Electrical Excursions of Mathew Fontaine Maury (1806-1873)

Maury and the Sea

Mathew Fontaine Maury was on 14 January 1806. Probably few readers of this article will recognize the name. But to those interested in the science and history of the sea, Maury is a pioneer in oceanography and meteorology. First, as a young officer in charge of the U.S. Navy's Depot of Charts and Instruments, and later as director of the U.S. Naval Observatory, Maury embarked on a detailed and systematic analysis of the spatial and temporal behavior of the Earth's atmosphere and oceans. Although these peacetime scientific pursuits dominated Maury's professional life, the demands of war led him to develop the first application of electrical technology to naval warfare.

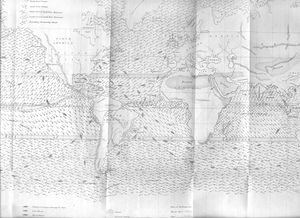

Maury understood full well the great benefits to the United States of mapping the world's winds and ocean currents. By 1850, U.S. territorial ambitions had reached out to the west coast. Until the completion of a transcontinental railway in 1869, the sea offered the most practical and economic means of moving manufactured goods and natural resources between the east and west coasts. It was a journey that went around the infamous Cape Horn at the tip of South America, and spanned three oceans. The Panama Canal was still 60 years away. As rough as the sea could be, people who could afford it preferred the relative safety and comfort of the sea route over the land route. The sea offered the added advantage of being navigable in winter, whereas winter travel for horse and wagon was almost impossible. If the United States was to forge an East-West national territory, then it would have to master transoceanic routes that spanned half the planet. Steam power was making its way into maritime transport, but sail still dominated the movement of people and goods. With sail, the shortest distance between two points was not the fastest. Good navigation had to be supplemented with accurate information on the wind and current patterns at various places around the world. This knowledge also had to account for seasonal changes in such patterns. Until Maury, such knowledge was quite crude.

With the discovery of gold in California, people from around the world poured into the state. The economic incentives to reduce maritime travel time between the East Coast and California jumped dramatically. In 1849, sailing times from New York City to San Francisco averaged about 180 days (half a year!). By 1855, the use of Maury's maps had reduced the average sailing time from New York City to San Francisco to 133 days.

An even more dramatic testament to the utility of Maury's work was the famous race in 1851 between the two clipper ships, Flying Cloud and Challenge. The "extreme" clippers represented the most advanced technologies in commercial transport under sail. Highly publicized, the race captured the nation's imagination. It had all the elements of an epic contest: man against the sea; ship designer against ship designer; crew against crew; and skipper against skipper. Flying Cloud won by a wide margin and made the voyage in an astounding 89 days. Their design and skilled captains were clearly important reasons for the speeds the extreme clippers attained, but Flying Cloud had an advantage that Challenge did not have — Eleanor Creesy. Eleanor was the wife of Josiah Creesy, the Flying Cloud's captain, and an exceptional woman. Not only was she the ship's navigator and well versed in the mathematics of celestial navigation, she was also an early follower of Maury's pioneering work in oceanography and meteorology. Up until 1860, Maury's professional life had been dedicated to the U.S. Naval Observatory and to his studies on the sea geography. Then, war pushed Maury in an unexpected direction: the use of electrical technology in naval warfare.

Maury and the Confederacy

When the Civil War broke out, Maury resigned his commission in the U.S. Navy and his position as Director of the U.S. Naval Observatory. It was with great regret that Maury left the Observatory, which he had set up. "Its associations," Maury wrote to Lieutenant Whiting, who was the next in authority, "the treasures there, which with your help and that of thousands of friendly hands, had been collected from the sea, were precious to me, and as I turned my back upon the place ,a tear furrowed my cheek." Maury felt that he had no choice. He saw himself as a Virginian whose heart and mind was with the Confederacy. Maury immediately offered his services to the cause of the South and was granted a commission as commander in the Navy of the Confederacy. Shortly thereafter, he was appointed Chief of the "Naval Bureau of Coast, Harbor and River Defense." Maury's mind turned immediately to the development of electrically detonated naval mines. The telegraph had already illustrated the importance of electrical technology in military affairs. But the use of the telegraph in war was merely an extension of the commercially successful technology that Morse had pioneered long before Civil War broke out. On the other hand, Maury's idea appears to mark the first time that electrical technology is applied directly to a weapons system.

Electric "Torpedoes" Mines

To protect the Confederacy coasts from northern naval forces, Maury advocated a network of naval mines, or "torpedoes" as he called them, to guard the entrances to strategic harbors and rivers. Maury envisioned a dense cluster of mines capable of catching any enemy ship in its deadly net. The problem was that if the mines were detonated through direct contact with a ship, then any great dispersal of mines could just as easily destroy Confederate ships. But, if the detonation could be achieved through an electrical signal sent from land observation posts, then Confederate ships could move easily — and safely — through the mines, while Union ships could not.

Maury's efforts to develop his electric "torpedoes" immediately ran into problems. He could not find sufficient insulated wire. He sent a secret agent to New York to buy and smuggle out the needed wire. But the mission failed. Rather than stop all his work, he temporarily shifted his efforts to developing "contact" naval mines. Detonation was to come from some form of mechanical interaction between the enemy ship and the mine. Even this non-electrical alternative proved difficult to implement. The mines were to be submerged below water to escape detection. Prototypes successfully tested at 10 ft. of water depth failed at 20 ft. The greater pressure found at 20 ft. made it more difficult for the fuse to burn. He did succeed in deploying these mines, but they were very temperamental and their effectiveness uncertain. Then, serendipity brought Maury the opportunity he needed to return to his electrical option.

In 1862, the Union forces wanted to establish telegraph communications across the Chesapeake Bay. With the wire already run under the water, the North had to abandon its plans. In May of 1862, shortly after the famous battle between the Monitor and the Merrimack, a storm hit the Chesapeake and washed this wire onto the shore near Norfolk, Virginia. Now, Maury had ten miles of insulated wire for his experiments. In June 1862, Maury successfully mined the James River with his electric "torpedoes." Wires ran from the mines to large batteries on shore. Although this time was the first that an electric mine had been used against an enemy in war, Maury did not have original ownership of the idea. Robert Fulton had a similar idea but was never able to make a working prototype. In 1842, Samuel Colt blew up a raft with an electric mine as part of and Independence Day. Maury, however, was the first to show that such a weapon was practical for warfare. An 1865 report from the Secretary of Navy for the North underscores the effectiveness of Maury's naval mines. The report states that "the navy lost more vessels by torpedoes than from all other causes whatsoever."

Always an outspoken man, Maury soon entered into a public argument with the Secretary of the Navy for the Confederacy, Stephen Mallory, over the kind and size of navy the South should have. Maury had become a painful thorn in Mallory's life. To rid himself of this all-too-public problem, Mallory arranged for Maury to take up a foreign posting in England. There, he would promote the Confederacy's interests. In addition to procuring British-made ships for the South, Maury again threw himself into his work on electric "torpedoes." Working with Wheatstone, Maury pursued secret experiments for the British. In return, Maury was able to get large quantities of British-made insulated wire and material for batteries shipped to the Confederate forces.

Maury had established an international reputation, and on numerous occasions, the French, Russians and British tried to induce him to work for them. Napoleon III asked Maury to abandon the South and head up France's National Observatory. Grand Duke Constantine, the Grand Admiral of Russia, offered Maury and his family a grand estate and a life of comfort in Russia. But Maury felt honor bound to stay at his post until the end of the war. When the Civil War ended, Maury wrote a formal letter of surrender to the officer in command of the United States naval forces in the Gulf of Mexico. He was ready to hand himself in as a prisoner of war. But Maury's friends warned him that a great deal of hostility existed toward him. While many officers had switched allegiances at the outbreak of the Civil War, Maury was singled out for the harshest of criticism. Maury's friends felt the North would be particularly vindictive towards him. "Do not come home," wrote Maury's daughter, "General Lee told me the other day to tell you not to." Instead Maury went to Mexico on Maximilian's invitation. As soon as he arrived in Vera Cruz, in 1865, Maury immediately offered to demonstrate his electric torpedoes to the Mexican military.

Although a scientific and naval visionary, Maury lacked political acumen. Still committed to the ideals of the South, he came up with a bizarre scheme to recreate pre-Civil War Virginia in Mexico. He wanted Maximilian to encourage the large-scale immigration of Virginian land owners, and their slaves, of course, to Mexico. Intrigued with the idea, Maximilian appointed Maury Imperial Commissioner of Colonization. Again, General Lee advised Maury against this foolish enterprise. Maury also seriously misread the post-war sentiment in Virginia. Few wanted to emigrate. With the project going nowhere and the instability of Maximilian's regime finally apparent, Maury drifted back to England to join his family. Although general amnesty would not be officially declared until 1872, Virginia had passed from military rule to home rule. Friends advised Maury that it was time to return home. In 1868, Virginia Military Institute appointed Maury to the new Chair of Meteorology. He died on 1 February 1873, after a long illness. Maury had been long forgotten, until 1923, when the state of Virginia dedicated a memorial to him. On it are inscribed the words:

Pathfinder of the Seas

The Genius Who First Snatched

From Oceans & Atmosphere

The Secret of Their Laws

Though he was not a pathfinder in the new science and technology of electricity, Maury did have a pioneering attitude towards the use of electricity in naval technology.

References

Charles Lee Lewis, Matthew Fontaine Maury: The Pathfinder of the Seas, (Annapolis: United States Naval Institute, 1927).

Jacquelin Ambler Caskie, Life and Letters of Matthew Fontaine Maury, (Richmond, Virginia: Richmond Press, 1928).

Patricia Jahns, Matthew Fontaine Maury & Joseph Henry: Scientists of the Civil War, (New York: Hastings House, 1961).

Frances Leigh Williams, Matthew Fontaine Maury, Scientist of the Sea, (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1963).

Chester G. Hearn, Tracks in the Sea: Matthew Fontaine Maury and the Mapping of the Seas, (London: International Marine, McGraw-Hill, 2002)