Did the Telegraph Broaden Women's Sphere?

By the late 1800s widespread usage of the telegraph had transformed the United States and the world. Along with the railroad, the telegraph helped spawn a mass, integrated, national market that brought the country and nations closer together than ever before. As the importance of telegraphy grew, demand for skilled telegraph operators grew with it. This growth created new opportunities for women to enter the workforce in greater numbers than ever before. This new opportunity, however, came with hidden costs.

The female telegrapher was a common sight in post-Civil War America. Telegraph companies welcomed the hiring of women because their hands were generally smaller and therefore better suited for the task of telegraphy. Just as important, they could also pay women less than men, as women’s work outside the home was considered supplemental to household income and therefore less valuable. Women benefited from jobs in telegraphy by gaining more independence and disposable income, which allowed them access to the booming consumer and entertainment revolution that swept the United States in late-19th and early-20th centuries. Telegraphy also opened ways for women to learn new skills, engage in new social networks (especially in the increasingly gender-mixed work place), and the chance to earn a degree of higher education.

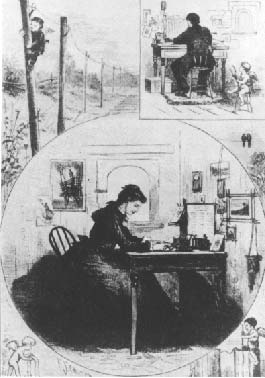

This plate from Harper's Weekly puts women at the center of telegraph operation. The cherubs in the corners and on the pole represent love. Men and women working as operators often “talked” during down time and romance ensued. Sort of like Internet dating for the 19th century.

An overemphasis on the positive aspects of the telegraph industry on women, however, can be deceiving. Most women telegraphers were young, in their late teens and early twenties. They were largely poor and unmarried. Only a few ever moved above the position of standard telegraph operator. Most women telegraphers worked for a couple of years then married and settled into their “proper” role as housewives and mothers. The companies that hired women operated on this assumption, which provided them with a young, stable, temporary workforce that could be paid low-wages precisely because the job was on a temporary basis. Providing extra income for her family, not disposable income for herself, was also the more common reality among women telegraphers. Observers at the time noted seeing women telegraphers sewing and knitting on their breaks from the telegraph board. This indicates that entering the workforce neither changed notions of women’s traditional responsibilities nor freed them from household work. Rather than fostering their independence, in many instances work in telegraphy enmeshed women telegraphers deeper in a family economy that depended on their wages.

Nonetheless, the paths to employment for women opened up by the development of telegraphy began a radical transformation in American society. It provided women with the opportunity to learn new skills and earn an income of their own. If the way the world saw women didn’t change, the way women began seeing themselves did. Working outside the home proved to be an impetus to the burgeoning women’s rights movement of the early 20th century.