Oral-History:Plato Malozemoff

About Plato Malozemoff

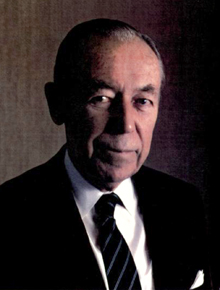

Plato Malozemoff is Chairman Emeritus and a Director of Newmont Mining Corporation and serves as a consultant to Newmont. He is a Director of Browning-Ferris Industries, Inc., of Houston. Mr. Malozemoff received a B.S. in Mining Engineering from the University of California at Berkeley and an M.S. In Metallurgical Engineering from the Montana School of Mines. He held various positions in metallurgical research, laboratory and field metallurgy, and in private gold mining enterprises prior to joining Newmont Mining Corporation as a mining engineer in 1945. At Newmont Mr. Malozemoff held several positions of increasing corporate responsibility until his retirement as Chief Executive Officer in 1985.

Among the honors bestowed on Mr. Malozemoff were an honorary D.Sc. in Engineering by the Colorado School of Mines and the professional degree of M.E. by the Montana School of Mines, both in 1957. In 1972 he received the AIME Charles F. Rand Memorial Gold Medal and in 1974 the Gold Medal from The Institution of Mining and Metallurgy (London). He received the Gold Medal Award of the Mining and Metallurgical Society of America in 1976. A Director and Member of the Executive Committee of the American Mining Congress, Mr. Malozemoff is a Distinguished Member of the Society of Mining Engineers.

Further Reading

Access additional oral histories from members and award recipients of the AIME Member Societies here: AIME Oral Histories

About the Interview

Plato Malozemoff: An Interview conducted by Eleanor Swent in 1987 and 1988, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1990.

Copyright Statement

All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Plato Malozemoff dated February 1, 1988. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved Plato Malozemoff until May 1, 1995, and thereafter to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley.

Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the Regional Oral History Office, 486 Library, University of California, Berkeley 94720, and should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user. The legal agreement with Plato Malozemoff requires that he be notified of the request and allowed thirty days in which to respond.

It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows :

Plato Malozemoff, "A Life in Mining: Siberia to Chairman of Newmont Mining Corporation, 1909-1985," an oral history conducted in 1987 and 1988 by Eleanor Swent, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1990.

Interview Audio File

Interview

INTERVIEWEE: Plato Malozemoff

INTERVIEWER: Eleanor Swent

DATE: 1987 and 1988

PLACE: Berkeley, California

A LIFE IN MINING: SIBERIA TO CHAIRMAN OF NEWMONT MINING CORPORATION, 1909-1985

I THE RUSSIAN PERIOD AND EMIGRATION TO THE UNITED STATES

(Interview 1: 2 December 1987)

Swent:

Mr. Malozemoff, suppose we start with a little bit about your father, and if you want to go back to your grand parents, you can begin as far back as you like.

Malozemoff:

I knew very little about my grandparents, but my father, of course, I knew well, and he was an extraordinary person.

Swent:

Alexander was his name?

Malozemoff:

His name was Alexander Platonovich.

Swent:

So your grandfather was also Plato?

Malozemoff:

Plato. That's right. The interesting thing about that is that for some generations the first born in the Malozemoff family was successively Plato or Alexander. So that's how I became Platon Alexandrovich. My father was Alexander Platonovich, and his father and my grand father was Platon Alexandrovich. My father apparently had a very good education in St. Petersburg, and his education encompassed not only the professional interests that he pursued early in his life, as an engineer, but also a wide variety of subjects. Under the old system of education in Russia it was mandatory for anyone to enter university to be interested and to have courses in Latin and Greek. My father studied both Latin and Greek, and because of his absolutely extraordinary memory, he could recite Ovid's poems at fifty years of age, in Latin, and the same with Greek. In the course of that education, of course, he was interested not only in those languages. He also learned French, and he learned German, and he was interested in philosophy, in economics, and music and art. He was a true renaissance man in that sense. So his education prepared him, I think, for comprehension of the world and all its complexities. Part of his success in life and attractiveness was because of this varied education which he used with comprehension, interest and enthusiasm.

He persisted in being interested in languages. For example, when in the late 1930s he and I organized a partnership to start mining business in Latin America, he started learning Spanish, which came rather easy to him because of his remarkable memory, but also because of his knowledge of French and Latin. The interesting thing about his linguistic abilities is that his pronunciation of all languages, except Russian, was terrible. On the other hand, he could write grammatically, and he spoke pretty well, quite grammatically, but it was difficult to understand him in foreign languages because his accent was so pronounced.

Swent:

Russian was the language that he spoke?

Malozemoff:

Right. Russian was his native language. His knowledge of French was quite comprehensive. He knew more Spanish than I did, but sometimes I had to interpret his Spanish into the Spanish that other people understood, because his pronunciation was so poor. Nevertheless, anything that he ever studied or read, he seemed to remember in detail. I could talk to him about novels that I read of Sinkiewicz, the great historical novelist of Poland, and he could recall most of the events in any one of his novels that he had read. One of the things that fascinated him was the history of China in the 1920s and earlier. In the internecine struggles of the '20's, he knew the name of every overlord and every general, and he could describe the conflicts that they had and who won the battles and who didn't. His memory was absolutely phenomenal.

Swent:

Would you explain the social ranking in Russia at that time?

(The following section was written by Mr. Malozemoff after the interview)

Perhaps I should begin with earlier progenitors. My grandfather was a Russian military officer stationed in Warsaw, Poland. He was apparently a happy-go-lucky person, a very attractive man. He became enamored of a very beautiful daughter of a Polish officer and married her. They had six children: one son, Alexander, my father, second born; and five daughters, Natasha, Maria, Lida, Olga and Sonya, in that order of their age. The Malozemoff s had a privileged social status, "dvorianye," a social ranking just below the aristocracy. The root origin of the word "dvorianye" in Russian is "dvor," which means a yard. In other words, real estate property that was usually granted by the Tsar for special merit. The closest English translation of "dvorianye" is landed gentry. However, as far as I know, the family had no real estate property, probably having lost it in some prior dim past.

The family was prosperous enough to have all six children finish the university. As a child I met all of the sisters except the oldest, Natasha, my father's favorite sister, also greatly admired by my mother. Olga was an accomplished pianist, later to become a professor of piano in Leningrad Conservatory of Music, where before the revolution, when it was known as St. Petersburg Conservatory, my grandfather's sister Sophia also was a professor, formerly a pupil of Anton Rubinstein, a famous Russian pianist and composer.

This musical tradition in the family inspired my father to take up the study of violin, which ultimately led to his joining a class at the St. Petersburg Conserva tory conducted by the greatest modern teacher of the violin, Leopold Auer, who taught pupils who became the greatest virtuosos of modern times: Mischa Elman, Jascha Heifetz, Efrem Zimbalist, Nathan Milstein, Michel Piastre and many others. After the revolution, Auer emigrated to America and taught for some years in Boston. The training that father got and also the inspiration he gained from Leopold Auer he carried all his life. I suppose that inspired him to insist that I take up the violin as well.

I'll never forget one story that he told me about Mischa Elman, who at the time was studying violin at Leopold Auer's conservatory classes. He was only ten or eleven years old. He was an extraordinarily gifted boy, and he advanced to the point where he was studying a Paganini concerto. In the first Paganini concerto there is a passage where double stops in tenths are played, and the tenths on the lower positions of the violin require a long stretch of fingers. Here was this young boy with a small hand that could barely do this. My father recalled to me one lesson at which he was present these were group lessons where Mischa Elman was asked to play the Paganini concerto. But apparently the pain that he suffered in playing these tenths was so intense that he could only play it and at the same time cry.

However, my father decided to choose an engineering profession and graduated from the Mining Academy in St. Petersburg with specialization in iron and steel smelting. He also attended the famous Freiberg Mining Academy in Germany to perfect his studies. There he met a student, a Baltic Russian-German, three or four years younger than he by the name of Herbert Kursell. This is significant because Herbert Kursell joined the American Smelting and Refining Company in the 1920s, and he and my father did a number of things together in America. What Herbert Kursell did for me was also of some significance in my life. Herbert Alexandrovich was Kursell 's full name. His family and my father were very, very close friends in America.

On returning to Russia from Germany, father became active in the Social Democratic Party, which was opposed to the Tsarist regime. He practiced briefly at an iron and steel works in the Ural Mountains, where he courted a strikingly beautiful, tall sixteen-year-old daughter of the manager and proposed marriage. He was then twenty-five. The manager's wife, an imperious woman, opposed it because she thought her daughter was too young, and anyway she didn't think much of father because he didn't have a significant status at that time. She prevailed on the governor of the province to have my father fired and expelled from the province. Nearly twenty- five years later he divorced my mother and married his first love in the United States after bringing her out of Russia.

Shortly after his escapade in the Urals in 1907, he was arrested in St. Petersburg for distributing political propaganda against the Tsarist regime and sentenced to one year in prison and ten years of exile in Siberia.

(Return to interview transcript)

Malozemoff:

It might be worth relating a curious not necessarily very significant but amusing attempt to reestablish the genealogy of the Malozemoff family by my then maiden aunt, father's sister Olga. Apparently before the revolution I have this story from my mother she reconstructed the genealogy of her forebears. How much romance and how much truth there is in this I don't know, as this is third-hand information.

At any rate, her research into genealogy particularly interested her because of her mother that is my Polish grandmother. Apparently her family was derived from the French Huguenots who were banished from France and fled all over Europe. Some of these French Huguenots settled in Poland.

She tried to trace the French connection and concluded, or perhaps my mother invented it I don't know that the French family from which my grandmother descended was related to the Due de Guise, who is a historic figure especially well known by the tourists who visit the Chateau de Blois in the Loire region. When the Huguenot rebellion broke out, he was sympathetic to the Huguenots and lived in the Blois Chateau. The chateau was invaded and he was murdered in one of the rooms. When my wife and I visited this chateau in 1948, there was a small portrait of him on the wall near where he was murdered. She never believed the story of the genealogy, but when she looked at this portrait, she said, "My God, he looks exactly like you! Maybe there is something to that story." (laughs) He lived three centuries ago so I doubt that there is anything but coincidence in the likeness. Well, whatever the truth was, Olga was very proud of that background.

Swent:

You have never gone back to Russia?

Malozemoff:

Never have until October, 1988. However, my wife made a trip to Russia with her brother ten years ago. My son Alex was there seven years ago, and again in 1988, both times for IBM.

(The following section was written by Mr. Malozemoff after the interview)

Mother and her Family

Both my grandmother Pelageya and grandfather Andrew were born peasants and were emancipated peasant serfs. My grandmother was illiterate but very talented and was a well-recognized designer and seamstress of ladies' clothing. She established a large shop with several seamstresses working for her in a large apartment on the second floor of 30 Mokhovaia Street in St. Petersburg. Among others, she made dresses for ladies-in-waiting at the Imperial Court, and with substantial earnings raised four sons and three daughters (Alexander, Sergei, Paul and Constantine; Mary, Vera and my mother, Elizabeth) and gave all a university education. She was a tiny woman, very energetic and strong, wise and intelligent, very human and loving to her children and grandchildren. My grandfather, a typesetter in a printing shop, died early, probably because he drank too much a common cause of death in Russia.

Grandmother's end was a sad one. In the summertime, back in 1918, she and two of her daughters (my mother was then in Siberia) went for their vacation to an estate in the Ukraine which was managed by one of her sons, Sergei. Olga DeSelecky, who owned it, had a daughter who married my uncle Alexander, the father of my first cousin Xenia, now living in Holland. The DeSelecky family was in Europe, and they offered Sergei the opportunity to have his family come there and spend the summer vacation. They did this for a number of years.

This was during the demobilization of the Russian armies shortly after Russia concluded peace with Germany in the First World War. Actually, the armies were not demobilized, but they gradually disintegrated and soldiers roamed high and wide. Most of them were originally peasants. One night a group of renegade soldiers not from the region invaded the house where the female family of my mother was then vacationing and murdered all the women and killed Uncle Sergei. Three children belonging to one of the sisters were with them, and the eldest, a boy, escaped by jumping through a window and was shot at. But they missed him, and he ran away.

His twin sisters, who were only about five years old, were hidden by their mother under a sofa, just before the intrusion, and the soldiers never found them. And these poor girls stayed in the room with the dead bodies and pools of blood all night before they were rescued next morning by neighboring friendly peasants. This affected their minds so that they were somewhat unbalanced. Later on one of the twins died, and the other, with her older brother, were brought out from Russia by my mother and lived with us in Oakland, California. She was a nice girl but she never lived down that experience. She was a good tennis player and had a clerical job with Pacific Gas and Electric. She died three years ago in San Francisco. Her brother died during the Second World War from pneumonia as a result of his being an interpreter in inclement weather on the Russian ships that came to San Francisco harbor.

My mother was a very lively young girl, highly romantic, verging on sentimental, which she remained all her life, and anxious to learn everything she had time for. As was the custom in those days, she studied piano and French, which she spoke fluently. She enrolled in a German high school because it had the highest scholastic reputation and became fluent in German. After finishing high school, she enrolled in a special teachers' college established by a noted educator, Bestuzhev, where she prepared for a teaching career. While studying there she tutored the children of the Nobel family of the famous Swedish Nobel prize.

She did not quite finish her education because she became interested in the political movements in 1906, 1907 and 1908. She met my father at that time. He was quite an active Social Democrat that was a small party against the Tsarist regime that wanted to install a democracy. My mother, who was in effect his helper and secretary for these political activities, fell in love with my father, and they were married actually in prison just before he was sent out to exile.

(Return to the interview transcript)

Swent:

Some of the things I have read indicated that teaching at that time, especially if you taught peasant children, was also considered a politically subversive activity. Was this so?

Malozemoff:

I don't believe so. There may have been some restraint on liberal teaching, but I don't think my mother was really involved in that, nor in any way affected by the political prejudices.

Swent:

She didn't look on her teaching as a political activity, then?

Malozemoff:

No. No, her later teaching in Siberia was essentially in the lower levels, in the grade school level, and then the high school level. So it didn't get into the level where people usually begin to think about political problems as they do in the universities throughout the world.

Swent:

Perhaps this might be a time for you to mention some more about meeting your wife and her family, and also of your contacts with your Russian family. You still had an uncle, you said, who lived in France, and your father, when we last heard of him, was in France.

(This section was written by Mr. Malozemoff after the interview)

No, my uncle Paul did not live in France, but my father lived in Cote d'Azur, near Nice, for only a few years while recuperating from a serious operation. However, uncle Paul did come to France in 1927 while we were there to visit my mother for a day. He was then working in Moscow with my father for the Lena Goldfields concession.

During the 1920s and 1930s my mother kept in touch with uncle Paul by correspondence and also with my father's oldest sister, Natasha, of whom she was very fond. Father also corresponded with Natasha and his mother until the Second World War, and, of course, visited with them and some of his other sisters' families during the Lena Goldfields concession period, 1924-1929. After the war all correspondence ceased by the Soviet Government discouraging its citizens' contacts abroad. Father died in 1944, and mother was never able to reestablish any contacts with any members of the family in the Soviet Union after the war.

However, in the early twenties, we learned of the departure in 1917 from Russia of my eldest cousin Xenia (now 94 years old), daughter of my mother's eldest brother Alexander. She married at sixteen years of age a much older man, a Dutch citizen, Jan Gellen, and left Russia with him to go to Finland and later to Poland. They had four boys, and her husband died in Poland during the war. After the war, with the help of her Polish relatives, she moved to Holland, where she bought a house, and on a Dutch pension and occasional help from Polish relatives, she raised the four boys. The eldest, Alexander, is a civil engineer now retired and settled in New Zealand where he practiced his profession. The other three sons are in Holland, one of whom lives with his mother in Tilburg. Xenia, despite her age, corresponds with us regularly, her handwriting showing no deterioration due to age. We visit her when we are in Europe. She was a great beauty when young and is now vivacious and cheerful, reminding me of mother's similar qualities.

The other members of our family who settled abroad were the Smoliakovs. In 1918, the mother of that family, Maria, my mother's elder sister, was killed along with my mother's other sister Vera, and my grandmother, to which I referred earlier, but Maria's three children escaped and rejoined their father in St. Petersburg. Their father and the children had a terrible time during the civil war and the famine that ensued. Some of the stories that their father told were really horrendous. One of the girls died. I don't know how they managed to survive during the famine. Their father was a lawyer and was very impractical. He didn't know how to cook and he didn't know how to take care of children, but somehow they survived, perhaps with the help of their new stepmother, whom their father married then. My mother first brought out the two remaining children to live with us and then brought out their father and his second wife. These were our only close relatives who emigrated from Russia. All the rest of the surviving relatives stayed in Russia.

In October 1988 my wife and I were in Russia for two weeks on a tour, and our son was attending a scientific conference on superconductivity in the south of Russia. He was there on behalf of IBM (he has been working for them in their research department for nearly twenty years) and delivered a talk. A Russian scientific magazine reported on the conference and mentioned his name. A young scientist called this name to the attention of his friend whose grandmother was a Malozemoff . This young man's sister, an actress in the Moscow Art Theatre, wrote our son Alex at IBM, identifying the names of her grandmother Natasha and her sisters, as well as their brother, who was my father. The letter said that if these names meant nothing to Alex, he need not read any further and could throw the letter away.

This first contact after forty-five years of total silence which could have been interpreted as meaning that none of the family survived was naturally tremendously exciting, and there followed very active correspondence by Alex and me with various members of our numerous family in Russia who were identified by the actress Natalya Orlova. A first cousin of mine, Alexander Gulyaev, the son of my uncle Paul, mother's brother, was the only one of my generation whom I remember meeting in Russia as a child. He is a year older than I and is a well known and respected ferrous metallurgical scientist. His father was a ferrous metallurgist who later (before the revolution) became manager of a steel works in the Ural Mountains at Lysva. Alexander or Shura, as he was called more familiarly, has some thirteen books and several hundred technical articles to his credit, which I learned of from his letters to me. He also confirmed the knowledge I had from a friend of my brother, who as an officer of the occupying American army in Berlin, met in 1946 Alexander Gulyaev, a lieutenant colonel in the Russian army the only thread of information indicating that at least one of our relatives had survived. However, owing to the Soviet freeze on contacts with relatives abroad ,_ that incident of recognition was not followed by any correspondence.

Through Natalya Orlova we identified another family, Shaskolsky, who were descendants of another of my father's sisters, Maria. The head of the family is a son of Maria and my first cousin; he is a noted historian and professor at Leningrad University, and so is his wife. His son is a specialist in American history and has been in the United States several times. Altogether, Orlova has written us that she can identify about thirty members of my father's and mother's families in Moscow and Leningrad which is not surprising considering that my mother had six brothers and sisters and my father had five sisters, and that a fourth generation of descendants is now growing up.

In May of 1989, my wife and our daughter went to Russia for eight days, and they spent one day with Shura Gulyaev and Natalya Orlova; they found them to be charming, friendly, most interesting, and very intelligent. They did not wish to speak of perestroika, which is a sensitive subject for all intellectuals in Russia. In Leningrad they dined with the Shaskolsky family and were also received by them with open arms.

After these visits, Shura Gulyaev and Natalya Orlova expressed great interest in visiting us in the United States never having been outside the Iron Curtain- and seeing something of this country. I am now making arrangements to make this possible.

My wife came to America about three years after we did. She came from Harbin, Manchuria, with her brother, mother and father.

Their original abode was near the Volga River in a little town called Urzhum, near Kazan, in central Russia. Her father came from a wealthy family that owned vast timber lands which they eventually lost. He became a self-made man and prospered as the owner of a department store. He did not believe the revolution would disrupt the way he and his family lived or everything that Russia had lived by.

At any rate, when the purge of the more prosperous owners of businesses began in 1918, he and a number of others decided to hide out of town for a while in the hope that the situation would blow over. It didn't, and eventually they had to flee to Siberia. Because the Trans-Siberian Railroad was blocked by civil war between the Red and White Armies, he made his way by foot from European Russia, arriving eventually in the Manchurian town of Harbin. It took him something over a year to do this. Most of his walking was done during the night to avoid the warring troops. He spent some nights in peasants' cottages and some out in the open. He walked south of the railroad, which is located in central Siberia. The winters are very severe there, and how he survived during the winter is hard to understand.

His wife and two children stayed on in Urzhum, where she worked and the children attended school. For over a year they did not know if the father was dead or alive. Finally they got a letter from friends from Irkutsk with one word in the father's handwriting. In Harbin he found work and finally communicated with the family, asking them to come and join him there. By this time the Trans-Siberian Railroad was open, and they travelled by train to Harbin, but the trip took over a month because of interruptions in service and frequent stops for searching of the passengers and their baggage .

In Harbin, where the family settled for a while, the children went to Russian schools. By agreement with the Chinese made in a previous century, Harbin was the headquarters for the Trans-Siberian Railroad and had a large Russian population. Within a year, and before the communists took over Harbin, the whole family emigrated to the United States in July, 1923, and settled in San Francisco.

My first acquaintance with my future wife had a curious origin. I knew her brother, Anatol Harlamoff , and my brother knew him even better; we were then attending the University of California, and he and my brother often sang informally at parties.

(Return to interview transcript)

Swent:

And your brother's name?

Malozemoff:

Andrew. We had a very good friend who was a doctor, a woman named Lordkipanidze a wonderful woman and a good doctor. She knew many people in the Russian colony, and knew my wife's family well. On one Sunday she was having lunch with us at our home, and both my brother and I were there. We were talking about this and that, and eventually the conversation turned to girls .

Both my brother and I contended that Russian girls were sloppy and unattractive. They didn't know how to do their hair, they didn't know how to dress; generally, we felt that American girls were better groomed and so many were pretty.

Malozemoff:

We started naming a few Russian girls we knew and then she said, "Well, I'll make a bet that I can introduce you to a Russian girl who has absolutely the opposite image from the one you are describing." We took up that challenge.

She arranged, together with my mother, for a party at our house and invited Alexandra Harlamoff and her brother to it. The brother came, but Alexandra did not; she disapproved of the whole idea of being invited by some boys so they could look her over. So we had the party without her.

Her mother apparently knew something about our family without ever meeting us, however, and she suggested to her daughter that it would be all right if these boys were invited to her party when she gave one. Some months later we got an invitation, and both my brother and I went. I may say here that my brother was a very good-looking boy and well liked by girls. He had an easy manner with girls and was popular with them, whereas I was more reticent, and not as good-looking either. At any rate, Alexandra and her mother, her father by the way had died earlier, were living in an apartment in San Francisco, on the second floor. As we came up the stairs to their apartment, Alexandra came out to the upper landing and looked down at the Malozemoff boys. For some reason she decided she favored me, and that's how our acquaintance started.

She was very intelligent and attractive, a marvelous ballroom dancer, and very popular in the Russian colony. She had several beaux. Our courtship lasted for a long, long time because I felt it would be unfair to her to marry until I had an income of at least $500 a month. At that time I was getting a very low income as an employee of Pan American Engineering Company starting at $120 a month and later increased to about $250 a month.

(The following section was written by Mr. Malozemoff after the interview)

Mother rejoined my father in Siberia in 1908 at his place of exile in Barguzin, a small, remote town in a region just east of Lake Baikal. She* went back to St. Petersburg in 1909, where I was born, and when I was six weeks old she took me back to Barguzin. Part of this journey involved several days on horseback in the winter snow while carrying me in a sling around her neck. My brother Andrew was born in Barguzin a year and three months after me. She took us back to St. Petersburg about every two years for a visit of a month or so with her mother up to the last time in 1917, just after the February revolution, when the Tsar abdicated. These trips were very arduous and took two to three weeks, and in the earlier years required travelling for several days on horseback to reach the remote Siberian town where we lived in very primitive circumstances in a log cabin.

My mother taught privately and in effect supported father because as an exile, he was out of a job. Those years in Barguzin were extremely difficult years for the family, but somehow they made it. There were no resources from the Malozemoff family to help my father because they were not that affluent. He had to make his way the best he could. They lived on the very small earnings that my mother had and somehow managed all right.

The interesting thing about that period and this comes from my mother ' s remembrance was that there were many other political exiles in Barguzin with whom they made acquaintance. Most of them were very intelligent and highly educated people of the class we used to call in Russia 'intelligentsia. 1 What amazed them, and I think is even more amazing to us today, is that they had freedom of movement, freedom of thought they could think about anything and talk about anything; they could read anything they wished, bring in any books they wanted, whatever their political nature. There was scarcely any restriction, except, of course, they had to remain in Barguzin.

(Return to interview transcript)

Malozemoff:

We have a photograph that I remember, and it's somewhere in my files, a picture of my father and mother and several of their friends on the top of a mountain, where they had a picnic. The title they gave to this picture is "How wonderful is the world, and how free we can be as exiles under the Tsarist regime."

Swent:

You say your mother did not mention this freedom in her memoirs?

Malozemoff:

No, nor these people, nor this particular photograph, of which she was very proud. She used to show it to me, and the title I cited was written on the photograph in her hand.

Swent:

Were there also people who were actually fettered in chains while in exile?

Malozemoff:

No. No, I think that's a mistaken notion. They were fettered in chains while they were in prison, but as soon as they reached the assigned place of exile, they were free of chains, and they were free to roam, take jobs and there was no restriction as to what jobs they took, if there were any jobs to have.

Malozemoff:

Well, sometime in the third year, my father, being a mining man, learned of the gold activity that was going on and of the mines that were operating in that general area. One particular mine, which was quite successful, was owned by a man named Jacob Friezer, whom I believe my father may have known in St. Petersburg before exile. At any rate, somehow he made the contact with him, and Friezer invited him to manage this mine. He had no problem in getting permission to accept the post of mine manager, and the government authorities allowed him to move from Barguzin to Korolon, some two or three hundred miles north of Barguzin. Mother describes the life they had there, which was in, again, very limited circumstances Their living place was very modest and they had to do everything themselves. She was actually the treasurer of the company, because they had very few employees. At any rate, it was a successful operation and father managed it very well, apparently, producing both gold and profits. Despite modest earnings, we had a teenaged Yakut girl as a servant, Marisha by name. She was uneducated and very naive, and she enjoyed playing with my brother and me despite the discrepancy in our ages. We liked her a lot.

Swent:

Who were the miners? Were they prisoners?

Malozemoff:

No, the miners were mostly free people belonging to the local Asian tribes. The local tribes there were Yakuts; they were of Mongolian origin, something like Eskimos. They made good miners; they were good workers but they were completely uneducated so that whoever ran the mines had to teach them everything.

These mines, by the way, were drift mines. A drift mine is an underground mine that exploits gold from placer deposits. Placer deposits are those deposits that are formed usually in old river beds as a result of the erosion of rocks containing gold bearing veins. Gravels and gold from this gradual erosion finally finds its way into the streams, and by the action of the water the gold gets concentrated in the bottom of the streams. Consequently the richest part of these placer deposits is usually just above bedrock and overlaid by fifty, sixty, sometimes up to two or three hundred feel of gravel, Thus a drift mine is actually an underground mine that recovers the high-grade streak of gold occurring at the bedrock level. It's a hazardous type of operation because gravel is loose it's not consolidated. In Siberia, there is sometimes permafrost, and therefore the gravel can be solid but at any rate there's always the presence of water that has to be pumped, except where rivers took new courses, leaving the old river beds dry. But that's a fortuitous occurrence, and in any event it's a complicated operation. In those years it did not require any sophisticated equipment because local timber was used to support the loose gravel. In permafrost, once it was thawed, it could actually be mined by picks and shovels. They didn't use explosives underground or any other mechanical equipment. It was all hand work.

Swent:

Did they have shafts and hoists?

Malozemoff:

Yes, they had to have shafts to get access to the bedrock, and they had hoists which were mechanized by steam engines or electric motors. The Korolon mine which my father managed was a simpler type of mine; it was entered by a tunnel and it required no shafts or hoists.

Swent:

And the men, as I understand it, were paid according to how much gold they actually mined?

Malozemoff:

That varied. In some instances they were paid on contract for so much gravel mined, and at other places it was just straight wages. But the contract system gradually spread throughout Siberia and was fairly universally used. This was the case with placer mines in the Yukon and in California also. A lot of the gold was stolen and never got to the company's coffers, so the security that had to be imposed was one of the important elements in making an enterprise successful.

Father stayed on as manager of the mine in Korolon for some three years. The fact is, the mine was successful partly due to his technical and organizational skills and partly due to his ability to control the stealing of gold! Anyway, his reputation began to be widely known in that particular area, and he received an offer to come to the biggest gold mining camp in the whole of Russia, near Bodaibo and the Vitim River. It belonged to Lena Goldfields Company and was controlled by a British company named Selection Trust. He accepted the offer to manage one of the mines in 1914, and moved his family to the Lena Gold- fields camp.

Malozemoff:

The first mine he managed, Prorok-Ilyinski, was probably the poorest one.

(The following section was written by Mr. Malozemoff after the interview)

It would seem appropriate at this juncture to describe the operations of Lena Goldfields. In 1981 I was given from the archives of Consolidated Gold Fields PLC in London a four-volume report written in February, 1914, by C. W. Purington, their consulting engineer, on the basis of which they were to decide whether or not to keep their 25 percent investment in Lena Goldfields. (They eventually sold it.) Purington was known to my father, and he had great respect for him. I suspect father had this report and implemented some of the recommendations contained in it. I may mention that Lena Goldfields broke into world news in 1912, when a general strike was suppressed by an army contingent and about 200 workmen were killed by rifle fire during a demonstration.

To get back to Purington's report, he recorded that at the time of his visit to Siberia, June 28 to September 13, 1913, he devoted fifty days to the examination of the Lena Goldfields operation and twenty- five days to another property owned by another company.

Gold was first discovered in the region north of Lake Baikal in the Homolko River in 1843. From the time of meaningful production, 1863 to 1911, the total gold produced from Olekma district was about 17,600,000 ounces, and about one third of this was produced by Lena Goldfields,

In 1913, when Purington made the trip to the mines, he travelled by horse-drawn carriage for six days to cover 275 miles by road from Irkutsk, the capital of Siberia, to a Lena River port, Zhigalovo; thence, from Zhigalovo downstream by boat to Ust-Kut for 220 miles; down the Lena from there on a side-wheeler steamboat to Vitimsk at the confluence of the Vitim River flowing from the east to the Lena River, a further 480 miles; and from Vitimsk to Bodaibo up the Vitim River for 154 miles. Rivers were open to navigation between June 1 and September 28. The boat trip required four days, and the total trip of 1,130 miles took ten days. From Bodaibo to the mines there was a narrow gauge railroad of some thirty to forty miles.

The climate at the mines was not too severe. The average temperature in April was 30F., in May 5 OOF., in June and July 65, in August 52, September 35O, October 10, November minus 22, December minus 28, January minus 15 to minus 38, February minus 10, and in March minus 8 to plus 5F.

Most of the placer mines worked were drift mines, that is , underground mines in which the rich bedrock streak, about five feet ten inches to seven feet thick and some 100 to 120 feet below the surface, was mined and ground supported by timbering. In most mines the deep river gravel beds were frozen by permafrost; they were thawed initially by charcoal fires and later by the Alaskan technique of steam injection points. The width of the pay streak was 140 to 200 feet, and the gravel was mined in twenty-eight by twenty-eight-foot panels. There were a few mines shallow enough for surface mining.

During Purington's visit, eight mines were operated. Owing to the use of wheelbarrows for underground haulage, individual mines had multiple shafts to reduce the distance to a maximum of 600 feet between the working face and the hoist that lifted the gravel to the surface. At the surface the gravel was transported to the washing plants on a rail track by horse drawn cars and by four small electric (30-62hp) and four steam locomotives (15-40hp) . A total of some 1600 horses were used, 540 of these in washing plants, hauling tailings away.

Much of the gold was coarse and contained numerous nuggets. Some nuggets had unusual shapes; father gave mother a pin made from a nugget about three-quarters of an inch long shaped like a miniature bunch of grapes. She also had a bracelet of gold nuggets, each about one- quarter inch in size. These are heirlooms I still have. The biggest nugget found in the mines weighed five pounds.

A modern electricity generating plant using wood for fuel permitted electrification of the townsites and lighting underground, as well as power for centrifugal pumps to remove water from the mines , for hoists , and for the washing plants.

The individual mines had a relatively limited life of three to eight years, but placer gold deposits in old river channels abounded and new mines were continuously being developed to replace those depleted. The average grade of the gravels mined for some fifty years was about 0.20 oz. per cubic yard, which yielded $12.20 per ounce net or $2.94 per cubic yard. I don't quite understand this low figure, as the gold price at the time was $20.67 per ounce, but it may have been net of royalties and taxes imposed by the Russian government. Some of the mines were higher grade than this average. One area on Nakatami Creek averaged $15.50 per cubic yard from 1868 to 1878 and produced 1,068,000 ounces during that period.

The total payroll was 8,000 men, many with families. Surface labor worked ten hours a day, underground labor eight hours a day, but reduced to six hours a day for especially arduous work. Days of rest were four per month, Overtime was paid at one and a half days' pay. While there were no labor unions, labor was hired under a well- defined contract expressing the obligations of labor and employer for all foreseeable and even unforeseeable circumstances. Hence labor was free and not indentured nor the kind of prison labor that was employed in vast numbers during Stalin's regime. Living quarters for single as well as family men were free, as well as medical care. The underground mine pay was for so many cubic yards of gravel excavated by pick and shovel, but if a set minimum was not achieved, the minimum day's wage was 1.68 rubles per shift at an exchange of 1.89 rubles per U. S. dollar.

Some comparisons with comparable American gold placer drift mining practices in 1913 are of interest:

Lena Fairbanks Goldfields Alaska Nome

Cost/cu.yd. $6.30 $4.50

Cost of labor/shift 0.90 7.50

Productivity, 1.3 to

cu. yds. /shift 0.75 5.90 4.0

Some of the costs were extremely high, notably the freight costs, which, because of the remote location, were from 180 to 2,000 rubles per ton. The highest portion of the cost was the wagon transport cost from Irkutsk to Zhigalovo, the port on the Lena River, a distance of some 275 miles. An especially high cost was the transport of heavy pieces weighing ten to twenty tons, which cost 1,000 to 1,800 rubles per ton nearly prohibitive.

Gravels were washed on the surface in seven trommel plants and nine sluice plants, which washed about 5,000 cubic yards per day at a cost of 0.45 rubles per cubic yard. The washing season was only 160 days, but the mines were worked all year; consequently winter production was stockpiled in dumps of up to 90,000 cubic yards each. They froze during the winter and had to be thawed in the spring with steam points before being hauled to the washing plants. There were five miles of track installed for the principal mine and washing plant at Nadezhdinsky . The washing plants required 1,700 men per day. The cost of digging the dumps, transporting and washing was 1.02 rubles per cubic yard, which according to Purington's recommendation could be cut to 0.55 rubles per cubic yard by storing the dumps at the washing plant and hydraulicing them directly into sluices. This advice was implemented the next year.

Life was relatively pleasant in the Lena Goldfields settlement. Despite being cut off from civilization and transport for nearly eight months a year, the community was well supplied with good food and all essential supplies by careful forward planning. There were large parks, a library, and a primary and secondary school adequate for all the children in the community. My mother was in charge of the higher grades and was largely instrumental in expanding the higher grade school. There were concerts, lectures and amateur theatricals, and a very busy social life among the higher paid employees numbering well over 1,000.

By way of summarizing the Lena Goldfields enterprise, some of the operations were primitive even by 1913 standards, but there were moves made to modernize and reduce the costs which were high in spite of the very low wage level. There must have been much progress made in the next few years in mechanizing and modernizing, because the operation prospered and became increasingly profitable, producing greater amounts of gold. While my recollection as a child is vague, the impression I had from the conversations I heard and the things I saw was that the progress made during my father's tenure as general manager was continuous and rapid.

At the time of Purington's report, Leon A. Ferret was the general manager, having assumed that position about six months before. He was a Russian with previous mining experience and he wrote a very good report, which I have read, to top management on the status of the mines and made many recommendations for modernization and improvement. Two or three years later, Zhurin replaced him as general manager. I remember him as a very handsome man with aristocratic impeccable manners. I would guess that he was not the best of managers, or perhaps he left in anticipation of trouble in Russia, for we saw him in America later. Anyway, my father replaced him within about two years.

One practice that Purington noted as unique in his experience was a technique invented and practiced by the Russians in Siberia to keep water flowing in ditches all winter despite the extreme freezing weather. At the start of winter, the ditch would be progressively sheathed with ice, allowing air space to form under the top ice cover and thus permitting the water to flow all winter.

(Return to interview transcript)

Swent:

How old were you when you moved to Lena Goldfields?

Malozemoff:

I was five years old at the time, and obviously too young to know much about it.

As I said, the first mine my father managed was Prorok-Ilyinski. After a short time there, he proved his skills and was moved to a better mine called Prokopievsky, and then to Feodossievsky, the largest mine in the area. There he did very well, and within another couple of years he was named manager of the richest and considered the best mine of all, Nadezhdinsky.

By 1917 he was freed of the exile of ten years, but that coincided also with the start of the revolution in Russia and the abdication of the Tsar, which took place in April, 1917. As soon as he was freed from the exile, he was named the general manager and managing director of all the mines of Lena Goldfields in Siberia, which was then probably one of the most prestigious positions in mining in Russia. His salary, my mother reports, was 60,000 golden rubles a year, which was a remarkable achievement within about nine years of his exile when the previous family income was probably on the order of 150 or 200 rubles a year!

Swent:

Were you at that time at all aware of the First World War or the Great War, as we call it?

Malozemoff:

Oh yes, because what I have omitted in this account, of course, is the rather interesting way in which mother raised the family. Because of her very close association with her own mother, and also with my father's family who were all in St. Petersburg, she wanted to maintain that contact and continue to be close to both families. Although my father could not travel because of his exile, my mother made a trip back to St. Petersburg about once every two years. And she took us, the children, with her.

Swent:

This was a two-week trip?

Malozemoff:

Yes, about that for the entire trip. She described it in great detail in her memoirs, and I won't go into that, but it was an adventure in itself. She would go to St. Petersburg and we would live with her mother, usually for a period of one or two months, and then go back to

Siberia. It was during one of those trips I remember now that I was about six years old that I became aware that Russia was involved in the Great War, and my awareness of that was the wonder that I experienced in hearing and seeing for the first time an airplane flying over St. Petersburg. I ran out to take a look at the flying machine which was something I had never heard about before. At that time Russia had a few reconnaissance planes of that sort, while Germany had a whole fleet of planes then.

As a child, of course, I was not aware of what was going on at the front. I learned about it later on because I was interested in it. That's a story in itself which has been told many, many times in many books. One of the most impressive accounts of the early part of the war, I think, was Solzhenitsin’s recent book, called August 1914, wherein he describes the first few months of the war and the disadvantages that the Russian Army had compared to the German Army, both in communication and in general strategy, and also in the ability to know where the opposing forces were. The Germans had a fleet of recon naissance planes, whereas Russia had only a very few and they would not venture out often for fear of being shot down. The rigid structure of the Russian Army organization resulted in a situation where the forces at the front could do nothing without explicit orders from headquarters who were way behind the front and really didn't even know the disposition of the opposing forces or even of their own forces. Sometimes they ordered attacks when there were no Germans there. Such an unopposed attack exposed their flanks to German counterattack. At other times they would order an attack against a well-fortified position, and it would be a disaster for the Russians. At any rate, that account is one of the most interesting and dramatic that I've ever read about the First World War on the Russian front.

Swent:

I was wondering, was there much awareness in Siberia?

Malozemoff:

Oh yes. There was definite awareness of what was happening, In the circle of people among whom we lived, some were exiles, some people that came in engineers, doctors, accountants and other professionals, and they were highly educated and very interested in what was going on. They got their newspapers with some tardiness, but on the other hand, we had telegraphic knowledge of what was going on day by day.

Swent:

The Czechs seized the railroad at one point. Wasn't there a group of Czechoslovaks who controlled the railroad?

Malozemoff:

You mean the Trans-Siberian Railroad?

Swent:

Yes.

Malozemoff:

That was after the World War, during the civil war. There's only the one railroad that went all the way out to Vladivostok. Irkutsk was the capital of Siberia. It's located on the western shore of Lake Baikal, perhaps 100 or 120 miles north of the southern tip of the lake, which is a huge lake, the general orientation of which is north-south. In order to avoid the much longer distance of going south of Lake Baikal and then north again in order to continue eastward, in the wintertime they would lay temporary tracks across the frozen lake and take a shortcut across the ice. This was done for years and years.

Swent:

So you were hundreds of miles north of there.

Malozemoff:

That's right.

Swent:

How did all your supplies come in?

Malozemoff:

All supplies came by Trans-Siberian Railroad, were unloaded at Irkutsk, and then taken by horse-drawn wagons to the headwaters of the Lena River. I related this access route earlier when I described Purington's trip to the mines from Irkutsk. It was a long, tortuous route from Irkutsk, but it worked for both freight and passenger traffic.

By the way, during the time we lived in the Lena Goldfields area, I started going to school, to kinder garten. It was organized by my mother; then I went to grade school, which was also organized by her. And I think it was essentially through her influence that my development and curiosity were stimulated to be interested in everything. It was at that time that I became aware that there was such a thing as an encyclopaedia, a book which encompassed all the knowledge that man had ever had. I was fascinated with the idea; I think I must have been about seven or eight years old. I decided that I would begin to learn something about the world by reading the whole encyclopaedia. I never accomplished this task, of course, but I did borrow the first or second volume and read it very assiduously. (laughs)

Swent:

There's nothing wrong with that as a goal!

Malozemoff:

I remember that I became interested in technical subjects during that time. Electricity fascinated me, and I got some notions of what it was all about somewhat imperfect notions. For example, I thought I learned that electric shock is something that's very good for you it burns out any and all disease that you may have. (laughs) Where I got that idea I don't know, but it sounded like a wonderful thing to eliminate your ills and diseases with one electric shock. I suffered some electric shocks, and I thought I'd stay healthy. (laughs)

Swent:

What about electricity?

Malozemoff:

The whole camp was well electrified. There were several automobiles that were used as passenger cars, and the houses, especially the better houses, were well equipped with all the same modern conveniences that you would find in St. Petersburg at that time.

Swent:

And you, as the son of the general manager, must have felt very special.

Malozemoff:

Only for a very short time, because he was made general manager in 1917, and he left there in 1919. So it was only a two-year period. Before that he was superintendent of some of the mines, a lesser position.

Swent:

But still this must have given you quite a feeling of importance and security.

Malozemoff:

Oh yes; however, it was a very democratic place. I know that in school, first kindergarten and then grade school, I was taught like any other child. I had some very good friends at school, I remember, sons of workmen, so that my upbringing was not considered that of a privileged person. The school was for the whole community and was shared by the workmen's children as well as the office workers' children.

My musical education began there too. My father insisted that I should have some beginnings of musical education. I first started on the piano; he was hoping I would go on to the violin, and finally he bought me a small violin. There was a violin teacher in town who gave me lessons my father never had time for that. I remember very well, however, that now and again, maybe once every month or two, he would say, "Well, now you play and I'll see what you have learned." He would criticize my playing severely because he wanted me to play the way he was playing. I remember his particular annoyance was that I couldn't change from going up bow to down bow without interrupting the sound. So he said, "You must work on that, because the most important thing in playing the violin is to have a continuous tone that you can make even when you reverse the direction of the bow." This stayed in my memory as being something to achieve, and, of course, at that time I wasn't able to do so. So I remember him as a very exacting critic, but he really didn't help me very much in my study. (laughs) I don't think the teacher I had was very good, either.

Swent:

It's surprising that there was one there at all, perhaps,

Swent:

We had just been talking about your early education in Siberia. Did you have teachers other than your mother?

Malozemoff:

Oh yes. It was a big enough school and they had several teachers. Actually, I never had my mother as a teacher. She taught, but not in the classes which I attended; she was more in the administrative area.

Swent:

It seems to me you must have felt extraordinarily privileged to go to a school which your mother ran.

Malozemoff:

No, I wasn't conscious of that. I was just going to a school. I never felt special. I think those early years were very happy years. Through the school I met a lot of children that I liked, and we played together. And of course, my brother was only a year and three months younger than I was, and that provided ready companionship.

Swent:

What did you play? What sort of games did little Russian boys play?

Malozemoff:

Very primitive games. There was one game we used to play that involved using pigs' knuckles; one was filled with lead and so was heavier than the others. You threw this against an array of other pigs' knuckles that were set up to see how many you could knock down. It developed your ability to throw, to throw accurately. We played that when we were very young four or five years old.

Swent:

Did it have a name?

Malozemoff:

It had the name Babki.

Swent:

Sort of like nine pins or ten pins?

Malozemoff:

Yes, but we actually threw it actually threw the knuckle ten feet away or something like that. Anyway I became pretty skilled at it. I remember one instance when we finally moved into the general manager's house, a beautiful mansion type of house. We had five servants, and my mother tried to keep the place clean but in Russia you can't keep anything completely clean. Anyway, we had mice. My brother and I shared a beautiful large room with window exposures in two walls. One time when we came in and turned on the lights, we saw a mouse! So I grabbed one of these babkis filled with lead and threw it, and by God, I hit the mouse and killed it! I was so proud of myself! (laughs)

Malozemoff:

Well, those happy days eventually became threatened, of course, by the revolution.

(The following section was written by Mr. Malozemoff after the interview)

My first experience with the revolution was while we were visiting my uncle Paul in Lysva in 1917 in the Ural Mountains, where he was the general manager of the iron and steel works. He was married to my father's sister Lydia. My father's mother my grandmother, was visiting them together with all the other sisters of my father except Natasha. This was between the February revolution of 1917 which led to the provisional government that Kerensky headed, and the October revolution when the Bolshevik communist party finally took control. We were there in the summer of 1917 between these two political events .

It was a very trying time for the grown-ups because they wondered which way Russian politics would go. The provisional government was a moderate government that they hoped would succeed, but it did not appear very stable or energetic. Lenin was trying to manipulate the various factions in order to get a majority and take control, but he didn't immediately succeed.

(Return to interview transcript)

Malozemoff:

In Lysva, a little provincial mining town, there were Bolsheviks who temporarily gained control by force of arms. We stayed in the general manager's mansion, which was always an object of envy for the Bolshevik revolution aries. Quite often, when the soldiers were drunk, they would get together in a little square in front of the mansion and take potshots at the house. I remember this, although my mother does not mention it. The children my brother and I and two cousins, were instructed not to walk around in the hallways where there were windows, but to crawl under the windows so we would not be seen from the outside and be shot at. It seemed to us fun an adventure. It's just one of the things you had to do.

Sometimes the soldiers would shoot anyway. For some reason they liked to shoot at the sloping roof, and the bullets made a hissing noise as they skidded up the roof. However, they never invaded the house, so the family was not endangered. Yet I recall that these very trying times were borne with remarkable resiliency. My mother and my father's family led as gay a life as they could; they had concerts, they had dramatic performances, and my mother participated in all of this. I remember that my father's youngest sister, Sonya, was the only one who was comely all the rest of his sisters were quite ugly, (laughs) When Sonya was made up for a part in the theatrical performance, she looked so beautiful. I remember how I admired her. In spite of the danger and the unsettled times, somehow people in our class, at least, tried to keep their lives more or less normal and tried to enjoy life to the extent that they could.

We stayed there for two or three months, I guess. I became very fond of my two cousins. The boy was about a year and a half older than I; his name was Alexander and we called him Shura. His sister was considerably younger than he was, perhaps about two or three years old. We thought of her as a baby and we were very fond of her; as her older cousin, I used to try to entertain her. We'd play games together. It was a time that I remember as being very pleasurable despite all those outside events that were tragic for many. Mother mentions this, but she doesn't go into the detail that I have gone into about the kind of life we had there.

Malozemoff:

Eventually we went back to Siberia, to Lena Goldfields, and this was when my father became the general manager. We had the most luxurious trip we ever had to the mines. Instead of having horse-drawn carriages, we had a car to take us. And one of the things I remember for some reason but my mother paid no attention to it was that there were hills on the way. We were traveling in Model T Fords that were heavily loaded with baggage. I remember that some of the hills were too steep for the cars, so they turned around and climbed the hills in reverse. (laughs) Later on, in America, I learned that this was a peculiarity of the Model T Fords they had more power in reverse because they were geared lower than in the first forward speed.

Swent:

What were the roads that they were driving on? Were they surfaced at all?

Malozemoff:

Oh no, no, no. They were all dirt roads, just dirt roads. And, of course, during the inclement times they were just mud, deep mud, and difficult to traverse. Actually, I doubt that you could move in cars in the time of inclement weather, either during the melting of the snows or when rains came. That's why the horse-drawn carriage was the usual means of transportation.

In Siberia we were isolated from the worst consequences of the revolution the civil war, the mass executions and the subsequent famine. During the time we were there, we suffered several changes of regime. The struggle, as it has been explained in history books, was between the more moderate revolutionaries that unseated the Tsar and caused him to abdicate, and the Bolsheviks, who were Marxists and more radical. They were the minority party. Eventually they could not get along with each other and their relationship ended in a civil war with armies on each side. The Red army was controlled by the Bolsheviks, and the White army by several of the more moderate opposing parties.

By and large, most of the officers of the Imperial army that fought the Germans joined the White army, although there were some members of the Imperial army that went with the Reds and actually became the officers and leaders of the Red army.

At any rate, in the early part of the revolution there were local regional parties in our mining area that became active. One of the earliest ones was the Bolshevik faction in our mining camp, and they took control of the camp shortly after the October Revolution. We became, all of a sudden, sovietized, and the Bolsheviks were conscious of the fact that much of the population, especially the management, was against them. They were concerned about a possible rebellion against them, and took measures to try to entrench themselves politically and militarily.

One of the first principles they learned in the beginning of the civil war was that the only way to keep control was to make sure that none of the civilian population had any firearms. This was essentially the reason for the post-midnight searches that took place at the most unexpected times. They would search the house for firearms and if they found any, they usually took the people out and imprisoned them. Sometimes they even shot them shot the men it depended on the feelings and the kind of people who executed the raids.

My father was at the mines at that time. Being the general manager, he had the final authority over the workmen. Somehow he managed to establish a working relationship with the controlling Bolsheviks, with whom he was not in sympathy, and to preserve some kind of atmosphere of peace and reduce violence to the minimum. I think my mother records that during that takeover he managed to keep any punitive measures down to practically nothing except in the very beginning when two people were shot and killed during some kind of a confrontation. Those two were the only casualties in that early takeover.

Swent:

I need some information for my understanding: the lands where the gold and minerals were they had belonged to the Crown, had they not?

Malozemoff:

Yes, and the English-controlled Russian company had a lease on the properties.

Swent:

A lease, I see. But your father would have to go to London for higher direction?

Malozemoff:

No, they had headquarters in St. Petersburg.

Swent:

And did they have a board of directors?

Malozemoff:

Oh yes. That's right, Lena Goldfields had a board in St. Petersburg.

Swent:

But then in 1917 what happened to this board?

Malozemoff:

It still continued to exist.

Swent:

And the lease was still honored?

Malozemoff:

Yes. In 1920 it was finally expropriated, but not until then. Father continued as general manager, and continued to be the head of the enterprise. I think he was very astute and diplomatic; he understood the revolutionary movement well enough to deal with the Bolsheviks, and they respected him as well. At any rate, things were more or less under control, although he couldn't control the night searches. We were searched usually after midnight, and my brother and I would be awakened because the armed soldiers would want to see if anything was hidden in the children's rooms under the mattresses or elsewhere. This was an unpleasant time, but due to my father's efforts, they never really abused the people they searched.

Swent:

It must have been very unnerving for the family.

Malozemoff:

For a child, especially, it was very frightening. Then the civil war began in 1918. Kolchak, who was an admiral in the Imperial navy, happened to be in Siberia, and organized armed resistance to the Bolsheviks. There were several forces organized in European Russia, and the White army began to take shape by mobilization. Kolchak was the leader of the movement in Siberia. In terms of population, Siberia was only a small part of the total of Russia, but on the other hand, it was a vast territory to try to control; what he did was to concentrate on certain areas where he knew the Bolsheviks were in control by sending in small military forces to unseat them. Generally speaking, the Bolsheviks in Siberia were small groups of non-military local people who armed themselves in order to take control.

When Kolchak started this movement, he sent a small punitive expedition to Lena Goldfields. My mother describes this event in her memoirs. Because they came with superior forces I don't know how many people they had, but I doubt there were more than 100 or 120 men they easily took over the entire townsite with little or no resistance. The first thing they did was to incarcerate all the Bolsheviks previously in control. When my father made contact with the White army leaders, he learned that the imprisoned Bolsheviks were going to be shot.

Malozemoff:

It took my father considerable effort and some time to dissuade them from doing this, but he tried because he recognized that who knows? six months or a year later the Bolsheviks might be back in power, and if that happened, there would be reprisals. He finally talked the White army officers out of shooting these people. They kept them in prison, but they killed no one.

Swent:

It must have taken a great deal of courage on your father's part.

Malozemoff:

It was really a terribly important step, because later on when Kolchak was defeated, the camp was taken over again by the Bolsheviks, and they knew that the local management and staff were all in favor of the White army takeover. The reprisals might have been horrendous if any Bolsheviks had been shot during that takeover. As it was, when the Reds took control again, they did not engage in reprisals. There were no executions, no one was killed. The second takeover was a more critical one, because the Reds sent more soldiers in order to defeat the well-organized White army punitive expedition.

Swent:

Do you know who the leader of that expedition was?

Malozemoff:

No, in her memoirs my mother names no one whom I can recognize. It might be interesting to mention here an event that I can recollect, although my mother doesn't mention it in her memoirs. When it became evident that Kolchak was being defeated and it was clear that the Bolsheviks would eventually again take over the Lena Goldfields townsite, the local population felt that maybe they should mount some resistance. Consequently, in addition to the small White army contingent, the staff members and the management people mobilized themselves in order to be able to help the White army.

In the course of doing this, there was a man whom our family liked very much by the name of Ozoline, who was the head of the electrical department. I remember him very well. He was very tall, about six foot four, a big powerful man. He was determined that he was going to resist the Bolshevik takeover and was training himself in the use of firearms. He was very fond of me and used to take me out with him to practice throwing hand grenades, He would give me dummy hand grenades , which he had for practice, and we'd go out to a clearing in the woods to throw them as far and as accurately as possible.

Malozemoff:

He told me how to pull the pin to assure an effective explosion. I remember we had several practice sessions which I enjoyed very much. I was about eight years old then.

My mother relates another incident. After the Reds took over she recognized that the first thing they would do would be to search for firearms. My father was gone to America by this time, and we did have a pistol or two in the house and she realized she'd have to hide them. It was during wintertime, and she didn't want to arouse any suspicion by hiding them herself somewhere outside the house, so she asked me to do it. Pretending I was playing outside in the garden, I buried these two pistols in a metal box in the deep snow under a tree. I did this successfully without arousing any suspicion, but of course I knew that when spring came, the box would soon be in evidence. The problem was what to do next.

We had a cook a remarkable person, whom my mother mentions. He was a friend not only of my mother's but also of us children. He loved us. Mother says she doesn't know where he came from, but he was obviously of peasant origin, and an extremely intelligent person. Apparently he read a lot. At any rate, he offered to hide the box with the pistols in it along with some jewels and gold that my mother had.

I recall that we recovered this box from the melting snow one night, and my mother put the jewels in it with the guns. The cook was going to bury it somewhere in the woods. She recounts that she accompanied him, but I remember very well that she didn't because I went with him. It was like a game for me, so interesting. He was drawing a map showing where we went and where we changed direction. Anyway, about a mile away, somewhere close to a creek, we buried the box in the ground. He gave me the map to keep, after making a copy for himself. The interesting thing about this is that when father went back to Russia in 1924, five years later, and got back the concessions which had been expropriated earlier, the cook was still alive. He wrote father, "Don't you want to recover what I have buried? I have the map, and I can recover it for you."

Swent:

And did he?

Malozemoff:

No, he didn't, because my father was too busy; he was in European Russia and the box was buried way out in Siberia. Nothing was done about it.

Swent:

It may still be there.

Malozemoff:

It probably is, and we still have a copy somewhere of that little map we drew together. Those were the out standing remembrances that I have of that period.

It was of course a much more critical period than I realized. During the time of White army successes against the Reds and these successes were quite spectacular Kolchak had a growing army. A lot of people joined, in addition to those originally mobilized. He started with a small army, and by the time he reached European Russia going westward, it was quite a large army. One of the problems I think he had was to supply that army; the larger it got, the more difficult it was to procure guns, ammunition and provisions. Some supplies did come through by way of Vladivostok from the Americans, but that help wasn't sufficient for that size army.

At any rate, his early successes while fighting his way towards European Russia were so spectacular that my father was greatly encouraged that the White forces would prevail and the Bolsheviks would be defeated, and a more moderate regime would be installed in Russia. He felt at that time, reading the political orientation of both the army and its supporters, that the regime would not be purely socialistic but something in between, essentially a democratic regime with a president, and that free enterprise would be honored. He advised the English management of the company that it appeared that a better political climate was in the offing for the investment to modernize the mines and bring in modern machinery and equipment. By this time he could see that the end of the drift mining was approaching. Prospecting indicated that above the rich bedrock gold streak, the gravels were still gold-bearing but of a lower grade. A bucket line dredge could be used to recover the gold, and he recommended this change. Mining would be on the surface. The dredges are great big machines: the digging part is a continuous bucket line that collects the gravel, while the dredge floats in an artificial moving pond. As it digs, the pond advances with the dredge. The gravel thus excavated is dumped into a hopper and then into a trommel screen with water jets to disintegrate the gravel; the screened product then flows over riffles which are charged with mercury, resulting in concentration and amalgamation of the gold. The gold- free tailings come out on a conveyor at the other end of the dredge and are dumped in the same pond. The dredge keeps on advancing, digging ahead and getting rid of the waste in the back. Dredges have been successfully used for gold as well as tin recovery for many years, long before 1917.

Swent:

They were actually developed here in California, weren't they?

Malozemoff:

Yes, I believe they were developed in California, and used in Australia and in the tin areas in Malaya. At any rate, the great advantage of dredges was that excavation was done very cheaply, and the total operating cost of these large machines was only three to five cents per cubic yard of gravel. Therefore low grade gravels could be profitably mined. Gravel that would run ten or twelve cents a cubic yard could be very profitable. The Lena Goldfields deposits were considered to be richer than that, hence my father envisioned a very profitable enterprise.

The London management agreed to his recommendation. He was authorized to come to America to order a dredge and other special equipment. He had to beef up the power plant, for example, because the dredge was electrified and required much more power than was needed in the drift mines.

Swent:

One more interruption: what was the source of power?

Malozemoff:

Thermal plants burning wood.

Swent:

Local wood?

Malozemoff:

Yes. Well, after he came to the United States, he spent some time drawing up specifications, bargaining, and preparing orders in Milwaukee.

Swent:

What company would he have been talking with?

Malozemoff: