Edison Effect

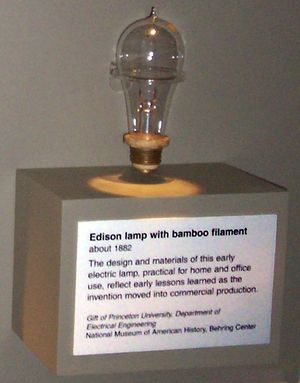

In early 1880, Thomas Edison and his team were hard at work trying to find a light bulb filament that worked well. He had already settled on a carbonized (burned) bamboo filament, but even this solution was not perfect. After glowing for a few hours, carbon from the filament would be deposited on the inside walls of the bulb, turning it black. This would not do.

Edison tried to understand what was happening. His assistant noticed that the carbon seemed to be coming from the end of the filament that was attached to the power supply, and seemed to be flying through the vacuum onto the walls of the bulb.

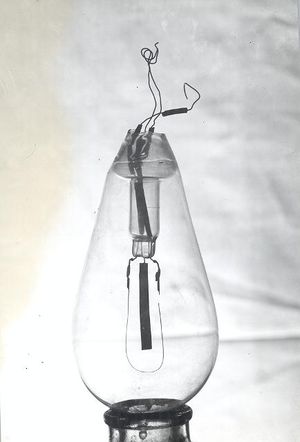

Edison determined that not only was carbon flying through the vacuum, but that it carried a charge. That is, electricity was flowing not only through the filament but also through the evacuated bulb. In order to measure this flow, he made a special bulb with a third electrode, to which he could attach an instrument to measure the current. He reasoned that if the current would flow between the two ends of the filament, it would also flow to this third electrode.

While he was proven to be right about the flow, Edison could not explain it, and the third electrode did not prevent blackening of the bulb, so he moved on to other experiments. But he did patent the new device, because he believed that it might have some commercial applications, such as measuring electric current.

Although he did not realize it, Edison had discovered the basis of the electron tube (also called a vacuum tube). Many years later, modified light bulbs would be used not to make light, but to control a flow of electrons through a vacuum. The electron tube would become the basis of modern electronics. Years later, when he was elderly, the discovery of what became known as the “Edison Effect” was remembered, but because Edison had no idea what it was or how it worked, he is rarely given credit for this contribution to the development of electronics.