Early Uses of Radio at Sea

The earliest use of radio aboard ships was as an extra service to wealthy passengers who wanted to monitor their stock investments and run their businesses while at sea. It was not until after the Republic and Titanic disasters that radio evolved from a luxury to a necessary safety device.

Early in the morning of 23 January 1909, 80 kilometers (50 miles) south of Nantucket Island, the Italian ocean liner Florida was off course in the dense fog of the Atlantic. Suddenly there was a crash—the Florida had collided with another liner, the White Star liner Republic. The Florida’s bow drove deep into the port (left) side of the Republic, near the ship’s engine room. The resulting gash was below the waterline. To keep the boilers from exploding, Republic’s crew shut them down. This saved the ship, but without generators, there was no electric power for lights or radio. The Florida, whose engines were still functioning, was not equipped with a radio, so despite the heavy damage, it was up to the Republic to send a distress call.

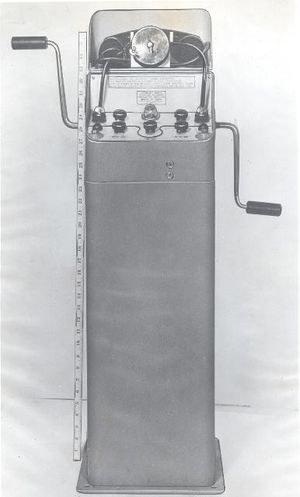

Jack Binns, the Republic’s 25-year old radio operator, rushed to his radio cabin, which had one of its walls ripped away in the collision. Fortunately, the antenna was still intact and emergency batteries supplied enough power to transmit a signal 95 kilometers (60 miles). The nearest land receiving station on the island of Nantucket was just about that distance away. Binns transmitted the Morse code distress signal of the day, CQD (“seek you;” the D stood for urgent). A Nantucket station retransmitted the message and several ships in the area steamed towards the ships in peril.

It was clear that injuries to the Republic were serious, and passengers and crew began evacuating to the damaged Florida, at best a stop gap measure. The lives of more than 1,650 people were in jeopardy. Binns stayed aboard the sinking Republic trying to direct nearby ships toward them. One, the Baltic, headed over. In the dark and fog, however, the Baltic had trouble finding the lightless Republic and proceeded slowly to avoid accidental collision. The crews of Baltic and Republic listened carefully for each other and then sent radio messages back and forth to determine their relative positions. Finally, at 7:20 p.m., after more than twelve hours of Jack Binns working his telegraph key in the freezing cold, the Baltic came into sight and rescued the remaining crew of the Republic. The French liner La Lorraine, meanwhile, had found the Florida. When dawn came the next morning, it was determined that apart from two passengers aboard the Republic and four crew members aboard the Florida who were killed in the collision itself, no lives were lost in the rescue. Radio had proven itself as a life-saving device at sea.

Binns testified before the United States Congress on the importance of radio at sea, but unfortunately, his advice went unheeded. For his bravery, the French government awarded him a medal. His employers rewarded him three years later by offering him the most prestigious radio operator assignment in their fleet—aboard their brand new ship Titanic. Luckily for him, Binns turned down the offer.