Oral-History:G. Frank Joklik

About Gunther Franz (Frank) Joklik

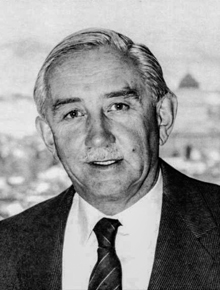

G. Frank Joklik is President and Chief Executive Officer of Kennecott Corporation. Born in Vienna, he grew up in Australia. He received a B.Sc. with First Class Honors and a Ph.D. in Geology from the University of Sydney. He came to the U.S. in 1953 as a Fulbright Scholar at Columbia University. Mr. Joklik began his career with Kennecott in 1953 as an exploration geologist. and headed up minerals projects in Canada and the U.S., based first in Quebec and then at Kennecott's headquarters in New York City.

After ten years Mr. Joklik joined AMAX. Inc. and returned to Australia to manage the development of the Mt. Newman iron ore deposits and other projects. He was subsequently elected a Corporate Vice President. He rejoined Kennecott in 1974 and became President in 1980. In June 1989, RTZ Corp. PLC purchased the company and Mr. Joklik continued as President and Chief Executive Officer.

Mr. Joklik is a member of the National Academy of Engineering, a Director of First Security Corporation, and a member of the Board of the American Mining Congress. He is active in the leadership of other industry, civic and charitable organizations.

Further Reading

Access additional oral histories from members and award recipients of the AIME Member Societies here: AIME Oral Histories

About the Interview

G. Frank Joklik: An Interview conducted by Eleanor Swent in 1993 and 1994, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1997.

Copyright Statement

All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and G. Frank Joklik dated March 15, 1994. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley.

Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the Regional Oral History Office, 486 Library, University of California, Berkeley 94720, and should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user. The legal agreement with G. Frank Joklik requires that he be notified of the request and allowed thirty days in which to respond.

It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows:

G. Frank Joklik, "Exploration Geologist, Developer of Mt. Newman Mine, President and CEO of Kennecott, 1949-1996; Chairman, 2002 Olympic Winter Games Committee," an oral history conducted in 1993 and 1994 by Eleanor Swent, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1997.

Interview

INTERVIEWEE: G. Frank Joklik

INTERVIEWER: Eleanor Swent

DATE: 1993 and 1994

PLACE: Berkeley, California

Family and Early Schooling, 1928-1944

[Interview 1: October 18, 1993)

Swent:

This is Eleanor Swent interviewing [Gunther Franz] Frank Joklik on October 18, 1993. Here we are in Salt Lake City, Utah, on a beautiful October day, but we have to go back to your beginnings which were in 1928 in Vienna. Do you want to start the story there?

Joklik:

Yes. Here in Salt Lake I've tended to be identified with Kennecott and the 2002 Olympic Winter Games. But the trail goes back and begins in Vienna on May 30, 1928. The first decade of my life was in Vienna and I have nothing but pleasant recollections of those years. My parents, of whom I was very fond, spent most of their lives in Vienna. I should talk a little about who they were and where they came from.

Swent:

What was your father's name?

Joklik:

His name was Karl Friedrich Joklik. At the time of my birth he was employed in Vienna by a division of Siemens as an electrical engineer.

Swent:

Siemens is not an Austrian company, is it?

Joklik:

No. It's a German company which had an Austrian affiliate called Siemens-Schuckert. My father was born in a town about sixty kilometers from Vienna called Pressburg, now better known as Bratislava, capital of the recently formed Slovac Republic.

Swent:

That's only sixty kilometers from Vienna?

Joklik:

That's about all, yes.

Swent:

I didn't realize that.

Joklik:

He was brought up in a naval academy and his father, my grandfather, was an army officer. You may recall that Vienna, at the time my father was born, was the capital of the Austro Hungarian empire which had an extensive shoreline on the Mediterranean Sea. Hence, there really was an Austrian navy. He was brought up fairly strictly until he graduated, not long before the First World War.

He was born in 1893, so at the outbreak of the war he was twenty-one. As a junior naval officer, he served on a light cruiser named the “Helgoland.” Later, he commanded a submarine. After the war, the Austrian navy ceased to exist because Austria became a land-locked nation. He decided to go back to school and enrolled at the Technical University in Vienna. He graduated in electrical engineering. Upon his graduation he joined Siemens.

Joklik:

My mother was born in a relatively small town called Mahrisch Trtibau. This now has one of those difficult Czech names, Moraska Trbova. Her maiden name, Giessl, was that of a German speaking family of land owners which had lived in that area for hundreds of years. But her father did not follow the farming tradition. He pursued an academic career and became headmaster of the local high school. That was his position when my mother was born in Mahrisch Trtibau in 1896.

Swent:

And what was her name?

Joklik:

Helene. My mother's full name was Helene Louise Adele Giessl. She went to high school in Brunn, which is now called Brno and is the second-largest city in the current Czech republic. Then she went on to Vienna to attend the teachers' academy. That's where she met my father when he embarked on his engineering career. They were married in Vienna on July 11, 1925, in the Stefansdom, or St. Stephen's Cathedral.

My parents were a striking couple. Both were tall; my father fair, blue-eyed and handsome, and my mother dark-haired and beautiful. They were principled. Their word could be relied on. My father's military background provided him with a disciplined approach to life, yet the ability to appreciate and be the life of a good party. My mother was highly cultured in the arts and music. She was spirited and certainly had a mind of her own. Both were loving, and let us know they were proud of us.

To go on, then, in 1937 my father left Siemens to join an Austrian steel company, the English translation of which would be Styrian Steel Works; in German: Steyrische Guss-Stahl Werke. He then entered into a contract with the company to go to Australia and establish sales offices in Sydney and Melbourne.

Swent:

Let me just quickly--you said that you have a brother.

Joklik:

Yes. My brother is a year and a half older than me.

Swent:

I see. So he was also born in Vienna.

Joklik:

Exactly. He and I were and are close.

Swent:

Would you like to give his name?

Joklik:

Yes. His first name is Wolfgang, just like Mozart. Wolfgang Karl. He is a renowned person. He recently retired from the position of chairman of the Microbiology Department at Duke University. He has received many high academic honors, including membership in the National Academy of Science. He is one of the two or three leading virologists in this country. At his retirement dinner there were several Nobel Prize winners who came from various parts of the world to honor him.

Swent:

Quite a distinguished family.

Joklik:

Well, thank you. Both of my parents were bright, and my brother is, too. I think I'm the black sheep of the family.

Swent:

Oh, I don't think so. [chuckling]

Joklik:

Anyway, at the time of my birth my parents lived right in the city of Vienna, in a large apartment which I remember fondly. There was a live-in maid with whom my brother and I had a--put it this way, a relationship of respect when respect was due. Anyway, it worked.

We went to a public primary school. Teaching was of a high standard, and discipline was strict. There was strong emphasis on academic performance and no one, neither the students nor the parents, questioned that. My brother was a year ahead of me. We both were generally at the top of our respective classes.

Swent:

I would guess you didn't have much choice in that.

Joklik:

In what?

Swent:

Your parents probably expected you to be at the top, didn't they?

Joklik:

Well, but there was choice. Sure, academic performance was expected, but not only of us. It was expected of all of us in school. It was not considered a negative to perform well academically. This doesn’t mean that the kids were always at their books, or that they were terribly serious. I think I was in a class of twenty-five. Many were my close friends. We used to play sports, particularly soccer and gymnastics.

Swent:

It was a boys' school?

Joklik:

Oh, yes! [laughter)

Swent:

That's all we need to say about that.

Joklik:

I don't think there were any co-ed schools in those days.

Swent:

Was it a basic classical curriculum?

Joklik:

Yes. When we left for Australia, I had completed four years of school. No languages at that stage, but our parents gave us private lessons in English from the second or third grade.

Swent:

Was this a common thing?

Joklik:

I know that some of my friends also had English instruction. Our parents recognized that English was an important language, world-wide; and so we had English lessons, even before my father's appointment to the Styrian Steel Company.

Swent:

Did he also know English?

Joklik:

Some. But he wasn't fluent.

Swent:

And your mother?

Joklik:

She spoke very good French and some English. Anyway, the environment in Vienna, as I recall it, was one of security, direction and parental care.

Swent:

I thought music. One immediately thinks of music in Vienna.

Joklik:

I started piano lessons at age seven or eight. Now, I quickly found that I didn't have much talent. Lessons continued until the age of revolt, at thirteen or fourteen years old, when I could plead pressure of other activities. I think my brother did better than I did. I love music, but manual dexterity on the keyboard wasn't my attribute.

As I think I've already said, we attended a boys' school- boys in the classroom, and almost all boys in extra-curricular activities. My knowledge of the world of girls was a closed book to me until--well, for quite some time--because in Australia we also went to a boys' school.

Swent:

What kind of clothes did you wear to school?

Joklik:

There wasn't a school uniform, but--I 'm trying to think. I was still in short pants, of course, and a shirt and jacket or sweater.

Swent:

A tie, I suppose?

Joklik:

Ties? In the wintertime. I don't think in the summertime.

Swent:

Cap?

Joklik:

No. Oh, in the winter, when it got cold.

Memories of those days include the supportive environment in the school where one's form master, although strict, insured that students didn't fall through a safety net. One evening, I was asked to recite a poem. My brother had developed flu and, even though he was a year ahead of me, I was asked by his form master whether I would substitute for him. I said yes and learned the poem, but getting up on the stage in front of an audience of maybe a hundred or two hundred fond parents was something I wasn't comfortable with. Fortunately, I didn't have a memory lapse. Afterwards my parents asked me why I started grinning halfway through. The reason was that this form master of my brother 's was sitting in the front row with a broad grin on his face, directing my recitation with his hands, as if he were conducting a choir.

In the evenings we'd do our homework. In the drawing room, to which my parents retired after dinner, my mother would play. She was an excellent pianist. And my father would be reading. There was always a box of chocolates on the drawing room table. Occasionally, my brother and I would be invited to partake. But going to sleep by the sound of my mother playing the piano is something I haven't forgotten.

Swent:

It sounds like a delightful memory.

Joklik:

Yes. On weekends, apart from organized school activities, we'd go on excursions. We'd go a little distance outside the city by car or train, and then hike on well-marked trails through the forests and meadows. I'm amazed at the distances we, as little kids, used to cover with our parents. Sometimes we'd carry a pack sack, stay overnight at an inn and then return to the train station or wherever we'd started from.

Swent:

How far were you walking? Ten miles?

Joklik:

Well, eighteen kilometers would not be unusual in a day.

Swent:

That's a lot for little boys.

Joklik:

Yes. It wasn't necessarily always done with the greatest enthusiasm [laughter], but it taught us to develop a little stamina and appreciate the beauties of Mother Nature.

We should also talk about summer vacations. They were usually taken in the mountains or by some lake. We would go for, say, six weeks and my father would come for a couple of weeks, and then on weekends, from Vienna. Towards the end of summer, we'd go to Mahrisch Trtibau and spend time on the Giessl family farm. At that time, it was owned by my mother's aunt Emilie and run by her husband, a retired army colonel whom we called Uncle Hans. He was a bear of a man, a wonderful person with a great sense of humor.

My brother and I would help with plowing or loading hay; or just go in the forest and gather mushrooms. Every summer we would spend a couple of weeks there.

Swent:

It sounds delightful.

Joklik:

Let me leap ahead half a century to relate that in the fall of 1993, Pam and I happened to be in Europe in connection with Salt Lake City's bid for the 2002 Olympic Winter Games. After the meetings, we spent a few days in Prague. On the spur of the moment, we rented a car and drove the 200-odd kilometers east from Prague to visit Mahrisch Triibau.

Swent:

Had you been back in the meantime?

Joklik:

No. It was behind the Iron Curtain. Frankly, I thought the town hadn't changed that much. Before the war, one-third of the population of Czechoslovakia was German speaking. They all were expelled after the war, three and a half million of them, my great uncle and aunt included. They died shortly afterwards. I did find the old family cemetery, but the old headstones had been plowed over to make place for new graves. It's still a beautiful site, with a 17th century church within the cemetery grounds; but the church had been closed up for decades and was in a sad state of neglect.

Swent:

Were the houses there that you had been in?

Joklik:

Yes, in the town of Mahrisch Triibau, but not where the farm used to be. During collectivization of farms under the Communists, essentially all farmhouses and most churches were destroyed. Farmers now live in three-and four-story concrete buildings the Communists were fond of erecting.

Swent:

It must have been a wonderful visit.

Joklik:

Pam has a great sense of direction, which came in handy because there are no road signs in English or German. We didn't know one word of Czech.

Swent:

You didn't find any relatives.

Joklik:

No. As I said, all German-speaking people were expelled after World War II. But in the cemetery there was an elderly Czech gentleman. I communicated with him through sign language. By then, it was close to six o'clock, and I knew it would get dark in another hour. As I was leaving the cemetery, the old man stopped me and pulled car keys from his pocket. He motioned towards a little car parked just outside the cemetery gate. As near as I could gather, he wanted to tell me, "Look, let's go to the registry office and check whether we can find a record of your relatives." I thanked him very much and wished we'd had the time to go, but we had to start driving back to Prague.

Swent:

You mentioned the church. Were your family Roman Catholic?

Joklik:

Yes. Austria was and is predominantly Catholic.

Swent:

So then your father left Siemens and went with this Styrian company.

Joklik:

With Styrian Steel Works, yes, Steyrische Guss-Stahl Werke, to open offices in Australia.

Swent:

Oh, he opened offices there.

Joklik:

Yes. He signed a contract on the 2nd of December, 1937. The events leading up to our departure included many parties with our relatives, of course all on the assumption that we'd be back in three years. But we were going right around the world. There weren't any commercial airlines in those days, which meant a long sea voyage. We said our fond farewells, which I still remember clearly. The packers had come several days before. What we took with us on the ship consisted of two of those big--

Swent:

Steamer trunks? [quietly]

Joklik:

Steamer trunks. You opened them up and could live out of them. Two of those and countless suitcases. Eight large crates were shipped separately, including the baby grand piano.

Swent:

Did you have any pets? Were there animals?

Joklik:

No. Fortunately, because Australia had some of the toughest quarantine laws in the world. Quarantine periods were six months and longer.

On the 6th of January, 1938, we took the train from the South Railway Station, the Stid Bahnhof, in Vienna. The route was Venice, Rome, and Naples, where my brother and I had our first sight of the sea. That was a thrill in itself. One of my--

Swent:

You didn't see it at Venice?

Joklik:

No. It was night-time. Well, that's not quite true. We were awake and saw a reflection of moonlight on the water, but it wasn't 'til the following day that we saw the open sea.

Swent:

Really saw it.

Joklik:

We checked into the hotel in Naples and spent a day visiting Pompeii. I could swear Vesuvius was emitting smoke at that time. And then on the 9th of January, 3:00 p.m., the P&O Liner--have you heard of the P&O Line?

Swent:

Certainly have.

Joklik:

Yes. The P&O Liner, "Orion".

Swent:

That's where the term "posh" came from, I think.

Joklik:

I don't know. Really?

Swent:

I think so. P&O, I've forgotten what the "sh" stands for, but--

Joklik:

P&O stood for Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company.

Swent:

But, if you went out in a certain accommodation it was called p-o s-h I think: "Port Outbound Starboard Home"!

Joklik:

We cast off at 3:00 o'clock that day and within an hour, my mother, my brother and I were seasick!

Swent:

Oh-oh! [mutual laughter) You don't remember it with too much pleasure, obviously.

Joklik:

Look, everybody gets seasick when they first get on a boat. I think in twenty-four hours my nausea was over.

Swent:

Oh, it didn't last the whole trip, then.

Joklik:

Just a matter of finding your sea legs. The weather was pretty bad when we set sail. It lasted for a day or so and then cleared up.

Swent:

You went through the Suez Canal?

Joklik:

Yes. Port Said was the first stop. At each stop there was a tour of the city. Those were the days when a passenger liner berthing was a relatively big occasion for the local people.

Swent:

It must have been terribly exciting for a little boy.

Joklik:

It was. Next stop was Aden, then Colombo.

Swent:

A lot of water between Aden and Colombo.

Joklik:

Yes. Six days' travel.

Swent:

Pleasant weather at that time of year.

Joklik:

It was. Although, when you get close to the Equator it doesn't matter what time of the year it is. In Colombo, I remember a guide walking up to a tree, cutting a notch in it, and letting the sap ooze out. Before you knew it, he had a big rubber band in his hand.

After Colombo, the next stop was Fremantle, after a week's straight sailing. Life on board was pleasant. They had a children 's playroom where we spent much of the day. There were organized games and swimming and fancy dress parties. We'd go there whilst our parents were up on deck for dinner and dancing.

Swent:

I've forgotten. Fremantle has just one "e", Fre--

Joklik:

F-r-e-m-a-n-t-l-e, the port for the city of Perth. One of my first comments about Perth was that it didn't differ much from a European city. We didn't know what to expect in Australia. We'd read books, of course. In retrospect, Australia was easy to get adjusted to.

In Adelaide and Melbourne we didn't go on shore. There were measles epidemics in both places, so no kids were allowed off the ship.

Then Burnie, which is on the north shore of Tasmania. It's still a sleepy town today. We berthed early; dawn was just breaking, and I saw stevedores handling bales of wool with their hooks. They were dressed in long pants, grey singlets and broad brimmed hats that I first thought were cowboy hats. That was my first impression of "Aussies" at work.

Swent:

I've been to Perth and Adelaide and Melbourne, but I've never been to Tasmania at all.

Joklik:

A very beautiful island. But cold and windy in the winter. The "roaring forties" come through there.

Swent:

I've a feeling that's quite a voyage from Perth around through there, isn't it?

Joklik:

Yes. From Burnie we sailed back towards the mainland, across the Bass Strait, where all the oil has been found. And then north to Sydney.

Swent:

And by now you're at the end of January.

Joklik:

Yes. In fact, into February by now. In Sydney and Melbourne a normal summer might have two or three hot spells of a few days. A record heat wave occurred in January, 1939, when the thermometer hit 107 degrees F and the mid-day sun was obscured by the smoke from bush fires ringing the city. But normally, the summer weather isn't oppressive.

Joklik:

We arrived in Sydney on the 10th of February, 1938. We booked in at the Wentworth Hotel, which was the best at that time. I remarked on my first impression of Sydney--funny for one who'd never been to America-- said it was totally Americanized. [mutual laughter] And I referred to the city as "a mass of skyscrapers." The tallest building was the Shell Oil building which must have been eleven or twelve stories high. I'd never seen a building that tall, but to me that was a skyscraper. Then there was the AWA building. It had a radio tower which was the highest feature of the city. Those buildings are dwarfed by the skyline of Sydney today.

The next day we started to look at schools. We first visited Scots College which made a so-so impression on us. We went on to Cranbrook which we immediately liked. Our schooling at Cranbrook became a big part of our formative years. First we had to order school uniforms which were grey suits, blue shirts, grey knee-length socks--we both still wore shorts at that time--black shoes and either school hats, boaters or visor caps.

We started at Cranbrook barely after the beginning of the school year; let's see, the 10th of February is usually the beginning of the school year. The kids stared at us as we went to school, because to their eyes we were dressed a bit funny. It took a couple of days to get our school uniforms together. And our knowledge of English still left much to be desired. We had learned a lot on the ship. What was it, five weeks or six weeks on the ship? We embarked--

Swent:

January 6th to February 10th? Five whole weeks. At that age you can learn a lot of language in that time.

Joklik:

Oh, sure. Especially, since we made some good friends on the ship. Apart from the kids, I remember a Mr. Talbot Wilson from the Jersey Islands. He took a shine to our family. We corresponded with him afterwards. He wrote down our birthdays and used to send us birthday presents. He was an optimist. As late as a month before the war, he wrote to us that he was convinced there would be no war, simply because he believed the people would not follow the "politicians."

After only a few weeks, we were already beginning to feel at home at school. Cranbrook was and still is a boys' college, a member of what was called the Associated Schools in Sydney. The term "college" is here used in the English sense of a private high school. There was intense rivalry between the Associated Schools and another group of private schools, ironically called the Great Public Schools.

Cranbrook was founded in 1918 and is in the beautiful grounds and buildings of the former residence of the governor general of New South Wales. It's a Church of England school, which didn't really affect my brother and me, or the other few kids who were Catholic. We attended religion classes given by the school chaplain. Services were not frequent and we were free to attend or not. We took catechism classes from a priest at a nearby Catholic school to prepare for confirmation. That involved an oral examination, administered by the Archbishop, later, Cardinal Gilroy. He asked me to recite the Apostles' Creed which hadn't learned in English. So I rattled it off in German. When I finished, he smiled benignly and said, "I didn't understand a word you said, but your fluency convinces me that you know it just fine."

When my brother and I started at Cranbrook, in 1938, the student body numbered about 400. The headmaster was General Ivan Mackay who later, in the Second World War, became Lieutenant General Sir Iven Mackay, so-called "Hero of Tobruk;" an outstanding military man, a scholar and a gentleman. He took a shine to my parents and, I think, a little to us boys. We felt comfortable with him, though he had an imposing presence.

My father opened his offices in Sydney and Melbourne. I remember the afternoon my brother and I were walking past the school oval down to the playing fields, and a car pulled in behind us. We looked around and it was my father in a brand new Chevrolet. I don't think I'd ever really taken a good look at an American car before. That's mostly what there was in Australia at that time. There weren't any cars made in Australia; there were a number of small imported English cars: Morris, Vauxhall, and so on, but the vast majority were Chevrolets and Dodges and Buicks and Oldsmobiles; you know, the standard GM, Ford, and Chrysler products as well as some that don't exist any more, like Packards, DeSotos, and Studebakers.

Before I change the subject, I should say that when my father bought the Chevrolet, my mother hadn't done any driving. She started taking lessons, which my brother and I became aware of, but my father didn't know. Then one evening, before dinner, she slipped her brand new driving license under his plate. He was flabbergasted. We celebrated and my father admitted he'd noticed that my mother 's shoes had become inexplicably buckled, presumably by my mother's, at times, frantic recourse to the brake pedal.

Swent:

Now, was your father overseeing manufacturing?

Joklik:

No, sales. His company made specialty alloy steels. I wasn't too familiar with the technology, but they must have been tungsten, molybdenum, nickel and chromium alloys. Austria was at the cutting edge of this technology. It was a matter of testing the market here and there and establishing a distribution network.

We looked around for a house to rent and found one in a pleasant suburb. There were palm trees in the garden. We'd never seen palm trees close up, except on the journey out. The idea of having to water the lawn every day and then cut it, once or twice a week, was also new and exciting to us.

Our first acquaintance with the Australian bush was seeing these strange trees which are not deciduous--the eucalyptus trees and the fauna that inhabited them. There were parrots and budgerigars. Near the city you didn't see kangaroos, but there were parks near Sydney where kangaroos were kept. We used to go out and feed them and the koala bears.

On some of our trips we'd see snakes. We were well aware of Australia's many species of snakes, most of them venomous. Occasionally we'd run over one with the car, and stop to take a close look which wasn't, perhaps, the smartest thing to do.

Our fellow students were bright and pleasant. I won't say we didn't get into fights, but by and large we quickly formed friendships and began to spend time with them outside of school hours. Of course, in those days there wasn't any television. Either we'd kick a football around or we'd go down to the beach and rocks around Sydney Harbor, collecting shells and oysters.

Swent:

I've seen it; been there. Beautiful.

Joklik:

I think it's the most beautiful harbor in the world.

Swent:

I think it's generally called that.

Joklik:

Vaucluse is the suburb I grew up in. We were only a hundred yards or so from the water. Of course, you couldn't just jump in and swim because of sharks. A summer didn't pass without one or two or three people getting taken by sharks.

Swimming in the harbor was done from beaches that had shark nets around them. If you wanted to swim, you went in the harbor; if you wanted to surf, you went to the ocean beaches. When I was older, I'd dive and look at the holes in the shark nets. They were yards across, and any sharks that wanted to could come in and help themselves. [mutual laughter]

Swent:

You didn't know that as a boy, though.

Joklik:

No, we didn’t know that.

Swent:

Oh, my. It sounds like a wonderful childhood, though. Really.

Joklik:

In the wintertime, it used to get dark around five-thirty or six o'clock. On a sports day, as they mostly were, we didn't get home much before dark, and then came dinner and homework. In the summer you'd swim practically every day, starting from late October until early April.

Meanwhile, learning progressed rapidly; I don't mean just academically. Impressions of many kinds engulfed us. People were kind, not only the kids at school. My parents developed friendships with other parents who came to the house for dinner, and we'd visit them.

Whenever there was a birthday at school, the boy concerned would give a party. There were several kinds of parties. One was to meet at one of the wharves close by, get on a chartered boat-an average of forty or sixty kids--and go out to one of the islands in the harbor. There would always be huge quantities of ice cream, packed in dry ice. And tons of food. You'd hell around all day. The party on the island was often combined with a movie that night.

Swent:

Who were the adults in attendance?

Joklik:

The parents of the kid giving the party.

Swent:

This was on a weekend, so it wasn't a school day?

Joklik:

On weekends. Right. There were beautiful parks in Vaucluse. We would meet there for parties. Sometimes they'd have horses. Many of the kids at school, especially the boarders could ride bareback at age ten or eleven.

Swent:

They probably came from the Outback where riding was common.

Joklik:

Yes. They came from families that had sheep or cattle stations.

Swent:

So you were in, what, the equivalent of the fifth grade?

Joklik:

I'd had four years of school in Vienna. I went into fifth form at Cranbrook, but within a year both my brother and I had skipped two grades. That was the good news. Of course, when I eventually graduated from Cranbrook and went to the university, I was only sixteen. I was always amongst the youngest, which taught me self defense.

Swent:

So Cranbrook went all the way through high school, then; secondary school.

Joklik:

Yes, but I should back track a little. From early 1938 through September '39 was a sort of golden period. At the same time, we were aware of the clouds of war gathering. My father was the eternal optimist, convinced there would not be a war. His standard speech was, "Believe you me, I've been through a war, and no one in their right senses would go through another one."

Many of our friends in Sydney were the same way. We had a family doctor, Dr. Hobbs. I remember going to his clinic one evening with my father. We sat there chatting. Dr. Hobbs had also been in the First World War and he, like my father, said, it's just impossible there could be another war, because people wouldn't want to endure the suffering.

My brother and I were concerned because there was talk at school about war. My mother, who was more of a realist than my father, worried.

Swent:

What was your citizenship?

Joklik:

Austrian. Then came the occupation of Austria by Germany, in November 1938--

Swent:

November, '38. Okay. Is that what they call the Anschluss?

Joklik:

Yes. It set the stage for what was to come. The Germans annexed Sudetenland, which was the German-speaking part of Czechoslovakia; and then they occupied the rest of Czechoslovakia.

Swent:

And you were aware of this. In school as well as at home?

Joklik:

It was all over the papers.

Swent:

How did the papers get their news?

Joklik:

Transoceanic cable. Cables were laid before the First World War.

Swent:

No thought of Japan at that point, was there?

Joklik:

No. Without TV, you actually read newspapers and books. When you had visitors to the house, you talked. You didn't sit together and watch TV.

Swent:

Very different era, wasn’t it?

Joklik:

Yes.

Swent:

Did your mother have household help in Australia?

Joklik:

Yes. But not live-in like we had in Vienna. She had a woman come twice a week, as I remember.

Swent:

It must have been a tremendous adjustment for her. An entirely different kind of life.

Joklik:

Yes. I'll have more to say about her.

Let me make a couple of more comments about the ambience of Sydney in those days. Public transportation by way of trams and buses was good because not all that many people had cars. My father used to drop us at school in the mornings, but we'd take the tram or a bus home. Home deliveries were standard. The baker, the grocer, the greengrocer, the milkman--all of these, as a matter of course, made deliveries to the house. There weren't any washers or dryers.

Joklik:

Laundry day coincided with visits by the cleaning lady, and my mother and she would go at it.

Other characteristics of the time: dentists, for example. This was before the days of fluoride. Cavities were filled without numbing. All a dentist said was, "Open wide, please".

Swent:

Those were not such good days.

Joklik:

[chuckling] No. But, you were used to it.

There seemed to be a lot more in the way of flu, measles and childhood diseases. We went through them all. I forget what inoculations were for, but they weren't effective against a wide range of illnesses.

Swent:

Smallpox is about the only one, wasn't it?

Joklik:

Smallpox, yes, everybody had those marks on their arms.

Swent:

That was about it, I think.

Joklik:

I remember I had adenoids removed before we left Vienna. I had a general anesthetic, but hated the smell of ether. And then I had my tonsils out in Sydney.

Swent:

So the tonsils and adenoids were done separately.

Joklik:

Adenoids were done first. But then I got a run of colds and the family doctor said to have my tonsils out. It seemed that everybody had their tonsils out.

Joklik:

This leads us up to the outbreak of war, when everything changed overnight.

Swent:

And what was the date that you considered; that was when England entered the war? Was it 1940? I guess, Dunkirk?

Joklik:

Well, yes. Germany declared war on Poland on the 1st of September, '39, and Britain declared war on Germany on the 3rd, two days later.

Swent:

'39.

Joklik:

And then came some difficult times. At four-thirty in the morning of the 4th, there was a knock on the door and two detectives arrested my father because of his Austrian nationality. He was released a month later, in October.

Swent:

Where was he held during that month?

Joklik:

At an internment camp some distance from Sydney. He was released in October, but in June of 1940, when the Germans invaded France via Belgium and Holland, he was re-interned and transferred to a camp in Victoria. He wasn't released until the end of the war. In those five years he aged twenty.

Swent:

I presume he had no employment, of course.

Joklik:

No. There was no more income. The assets of his firm were liquidated through quick sales, and a determination was made by a government agency as to how much of the proceeds was going to be used for sustenance of the family. Everybody in Australia was still assuming the war was going to be short. An allowance of eight pounds a week was determined. The car was confiscated, and my father's office was closed. Everything changed from secure to insecure.

Swent:

You were allowed to continue at school?

Joklik:

Yes. Although there was constant worry whether my mother could continue to afford the school fees. We moved a couple of times to successively more modest accommodations. Frugality became a way of life. My brother and I, though instinctively competitive, stuck together in tough situations. We were conscious of the need not to increase pressures on our mother. The weekly allowance of eight pounds was reduced to six pounds after a year or two and eventually discontinued. But before then, mother had gone out doing domestic work. You can imagine what harsh, physical work took out of her, an educated, thoroughly cultured lady. But she had pride and bore her lot with great dignity. Even then, she would find time to help us with our French or critique our English compositions--not perhaps the vocabulary, but certainly the logic and style of writing.

To keep us at Cranbrook, she arranged with the headmaster and the school council that our fees be reduced by half, with the understanding that the other half would be repaid at war's end. This was a wonderful gesture on the part of the school, prompted by their desire to keep my brother and me as students. We had already reached the top of our classes academically and were showing promise in sports. Perhaps the school anticipated a future dividend from our performance.

My mother repaid the arrears in school fees from her earnings as soon as she could after the war ended. A few years ago, my brother and I endowed the Helene Joklik scholarship at the school in her honor.

As my brother and I continued school at Cranbrook, we gradually made the transition from simply adapting, to contributing and, in some respects, leading--both in and out of the classroom.

Joklik:

When General Ivan Mackay went back to active army duty in 1940, a former headmaster, Reverend F. T. Perkins came in as acting headmaster. He was a respected classical scholar and former track-and-field star--a kindly man with a strong sense of fairness and an exacting teacher. He stayed on when Brian Hone later took over as headmaster and was my Latin teacher until matriculation.

A word of explanation about the education system, as it then functioned. The state of New South Wales had two standard public examinations which were administered at all schools, private and public--one at the end of Grade 10, for the Intermediate Certificate, and the other at the end of Grade 12, for the Leaving, or Matriculation Certificate. Results were graded as A, B, C or failure. Up to eight subjects could be taken for the Intermediate examination, and six for the Leaving. Two of the subjects for the Leaving could be taken at an advanced level called Honours, First class or Second Class. The best achievable examination results, therefore, were eight A's in the Intermediate and two First Class Honors and four A's in the Leaving. It would be false modesty not to mention that my brother and I achieved both.

Back, now, to Reverend F. T. Perkins. Under his guidance, Latin became my favorite subject. To him, the construction of a Latin sentence was the ultimate intellectual exercise, resulting in total satisfaction. Simply put, I got hooked. We worked hard at Caesar, Cicero, Livy, Horace and Virgil and enjoyed it. I also became enthusiastic about Roman history and culture. Needless to say, Latin also benefited my English composition.

I should have mentioned that almost all the masters [teachers] at Cranbrook had nicknames which they earned through some idiosyncrasy or distinctive mannerism. Reverend Perkins' nickname was "Polly," from so far back that I never discovered the origin.

Apart from grades in every subject each fortnight, we received class rankings and written masters 'reports at the end of each term. Two of his report cards, when I was in eleventh grade at age fifteen read: "He is an example of a healthy mind in a healthy body" and: "He is daily qualifying himself for future command." Praise received, at the time, from one not given to superlatives.

For purposes of physical training, drills, intramural sports and other out-of-class activities we were divided into houses, each named after a former governor of New South Wales. My brother and I were in Strickland House, and "Polly" Perkins was our housemaster. He wasn't coaching track and field any more, but occasionally he would volunteer advice if he thought it worthwhile. On this particular afternoon, we were before the last event of an inter-house track meet, a 4-x-100-yard relay. I was to run the anchor leg, although sprints were not my specialty. Among others, I was up against Philip Dean who was the age sixteen-and-under sprint champion. The general view was that unless I started with a seven- or eight-yard start, we would lose. Well, our third runner, a close friend with whom I had intensively practiced, gave me a perfect hand-off and a five-yard start over Dean. For once, I hit my stride almost immediately and pounded the track as never before. At the finish, I was still five yards ahead."Polly" sauntered over, clearly tickled pink. He beamed at me over his gold-rimmed half glasses and just said: "I thought you could have got up on your toes a little sooner." You had to know him to appreciate that his thinking it worthwhile to dispense advice was more flattering than effusive congratulations would have been.

Joklik:

In late 1940, or early 1941, a much younger man, Brian Hone, took over from Reverend Perkins, who had been the acting headmaster. Hone was later knighted and became recognized as one of the leading educators of Australia. He was originally from Adelaide, I believe. When he came to Cranbrook, he had spent some years as headmaster of a private school in England. Having been a Rhodes Scholar, he was also an outstanding athlete. I remember his first appearance at the daily school assembly, first thing in the morning. We were awed by his height, about 6' 3", and encouraged by his relative youth. We thought he'd give a long speech and thereby give us a clue as to the liberties we could take with him. Instead he simply said: "I think there's a job to be done here" and went about reorganizing the school, with the result that, during his tenure, Cranbrook became known for academic and athletic standards second to none in Sydney. He demanded self discipline and excellence, but also was constantly ready to help and encourage. When I matriculated, at age sixteen, he strongly urged me to repeat the year because of my relative youth; but in light of our financial circumstances, that wasn't possible.

I feel a deep sense of gratitude to other masters at Cranbrook. One I must mention is Ken Felton. His nickname was "Zunny," again of uncertain origin. He taught English and French--a kindly, cultured man with a quiet sense of humor. He took a personal interest in every student and had an astounding memory for their activities at school and their subsequent careers. He was, therefore, the ideal Secretary of the Old Cranbrookians' Association. He taught for almost sixty years at Cranbrook and kept on as OCA secretary until shortly before his death in 1989. He and his wife came to visit us here in Salt Lake City, and we worked with him in establishing the Helene Joklik Scholarship Endowment.

Joklik:

I should say a couple of words about sports at Cranbrook. Sports were compulsory, with practice three afternoons per week, beginning after classes at three-thirty, and matches against other schools on Saturdays. The team sports were cricket and rugby football. I wasn't too enthused about cricket, although I could play a straight bat, i.e. defend the wicket. My reputation wasn't enhanced when I got clobbered, in fact laid out, by the boy next to me during bat drill and the headmaster, Brian Hone, had to pick me up and help me stagger to the infirmary.

But I was enthusiastic about football. Rugby Union is a little different from American football, in that you don't have to weigh all that much and wear a lot of gear. Mr. Hone had me play the position I was best suited for, scrum-half. The responsibility of the scrum-half is to transfer the ball smoothly from the scrum, in other words, from the forwards to the back line. You have to be quick or you'll get killed by their two loose forwards, called break-aways. The only way to avoid them is to dive towards the five-eight, the first man in the back line, and in the same motion, with both hands, feed him a torpedo pass to get him on his way. The five-eight, under pressure, passes the ball out to the next man, the inner center, then the outer center and, if no breakthrough has been possible, out to the wing, the fastest man on the team. He attempts to outflank the opposing wing, or break through with the help of an extra man from the forwards or his other wing, and score a try.

After most matches, the skin would be gone from my hips, due to diving on the hard ground, but when you're that young it only takes a week to heal up. More serious was the occasion when I got caught under the scrum and broke my left arm. It had to be reset under X-ray which, at that time, was a fairly novel procedure.

I also made the school swimming and track teams. Mr. Hone had watched me train and decided that my stride was best suited for the 880 yards. I trained hard and became familiar with nausea of nerves before the start and the taste of blood in my mouth from exhaustion. But I loved the competition and the wave of euphoria from occasionally winning.

Joklik:

Both my brother and I were made house prefects in our respective final years. We both matriculated with two First Class Honors (mine in Latin and chemistry) and four A's, well within the top percentile of candidates in the state, and both won Exhibitions to the University of Sydney. Exhibitions were scholarships awarded by the state to the top 100 matriculants. [Interview 2: January 19, 1994)

My Cranbrook years were precious. They were tough years, without my father, and full of sacrifice for my mother. But the school provided us with learning, growth and friendships, for which I am grateful.

Swent:

So, after you completed Cranbrook, you and your brother were off to the university.

Joklik:

Yes. I went out looking for a vacation job and found one at a department store in Sydney as a gofer in the tailoring department. The job was ripping up suits that had been poorly tailored and running errands for the boss. There were U.S. warships in Sydney Harbor, and sometimes I was asked to deliver uniforms to sailors. I would go aboard one of those ships, find the sailor I was supposed to deliver the suit to and he'd want to give me a tip! I'd explain to him that this was unnecessary, that he'd paid for his uniform and he didn't need to give me any money. It was only after three or four fairly awkward encounters that I realized tipping was customary in America. The work was not demanding. It didn't pay much either, but it provided a little income which was appreciated. Then I began studies at the University of Sydney.

Swent:

This was in the spring of 1944 or '45?

Joklik:

That was the fall of '45. See, the seasons are reversed. The academic year started in February.

University of Sydney and Bureau of Mineral Resources, Canberra, 1945-1953

Joklik:

Commencing at the university was preceded by selection of a field of study. I had been attracted to the classics, especially Latin, but I recognized it was unlikely to lead to a career. I also liked chemistry, physics and math, which meant a choice between science, engineering and medicine.

Joklik:

It turned out to be a close call between science and engineering. I interviewed faculty members and decided to go for science. Math, physics and chemistry were mandatory. You were required to take four subjects, which necessitated picking an additional subject from among botany, zoology, biology or geology. I thought of botany, because Sydney University's Botany Department was headed by a man named Eric Ashby, one of the leaders in that field. He later went to Oxford and became Lord Ashby as a result of his brilliant research in botany and biology.

As it turned out, Professor Ashby went on sabbatical leave in 1945. I had an interview with him and regretted that I wouldn't have the chance to study under him. Under the circumstances, I decided to enroll in geology as the fourth subject.

I found a different culture at the university. At Cranbrook, courses of instruction were in relatively small classes, with much individual attention. University classes numbered a hundred, sometimes two hundred. The student body came from a variety of backgrounds. The environment was competitive because there were many returned servicemen, or veterans as we'd now call them. These men, and a few women, were several years older than the students who came straight from high school. I was only sixteen when I started at university, and most of these people were in their mid-twenties.

Swent:

They were already being furloughed out?

Joklik:

Yes. This was 1945.

Swent:

Had they been wounded?

Joklik:

A few. Entrance to university was competitive for the recent high school graduates. There was a quota system, based on academic performance at matriculation.

Swent:

And, of course, this was your first time having classes with women.

Joklik:

Yes, that was an interesting experience. Women were outnumbered by men ten to one, maybe fifteen to one, but they were noticed. Since the course load was heavy, there wasn't a lot of time for socializing, once the day's assignments had been completed.

I had regrets that I could not take the advice of Brian Hone, our headmaster at Cranbrook, or of Professor Ashby. Both urged me to repeat Sixth Form, the final year at Cranbrook. That would have been a relaxing year.

Swent:

You were very young.

Joklik:

After the first few months, that didn't bother me. I was in the swim. It really wasn't a difficult adjustment.

First year went well. I received High Distinction in geology, Distinction in chemistry, Credit in physics, Pass in mathematics. You could only get a Pass or Fail in math--a calculus course. I suppose the High Distinction indicates geology may have been the easiest course.

Swent:

Or that you especially liked it.

Joklik:

I was ranked first in that class, an indication that I should pay attention to geology. The department was in a separate, ancient building on the campus. The faculty was renowned. The department was headed by Professor Leo Cotton, a stately gentlemen who had achieved fame as an Antarctic explorer. He gave an introductory course in physical geology; the course material hadn't been revised for some time. I remember the discussion of the theories of Alfred Wegener. Professor Cotton told us that Alfred Wegener's then revolutionary theory of continental drift should therefore be disregarded. During the half century since then, Wegener's ideas have blossomed into the theory of plate tectonics which now governs geological thinking and instruction.

Swent:

So you were at least introduced to it, in a negative way, but--

Joklik:

It was an entertaining course. We had a demonstration of a geyser brought into the classroom and operated by a technical assistant who must have been in his seventies. We were both amused and impressed when this metal contraption periodically spouted up steam and water at the ceiling.

This was the year during which the war ended in Europe and Japan.

Swent:

It must have been an enormous relief.

Joklik:

Yes. It was. Australia was deeply affected by the war. The casualty rate was probably higher in Australia than in other countries on the Allied side. The Japanese invaded New Guinea and ran into stiff Australian opposition in the Owen-Stanley Range. Then came the Battle of Midway, the turning point of the war in the Pacific. Until then, there was a threat of invasion of the mainland of Australia.

Swent:

There was actually bombing in Sydney Harbor, wasn't there?

Joklik:

Yes. Darwin was heavily bombed. Submarines came into Sydney Harbor. These were midget submarines with two-man crews on suicide missions. They sent a torpedo under the keel of a cruiser and hit a supply ship which blew up. They also shelled the city. I still have a fragment of a shell casing I found.

During the summer vacation, at the end of first year, I got a job at the Sydney office of the Taxation Department. A bunch of university students were employed on a temporary basis to work with the local permanent staff who turned out to be a sociable group of young men and women. My job was to take each return, scan its contents and then write an identifying serial number on it. There was no such thing as social security numbers. We were given a certain quota each day. In four or five hours you could get that done and the rest of the time could be spent socializing.

Joklik:

I remember brilliant hot summer days, with the cicadas singing in the trees. At Christmas time, you had Christmas beetles invading gardens and sometimes houses. These were big bumbling beetles with beautiful golden brown wings and shells. You just picked them up and put them back outside. Everybody was fond of Christmas beetles.

Swent:

I hadn't heard of them before.

Joklik:

Then, second year at university began and soon afterwards, in March, my father returned from internment camp.

Swent:

And where had he been at internment camp?

Joklik:

In the state of Victoria.

Swent:

So you actually hadn't seen much of him at all.

Joklik:

Hadn't seen him for years. When he arrived at the little house where we lived, I hardly recognized him.

Swent:

Had you been able to write? Had your mother been in contact with him by writing?

Joklik:

Yes, there was an exchange of letters. But that didn't take the place of personal contact. It was difficult for him to find employment. The following summer, he went back home to Vienna, as did most of the other people who were released. It was tough, but he found his feet back there and with the help of former friends from Siemens started an export-import firm. He died young, at age sixty-seven.

Swent:

Did your mother go back with him?

Joklik:

Not at that time, but later she did. I had some wonderful times with my parents on visits back to Vienna. She died young, too. Anyway, what more can I say, except that I still miss them.

Swent:

A different kind of war casualty.

Joklik:

Yes, I guess. That's the way it went.

Swent:

Had he been mistreated in the internment?

Joklik:

Oh, no.

Swent:

Well, of course, it's mistreatment just to be there.

Joklik:

Second year university was a time during which geological excursions became an important element of the curriculum. We became a pretty closely knit group as a result of these trips. Some were just day excursions, others were three or four days at a time. Something to look forward to.

On campus, too, there were new friendships. Once a week there were movies at the University Union, at which comments on the movie being played were not discouraged. On one occasion, the scene was in Tsarist Russia; the guests at a banquet toss their champagne glasses over their shoulders against the wall. Just a week before, there was a student party at Palm Beach, just north of Sydney. The party got out of hand, involved broken glass and required police attention. So, as this scene took place on screen, I reminded the audience of Palm Beach, which caused guffawing. Social life did interfere with studies that year, and it required a big push, at the end, to recoup lost ground.

Joklik:

That summer I took a vacation job, again with a bunch of other students near Griffith in the Riverina of western New South Wales, an irrigation area which was farmed for citrus fruit, other fruit such as peaches and apricots, and vegetables. The land was irrigated from the Murrumbidgee River. As you know, once you get away from the coastline of Australia, water gets scarce. Permanent water courses in western New South Wales can be counted on the fingers of one hand.

Swent:

What was your job?

Joklik:

Several jobs, as a matter of fact. The temperature almost every day was well over 100 degrees. The scenery consisted mostly of plains with low, blue hills in the distance that shimmered in the heat. Even on a calm day, there would be dust devils, or willie willies as they were called, that worked their way across the plains. There were parrots of various kinds, particularly pink galahs that would start their concert early in the morning and awaken everybody with their shrieking. We slept in barracks and were awakened either by these birds, or by some practical joker who'd get up early and lob rocks on the corrugated iron roof of the barracks.

The work I did was varied. I started off fruit picking- mainly peaches and apricots. You'd be on a horse-drawn cart with a ladder on it. Occasionally the horse would move off with the cart and you'd be stuck in the tree and have to find your way down. The next job I had was loading fruit into rail cars. We packed fruit in 80-pound crates and then had to stack these crates to above shoulder height in these rail cars. I must have weighed all of 140 pounds. If you failed and dropped a crate, the supervisor would wonder aloud whether you were really interested in the job and whether you'd rather just take your pay and go somewhere else.

But we learned a lot. I learned to drink beer, Australian style, which meant fairly large quantities.

Swent:

Prodigious quantities!

Joklik:

We had with us a few ex-servicemen. We had a man named Joseph Aloysius Maxwell. He had been in both World Wars and had won the Victoria Cross and Bar. But, with the attention lavished on him by well-wishers, he didn't fulfill his potential in peace time. He was working odd jobs around the country. He and I became friendly, but I realized he wasn't going anywhere.

I continued to be interested in sports. Of all the British Commonwealth countries that played cricket, Australia then had a "dream team"--a team of excellence that probably has not been equalled. It was led by Don Bradman, regarded as probably the best batsman that's ever played the game. Others were Lindsay Hassett, Keith Miller, Arthur Morris and Don Tallon; also Ray Lindwall, who was then the best fast bowler in the world. This team had tremendous national support and its members became legends.

Joklik:

Then came third year at university during which I majored in chemistry and geology. We went on a geology excursion northwest of Sydney in the Armidale region of New England. The Professor of geology at New England University, an outstanding petrologist named Alan Voisey, was in charge. Fortunately, Alan was a kindly man. One evening we had been out partying and came back late to the hotel. As it turned out, a group of traveling salesmen had a party of their own and did some things they shouldn't have. We got the blame the following morning. Alan Voisey called us together and said that, since there had been a police report on the incident, he felt compelled to send us back to Sydney, which could have meant expulsion from University. Fortunately he believed us and let us off the hook.

Swent:

What was the potential at that time for geology? You wouldn't necessarily have had to go into mining.

Joklik:

There were three career paths in geology--mining, petroleum and academics.

Swent:

Were you beginning to get a sense then of direction and career?

Joklik:

Yes. I was beginning to develop an interest in mining geology.

Swent:

You mentioned that this man was a petrologist.

Joklik:

Alan Voisey? Yes. And perhaps I should take a minute and talk about a couple of other faculty members. The most senior person, after Professor Cotton, was W. R. Browne, who was an expert on magmatic differentiation. This is the process by which a lithological suite, ranging from acidic to ultra basic, is derived from an original magma. He was a widower, I believe. Later, he married our paleontology professor, Dr. Ida Brown. They were a popular couple.

Joklik:

At the end of my third year, I had my baccalaureate, my B.Sc., in geology and chemistry. During the summer of '47-'48, I took my first job related to my studies. This was with the Bureau of Mineral Resources in Canberra.

Swent:

This would be the equivalent of our former Bureau of Mines, perhaps?

Joklik:

Precisely. A branch of it was the nascent Geological Survey of Australia. Each state had a geological survey, but this was the federal government survey, based in Canberra. The permanent staff initially numbered only seven or eight geologists. The charter of the organization was economically oriented. It was meant not to duplicate the work of the state surveys, but to examine regions where ore deposits or petroleum reservoirs were likely to occur. The idea was to promote the mineral development of Australia.

Swent:

Quite an exciting thing to be involved in.

Joklik:

Yes. My first assignment was more prosaic and consisted of surveying a hill adjacent to the U. S. Embassy in Canberra. The embassy had just recently been built and was preparing for expansion.

Swent:

Canberra was just a new city at that time, wasn't it?

Joklik:

It was. Canberra was planned by an American architect named Burley Griffin. He laid out the city on a pattern of future shopping and business hubs, with residential communities in between and, ultimately, lakes or water reservoirs which would result from future dam construction. It was imaginative and, in retrospect, successful. At that time, Canberra had a population of 25,000. The city now has three or four hundred thousand. Back then, the residential communities were widely separated in the countryside. A car was essential to get around, but since we couldn't afford cars, we all rode our bicycles to get from our accommodations to our place of work and elsewhere. I don't know whether you've been to Canbrra.

Swent:

I have. I don't know it well, but I have just been there.

Joklik:

It's now a beautiful city. Anyway, we worked on this project by the American Embassy for a while. We were then deemed to have had our boot camp, so to speak, and were ready to go further afield. Bruce Walpole, a fellow student from the University of Sydney, and I were sent to Cobar in western New South Wales. Bruce was in the army throughout the war and became a lifelong friend. We still meet up and reminisce.

Joklik:

Cobar was an old copper and gold mining field about 450 miles west of Sydney, in the semi-desert. The town had about 2,000 inhabitants and featured six or seven pubs. Our work consisted of mapping the terrain surrounding the copper and gold mines and making sense of their geological setting, with a view to predicting other occurrences of mineralization. The mines were in a series of en-echelon faults along a discordant contact between Silurian slate and sandstone. If you could define this pattern and extend it, you could predict other foci of mineralization that might be worth detailed mapping and exploration by diamond drilling.

As it happened, Zinc Corporation, which later became one of the components of CRA (ConZinc Rio Tinto of Australia) , had a major exploration project in the area. They were assisted by a group of South African gee-physicists under the direction of Oscar Weiss. This crew had state-of-the-art equipment, and were in demand all over the world.

Swent:

Did you have direct contact with them?

Joklik:

Yes.

Swent:

So you were actually learning from them.

Joklik:

Yes. Because the summer was very hot, we partied extensively. There was a hospital there, a sort of bush hospital, staffed by nurses who were glad to join in our parties. I said to myself, "Boy if this is a geologist's way of life, it's not all bad."

Swent:

And you were what--nineteen? Twenty?

Joklik:

I was nineteen, I think.

Swent:

It must have been a pretty heady time.

Joklik:

Sometimes we'd watch the train which came in three days a week. The steam locomotive would come chugging along, trailing maybe half a dozen passenger cars and the same number of freight cars, doing all of twenty-five to thirty miles an hour. The locals, anticipating the kegs of beer that would come off the train, would appreciatively comment, "She's flying!" Only thirty minutes after the train came into town, beer from the kegs would be flowing through the refrigerated pipes in the pubs and the inhabitants would be breasting the counter, ready to savor the first drops. In between trains, sometimes, the town just ran dry, a tragedy that would cause great alarm!

We did succeed in making sense of the structural geology of the area. This work was right in line with my studies the following year.

Swent:

Then in your senior year you did a--

Joklik:

During my senior year I'd majored in chemistry and geology, and now I was contemplating an Honors Year, a fourth year, specializing in structural geology. I decided to do more work at Cobar and write my Honors thesis on this area.

We used to make beer money from rabbit shooting. This was before the days of myxomatosis, a disease imported from France to try and kill off the rabbit population of the country. Wherever you went in the Outback, you'd see countless rabbit burrows.

Swent:

Well, they tried rabbit fences, didn't they?

Joklik:

Rabbit fences, which the rabbits had no difficulty burrowing under. We'd go trapping at nighttime, clear the traps in the morning, skin the rabbits and sell the skins.

That summer was the beginning of my association with John Sullivan. He then was in charge of the Geological Survey's mining division. The first time I saw him was in his Canberra office. He came ambling along and I thought, "It's Gary Cooper!" He was a long, athletic streak of a guy, walking in a relaxed kind of way. We hit it off from the start.

John spent time with us in Cobar and guided our work. He was a very good interpreter of geological data, a great synthesizer of information. He would draw conclusions that were not initially obvious to others; but once he'd explained them, they would say, "Well why didn't we see that?" He is also a well educated person of broad interests including history, philosophy and international affairs. John has always been a person I could talk to for hours and feel I'd learned something. And that's still the case. He's retired now and lives in Toronto. We still keep in touch. He's one of the most highly regarded members of the Canadian mining community and has received many distinctions and awards.

Swent:

He must be several years older than you.

Joklik:

Fourteen years older. Our mapping at Cobar was based on aerial photographs. With the fairly sparse vegetation, you could identify individual trees. In terrain where normally you'd have to use a transit, or compass and chain, there you'd use enlarged air photographs. John taught us stereoscopic interpretation of photographs to pick out geological structures.

I went back to university to begin my Honors Year in structural geology. My supervisor was Professor George Osborne, an expert in structural geology. He was a formal kind of man, of stout physique and a prominent profile; but a warm person once you got to know him. He was an excellent extemporaneous speaker, you might almost say an orator. In my Honors Year, we were a very small group. He would, nevertheless, lecture in his academic gown, pace up and down and draw extravagant sketches on the blackboard as if he were addressing a much larger audience.

Once you had finished your baccalaureate, once you got into Honors and Masters and Ph.D. work, the curriculum was less structured than it was in the United States. You were expected to have mastered the basics of your field of study. Emphasis was placed on reading, analysis, individual work and initiative. George Osborne set a wide variety of tasks unrelated to his formal lectures.

Some time after the beginning of the Honors Year, I returned to Cobar to build on the work we'd done there in the summer. Osborne came out in the field. So did John Sullivan, and Haddon King, who was then Chief Geologist of Zinc Corporation. Haddon, John and I took a ride in a small, three-engine plane, called a Dragon Rapide, to survey the Cobar mining field from the air.

It was exceedingly hot, over a hundred degrees, and there was a forty-knot wind blowing. To see what we wanted to we had to keep low, no more than 1,000 feet above the terrain. You can imagine the turbulence. I got sick as a dog. Nevertheless, we were going to complete the survey. In between checking the inside of a brown paper bag, I did get a good look at the countryside. When we eventually put down, I was ready to go back to Col Halliday's place. Col worked at one of the mines at Cobar and I was staying with him and his family. I was glad to get to my little bedroom and crash without undressing. Later in the evening John Sullivan came to check on me and I told him, "They died with their boots on." Next day, I was perfectly fine.

I worked on my own there for several months. I had a jeep and a tent and camped out. On one occasion, after breakfast, I went out on a traverse, about seventeen miles north of camp. I was speeding across the plain when, suddenly, I saw in front of me a deep drainage channel. It was too late to do much, really. The jeep rolled over. I had the hood down and was lucky not to get crushed. When I recovered my senses, I found my thigh wedged against the ground by the steering wheel. I thought it was broken. I managed to extricate myself and found it was just badly bruised. It was late morning, and I limped the seventeen miles back to camp and even managed to do a bit of mapping along the way. That evening I hiked over to the property owner's homestead, another six miles away, and got a station hand to bring a truck. We used headlights to follow my tracks and pulled the jeep out of the ditch. Except for some spilled oil, there was nothing wrong with it, and I was able to drive it back.

Swent:

Good heavens!

Joklik:

It was a full day.

Swent:

It must have been very alarming.

Joklik:

I completed that project and then continued with my Honors Year studies at Sydney University.

Swent:

Did this project go into the geology files at the Bureau?

Joklik:

Yes. I wrote my Honors thesis on it.

The year finished with First Class Honors and the University Medal which is awarded in a discipline, once every few years, for outstanding work. I also received the Deas Thompson Scholarship.

Swent:

And the date of this was?

Joklik:

December 1948, when I had attained the ripe old age of twenty. The question was what to do next; whether to continue with the Bureau of Mineral Resources in a permanent capacity--my work at Cobar had been only a temporary student assignment--or whether to seek employment elsewhere. I sent off job applications to several places. One was to the Australian Petroleum Company which would have meant working on oil exploration in Papua New Guinea. They invited me to an interview at the company's headquarters in Melbourne, bought me lunch and offered me the job. I also corresponded with the Cerro de Pasco Company in Peru, with Tsumeb in Southwest Africa and the Emperor Gold Mining Company in Fiji.

In the end, I decided on further experience with the Bureau of Mineral Resources, based in Canberra. My first assignment was learning on the job. In the spring of 1949, a minor earthquake shook an area north of Canberra, centered on two small towns named Gunning and Dalton. Another new recruit and I were sent to determine the cause and investigate the damage which consisted of cracks in buildings, rotated tombstones in the local cemetery and some broken kitchenware and ornaments. Since there wasn't a history of previous seismic activity, the locals tended to be over-excited by the extent of damage and prospects of compensation. Their welcome to us cooled when they found that our mission was scientific, not financial. The quake, we concluded, was due to isostatic adjustment of a fault block we mapped.

Joklik:

About that time, the Bureau gained a valuable addition to its staff.

Dr. Armin Opik escaped from Estonia, where he had headed the paleontology department at Tartu University. He was a renowned expert on Cambrian trilobites and wanted to explore the Cambrian terrane of the Barkly Tableland which extends from Tennant Creek in the Northern Territory to Camooweal in western Queensland. I was volunteered as his driver and assistant.

We met up in Tennant Creek, a gold mining town of a few hundred inhabitants.

The town is in what's called bull-dust plains, on which cattle graze and grind the dirt to powder. When you're driving through, you're in a huge cloud of dust. Of course, this was in April, the end of the wet season; so there were flies everywhere. You couldn't eat during the day, because as soon as you opened your mouth you'd swallow flies. Despite the heat, you'd wear nets to keep the flies off. Finally in the evening, you'd take the fly net off and take something to eat. There'd be a respite of an hour before it got totally dark and the mosquitoes came out--in hordes. Between the flies and the mosquitoes, you always had company. The plains were covered with spinnifex, a spiky kind of grass that forms large clumps. Where you had to traverse on foot, your legs would soon be covered by spinnifex pricks which sometimes festered.

We started off from Tennant Creek, not before we'd had a large party, including a dance at the local pub. The son of one of the mine owners was a fellow named Ward Leonard, an active young man with long fair hair. He insisted on wearing his tuxedo to the dance in Tennant Creek! Towards the end of the evening he said, "Frank, why don't we have a drink back at the mine?" We drove back there, and emptied a few more bottles of beer and he said, "Why don't you sleep here rather than driving back to town?" I said, "Where am I going to sleep?" He says, "That's easy!" The beer was all gone but the straw casings were there, so he very carefully laid them out, maybe thirty in a row, and then another row and another; you can imagine in his state how long this took him and how funny it was watching him.

Dr. Opik and I headed east from Tennant Creek. We were highly successful in our hunt for trilobites. We found some localities where you just split the shale open and inside were perfect specimens. Even though I had never had much of a yen for paleontology, I was quite turned on by this exercise. One locality which I understand is still well known, we christened the Three-Beer Locality. We were camped by a dry creek-bed fringed by white ghost gums. We were awakened by galahs screeching in the trees. I got up and grabbed my rifle. One bird was sitting on a branch a hundred yards away and Dr. Opik said, "I'll bet you three beers you can 't hit him." I ruffled his feathers before he flew away. And this place became known as the Three-Beer Locality.

Dr. Opik was a highly cultured man, yet modest. He'd lost an awful lot during the war and afterwards, when he fled from the Russians. I remember in the evenings sometimes, when we had the campfire lit to cook our supper and to keep the mosquitoes away, he would wax poetic and recite Pushkin by the hour. He spoke Russian, as many Estonians do, and it was from the cadence of his voice that I guessed what the theme of the poetry might be, rather than the brief translations he'd give me periodically. I enjoyed my time with him.

Two or three years later, when I was living at a guest house about a mile from our office in Canberra, I'd been out to a party one night. At four in the morning one of my colleagues who was in the next room banged on my door and yelled, "The Bureau's on fire!" We could see flames shooting from the building. We flung on clothes, raced over and sounded the fire alarm. The building was pretty much gutted. But the tragedy was that Dr. Opik's trilobite collection was annihilated. You know, I saw him later that morning when everything was a shambles. I thought he would be visibly devastated. Instead, he surveyed the damage and said, "Well, we will have to start over again." What a man!

Swent:

What a tragedy!

Joklik:

We worked our way from Tennant Creek east across the Barkly Tableland to Camooweal, a small cow town of about 200, on the border between Queensland and the Northern Territory.