Oral-History:Vincent Perry

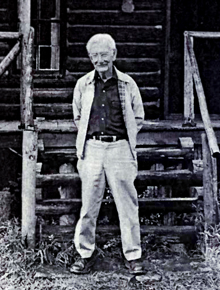

About Vincent Perry

Vincent Denis Perry is vice president-geology of The Anaconda Company. He has been with the company for more than 45 years during which time he has been responsible for the development of many important mines and geological techniques. Under his leadership, Anaconda has projected its capability to produce copper at the rate of one million tons per year in the early 1970's, a 50% increase over five years. Anaconda's growth has also included further development in such basic metals as uranium, molybdenum, beryllium and others.

Mr. Perry joined Anaconda in 1924 as a mining geologist in Butte, Montana. In 1928 he was sent to Cananea, Mexico, as chief geologist for the Anaconda subsidiary, Compania Minera de Cananea, where he remained until 1937. He then returned to Anaconda as exploration geologist, first in Los Angeles and later in Salt Lake City. From 1944-1945, he served as chief geologist for another Anaconda subsidiary, International Smelting and Refining Company.

Mr. Perry was named assistant chief geologist for Anaconda in 1945, chief geologist in 1948, vice president and chief geologist in 1957, and vice president-geology in 1967. He is president of Anaconda Australia, Inc., and vice president of the Anaconda Company Limited (Canada) and Anaconda American Brass Limited, all Anaconda subsidiaries. He has been a director of Anaconda since 1966and also holds directorships in several subsidiary companies of Anaconda throughout the Western hemisphere and Australia.

In 1961, Mr. Perry received AIME's Jackling Award and was also the Jackling Lecturer. The subject of his paper, "The Significance of Mineralized Breccia Pipes," was drawn from his own observations of the geology of La Colorado orebody, Cananea, district.

He holds a B.S. in mining engineering from the University of California at Berkeley, an M.S. in mining geology from Columbia University and a doctor of science in geological engineering from Montana Tech.

Further Reading

Access additional oral histories from members and award recipients of the AIME Member Societies here: AIME Oral Histories

About the Interview

Vincent Perry: An Interview conducted by Eleanor Swent in 1990, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1991.

Copyright Statement

All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Vincent D. Perry dated March 13, 1990. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley.

Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the Regional Oral History Office, 486 Library, University of California, Berkeley 94720, and should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user. The legal agreement with Vincent D. Perry requires that he be notified of the request and allowed thirty days in which to respond.

It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows:

Vincent D. Perry, "A Half Century as Mining and Exploration Geologist with the Anaconda Company," an oral history conducted in 1990 by Eleanor Swent, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1991.

Interview

INTERVIEWEE: Robert S. Shoemaker

INTERVIEWER: Eleanor Swent

DATE: 1999

PLACE: Berkeley, California

Swent:

Mr. Perry, do you want to tell a little bit about your family and your early years in San Francisco?

Perry:

I was fortunate to arrive at the start of the twentieth century, and to have had the opportunity to live through this great, action-packed period in our history for most of that century. I was born in San Francisco, California, November 26, 1901, of devoted parents, whose ancestors went back to the Gold Rush days. My father's brother was married to my mother's sister so there was a close relationship that made my aunt and uncle really second parents to our family. They had no children so we provided a family for them.

They lived next door to us on Sacramento Street, just below Leavenworth. We were a closely-knit family group, and I was the oldest child. My sister Eleanor followed me, and then a brother, Frank, and finally my younger sister, Mary, who arrived just six weeks before that terrible date, April 18, 1906, when San Francisco suffered the devastation of the earthquake and succeeding fire.

Swent:

Do you recall the earthquake at all?

Perry:

It is my earliest childhood memory. I was in my own bedroom and was awakened by the smashing of a large picture of the Madonna against the wall, and of my mother rushing in to douse a little kerosene lamp that I had by my bedside. My dad early that morning put me on his shoulders and carried me to our roof garden where we could look out over a large part of San Francisco, particularly the section extending southwesterly along Market Street to Twin Peaks. And there the sight of the entire city in flames was an awesome one, indeed. I suppose my dad and my uncle, too, began early efforts to try and get us out of our homes and to some place of safety. They found a lot of cooperation in the help of soldiers, members of the United States Army, who had been assigned to the disaster areas from their headquarters in the Presidio to restore order and protect against looting. They also provided water, food and shelter for people that had suffered complete loss of home and essential services.

My dad had a business in downtown San Francisco, and he left almost immediately for his office, where he arrived just ahead of the advancing flames, entered his vault, and recovered all his essential papers, including the insurance policies that covered our properties. He started back up the Sacramento Street hill past the Fairmont Hotel, and the weight of the books was almost too much for him. At that time he was accosted by a lone Chinaman who said, "Me help you." This good man assisted my dad up to Jones Street at the top of Nob Hill, and there my dad took over the burden again. He reached into his pocket and handed the Chinaman a one-ounce $20 gold piece. The Chinaman said, "Me no take your money. Me likee Americans. " Which my father thought was a wonderful thing to happen, and it shows what people do, particularly under times of stress, and in this case, an Oriental who was simply being a good Samaritan in his adopted land.

We waited out the first two days of the fire, watching it creep towards us from different directions. It was a terrifying time, and I know my folks were attempting to get together some sort of organization so that an escape would be possible. My dad had many friends in San Francisco, and on the morning of the third day he showed up with a horse and wagon. I don't know where he found them or who let him have them, but at any rate, he loaded that wagon with the things that my mother wanted to save, clothes and some supplies.

We started out that morning with me perched on the wagon beside my dad; my uncle, aunt, and mother on foot beside us pushing the baby buggy with my brother Frank and my tiny baby sister, Mary, in the buggy; and Eleanor, who was about three years old then, trotting alongside them. We went northerly towards, I believe, Pacific Avenue. I suppose the direction was generally obtained from army personnel who were doing everything to try and help the movement of refugees away from the fire area. Most people went out to the Presidio, where tents had been set up, and soup kitchens provided for feeding thousands of people. My dad decided he wanted to head eastward across the Bay to Alameda County. We went east on Pacific Avenue, and apparently the army had cleared the street of enough rubble and debris so we could get through. We skirted beyond the fire front which was advancing northerly in that area. My one vivid memory is looking down those cross streets through literally tunnels formed by the towering flames that reached several hundred feet in the air and crested in huge explosive flares.

We reached the Embarcadero and moved south to the Ferry Building. I doubt that we were able to get the horse and wagon on the ferryboat, and we probably lost some of our luggage, although I have no clear memory of that. At least we did get across to Oakland and down to Centerville in Alameda County, where my dad's parents had a farm. We finally arrived there late that night, and with great relief and thanksgiving we had our first normal night's sleep.

Swent:

Where is Centerville?

Perry:

Centerville is now part of the city of Fremont. At that time it was wide-open farm country with a farmhouse every half-mile or so. It was beautiful country, and I remember it so well because it was my first experience away from the streets and sidewalks of San Francisco. I remember going out that next morning and seeing this tremendous fig tree, something that I had no real concept of until that moment. It was a tree that had a spread of over a hundred feet, its branches held up by wood supports, and it must have been planted in the very early days when my grandparents located or bought the farm. The land was close to Alameda Creek and well watered. It was excellent farming country.

After the first few nights of sleep and rest and recovery, my folks found a place in San Leandro where they rented a house, and we settled there temporarily until we could get back to the reconstruction job in San Francisco. My parents went back and forth to the city, and within a very short period--! would judge it wasn't more than a month or two- -they were able to collect the insurance from Fireman's Fund Insurance Company so that they could start rebuilding. The first two structures that were put up were portable houses on Kimball Place, which is a small, side street off Sacramento close to Leavenworth. My parents and my aunt and uncle moved there in 1907 while plans were made to rebuild their houses. The construction was started on them immediately so that we moved into our new homes in a very short time, probably the spring of 1908, although I am not sure of the exact date.

Swent:

You might tell about the insurance.

Perry:

Payment of insurance was a remarkable operation, done under difficult conditions, and with very little in the nature of office facilities. The Fireman's Fund Insurance Company, which carried the insurance on our homes, had the financial resources and also the will and the spirit to meet punctually its full financial obligations. The company set up an outdoor office on Market Street, and people stood in line out in the street, waiting their turn and with their papers in hand. As they approached the desk, papers were expeditiously checked. If the papers were in order, the insurance was paid out with minimum red tape. I remember that line and holding my mother's hand, as we waited patiently for our turn. My parents apparently had no difficulty in recovering the insurance on our properties in San Francisco and this, of course, greatly facilitated the early rebuilding of our homes, my parents' and my aunt's and uncle's.

Swent:

Times have changed.

Perry:

Yes, this was done in a period when there was no government agency to facilitate such rehabilitation. But the United States government certainly did help through the judicious use of its army services. I think the army deserves a great deal of credit for the emergency control it established and the early recovery that was made in San Francisco. The Presidio was a main military establishment, and it lived up to all its obligations and duties. I think that was a very impressive contribution.

Swent:

So you started school, then, back in San Francisco.

Perry:

I started school almost immediately after we moved into our new home. It was the Redding Public School in San Francisco. Within a year, my dad decided that it was not the healthiest thing in the world to raise four children in the city. So, in that summer of 1909, shortly after I'd started school, we moved to Mill Valley in Marin County and rented our place in San Francisco to the Kress family, who were good friends of ours. The Kress’ owned and operated a high-quality furniture store at the corner of, I believe, Stockton and Sutter--at least in the general Union Square shopping area. They were wonderful tenants and my parents were fortunate to have them. We went ahead and bought a place in Mill Valley and I proceeded with my schooling there, and my sisters and brother followed me. We all attended Tamalpais High School, and when I finished high school the question was, "What do we do about the university?" My dad decided that he wanted to keep the family together, so we sold our home in Mill Valley and bought a place in Berkeley on Virginia Street just south of Euclid.

Perry:

My first six months at Berkeley, while the sale of the property was proceeding, was spent alone on the campus, and I, of course, wanted to join a fraternity. My dad didn't think too much of that idea. He was in the wool business- -and had some close contacts with the Koshlands and others in the Jewish community in San Francisco. He said, "There's a Mrs. Breslau, a widow who lives near the North Gate of the Berkeley campus. I've arranged to have you room and board with her." [laughter] It was not particularly pleasing to me, but in retrospect, I look back and think that it did me a world of good, because it just happened that there were three or four Jewish boys that were freshmen with me and stayed at the Breslau home. They were marvelous students, and they taught me how to use the library and how to study. I am eternally grateful for that experience; otherwise I might not have gotten off to a really good scholastic start at Berkeley.

Swent:

What were their names?

Perry:

Heller and Hellman are names I remember. There were others, and they became very prominent in San Francisco business affairs. I can't recall their names now, but I remember Heller very well because he was most helpful to me. He was a history major, and told me about Henry Morse Stephens and the wonderful history courses he was giving. So despite the fact that I had decided by then that I wanted to be a mining engineer, Heller talked me into taking two courses with Henry Morse Stephens: one, "War Issues," and the other, "Peace Issues," which were so appropriate to that time when World War I had just ended. Stephens was a noted historian and a great speaker, and I learned a lot in those two courses. They were helpful to me in my life afterwards, even though they had no direct relation to engineering.

Swent:

So if you were taking an engineering degree, you were not required to take any liberal arts courses?

Perry:

Practically none; the engineering courses at the University of California at that time were fully packed with required engineering subjects, including math, physics, and chemistry with limited electives. I made a point of trying to take electives because I felt that I needed at least a minimum of broadening in addition Co all of the science courses that were heaped upon me. I tried to do that through my four years, but it was a difficult thing to do because of the very strict scholastic requirements of the College of Mining. They had a particularly difficult curriculum because it included mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, civil engineering, and geology, in addition to the required mining and metallurgical courses.

Frank Probert was dean of the College of Mining, and I developed a very great respect and admiration for him. He gave several mining courses, and was assisted by a fine staff, including Professors Weeks, Uren and Morley. There were others on the staff whose names I don't recall at the moment.

My interest in geology was primary because I 'liked the subject and wanted to follow in the exploration branch of mining. But I realized that to be competent in the search for new mines you had to understand the elements that are essential in constructing a successful mining operation. I enjoyed the engineering courses and they supplemented the ones I took in the Geology Department under Professors Lawson, Louderback, Taliaferro, and Eakle, the mineralogist. They were all excellent teachers. Louderback was particularly effective with his students in the field. He'd take us out every weekend, sometimes just through the Berkeley Hills, but also on long trips into the Sierras and to various mining districts where we had a "chance to see and map mine -related geology. He insisted on our making careful and accurate maps, taught us how to pace long distances, locate ourselves by triangulation and Brunton compass, and measure with accuracy the things that we observed. He was a great observer himself, and stressed the importance of observation in any kind of geological investigation.

Swent:

Did you do a lot of mapping?

Perry:

We did a lot of mapping, and that was a wonderful opportunity to learn how to do these things in the field, not just to study textbooks and learn the theory of geology. The training at Berkeley emphasized field experience and the obtaining of factual data. It was the kind of training that I found in later years to be most beneficial in doing geological and exploration work.

Swent:

And this was not true at all universities at that time, was it?

Perry:

Well, I'm not sure. Later, when I took my graduate work at Columbia, I found that there was more emphasis at Columbia on the theoretical side of geology, although we did go on several field trips in New Jersey and upstate New York. I think that the bigger, first-class schools that specialized in geological training or mining geology generally followed the primary axiom of learning how to do field work and how to put the observed facts on paper so that you had a basis for reasonable analysis of what you were looking at and what this meant.

Swent:

Let's go back just a bit. How did you happen to get interested in studying mining at all?

Perry:

My dad wanted me to go into the wool business with him. He had a plant in San Francisco that bought, washed and graded raw wool. It was called the Western Wool and Warehouse Company. I worked there two summers, and after seeing the general nature of the work, it had little appeal for me.

Swent:

How old were you when you first worked there? Do you remember?

Perry:

It was, I believe, at the start of my sophomore year in high school. About that same time, we had a neighbor in Mill Valley by the name of Herbert Lang. Lang had a son who was about my age, and we were good friends. The father was a mining engineering graduate from the University of California who had worked in Montana and been successful enough to acquire an attractive home in Mill Valley, who had retired at a fairly young age, and had become a consulting mining engineer. He took great delight in showing his son how to sink shafts, build model headframes, et cetera. I became part of that boyhood coalition, and our greatest achievement was the sinking of a four teen- foot deep shaft, timbered and equipped with hoisting windlass, in the backyard of the Lang home. My first summer after entering Berkeley, he gave his son and me jobs in a mine he was opening up at Round Mountain, Nevada. After the summer job experience in Nevada, I decided that despite my father's desires, I was not going to go into the wool business; I was going to concentrate my studies on becoming a mining engineer.

Swent:

What did you do in the summer up in Round Mountain? Were you actually working?

Perry:

Yes, we worked. My brother joined Herb Lang and me, and at first we worked on the graveyard shift tending the flumes. It was an hydraulic operation using giant monitors to wash down the gold-bearing gravel. Water was brought from the Toiyabe Mountains across the valley and into Round Mountain, and the gravel was washed from the alluvial deposits that flanked the west side of the mineralized core of the Round Mountain district. It was a great experience; I learned a lot. The mine foremen were good at moving us into a variety of jobs such as how to drill holes in the large boulders that were left after the hydraulic washing process, and how to load those holes and ignite the charges, and then run for cover. It was a lot of fun for us youngsters. We learned quite a bit about some of the fundamentals of mining at that time.

Swent:

They would never let you do that today, would they?

Perry:

[laughter] Probably not, no. We were child labor, I guess. But it was a great experience, and we were fortunate to escape without any injury or problems. We learned to take care of ourselves.

Swent:

Where did you live?

Perry:

We lived at a little hotel in Round Mountain that had a dining room. We had a comfortable life.

Swent:

You were completely on your own? No parents there?

Perry:

Oh, no. No, we were completely on our own.

Swent:

That's interesting. So when you started the university, you already had some experience in mining.

Perry:

Well, I'd had the exposure to Mr. Lang's mining influence and, by contrast, had two summers working at my father's wool warehouse in San Francisco. Then my summer's mining experience at Round Mountain, Nevada, convinced me more than ever that I wanted to go into the mining profession. I found that at that time, the College of Mining at Berkeley had students that were oriented in a similar way. They were students that came either from mining families or at least from mining communities.

Swent:

It was a very popular department at that time.

Perry:

Yes, it was a popular department. It was a small department; there weren't many students, but I would judge there were perhaps fifteen or twenty in my graduating class. Two of my close friends, Larry Morel and Abe Yates, had just finished their thesis on the Homestake Mine. When Engineering Day came along in our senior year, we served together on a committee to organize the program. We set up a stamp mill in the Hearst Memorial Mining Building, with a crusher and a Hardinge mill. We had amalgamating plates, Wilfley tables, and a full-going milling operation for the visitors.

All of the mining students participated in this sort of thing. They liked to operate, they like to be part of a going concern, even though it was a miniature scale and on a university campus. But the spirit of mining was everywhere there in the college.

Incidentally, we had two members of the California Wonder Team of 1921 and '22 in that group--Dan McMillan and Jimmy Dean--who were out at football practice part of the time and yet were required to carry the same scholastic load that all the rest of us did, and they did very well. I was a great admirer of both those men. They were star football players, and yet they were able to maintain high scholastic grades as mining engineering students.

We were very proud of that Cal Wonder Team because those were the days when Cal was undefeated. In fact, I never attended a football game during my four years at Berkeley that Cal didn't win. [laughs] One of the most exciting trips I had was when a group of us got together the last day of 1920, and drove down the coast in a rickety old Franklin auto to Pasadena to see Cal beat Ohio State 28 to at the Rose Bowl. [laughs] So, those were some of the joys of being at Berkeley then, besides all of the gratification we got out of our scholastic work.

Swent:

Could you go to Los Angeles in one day?

Perry:

No, it took us two days. Two long, hard days. We left early in the morning from Berkeley and arrived at San Luis Obispo about eleven o'clock that night. I remember going over the San Juan grade coming into Salinas, and wondering whether we were ever going to make it. [laughs] Leaving San Luis Obispo at dawn, we arrived in Los Angeles just in time for the game.

Swent:

You didn't mention Professor Joel Hildebrand.

Perry:

Hildebrand was one of our fine teachers in the Chemistry Department. He was extremely popular. We'd be in the lab carrying on experiments in chemistry, and, even though we were being supervised closely by instructors, Hildebrand would always be there looking down our necks to see that everything went right, and never being too serious, usually coming up with some light remark or a pat on the back if things didn't go exactly as planned. But he was always an inspiration, and his famous display at Big Game time when he was able to show all kinds of college colors by performing chemical experiments on his lecture bench, was a delightful diversity to all his students. [laughter]

Swent:

You also liked Lawson, you said.

Perry:

I liked Andy Lawson because he was also a professor that stressed the humorous side of life and science. His famous remark, which I suppose was oft-repeated, about the terrible grumbling down in the bowels of the earth accompanying volcanic eruptions, always fascinated the class. He had many wise comments and he was a very able lecturer.

Swent:

You felt that you got good, practical academic training?

Perry:

I felt that the courses given at Berkeley were outstanding. I came away fulfilled in the sense that the people who had instructed us sounded as though they knew what they were talking about. They were men that had had a good deal of experience, and they spoke with conviction. I think they made a great impression on the students. I was very glad that I had had the opportunity to go to Cal and to enjoy that kind of contact. It was something that has been with me through all my professional life, and I am sure that the training I received was as good or better than anything that was available anywhere else. I say that advisedly, because after I had worked a year on the Mother Lode at the Carson Hill Gold Mines, I went to Columbia to do graduate work in geology.

Swent:

How did you happen to choose Columbia?

Perry:

I chose Columbia because I had an opportunity to meet Professor Robert Raymond, then Dean of Mining at Columbia, who was carrying on an investigation of the Carson Hill Gold Mines for a client. My job was to take him underground and generally be his helper and guide during the examination. He told me that he felt that it would be worthwhile for me to broaden my education by doing some graduate work at Columbia. His suggestions were so appealing to me that I decided that this was something that would be well worth doing. I had saved enough money from my work at Carson Hill so that I could afford the trip back East and the then very modest financial requirements of a year at Columbia University, besides living in the City of New York. [laughs]

Swent:

How did you get the job at Carson Hill? Let me go back. Did you work summers, there, also?

Perry:

Well, I worked one summer at Carson Hill. Then as graduation approached I thought that it would be important for me to find a job in a different place. I didn't want to just stay in the State of California; I wanted to get out and see the rest of the world. So, first of all, I had an offer from the testing laboratories of Anaconda, at Anaconda, Montana. They were looking for testing engineers, and I had tentatively decided on going up there when I received word that because of the end of World War I and the drop in the price of copper, their testing and research activities were being curtailed. So that job was closed.

Swent:

When did you graduate?

Perry:

I was graduated in 1922. Dean Probert told me he had heard of a job opening in mining geology at Cerro de Pasco in Peru. Don McLaughlin was then chief geologist of Cerro de Pasco and was in Berkeley on a vacation. Probert arranged an interview with McLaughlin, who gave me some encouragement and said that he would discuss my application with Dr. L. C. Graton at Harvard University, who was in overall control of the geological work of Cerro de Pasco at that time. Two weeks later a letter came back saying that Hugh McKinstry had been accepted as a geologist at Cerro de Pasco for the job I had expected to get. So that was closed.

My final opportunity was to go back to Carson Hill where I had worked the summer before, and I found that they were anxious to get me back on their payroll. I had worked before as a miner, and they made me an engineer. I also worked as a surveyor and in the safety department for the next year.

However, we experienced a calamitous event. The Argonaut Mine at Jackson had a disastrous fire. I was a member of the safety crew at Carson Hill and we were ordered out in the middle of the night to drive over to Jackson, about thirty-five miles northwest, to help in attempts to rescue miners trapped in the Argonaut. Forty-seven men were cut off from escape on the 4200 level. The main incline shaft was down-cast and the auxiliary vertical Muldoon shaft was up-cast, with fans sucking the air down the incline and through the mine workings where the men were trapped. The fire was burning in the main incline shaft, heavily supported with wooden timbers which provided readily ignitable fuel.

When the fire was thought to be controllable it was being fought by going down the main incline shaft with fresh air at the back of the fire fighters. At some critical stage the fire got out of control but the management persisted in fighting it through the incline and shut down but did not reverse the Muldoon shaft fan so the miners on the 4200 level were trapped by an ever- increasing flow of toxic gas and smoke.

The Bureau of Mines rescue group arrived the next morning from Berkeley, and the bureau chief decided that the only way to effect the rescue was to drive an incline raise from the adjoining Fremont Mine to connect with the Argonaut. It took three long weeks to drive the connection and when we finally got through the raise and into the Argonaut Mine, we found forty-six bodies piled up at the end of a crosscut. It was a terrible job to recover all those bodies and to haul them out of the mine through that narrow little raise up to the surface. The forty- seventh body was found later in another part of the mine. It was a tragedy that left a real imprint on me. I wondered whether mining was going to be as much fun as I had expected it was going to be.

Swent:

Did you think that the decision not to reverse the fan was correct?

Perry:

Timing was vital. The fan should not have been reversed as long as the fire was controllable. The Bureau of Mines agreed that the management was correct in not reversing the fan. But to me it looked as though they should have decided at some stage that the fire was uncontrollable and let the shaft burn out so that the men would have a chance to get out instead of facing all the gas and smoke that was being circulated through the Muldoon fan. That's something that I've wondered about, whether the decision was the right one or not. It's like many things that happen where a decision has to be made in a short period of time, and the decision, in my judgment, may have been wrong.

Swent:

But you were actually with the crew then that was doing the emergency raise?

Perry:

I wasn't a member of the crew that drove the raise; I was one of the group that entered the Argonaut Mine through the raise connection with the Fremont Mine and recovered the miners' bodies.

Perry:

I have a photograph taken at the face of the crosscut by the Bureau of Mines that reads, "Gas getting strong. 3 A.M. Fessell." It was written with the smoke of a carbide lamp. Fessell apparently was the leader of the men.

Swent:

Those are memories you don't ever lose.

Perry:

No. [pause]

Swent:

What did you do at Carson Hill?

Perry:

I was assistant engineer with the principal job of doing the surveying. My only real engineering achievement there was to survey and run a second exit raise and this happened immediately after the Argonaut incident. Probably our management was spurred to do this. We had an internal shaft from the 3000 level to the 4200 level. There was no second exit, so we started a 400- foot raise from somewhere between the 3000 and the 4000 to make a connection through to the 3000 level. It was an inclined raise and I had to make my survey down the main 60 -degree incline operating winze. The management was so hard-pressed to get out the rock that the hoisting skips were kept going on a 3-shift basis while I had my transit in the manway trying to take sights down that shaft. I remember rocks, small pieces flying off the skips, as they whizzed past me, and I wondered whether I was going to save either my transit or my head. [laughter] We finally got the survey down to the point where the raise was designed to start and it was driven on lines checked every few rounds to keep the heading on course. I was very happy when the day came that we broke through and the connection was within a couple of inches of being on the mark.

Swent:

Do you recall how much you were paid at Carson Hill?

Perry:

I was paid $150 a month. I thought that was pretty good pay in those days.

Swent:

So then you left all that to go to Columbia?

Perry:

Yes, and it was a five-day train ride in those days. I arrived at Grand Central Station in New York City, and as I exited from the station, there was a newsboy shouting, "Berkeley destroyed! Berkeley destroyed!" which was the first I heard of it. I had left California just before the disastrous fire of North Berkeley in September, 1923. Again, as in San Francisco, the homes of both my parents and my aunt and uncle were destroyed. That last event was too much for my mother; she was stricken with a heart attack and died within two months after the fire.

Swent:

Where was your home in Berkeley?

Perry:

North of the university campus on Virginia Street just below Euclid.

Swent:

And that was the part that was destroyed. Oh, that's terrible.

But you stayed on in New York; you didn't come back to California.

Perry:

No, I stayed at Columbia until my mother's death, and then I came back, but just for a short trip and then went right on back and continued with my courses at Columbia.

One of the things that Professor Raymond had advised me was to continue my mining engineering work, and he suggested it would be of professional benefit to get an M.E. degree from Columbia, which was at that time a six-year course as opposed to the four-year course at the College of Mining in Berkeley. I was in favor of that, and submitted my California grades for review. Raymond arranged interviews with different faculty members. Peele was then one of the leading mining professors at Columbia and the author of the famous Mining Engineers' Handbook. Meeting with Peele he asked me, "What did you get in the course Strength of Materials at Berkeley?" I was proud to tell him that I had received an A, because that was one of the toughest courses that was given on the Berkeley campus. He said, "I think you'll have to repeat the course here. We can't accept the credential from the University of California."

I was so distraught at that; I felt it was a snobbish attitude he was taking. I knew that the Columbia course couldn't be tougher than the one at Berkeley. It so influenced my thinking, that I decided rather than going ahead with my plan to get a mining engineer's degree I would get a Master of Arts in geology at Columbia. I changed my whole curriculum, with emphasis on courses in geology. I took one course in mining under Raymond, and another course--! believe in mine accounting--that I found to be interesting. But most of my work at Columbia was directed towards geology.

I decided that the training and the education that I had received at Berkeley as a mining engineer, was as good as I could get anywhere, and that there was little use of trying to "gild the lily" by getting a mining engineering degree from Columbia. I was better off specializing in some subject, and I was interested in geology. Increasingly I thought that maybe I would go into the oil business, because that looked so attractive from a monetary standpoint at that particular time in the early twenties, with all the important discoveries being made in the Southwest and in Southern California.

I had that pretty much in mind when I agreed verbally to accept a job with the International Petroleum Company in Mexico. It just happened that Reno Sales, chief geologist of Anaconda, was visiting the Columbia campus and had given a talk to a little club we had there called the Journal Club in which he told us about the work that was going on in Butte, Montana. I was impressed with his talk and with the man personally, and introduced myself after the program. He asked me what I was planning to do upon graduation, and I told him I was planning to go with an oil company. He looked at me rather disdainfully and said, "The trouble with you is, you want to get rich quick."

Sales's point that money wasn't everything sunk in, so much so that the next morning I looked him up at his hotel in downtown New York and asked him, "What about a job in Butte, Montana?" [laughs] He accepted me and said that there'd be a place for me as soon as I finished my work at Columbia. So I arrived in Butte in June, 1924, and started work with the Anaconda Company, and my whole professional life has been with that company.

Swent:

How much was your starting pay there?

Perry:

A hundred and thirty-five dollars a month.

Swent:

Before we go into the Butte experience, I did want to question you a little bit more about your feelings about the difference between Columbia and Cal.

Perry:

I found that Professor Raymond was a very helpful, friendly individual. I was impressed with him when I had that short visit with him at Carson Hill when he was making the examination and I was his helper. I found that when I arrived in New York, he was very generous and helpful to me. I, of course, was shocked by the news that our home had been destroyed in the Berkeley fire and about my mother's illness and he immediately pulled all the strings he could and established communications with Berkeley, contacting my family. I found the man was an extremely decent and kind individual.

I also found that generally at Columbia, this was the nature of many of the faculty, despite the brush-off I had received from Peele. There was actually at Columbia, I thought, a more intimate and personal relationship between students and faculty members than I had found at Berkeley. This may be a distorted viewpoint, because after all, I was a graduate student at Columbia, and maybe graduate students did receive more attention and more notice from the faculty than they would have received as undergraduates. But it was my experience that Columbia gave a great deal to its graduate students. I have a feeling of deep appreciation for what Columbia did for me. It is a second alma mater, and it in no way detracted from the fact that my first loyalty was to Berkeley.

Swent:

Did they give you help in getting a job, then, also?

Perry:

They were helpful, yes, in the sense that they had lined me up with the job with an oil company, and when I didn't accept that, it was through a meeting with Sales who was speaking under the auspices of Columbia University when he gave the talk that impressed me so much and made me want to in his department as a geologist.

Swent:

And he was from Columbia?

Perry:

He was a Columbia graduate, although he had done his undergraduate work at Montana State. He went to Columbia and took two additional years and received his mining engineering degree from Columbia.

Swent:

Is there anything else you wanted to say about the Columbia experience? Did the fact that you were in New York City enter into your education?

Perry:

Well, of course it did! New York was a great place for a young man to visit at that period, and I made some good friends. I enjoyed the life in New York City. It was a lot of fun, and of course, as fortune would have it, when I finally established my home in the New York area thirty-three years later, I felt that I knew the place, because I'd been there as a student in years gone by.

Swent:

And of course, at that time, most of the big companies had their head offices in New York, didn't they?

Perry:

That's true. The AIME [American Institute of Mining and Metallurgical Engineers] had its headquarters there. It was a very active organization.

Swent:

And the Mining Club was there?

Perry:

Yes, the Mining Club was there. There were a lot of advantages to being in New York. I had joined the AIME when I was a student at Columbia. They were very active on the Columbia campus. We had a student group and I attended all of the technical sessions and the social gatherings which gave me an opportunity to broaden my contacts with the mining fraternity.

Swent:

What was going on in the geology world at that time? When did the Wegener theory come in? Was it about that time?

Perry:

Well, the Wegener theory had been proposed before that, I believe about 1912. The idea of continental drift was a controversial subject, and I was impressed with it simply because of the beautiful physical fit between the east shoreline of South America and the west shoreline of Africa. It struck me as though it made a good deal of sense, but it was not accepted generally by the geological profession until much later, and the general ideas of plate tectonics took over and then it began to make more sense. But I think Wegener was really the father of plate tectonics.

Swent:

And this was coming in when you were in school?

Perry:

As I recall, it was something that was discussed as a very far-out, hypothetical, questionable sort of geological idea. The main discussions about the geology of ore deposits at the period were between the school that had been generally led by Josiah Spurr of United States Geological Survey, and a group including Allen Batemen, Waldemar Lindgren, and others who thought that Spurr and his ideas about the relationship between ore deposits and pegmatites was a far-fetched and erroneous sort of an approach to the nature of ore genesis. Their ideas, largely led by Lindgren, favored the theory of replacement over long, protracted time intervals, which ideas could be more readily corroborated by microscopic study of the ore minerals.

Generally, I think that their ideas were correct, although I think that Spurr, like many extremists, had simply gone too far. I think that his ideas about pegmatites, if treated with some degree of moderation, do fit into the overall picture of ore genesis. That thought was substantiated when I began my work at Cananea in the study of the great La Colorada ore body, which was at that time one of the greatest high-grade concentrations of copper in the world. I felt that there were very intimate relations between the magma and mineralization, and that those relations could be demonstrated and could be used in exploration work. So that Spurr 's thoughts, while they were discounted and ignored by the profession generally, I think did have some substance. It was interesting that this sort of thing was going on while I was taking my graduate studies at Columbia.

Swent:

And you were made aware of it.

Perry:

And I was made aware of it, so I knew a little bit about the pros and cons of the argument when I began my own field work and decided that maybe Spurr wasn't 100 percent wrong after all. I think there are many things like that in a science like geology, which is not an exact science- -it' s more of an art, in many ways--and requires a good deal of balanced judgment as to what you want to accept and what you want to treat with a good deal of suspicion, or at least caution. [laughs]

Swent:

Are we ready to move on to Butte?

Perry:

Sure. One of the advantages of working as a Butte geologist was the opportunity it offered to learn the fundamentals of applied mine geology. Butte practiced a special style of mapping and using geology in mine operations. The system had been developed by Reno Sales and probably to some extent by his predecessor, Horace Winchell. Sales 's contribution earned him the title "Father of Mining Geology" by the mining profession. The Butte Geological Department was considered an excellent postgraduate school in mining geology.

The field mapping system was simple and practical. Red lines for mineralization and blue lines for faulting were carefully and skillfully weighted using sharp pencils to emphasize proportionate widths and strength of mineralization and faulting. Disseminated mineralization was shown by red dots, and brecciation by blue stippling. Rock formations were represented by appropriate symbols. The resulting portrayal had both qualities of engineering accuracy and artistic expression.

A simple innovation was to get away from the use of bound notebooks, which engineers and geologists had used almost exclusively in the past, and go to a flexible looseleaf system in which each sheet upon which geological notes had been recorded could be filed properly, indexed and thus made available for use by the geologist who had originated the sheet, as well as by successors who followed and continued mapping the same area.

Underground mapping was done during the early part of the day and office work in the afternoon. Notes were transcribed and plotted by hand on plan maps and sections, thus creating the basic geologic record. The system included copying of additional maps for the mine superintendent's and foreman's offices. That way, the information gained from the geologists' observations could be graphically displayed so mine operators could use it. It was an effective way to coordinate geological and mining activity.

In addition, there was an excellent system of written recommendations. Driving of each development heading was based upon the recommendation of the mine geologist which then required the approval of the mine superintendent. Starting and stopping of each exploration and development heading was the responsibility of the geologist.

So it was a system based not on any high technology, but rather on good, hard-headed common sense and the development of a team approach so that mine geologists and operators worked together. That doesn't mean that they were always in harmony; there were disputes, but there was also an opportunity to take those disputes to a higher authority. It was a system that required hard work but had few flaws and it operated effectively.

Generally there was close rapport not only with the bosses but with the miners. In my opinion it was typified in the by-word between miner and geologist passing in a crosscut or drift: "How's she going? Did you find any ore today?" [laughter]

I think it would be interesting to start with a few of my first underground experiences. One of the first--and it was a very fortunate one--was to map a newly discovered ore body on the 500 level of the Diamond Mine. Upon my arrival in Butte I was assigned to be geologist for the Diamond Mine. My first day underground, I had the opportunity to see this beautiful face of high-grade chalcocite mineralization averaging between 30 and 40 percent copper across a width of about ten feet. It's hard to believe that anything like that existed. Yet in perspective, this was the type of ore that was found by the early- day prospectors when they had mined out the first silver showings and had gone down into the copper zone, finding abundant secondarily enriched chalcocite along the Anaconda lode. Those ore bodies were restricted in vertical range and occurred in a zone of strong enrichment usually several hundred feet in vertical extent. Below the chalcocite enrichment there was primary ore which generally averaged in the order of 4 up to 10 percent copper. But in mapping that high-grade chalcocite ore body on the Diamond 500 level, I was lucky enough to observe the last of the secondarily enriched high-grade ore bodies found in the Butte district.

Perry:

Shortly after that, I had an opportunity to participate in the last of the great litigations that characterized Butte 's history. The War of the Copper Kings is a well known event, and its glamorous phases and all of the things that went on during those clashes between the titans of the industry that met in Butte in the early days, were pretty much a thing of the past when I arrived in Butte, but there was one fight remaining. That was the argument between the Anaconda Company and Senator W. A. Clark over ore bodies in the Elm Orlu and Badger mines. The Badger was owned by Anaconda; the Elm Orlu was owned by Clark. Clark contended that because of the extra-lateral rights prescribed by the Mining Law of 1872, he could follow a vein from the Elm Orlu outcrops down into the Badger, and that since the Elm Orlu was the older claim, he had rights to all the rich ore Anaconda had mined out of the Badger and to its unmined deep reserves.

Sales, defending Anaconda, had taken the opposite viewpoint, and by beautiful mapping and very careful attention to detail, effectively demonstrated that what Clark was claiming as a lode was in fact a post-mineral fault, and that there was no extra-lateral right involved in this fault zone. I had an opportunity to go underground as an assistant to Sales and with some of the other geologists, particularly Chester Steele, who was the Badger mine geologist and had acquired a very intimate knowledge of the geology of that whole area. I was impressed with the excellent mapping done in support of the Anaconda case.

About that time, Clark produced some of his experts, and one of his professional men was William Colby, from Berkeley, from whom I had taken my course in mining law. It was quite a shock to me to be on the opposite side of a man I had respected as a professor of law. But later, as I had more and more contact with lawyers, I understood their professional attitudes; they can get themselves involved in situations on opposite sides that laymen have a hard time understanding or justifying.

But at any rate, that was a fine experience for me; I learned a lot about the importance of applying geology to the difficult legal situations involved in the interpretation of the 1872 Mining Code. During the actual court trial, I had the good fortune to be selected to handle the maps, so that I put the exhibits up on posters and charts before the judge, and in that way I saw firsthand how a court proceeding is carried on in a matter involving damages running into many millions of dollars. The case was decided in Federal Court by Judge Bourquin, and I found him an extremely interesting character. Sitting on the bench, he asked intelligent questions, and when his questioning was completed, he said, "Now, gentlemen, I'm going to go underground with you people, and we're going to go up in those raises and we're going to see these various points in which you are in disagreement." He said, "I'm going to decide for myself, although I'm not a geologist."

Swent:

And did he go down?

Perry:

He did go underground, and he corroborated Sales 's geology and gave his decision in favor of the Anaconda Company. The case was appealed in San Francisco Appellate Court, and ruled in favor of Anaconda, and the Clark properties were eventually purchased by Anaconda. So that was a fine early experience in my career of how you use geology in connection with the law, and the use of good, factual information in proving your point.

Swent:

Did you appear later in cases as well?

Perry:

No, that was my only experience, and, as a matter of fact, the Clark-Anaconda case was the last of the law suits in the Butte district. Sales has written a complete case history of all of those litigations in Butte. It's worthwhile to review critical points that are involved in the law of the apex. The concept of the code had its start in the early days of California mining where the miners were working on the Mother Lode and the geology was relatively simple. There was a quartz vein that carried the gold and that had an inclination or dip to it, and as it dipped away from the outcrop, it would in some cases dip outward under a claim that was owned by someone else. The miners in their local councils decided that the owner of the outcrop was entitled to the vein and that it could be followed downward even to the "center of the earth". It became a practice among the miners in California to adjudicate their problems on the basis of this simple law of following the vein downward even if it extended under a neighboring property owned by someone else.

In 1872, the law was codified by Congress formalizing the traditions and the customs of early-day mining in California because that was the best precedent they had. So Congress wrote into the law the right to follow a vein downward regardless of the ownership above the downward projection of the vein. Well, when you applied that to Butte, where Butte has such complex structural geology, where the veins are not simple, through- going features but often zones of branching, crossing, connecting, diverging fractures filled with copper ore and often faulted in various directions- -up, down, and laterally- -the complexity presented by that sort of situation made this law a very difficult thing to apply. It was little wonder there were disputes in Butte and unscrupulous operators could make illegitimate claims on ore that didn't belong to them. That's why there was so much divergence of opinion between highly qualified men. Not because they were essentially dishonest, but because in their own way they felt that they did have a position and that they could uphold it. So that you found experts, highly qualified geologists, on both sides, arguing vehemently against each other. And with some justification.

The situation exists to this day and I don't think there's any way to correct it. The law has been in practice for so long; the extra-lateral right is part of it, and the only way to operate with it is to follow the example of Anaconda- -it finally consolidated practically all the adverse ownership in Butte by purchase, settlement out of court, and actual court decisions. It worked to the advantage of Butte because it gave an opportunity to consolidate from an operating standpoint. Ventilation could be centralized; drainage and pumping could be localized in ways that produced the most efficient overall operation. I think it did a lot for the Butte district in that sense, but in the meantime, it's easy to understand why there would be some disgruntled claim owners who felt that they had been unjustly treated because of the leverage of the big corporation. In fact, the consolidation of properties enhanced the value of individual lode claims and many were sold at premium prices. The Mining Law of 1872 has been equally good for both the small miners and the big company because each, within its own limitations, has the right to locate a lode claim with inherent property rights on government land. It was a great experience for me to see all this and to participate in it at that early time in my career.

Swent:

You might tell a little bit about your living situation there.

Perry:

I came there as a bachelor and I had a room at a little hotel on Park Street. I ate at Fleming's boarding house, where several other young engineers took their meals. At the table there was a very lovely young lady who I found out worked at Hennessy's department store, was their leading model and ran the glove department for the store. I was so impressed with her, not only with her charm and beauty but also her very quick wit. Most of the boarders were men, and with her neat turns of speech she could handle all of them with one hand tied behind her back. I marveled at her humor, her intelligence, and at how well-informed she was. She came from a broken family; her father had moved to Canada and had taken her with him, and had put her in the convent in Calgary. The nuns had raised her as a little girl and she had been educated and trained by them. She came back to Butte and lived initially with an aunt and got a job at the Hennessy department store, which was considered one of the first-class department stores of the region.

Swent:

What was her name?

Perry:

Her name was Margaret Moore. Her father had come from Ontario, Canada, had mined in Butte, then gone up to Canada, had a ranch in Alberta, and had been successful in raising wheat there. He'd kept his one and only daughter in school at Calgary.

So within a year and a half, we were engaged and ready to be married. We were married November 16, 1926. It snowed about eighteen inches that morning and we had tickets on the North Coast Limited to go on our honeymoon to California. After the marriage ceremony at St. Patrick's Cathedral and the wedding breakfast at the Finlen Hotel, we were driven to the depot by one of my geological pals, but we couldn't get up to the Northern Pacific station platform because of the snow. This was my first experience carrying my bride. I had eighteen inches of snow to carry her through, from the freight depot a hundred yards or so to where the North Coast Limited was waiting. And I was thankful that I didn't drop her. [laughter]

Swent:

Who were some of your other pals at that time?

Perry:

I think one of my best friends was Alex McDonald. Alex was a member of the Geological Department and a Butte man, and a graduate of the Montana School of Mines. He was best man at the wedding, and afterwards, when I left Butte, he and his bride, Florence, bought all our furniture and our belongings that we weren't able to take into Mexico.

Perry:

Shortly afterwards, the great Depression started, and Alex was appointed to direct the Depression efforts of the Anaconda Company to take care of a lot of people in Butte, Montana. Despite the fact that corporations sometimes get the reputation for being heartless, I know for a fact that Anaconda through Alex took care of a lot of homeless, jobless people, feeding and sheltering them during those early days of the thirties and the company footed the bill for everything. Alex has told me many stories about the fine things that were done by the Anaconda Company during that period. Alex was the fellow that carried out the work; he ran the whole show; he had an organization under him and took care of a lot of people. Those were, of course, the days before there was any government help. In Butte, the Anaconda Company was the only organization that had the money and wherewithal to do a thing of that type.

Alex later became my assistant in Salt Lake City, and he did a great job in the developments that I'm sure we'll be discussing later on.

Swent:

What about the labor situation in Butte at that time? In the early thirties?

Perry:

We left Butte for Cananea in 1927 and the labor situation was fairly good at that time. In the early thirties there was a change. Wages were tied to the price of copper, and, of course, when the price of copper slumped to practically nothing, the miners took a terrible beating. There were layoffs and a lot of dissatisfaction and unhappiness, but there was nothing like the much more difficult situations that developed years and years later. At that time, I thought the miners generally, and the management pulled together pretty well.

I knew many of the miners, and we were friends and chatted together. As a matter of fact, I often wondered whether some of them were distant relatives of mine. That goes back to the start of our family in California, when, on my mother's side, her father and mother arrived here right after the admission of California to the Union. My grandmother was from County Galway, Ireland.

Swent:

What was your mother's name?

Perry:

My mother's name was Sarah Denis and her mother's name was Ann Mulhare. And she had cousins who, after the gold mines generally played out along the Mother Lode and things opened up in Butte, migrated there. But I hadn't kept track of distant cousins and didn't know whether I was related to any of the fine people I met in Butte. It was predominantly an Irish community, although there were also a lot of "Cousin Jacks" from Cornwall, Italians, Finns and other ethnic groups. But generally it was an Irish labor force.

Swent:

Kelley was one of the founders.

Perry:

Yes, Kelley 's family were early day miners in California who moved to Butte. He studied law--I'm not sure, I think it was at Michigan--entered the legal department of Anaconda and moved up through the executive ranks until he was chairman of the board of the company. He was an able man and a kindly, fine person. I was a great admirer of Mr. Kelley. I always thought he'd have made an excellent statesman if he'd moved to Washington, D. C. He had eloquence, ability, a keen mind, and high integrity--qualities we like to associate with political office.

In fact, men of such character were typical of Anaconda leaders of that period. John D. Ryan was the same type man. He was from Michigan, and he was chairman of the board before Kelley. James Hobbins was another man of the same caliber. It was a source of pride to have that kind of men heading the company.

Swent:

I have here some names: Al Taylor, George Heikes, and Justin Gowan. Do you want to mention them?

Perry:

Yes. Those were all young members of the geological department who made rapid progress with the company. The background of all this related to the expansion of Anaconda's mining activities abroad. One of the big moves that Anaconda made was the acquisition with W. A. Harriman of the very rich zinc and coal mines of Poland. Sales decided that a geological department was needed there, not only in connection with the execution of operating work, but also the probability of expanding ore reserves in that part of Silesia. So he selected Justin B. Gowan and George Heikes, young Butte geologists, and sent them over to organize a geological department in Poland modeled after the Butte department.

At Chuquicamata in Chile, Sales organized a department, first with Walter March and then with Al Taylor, both Butte geologists, in charge. At Potrerillos, Chile, the organization was similarly planned and Walter March was eventually moved to that office.

At about the same time, there were important discoveries being made at Cananea in Mexico, and Anaconda had a minority interest in the Cananea district. So Sales moved me to Cananea to establish a geological department there, modeled after Butte. Slightly later, Roland B. Mulchay, another young Butte geologist, was assigned to the geological department at Cananea.

This represented a major expansion of geological activity and of course the exploration work was carried out from those various centers rather than from Butte, along with the application of geology on a day-to-day basis in relation to the operations. So it was a very important move that enhanced the use of geology in mining operations.

Swent:

Sales kept his center in Butte?

Perry:

Sales kept his headquarters in Butte. Yes.

Swent:

And as a young geologist came in, he would be trained there first?

Perry:

He'd be trained there. All of them would be trained in Butte because having Butte experience in sampling, engineering and geology was considered most helpful and desirable. And, of course, there was an important department maintained in Salt Lake City. Paul Billingsley was originally in charge there and had a staff of men that covered the Park City, Tintic, and the Bingham Districts.

One of my first experiences, another thing that Sales gave me an opportunity to do after my first year in Butte, was to serve temporarily as an assistant to Tom Lyon, who was making a visit to many of the mining districts of Colorado for the purpose of stimulating the flow of zinc-lead concentrates to the International Smelter, a subsidiary of Anaconda at Tooele, Utah. We spent a month visiting most of the mining districts of Colorado, which was a liberal education for me.

Swent:

What about Dave Sharpstone?

Perry:

Dave was a Cal graduate who worked as a Butte geologist. Later he served as geologist at the Roan Antelope Mine in Northern Rhodesia.

Swent:

Were you at Mountain Consolidated] and Mountain View?

Perry:

Yes, after the Diamond Mine, I was assigned to the Mountain View and Mountain Con mines as mine geologist. Again, it was a very fortunate assignment because the geological department had designed an exploration crosscut from the Diamond Mine to cut the extension of the State vein, which was one of the principal sources of production at the Badger Mine. It was based upon the theory of a zonal arrangement of the minerals in Butte, where the central core of the district is generally richly mineralized with copper sulfides. Around it there is a halo of zine and subordinate lead; beyond that, silver and manganese. A crosscut was planned to reach out from the Diamond and cut the State vein in the copper zone.

The crosscut had been carefully laid out before I arrived in Butte, and my job was simply to keep track of it.

I remember going into the crosscut late one afternoon just before the miners were ready to blast, and seeing a face of the hardest, freshest, toughest "tombstone" granite you ever saw in your life, and deciding that somebody had made a terrible mistake, that there couldn't be ore in close proximity to granite as forbidding as that. The next morning, Eddie Kane, the mine foreman, called me up and said, "Vin, get up here and see what we have!" I went up to the Diamond and into that crosscut and immediately ahead of the very tough -looking, uninviting rock I had observed the previous day, the miners had blasted into a beautiful vein of high-grade bornite and chalcopyrite.

I learned right there that rich ore can occur without any significant alteration of the adjacent wall rock. That development was extremely important because its discovery on the 2600 level of the Diamond Mine--while it didn't have any great length on that particular level--represented the top of an important series of big copper ore bodies. By exploring on deeper levels in the adjoining Mountain Con Mine, the trend of those rich copper ore bodies was picked up. I was assigned the job of geologist in the Mountain Con so had an opportunity to follow this discovery right on down into some of the most spectacular high-grade ore that was ever developed anywhere. The ore shoots were in total over five thousand feet long and varied from ten to up to thirty feet wide. Grades sometimes went up to 6, 7, or 8 percent copper with average grade of about 4.5 percent copper. Later developments on the nearby Syndicate and High Ore Veins exposed similar spectacular copper ore bodies.

So it was another great experience. I wasn't in Butte long enough to see much of that development but at least I was there at the beginning. I left shortly after the Diamond Mine discovery to start work at Cananea, Mexico. But I heard from time to time about the development going on in Butte, and it was exciting.

Swent:

We were just talking about the fact that the mining community is such a small one and people who came from Michigan the "Cousin Jacks" from Michigan--went all over the country. You were starting to say something about going up to Butte.

Perry:

Many of the Butte miners came from Michigan, and the ideas that they brought with them, the skills and the ability to handle very difficult day-to-day underground mining problems, contributed a lot to the success that was achieved by mining companies in extracting ores under difficult operating conditions.

These impromptu remarks are simply, in a way, motivated by the fact that I had read Jim Boyd's interesting story about his activities in Michigan and the problems he faced when he took over, first of all, as a government representative, the efforts that were being made to help a sub-economic mining situation that existed at the White Pine Mine and make it a source for copper needed for our impending entrance into the Korean conflict. Later, Jim inherited all of this in a private capacity when he was asked to assume the role of president, and I believe chief executive officer of the White Pine Mine. He faced these things with a good deal of courage, skill, initiative and ability. The fact that under his direction the White Pine Mine didn't turn out to be a highly profitable operation was certainly no fault of his. Again, it reflected the difficult problem that the mining industry faces in undertaking jobs that require underground engineering skills, not only on the part of management but on the part of the individual miner, too.

That's one reason, I suppose, the mining industry has gravitated in recent years to large open-pit mining, because it's so much simpler and so much easier to do. While there are ore reserves close to the surface that can be tackled by these methods, that's going to be the trend for the immediate future. However, for the long-term pull, we must remember it is problems such as Jim Boyd faced at White Pine which will have to be solved in the coming centuries, if we are going to maintain a production of essential metals like copper.

Swent:

We had stopped yesterday just about the point where you were leaving Butte. I wondered whether there was any more that you wanted to say about Waldemar Lindgren. Was he a significant person in your life? Did you have firsthand experience with him?

Perry:

Only briefly in connection with the W. A. Clark -Anaconda litigation. He was one of the experts retained by Anaconda to testify during the court proceedings. We had a few contacts with him in a very informal, off-the-record way.

One of the most humorous ones, I thought, was the meeting early in the morning before the start of the trial. I, with several other Butte geologists, had worked most of the night on a model that showed the three-dimensional relationships between the Elm Orlu Mine and the Badger Mine, which were the bones of contention in the litigation. Lindgren appeared right after breakfast and carefully inspected the model, perhaps for fifteen or twenty minutes. The young geologists all stood around, somewhat in awe of Lindgren' s great reputation and the fact that all of us geologists had studied Lindgren' s writings and his well-known textbook on geology. So we expected some profound statement from him about the geological relations exhibited by the model. Finally he stood back and said in his broad Swedish accent, "Veil, boys, dat's quite a muddle." [laughter]

That really was about my only contact with Lindgren. He did make one remark at that time about Anaconda geologists. He was reported to have said that Anaconda was making a great contribution through its young geological staff in the ability to locate the position of veins and the faulted segments of those veins. But he said he wished that those young geologists would devote more time to the problem of what the veins contained and how they were mineralized.

Swent:

How did you make a model in those days? What were the materials used for a model?

Perry:

They were made of soft metals such as lead that could be readily molded. These forms were then affixed to a rigid frame and suspended in such a way that you could look through the maze of workings and see their three-dimensional aspects. Then the geology of each working was carefully inked in with pen and brush. Thus, the structure of the veins and the position of the faults were shown graphically so that the geometry was much more readily appreciated by the layman and, particularly, by the lawyers of the court and, of course, the judge sitting on the case. It made an effective presentation, and the Anaconda model, I thought, was much more effective than the model presented by the Clark interests, simply because the Anaconda model had all of the detailed geology that had been mapped with great precision using standard Butte methods, and thus provided an excellent three-dimensional presentation of the geological structure.

Swent:

Was this a standard thing to do at that time?

Perry:

Yes, it was, in connection with litigation work. Models were also used to some extent in presenting complex problems for geological study, but generally that wasn't the case. When you were presenting details of a structural relationship, you were talking to men that were well versed as mining engineers in the use of maps and sections. It wasn't necessary to make a three-dimensional picture for them. If, on the other hand, you had to make a presentation to a banker or a lawyer, models were of some real use. The use of the model in court and litigation activities was pretty much determined by the fact that you had to make your story clear and presentable to people that were not versed in the intricacies of engineering and geology.

Swent:

It seems to me that this is an entirely different skill; making a model would call on different talents.

Perry:

No, it really didn't. I think it was more a matter of ability to have good craftsmen. Actually, Anaconda maintained, during a large part of the litigation period, a model shop. One or two men were assigned to just that work and became extremely skillful in building these models. Some of the models have been preserved and given to universities. I believe there's at least one model, and perhaps more, at the Montana School of Mines, or Montana Tech.

Swent:

So these weren't built by the geologists themselves?

Perry:

Well, the men that worked in the model shop usually were geologists, because it was found useful to have men that understood the purpose and application of the model procedure and at the same time had the manual skills required to build the model itself.

Swent:

Is this still done in about the same way now?

Perry:

There's none of that being done now. In fact, the model shop in Butte was closed years ago, because the company had little use for models after the consolidation of properties following the litigation that ended with the 1926 Clark case.

Perry:

Well, should we start with the change from the cold wintry atmosphere of Butte to the beautiful sunshine of good old Mexico? [ laughs ]

Swent:

Yes, we should. How were you told to go to Cananea?

Perry:

Very casually. One day as I was bending over my drawing board working on a map, a shadow appeared behind me. I looked up and found the boss, Reno Sales, looking over my shoulder and handing me a little sketch that showed some heavy red lines beautifully drawn on a typical note sheet. On the note sheet there were a series of very high copper assays. He said, "Vin, would you mind just averaging the assays on this map and bring them in to me when you're finished?" I averaged the assays which, as I recall, showed somewhere between 15 and 20 percent copper with added molybdenum and gold values. I brought them in to Sales, and he studied them briefly, then looked up at me and said, "Would you like to see this kind of an ore body?" With an enthusiasm I had a hard time suppressing, I said I would be delighted. He said, "All right. Get your things organized, and you and I will start down to Mexico the day after tomorrow."

I went out that afternoon and visited the change rooms at the Mountain View and the Mountain Con Mines where I had been working, and gathered together my "digging" clothes. There was an early winter blizzard blowing across Butte Hill, and I remember the still -damp clothes began to freeze as I lugged them towards my home. I thought this was a real lucky break that I was leaving Butte at the start of the winter.

When I arrived in Cananea a couple of days later and started my work there, mapping not only underground but also doing a lot of surface geology, for the next thirty days there was nothing but beautiful blue sky and warm air, and I thought Mexico was one of the most delightful spots I had ever seen. It had a climate that not only equalled but, because of the altitude and dry air, was much more invigorating than the lovely California sunshine that I had been used to in my childhood days, [laughs]

Swent:

When was this?

Perry:

This was in October 1927.

Swent:

Were you already married?

Perry:

Yes, I was married and I took my wife en route to Mexico to Berkeley, to stay with my sisters and father who were living there at the family home on Le Conte Avenue where they had moved after the Berkeley fire.

Swent:

I see. She didn't go with you immediately.

Perry:

No, she didn't go immediately because I had no assurance that this was going to be a permanent job. We decided that because she was pregnant and expecting the baby within a few months, it would be better for her to stay under the loving care and attention of my two sisters.

Swent:

So that was an exciting time.

Perry:

It was a very exciting time, and it introduced me to a whole new geological world. In the first place, Cananea was an independent company, although Anaconda had a large stock interest in it. But the discovery of this very high-grade ore body had promoted a lot of competitive interest, and I suppose one of the important reasons for my being there was as an Anaconda representative, to determine just how important, economically, this new discovery would prove to be.