens or early 20's was a starting motor, geared to the flywheel during starting by a self engaging and disengaging Bendix gear, and a separate belt driven generator. The generator was a self regulating "thurd brush" type unit which, after cut-in, produced nominally constant current regardless of car speed.

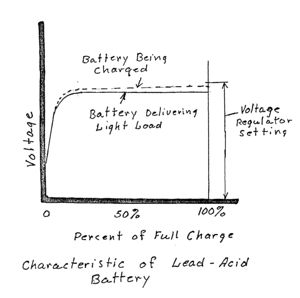

The third brush, constant current generator dominated the automobile industry for more than 20 years, until about 1936. It had many problems. For example in summer when driving on long trips the well informed driver would keep his lights on to avoid overcharging his batter. But the majority of drivers simply allowed battery life to be destroyed overcharging. The life of a battery was two years, if you were lucky. In winter there was a worse problem. Trips were much shorter and there was more need for headlights. The generator had a hard time keeping up with battery needs. Dead batteries on cold winter mornings were a common occurrence.

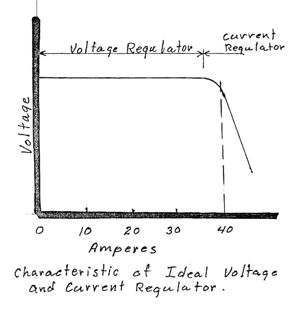

In the early 30's car heaters and radios were introduced which brought added load to the electrical system. It was then that Karl Pauly, head of Industrial Engineering for the General Electric Company, and Max Whiting, one of Pauly's leading engineers, reasoned that there had to be a better way of charging the automobile storage battery. Constant voltage with current regulation, not constant current had to be the solution. Such a charging system would automatically adjust to the battery's needs and also would cause the generator to carry such loads as headlights, heaters and radio, instead of their being a drain on the battery. Not only was constant voltage better for the battery but a voltage regulated generator could be designed to give about twice the output at no increase in cost to manufacture.

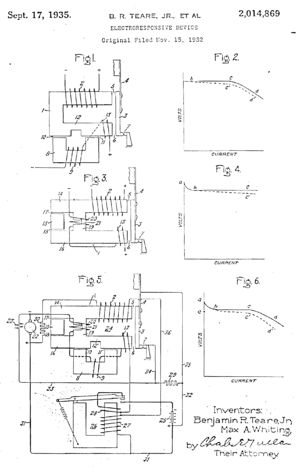

In the 20's and 30's the automobile business had already become highly competitive. Introduction of a voltage regulating system even though it benefitted the user, had to be done with a cost reduction if possible. Max Whiting and Richard Teare, a young engineer in training, together invented a simple regulator, US patent 2014689 which combined voltage and current controls to make a simple and hopefully low cost device. This regulator offered hope of interesting the automobile manufacturers. But General Motors and Ford were already making their own electrical equipment. Chrysler's was supplied by the Autolite Company.

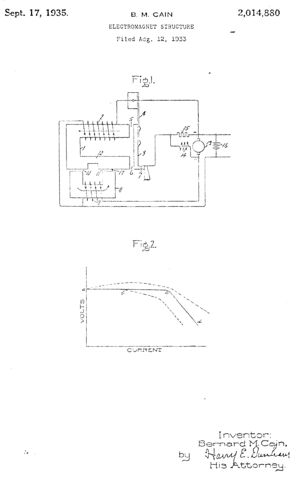

In 1933 I came upon the above scene as a student engineer assigned to work with Max Whiting in Industrial Engineering. We were having problems with holding constant voltage and with temperature compensation. My US patent 2014880, an improvement on the Teare-Whiting patent helped. The temperature compensation problem was solved by using a material having a negative temperature coefficient of electrical resistance. However our big problem was cost. Contacts with the automobile manufacturers had already indicated that our costs were too high to interest them.

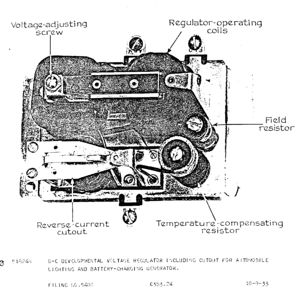

Charles Kettering has related many anecdotes about his experiences in introducing new ideas to those in control of final design. The position of manufacturing was make it better and lower cost, but don't change anything. We encountered the same thing. For example the reverse current relay had always been mounted directly on the generator. So we were told that no consideration would be given to a regulator that could not be mounted directly on the generator. To avoid the effects of engine vibration we wanted to mount our regulator on the wall of the engine compartment. We were told that this would involve added cost which could not be tolerated. We spent nearly a year of ddsign and testing to meet their specification. That year may well have been crucial to the success of our project.

After trials of a new regulator (I had one on my 1934 Ford) and with favorable cost Karl Pauly decided he was ready for an all out effort to convince the large automobile manufacturers. We had already had some success with Studebaker and a small parts vendor but we had ndt made any actual sales.

To try to interest the largest automobile manufacturers Bill Cronkite, supersalesman from Bill Miller's Industrial Sales group, made the calls and I accompanied him to make the ensineering sales pitCh.

Some managers were pretty well convinced that the idea of voltage regulation as opposed to constant current and backed by the General Electric name and reputation would have sufficient customer appeal to give an advantage to their product. He were pretty close to success.

Unfortunately there was one weekness in our offer and the automobile technical people saw this. While we had a patented device we did not hold a tent on the basic idea of voltage regulation. It was an old idea and could not be patented.

Our patents covered only the principals of combining all the required functions in a single device. This was a distinct cost advantage. However if they could design a three unit deVice having separate voltage regulation, separate current control separate reverse current relay at a cost comparable to the cost to purchase our device they had it made.

All we really were offering was the General Electric name and know-how. Fortunately for the driving public, we we got no takers for our regulating device.

A few years later, in the late 30's, the automobile manufacturers. announced voltage regulation. Their designs all avoided our patents using three separate devices for tile three control functions, voltage control, current control, and reverse current relay. Also they mounted their devices on the wall of the engine compartment just as we recommended.

With voltage control, instead of constant current battery troubles soon began to be a forgotten thing of the past. Winter starting was no longer the problem it had been. Five year battery life was not uncommon. But few, if any, are aware that it was at General Electric where the whole idea got started.

There is still more to this story. Even in those early days we recognized the possibility of greatly simplifying the automobile generating system by generating alternating current with a simple alternator and using a rectifier to provide direct current. Frank Merrill and I designed and built the first such alternator. But we did not have a rectifier of low enough cost and suitable characteristics to make the project a success. It was not until the advent of the silicon rectifier and the transistor in the 1950's about 20 years later that the modern automobile alternator replaced the commutator direct current generator and its vibrating contact voltage regulator.

With this modern solid state system our battery troubles are rare indeed. Even the battery people have made their contribution so that we no longer have to add water to our batteries. And so, at last, the goal of Karl Pauly and Max Whiting in the early 1930' s of a trouble free and essentially maintenance free electrical system for our automobiles has been achieved.