Oral-History:Donald H. McLaughlin

About Donald H. McLaughlin

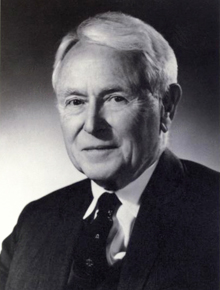

Dr. Donald Hamilton McLaughlin, an eminent mining engineer, was born in San Francisco in 1891. He took a bachelor's degree at the University of California at Berkeley in 1914, and quickly followed with a master's (1915) and Ph.D. (1917) from Harvard. He received honorary degrees from South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, Michigan College of Mines and Technology, Montana School of Mines and Colorado School of Mines.

He enlisted in the Army in 1917 and served as a lieutenant with the 63rd Infantry until the end of World War I. Returning to civilian life, he became a geologist with the South American firm of Cerro de Pasco Copper Corporation in 1919. Dr. McLaughlin was equally at home in a Harvard classroom, the board chambers of half a dozen powerful business corporations and the rough-and-tumble of the gold fields.

Donald McLaughlin, was the outstanding expert and spokesman in this country for the gold mining industry. He spent most of his distinguished career with Homestake Mining Company, one of America’s largest gold producers, where he played a key role in expanding gold reserves at the company’s mine in South Dakota. He began his long, inspiring career there in 1926 as Consulting Geologist and subsequently served as Director, President, Chief Executive Officer and Chairman of the Board. He served as a Professor and Chairman of the Department of Geology at Harvard from 1925 to 1941, and had a lifelong association with the University of California, serving as Dean of the College of Mining, Professor of Mining Engineering and Dean of the College of Engineering at Berkeley. A chair in mineral engineering was established in his name in the University’s College of Engineering. He served as Chairman of the Advisory Committee on Raw Materials and as a member of the Plowshare Advisory Committee of the Atomic Energy Commission (1947, 1972). He was a member of the Advisory Committee for the U.S. Geological Survey and of the National Science Foundation.

Dr. McLaughlin held Directorships in many companies, including Cerro de Pasco, International Nickel of Canada, Bunker Hill, San Luis Mining, and many others. He had said that his chairmanship of the Advisory Committee on Raw Materials of the Atomic Energy Commission during its first five years was an assignment which was particularly worthwhile. In addition, he felt his membership on the Board of Regents of the University of California provided him with many opportunities to serve in ways that were very satisfying to him.

McLaughlin received numerous awards throughout his career including; the Rand Medal of the American Institute of Mining Metallurgical and Petroleum Engineers (AIME) and the Ambrose Monell Medal of the Columbia University. In 1966, the California State Assembly honored him with a Resolution of Commendation. It is fitting that the largest gold find of the 20th Century in California was named the McLaughlin Deposit to honor this great engineer who dedicated his life to the gold mining industry.

Further Reading

Access additional oral histories from members and award recipients of the AIME Member Societies here: AIME Oral Histories

About the Interview

Donald H. McLaughlin: An Interview conducted by Harriet Nathan in 1970 and 1971, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1975.

Copyright Statement

All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between the Regents of the University of California and Donald H. McLaughlin dated October 25, 1972. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley.

Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the Regional Oral History Office, 486 Library, and should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user. The legal agreement with Donald H. McLaughlin requires that he be notified of the request and allowed thirty days in which to respond.

It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows:

Donald H. McLaughlin, "Careers in mining geology and management, university governance and teaching : transcript, 1970-1971," an oral history conducted in 1970 and 1971 by Harriet Nathan, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1975.

Interview Audio File

Interview

INTERVIEWEE: Donald H. McLaughlin

INTERVIEWER: Harriet Nathan

DATE: 1970 and 1971

PLACE: Berkeley, California

McLaughlin:

That's a formidable list of topics [referring to outline] but it does bring us back to the first part of the story. [Laughter] My father was a doctor in San Francisco, an M.D. He died in 1898 when he was two days over forty.

Nathan:

What was his name?

McLaughlin:

William Henry McLaughlin. Mother was a golden redhead with brown eyes, a lovely complexion — really a very beautiful young woman. She had to get a job and was employed by Phoebe Hearst just about at the turn of the century, after my father died.

Nathan:

And what was her name?

McLaughlin:

Katherine Hamilton McLaughlin. I don't know just how she got the job, but I think she was making some things for an organization that was called the "Woman's Exchange." Her work attracted Mrs. Hearst's attention and Mrs. Hearst asked her to do various things for her. That started an association that lasted until Mrs. Hearst's death about twenty years later.

My mother had so many different assignments, it is hard to say just what she was doing for Mrs. Hearst. Sometimes she ran the house at Pleasanton - the Hacienda - and handled some of Mrs. Hearst's secretarial work. At the time Mrs. Hearst spent a couple of years in Berkeley, my mother was there with her, looking after a number of things around the campus in connection with the entertaining that Mrs. Hearst was doing for the students, particularly the girls. Mrs. Hearst was disturbed that the co-eds in those days really had little good social life, at least as she saw it. Few of them seemed aware of the proper things a young Victorian lady should know! [Laughter] So she had a series of musicales and dinner parties, entertainment of that sort, rather elaborate in nature.

At first, Mrs. Hearst rented the Pennoyer house, then at Channing Way and Piedmont Avenue and built a large hall, designed by Bernard Maybeck, on a lot immediately to the west. The hall was used for a series of musicales and receptions. A group of tapes tries, known as the Coriolanus set, was exhibited in the main hall — indeed the form of the recessed windows and the sloping walls timbered with redwood shakes may have been planned with them in mind. The building was constructed so that it could be moved in segments, as it was later, to a site on the campus north of Bancroft Way and west of Piedmont Avenue. It was then remodeled to serve as a gymnasium for the women students. It was built of redwood — with heavy timbers and long shakes in place of the shingles that were so generally used in early Berkeley houses. It was one of Maybeck's most remarkable and successful structures. It burned down more than thirty years ago. Mrs. Hearst also spent a winter in two houses now standing in the wedge between Scenic Avenue and LeConte Avenue, just south of the top of what some irreverent people now call Holy Hill. The Benjamin Ide Wheelers then lived in the house on Scenic Avenue immediately to the south. Mrs. Hearst, I believe, owned the crest of the hill west of the intersection of Scenic, LeConte and LeRoy Avenues, but later decided not to build, and sold the ground which was eventually occupied by one of the schools of religion.

And I think Mrs. Hearst founded a couple of living clubs for women in Berkeley. I am not sure if any of them have survived. I really don't remember much about them. But she was very anxious to improve the life of the young women on the campus . Mother was very much involved with her activities at that time.

Nathan:

Your mother sounds versatile and like a good person to have around. She apparently could do whatever was needed.

McLaughlin:

Yes. I think she had a very nice way of getting along with people. She really was an attractive person. When she died, just before her 89th birthday, her hair was still half red, and half white.

McLaughlin:

I called her a strawberry roan, if you know that type of horse. I had reddish hair when I was a boy, but my father who had dark hair was quite white when he died at 40, so I inherited my white hair from him, even though I had my mother's reddish hair.

Nathan:

I think you had the best of both! [Laughter] Tell me a little more about your mother. Where did she grow up?

McLaughlin:

Both my mother and father were born in Folsom, California. That was before the prison was built there, I hasten to say. Their parents were pioneers who came in the '50s. I haven't really made much effort to study just what they did or where they came from, except that my father's mother was English. I remember her telling about coming across the Isthmus. She always called it "The Isthmus of Aspenwall." The town on the Caribbean side at that time was named Aspenwall, after one of the builders of the first railway. It's now called Colon. It seems so typically English for the little girl to remember the place as "The Isthmus of Aspen wall." That was before the railroad was built — or at least before it was completed and functioning — for she said she was carried across some of the marshes on men's backs. She survived the mud and the fever and eventually reached California. I really must look into the family records a little deeper.'

Nathan:

Only if it interests you. I'm sure your interests lie in many directions.

McLaughlin:

I am afraid they do. But I am sorry that I haven't paid much attention to my forebears.

Nathan:

Was your father educated in California, then?

McLaughlin:

Yes. He came to San Francisco and went to a medical school which I think is now defunct. It may have been a forerunner of the Cooper Medical College. A life-long friend of my parents was a fellow student of my father, Dr. 0. D. Hamlin, whose son is Judge Oliver Hamlin.

Nathan:

I see. Did you have any brothers or sisters?

McLaughlin:

No. I'm an only child.

Nathan:

Did you live in Berkeley, then, before you went to Pleasanton?

McLaughlin:

No. We lived in San Francisco. After my father died, my mother and I lived with an aunt in Oakland on what was then called Albion Street, which at the time, was an attractive tree-lined street. The house was between Telegraph Avenue and Grove. It was a street of nice, old gingerbread houses with really attractive gardens. It has become, of course, a very down-at-the-heel neighborhood since then. I took Jeanie and George down there a year or so ago to show them the old house and found nothing but the freeway that now slices through the area. The house had completely disappeared. In those days, it was really not far from the northern edge of Oakland. Between there and Berkeley was a good deal of empty country then.

I remember going to Sunday School at a red wooden church that is still standing on the corner of 29th Street and Telegraph Avenue. It still gives a little of the feeling of that old part of town — lovely trees and gardens. But how the area has changed!

Mother then was living most of the time with Mrs. Hearst and was in Washington with her one winter.* I was living with my aunt and going to school in Oakland.

Nathan:

What was your aunt's name?

McLaughlin:

Mary Frances McLaughlin. She was my father's sister. She was the guardian of an elderly and gentle old person named Gee, who had been declared incompetent. He was well-off, and he had no relatives. The court appointed my aunt his guardian, and she looked after his house and affairs.

After his death in 1902, my aunt and my grandmother joined us in Berkeley, where my mother had built a house — a flat — at 1629 Euclid Avenue between Virginia and Hilgard Streets. It was one of the first houses in Berkeley designed by John Galen Howard. David Farquharson, who had done some work for the University and also for Mrs. Hearst at the Hacienda, was the builder. Mother lived there until the house was burned in the big Berkeley fire of 1923, after which she moved to an apartment at 1403 Hawthorne Terrace and later to 1435 Hawthorne Terrace. When I came to Berkeley as a dean in 1941 I bought the house which had been built shortly after the fire by my old High School teacher known as "Pop" Clark.

The Hearsts lived at 1400 New Hampshire Avenue when George Hearst was in Washington as a Senator. After his death, Mrs. Hearst kept the house for several years, during which time she was particularly interested in the organization (largely made up of women) that preserved Mt. Vernon. I think she gave the money for a "sea wall" to check erosion of the low cliff facing the Potomac. Her activities in the Parent and Teachers Association date from this time also, I believe.

McLaughlin:

Of the first really steep hill, everybody travelled by street car then. The trolley cars were really very convenient. I don't believe there were more than a dozen houses above the steep hill on Euclid Avenue that goes across Cedar Street. It was just empty country beyond there. A quarter of a mile farther up, there was a farmhouse with some cypresses around it — a hundred yards or so southwest of the reservoir. The owners always put out a bucket of water from their well for the hikers who passed by. A road that became quite steep took off from there over the ridge to Wildcat Canyon, which is now part of Tilden Park.

That was a very nice place for a boy to grow up, with the hills to hike in and steep streets to coast on. Perhaps that's why I have such a warm feeling for Berkeley.

Nathan:

Yes, I was thinking as I came up to your house this morning that out of all the places that you've seen in the world, you have been faithful to Berkeley,

McLaughlin:

My loyalty gets a bit strained these days by the antics of the Berkeley City Council — but we're still here.

Nathan:

Do you remember the name of the grammar school you went to when you were living in Oakland?

McLaughlin:

Yes, It was the Grant School that was on Broadway at 29th Street on the N,E. corner. It was an easy walk from where we lived on Albion Street, across a little low hill. Of course, to a child it seemed a rather impressive hill, particularly with the several large mansions at the top. One of them was the Mollers. A daughter of that family — probably more than ten years older than I — was Lillian Gilbreth, part of whose remarkable story is told by a couple of her children in the book and movie, Cheaper By The Dozen. I didn't know them very well, but I remember being in the house a number of times when I was a little boy. On an adjacent street, called Summit, there was also a line of nice houses, in one of which one of my best boy hood friends, Edward Veitch, lived. And so I was up on that hill a good deal. Now, it's become "Pill Hill!" It's all completely transformed from an area of old mansions to the complex of hospitals and shops that it is today. I doubt if any of the old houses are left.

McLaughlin:

After we moved to Berkeley early in 1903, I completed the fifth grade at the Grant School which required a long trip by the Tele graph Avenue trolley each school day.

The next term, I entered the McKinley School in the sixth grade The old wooden building is still standing on Dwight Way. It meant walking across the campus from our house on Euclid Avenue on the north side which was a good bit of exercise. I remember a little boy asked me one time — this was way back in the '20s— where I had gone to school. When I told him the McKinley School he looked me over and said, "Gee, I didn’t know Berkeley was that old!" I must have looked even more ancient than the old school then. [Laughter] I suppose that old building will be torn down pretty soon. It's not a school any more. I think it has recently been condemned.

Nathan:

Yes, although I think there are some classes still being held there - part of the Berkeley High School complex. But I always expect it to give a sigh and fall down.

McLaughlin:

Yes, it was old when I went there. And I remember the Anna Head School also looked old when I was a little boy. [Laughter] It's still there, and it still looks old.

Nathan:

It's now the Institute of International Relations.

McLaughlin:

Oh, they're in that? Rather a strange transition! I remember how unpopular I was with Mr. and Mrs. Daniel Dewey. This is an aside, but when I was on the Regents' Committee on Buildings and Grounds, it was decided that the University really would eventually have to have that land. Consequently, we didn't want the school to put a new and expensive set of buildings there. The Deweys were very much opposed to selling. As you know, it has since become a perfectly impossible neighborhood for a girls' school with Telegraph Avenue what it is today. It was a great piece of luck for them that the University bought it. Of course, the buildings were of rather little value, but the property was very good, and they received a fair settlement for it. We really did them a very good turn, but it wasn't appreciated at the time.

Nathan:

About what year was this , do you recall?

McLaughlin:

It must have been in the late '50s. There was no pressure put on them to get up and leave in a hurry, but it had to be made clear to them that the school eventually had to move. I think at that time it was changed from a proprietary school to an institution with a Board of Trustees that could function more easily as a non-profit institution. This led to the erection of the attractive buildings on the site the school now occupies in the hills above East Oakland.

Nathan:

You may have forced an important decision at the right time.

McLaughlin:

I think so. It's too bad they couldn't get some property in Berkeley to maintain the tradition. I think they looked at a number of places, including the old Garber house in the Claremont district. It would have been a fine place for the school. I don't know what blocked it. I suspect the neighbors. It's too bad we didn't keep the school in Berkeley, but it's got a good site and it's still an important institution. But I remember I was awfully unpopular with Mrs. Dewey at least! [Laughter]

Nathan:

I dare say they're reconciled by now.

McLaughlin:

Oh, I think they might be. But of course they are not with the school any more. They built the new school, however, and got it well started at the other place.

Nathan:

He has even retired from the Berkeley City Council now.

McLaughlin:

Yes, unfortunately. Well, they're very nice, friendly people.

Nathan:

It's interesting that you at least contributed a daughter to the Anna Head School.

McLaughlin:

My daughter, Jeanie, is one of the few who started in the first grade in the old buildings and continued right through to the twelfth grade in the new school.

Nathan:

I see. Now is Anna Head's a day school, or a boarding school?

McLaughlin:

It's entirely a day school now. It was originally a boarding school. It was a good thing to get the children out of the old wooden building, for the fire hazard was really serious. I feel less concerned about the Institute of International Relations I

Nathan:

Right. Now, did I ask you whether you remembered your grandparents?

McLaughlin:

Just my paternal grandmother; the other grandparents had died before I was around.

Nathan:

We had got past your grammar school. Now high school then would be next.

McLaughlin:

I entered Berkeley High School in the autumn of 1905, when I was 13 years old, just to be there in time for April 18, 1906, which was the big earthquake. That earthquake fortunately happened, you know, about 5:15 in the morning. The massive chimneys of the old brick building fell right down on the two stairways of the high school. There would have been dozens of children killed if the earthquake had happened when the building was occupied. I remember great holes in the roof when we went down to see the school later that morning. The school was standing, of course, but the huge chimneys had come down directly on the stairways. The school was so badly damaged that for the rest of the term classes were held in various churches around town, and in other scattered rooms.

Mrs. Hearst was in Paris. Mother hired a car and drove down to Pleasanton to see what had happened to the Hacienda. The old house wasn't hurt very much. Some fireplaces had fallen out, and one or two of the big flower pots that lined the roofs had been knocked over. Fortunately they fell out and didn't break through the roof, so the house wasn't damaged very much.

But here in Berkeley, two of our chimneys were knocked off. The earthquake was really the strongest one I have ever experienced here or even in Peru. We watched San Francisco burn for three days. It must have been eight or nine in the morning when we first noticed a tremendous column of smoke rising above the city. It looked like the pictures in the old geography books of an eruption of Mt . Vesuvius.

Nathan:

Last days of Pompeii!

McLaughlin:

Yes. A great cloud of billowing smoke — like a cumulus cloud.

Nathan:

Was it black smoke?

McLaughlin:

No, it was white-ish; you see, condensation from the rising hot air made a great cloud, like a thunder head over the City. After the first day, the fire spread out and the smoke was everywhere. At night, the sight from Berkeley of the flames and the reflection in the sky and in the bay was really terrifying. The first night the fire was all behind Goat Island (Yerba Buena Island) as we saw it from north Berkeley. The island was silhouetted against great flames shooting up above it. The next night the fire from our angle was on both sides of the island. I think that was when the Fairmont Hotel burned. Then came still a third night of fire with flames still farther out.

There were a number of earthquake shocks — after-shocks -- that kept us on edge. I remember one about eight o'clock the first morning that set our wooden houses rocking. Very few of our friends from San Francisco turned up on the first two days. They were driven by the fires to the other side of San Francisco and it wasn't until it was possible to get down to the ferries that a few came to us in Berkeley. A good many refugees from south of Market, however, escaped to Berkeley. Tents were put up on the campus for them. It was a dramatic time. I should have been more venturesome and gone to San Francisco, but it seemed better to stay home. [Laughter] Sightseers — especially fourteen-year-old boys — were not exactly wanted anyway. And fortunately there was no fire here.

Nathan:

You were speaking of the effects on the Berkeley High School building- was that located where Berkeley High is now?

McLaughlin:

It's on the same corner as the present school. The old building was repaired and I continued in school there.

McLaughlin:

Well, to go on with the story, Mrs. Hearst then cabled us to come over to France, to join her in October, which we did, crossing from New York to Cherbourg on the Hamburg-American liner, Amerika. We had a lovely time there. She had a very beautiful apartment on the Place de l’Alma, numero 1 bis.

Nathan:

Oh, yes. There's a bridge there.

McLaughlin:

Yes - the Pont de l’Alma was one of the most graceful of the Paris bridges, but unfortunately, the arches were so low that they were a hazard in times of flood. So the old bridge has now been replaced by a single steel span wider and higher, but far less beautiful than the three stone arches that were torn down.

I was fascinated with an old hydraulic elevator in the building. It had a long shaft that pushed an ornate cage up and down very slowly. [Laughter] I was the only boy in the household, and I just couldn't be dragged around on shopping tours with the ladies who seemed very elderly to me. So I went off on my own and really explored Paris very thoroughly, riding up and down the river on the boats, and to the end of the Metro lines — the subway — as well as taking trips on the double-decked steam trams. I remember accidentally getting down to the Isle de la Cite and seeing Notre Dame for the first time without knowing where I was or what it was. I was very excited at having made this discovery! [Laughter] I explored Notre Dame from the top of the towers to the crypts. Then later I remember Mrs. Hearst officially taking me around to show me the sights and I'd seen practically everything already - and probably a bit more than the rather formal old ladies had ever seen.

So I really acquired a geographical sense of Paris that's always stayed with me. In fact I feel I know just where I am today in Paris

Nathan:

Did you have any French at your command at this time?

McLaughlin:

Not very much. I'd taken one high school course in French; my French was terrible, but enough to ask questions. My ability as a linguist is very poor anyway, but I've managed to get around. I found when I was back in Paris in the latter part of the war, my knowledge of the geography helped a good deal, though I had a lot of new things to learn at that later age! [LaughterJ

In the late autumn, we visited Chartres and then drove through the chateau country in the Loire Valley in Mrs. Hearst's “Itala," an open touring car that in those days was the last word in elegance and speed too. Even though I was a rather young boy, the great cathedral and the gracious chateaux gave me a feeling for lovely structures that I think has stayed with me all my life. Even the excitement of driving in the Itala, which was a novel experience for a boy before automobiles were common, wasn't enough to make me for get the architecture we saw.

Dr. and Mrs. Joseph Marshall Flint — she was Mrs. Hearst's niece and a very lovely person — made the trip with us.

We then went to Italy for part of the winter, where we spent a month in a villa on the Island of Capri with the Richard Walton Tullys. Tully was a playwright. He wrote "The Girl of the Golden West," and a couple of other successful plays. His wife was Eleanor Gates, who wrote at least one fairly successful novel, though not a best seller. They were relatively young people, both of them Berkeley graduates, who started off in a very great way and then went over an early peak and didn't do much afterwards. I don't know just when they died. He had been the Yell Leader when he was on the Berkeley Campus.

Nathan:

In what part of Italy did you spend most of the time?

McLaughlin:

Capri - near Naples. It is now a rather crowded resort. We had Elihu Vedder's villa. Elihu Vedder was an artist of great fame then, though perhaps scarcely remembered now. It was an interesting house, called the "Torre Quattro Vente." We spent about a month there. Then again on my own, I explored Capri from one end to the other, made friends with boatmen, poked into all the little grottos and had an exciting time. The island was perfectly fascinating to me. I haven't been back since. From the tales you hear, life on Capri today must be very different but it must still be a beautiful spot in spite of the multitude of visitors.

Nathan:

Yes. How did Mrs. Hearst know Mr. Tully and Eleanor Gates?

McLaughlin:

I think she knew him when he was a young playwright, shortly after he graduated. She was always interested in young people, and here was a talented young fellow and his wife who deserved help. She really got them started on their careers.

Nathan:

I see. Was it during this period that she found the well-curbing?

McLaughlin:

No, that was earlier. That must have gone back to the '90s. I don't know when she bought it, but the curbing was in the center of the patio at the Hacienda as far back as my memory goes.

Nathan:

I hope you're going to talk some more about Mrs. Hearst and about the Hacienda, too.

McLaughlin:

Yes, she was a very important person in my life and my memory of her is a very happy one.

Now with the burning down of the old place, you know, about six months ago, there aren't many relics of that chapter left.

Nathan:

It was called the "Hacienda del Pozo de Verona” is that right-?

McLaughlin:

Yes, "The House of the Well of Verona" named after the well-curbing she acquired in Italy and placed in the center of the patio at the Hacienda. It's a particularly graceful piece of carving. After her death, her son moved it to San Simeon where it now is. I don't know the date of the curbing, but I imagine it's something around the 15th Century. It was carved out of limestone — almost a marble. You can see it at San Simeon in the lower plaza on the southwest side. Really a lovely thing.

Nathan:

My little Spanish-English dictionary gave the definition of "pozo" as either "well" or "mine shaft". I thought mine shaft was very appropriate.

McLaughlin:

Yes. Very. That's an interesting point — that is true. A mine shaft in Spain and Latin America is called a "pozo". Unfortunately, there was no mine shaft at the old Hacienda! Or even a well. There was no well in the patio — just the well-curbing. If you've been in Venice, you've seen that nearly every plaza has a somewhat similar curbing around a well. That's the way Venice got its fresh water. Some of the well-curbings have a little iron work above and a wheel, so that the buckets could more easily be lifted, but on this well- curbing now at San Simeon you can see the grooves around the side worn by chains as the buckets of water were pulled up. Look at that when you're at San Simeon next.

Nathan:

Yes, I will.

McLaughlin:

Mrs. Hearst had her own flag station on the Southern Pacific railroad in the valley below the Hacienda. It was called, "Verona." And I noticed when I went by the other day that the road across Laguna Creek opposite the site of the old station is called, "Verona Road." So that name is still there.

Then when the Western Pacific railroad was built through the fields below the house, a station on that line was named "Hacienda". In my early years — that is, back when I was a little boy in school and high school — not many had automobiles and nearly everybody went down by train. It was a little bit awkward from Berkeley. I did that so often. You'd go down to First and Broadway in Oakland on the trolley and then take the train there that went through Hayward to Niles and up the Niles Canyon. The train would let you off at the flag station. On the weekends, at least in the first decade of the century there 'd be half a dozen, if necessary, shiny carriages with beautiful horses, coachmen, footmen on them. You'd be driven at a lively trot up the road through the lower gates and up to the house on the hill. There were then only a few farms in the area.

Nathan:

How long did the train ride take?

McLaughlin:

It was about an hour's ride — generally a little more than an hour.

It was not then a main line, though I think that the railroad through Niles Canyon was the original line of the Central Pacific into Oakland. Most of the trains were locals stopping half a dozen times on the way down.

McLaughlin:

After the automobile became more common, however, most of the guests would go to Pleasanton on the train and then be driven by car from there. It didn't take much longer. Even in my college years, the automobile was gradually replacing the train.

When Mrs. Hearst gave a big party for my class in 1914, she engaged a private train, a long one — on the Western Pacific — that brought all the students, all the class, to the Hacienda station where there were cars and carriages to take them up to the house.

Nathan:

Was the fact that you were in the class part of the reason she gave the party?

McLaughlin:

[Laughing] Well, perhaps! She had had parties before for classes, but this was a very special one. It was a very nice occasion.

Nathan:

How many were in your graduating class?

McLaughlin:

I think about 600, and I don't know how many went down there. Probably most of them.

Nathan:

Imagine giving a party for 600 people! There's something very princely about it.

McLaughlin:

Yes. It was. I had, of course, a lot to do with the arrangements and so on; getting things organized. There was a big circular tent over the patio supported by a great pole in the middle rising from the well-curbing. The tent spread over the driveway that was covered with a floor and circular table on which lunch was served. Every body seemed to have a good time, especially a few who raided the wine cellar without attracting any attention. When the class held its 25th anniversary, most of the survivors and their families revisited the Hacienda which had then become the Castlewood Country Club. We had a pleasant party, but of course it was far from being on the scale of the one in our Commencement Week. Things had changed a great deal. It was a bit nostalgic, but everybody seemed to have a lively time. Unfortunately, one attractive girl, to whom I was being mildly attentive, brought me up to date by telling me that I was mistaking her for her mother. The Club didn't live up to its possibilities; it was rather messy, I thought, but they had at least added a fine swimming pool.

Nathan:

Were those the original buildings?

McLaughlin:

Yes, the central building was there, but they had made additions and modified it so much that most of the charm of the old house was lost. There were only a few little spots that seemed familiar. They did keep most of the patio. After the recent fire, all that is left of the house now is the front wall of the patio and the original gates. I presume they will soon be torn down. The rest of it is all burned. The big music room at the south end is still standing. That was a later addition by Mrs. Hearst. A rather unattractive house some dis tance away that was called "The Boys' House" is still there. These buildings were not part of the original design. The original design was by an architect named Schweinfiirth. He did a number of good houses in Berkeley also. He did the original Unitarian Church, you know, on Bancroft Way. It was threatened with destruction to make room for some of the units of the Student Center, but fortunately, it escaped. Another of his buildings is the fraternity on the corner of LeConte and LeRoy— a clinker brick house with an arched bridge across the creek in the front of it. His original design of the hacienda was really very lovely. A central three story structure stood on the east side of a large patio that was enclosed by two low wings on the south and north and by a smooth wall on the front. The patio was bordered by pergolas supported by thick white columns. The central part of the house was topped with two small, squarish towers. The roofs were flat for the most part. There were large red terra-cotta pots on the corners for ferns and flowers and little palms. Flowers dripped down the walls from them.

Nathan:

Lovely. This was a U-shaped house, then, I take it?

McLaughlin:

The house itself was U-shaped, and then the end of the U was completed by a blank wall with a coping of tiles that was pierced by a heavy gate flanked by two roundish towers . As you came up the road along a palm-lined driveway that curved with the contours of the slope, a sharp right-hand turn over a causeway led the road directly to the gates of the patio. The carriages went through the gates into the patio, and around a drive circling the Verona well-curbing.

It was really a very lovely entrance. The carriages all came to the front door inside the patio. At night the outside gates were closed — quite in the Spanish tradition.

The other side of the house had a series of three terraces with rather stubby, thick columns, again with successive rows of big earthenware pots with flowers rising from a big porch on the ground floor, from which there was a lovely view over the valley to Mt. Diablo. The view, of course, gradually disappeared as the trees grew up around the place.

The first room one entered from the front door was called the hall, but it was really a large living room with a big fireplace in the middle. Doors and windows opened to a broad porch on the valley side. A room called the library was on the right — a charming, smaller room. The dining room and kitchen were off to the left of the hall — that would be to the north. Beyond the library, a narrow hall called the lobby led to a billiard room, and then to a wing with bedrooms . The so-called lobby was lined with book cases. There was an early set of Dickens, illustrated by Cruikshank, and also a complete set of Punch that I found most entertaining and instructive. Also a set of Thackeray and Mark Twain, too; all of which helped me overcome my lack of courses in English and history.

In the opposite direction beyond the dining room was a long pantry leading to the kitchen and servants* quarters. There were three floors in the central house. To the north there was a separate house, also attached by a corridor with thick rather stubby columns and a tiled roof. Part of it was a tallish tower which was originally a water tank, and a lower house that eventually was made into a dwelling too. Then in the other direction, Mrs. Hearst had added a big music room. Julia Morgan came into the picture later and designed an addition to the music room that included a couple of handsome bedroom suites,, one of which Mrs. Hearst occupied for a few years before her death. The music room and the Julia Morgan addition are still standing. It's mostly brick, and it didn't catch fire.

Nathan:

As you looked at the building itself, was it mostly stucco or brick?

McLaughlin:

It was mostly stucco, white, with coping of red tile on the walls and with some completely tiled roofs; most of them just tiles on the top of the walls, the way an adobe building would have its walls protected by tiles with a flat roof behind it. That's the way the house was laid out. Here's a rough sketch of it.

Nathan:

It sounds very welcoming.

McLaughlin:

It really was. It was an extraordinary house and I think it would have beep, as well worth preserving as a state monument as San Simeon was later if it could have been taken just as it was at the time of her death. In her Will I think she specified the house and the land should be sold, and it was. I really don't know what the financial arrangements were, but it ended up as the Castlewood Country Club. It went through various vicissitudes, re-financing and so on, but the property has become immensely valuable because the club is now surrounded by an area of attractive country houses.

Nathan:

How much land surrounded the house itself?

McLaughlin:

There I would have to check, but I think there must have been a thousand acres in the ranch, for it included some farm land in the valley below, as well as the steep, wooded slopes of the ridge to the west. At that end of the valley there was artesian water. Wells went down and hit deeper gravels in which the ground water was under pressure, held in tight by the overlying silts. There were a half dozen wells there that spouted water. That was of course an immensely valuable asset in California, and I rather imagine it was one reason why George Hearst was attracted to the property. Eventually the Spring Valley Water Company acquired the rights at that end of the Livermore Valley to provide water for San Francisco, but a very generous allotment of water was made to the Hearst Ranch in the deal, what ever it was.

McLaughlin:

So, the ranch had a large quantity of water available. To pump it up the hill, a power-house was built, which is still standing though the building is a wreck now. It is on the road at the base of the hill. The building had a stack for an oil-fired boiler. The plant consisted of a one-cylinder steam engine that turned a dynamo to supply electricity and also pumped water up the hill. I don't know what became of the machinery. They would be museum pieces today. I don't think the machinery's there, but the old building is still standing.

Nathan:

This was really a self-contained little domain.

McLaughlin:

It really was. It was something of a principality.

Nathan:

Right. "The Duchy of Pleasanton?"

McLaughlin:

It was very much like that, and Mrs. Hearst presided over it in rather a royal way, you might say. [Laughter]

Nathan:

Something very engaging about the whole picture.

McLaughlin:

Yes. Something that just couldn't exist now and was on its way out even then, I imagine. After all, she inherited a huge fortune from George Hearst who was one of the great mining men of the times . His record of acquiring major mines has never been matched. That was before the days of income tax, so the large income from the mines, which was largely left to her, made it possible to live in that way.

Nathan:

Did you ever meet George Hearst?

McLaughlin:

No. He died the year I was born — 1891. So I never met him.

Nathan:

Just sort of overlapped. Maybe there is such a thing as transmigration of spirit! [Laughter]

McLaughlin:

He must have been really an amazing person. One of his earliest properties was a mine on the Cornstock, which started the family fortune. He'd had some smaller mines on gold-bearing quartz veins before that in the Grass Valley and Nevada City region. He made some money out of them, but none became really important mines . The mine on the Cornstock, the Ophir, in which he had a substantial share, made his first fortune; then he acquired for himself and his associate — J. B. Haggin in San Francisco — the Ontario Mine in Park City, Utah, which became a major silver and lead producer and a very successful venture indeed. It is still a producing mine. Unfortunately, his successors sold out before its full potential was recognized. Hearst and his associates were also the dominant people in the original Anaconda Mine at Butte Montana, out of which grew the Anaconda Copper Company. The Hearst- Haggin shares were sold seven years or so after Senator Hearst's death. And a little earlier than the Anaconda, he had gone to the Black Hills of South Dakota shortly after gold had been discovered near Deadwood and acquired a block of claims that covered most of the great Home- stake ore body.

Nathan:

Oh, yes. We're going to go back to all of these. It's good to know about them.

McLaughlin:

We're getting a little off the track perhaps I

Nathan:

It's all so fascinating, and we'll sort these things out as we go. Shall we go back a moment to Pleasanton? Was it a working ranch?

McLaughlin:

Yes. But not anything of great importance. There were vegetable gardens down in the valley worked by skillful Chinese gardeners; they supplied marvelous vegetables that I think were consumed entirely by the household. There was also a big vineyard with table grapes.

I don't think they sold any, but boxes and boxes of grapes were sent to Mrs. Hearst's friends. When I was a graduate student at Harvard, I had a box of grapes in sawdust sent to me nearly every week. [Laughter]

In the autumn. They were lovely grapes, too.

Nathan:

Were any for wine?

McLaughlin:

No they were table grapes - muscats and a great variety of dark and red grapes, all table grapes. Most of the rest of the land that was cultivated was just for hay.

Nathan:

Were there horses?

McLaughlin:

Yes, there was an elaborate stable an eighth of a mile or so away away from the main house. It too was burned down - five or six years earlier than the recent fire. There must have been about eight or ten stalls for horses, maybe more, and a big carriage room. I've often thought what a museum that would be if it could have been just kept intact as it was. The carriages would now be hard to duplicate. They weren't used much after the automobile age arrived and I don't know what happened to them after her death. Nobody appreciated the value of things then that were to become antiques in a few decades.

Of course the time came even before Mrs. Hearst's death when nobody used carriages. She had several automobiles even as early as 1905. I remember one of the earliest was the Italian car called an "Itala," and then there was another car, the "Hotchkiss," an English car. They were all funny little cars by present standards and they would all be valuable horseless carriages today. [Laughter] I think the first car I ever drove was a "White Steamer," which she had somewhat later.

Nathan:

Is that different from a Stanley Steamer?

McLaughlin:

Yes, but it was the same vintage. Somehow or other one hears very little about the White Steamer, and yet it was a standard car in those days; competed quite well with the gas cars. A very smooth-running thing, as I remember. That was the first car I ever drove or tried to drive.

Nathan:

That's a marvelous place to learn to drive.

McLaughlin:

Yes, out in the country on the dirt roads or gravel roads.

Nathan:

How old were you, then, when you were beginning to drive?

McLaughlin:

Let's see--I think that must have been in my high school days. I must have been about 16 or so, something like that. I don't think you had to have licenses in those days. Oh, I didn't do very much driving, but the chauffeurs showed me how to handle the car and let me run it once in a while which was a great thrill, of course. [Laughter]

Nathan:

Thinking again of the carriages—did they have two horses to pull them?

McLaughlin:

Yes. There was one--a big tally-ho--that had four horses, but it was very seldom used. That was something of an occasion if it was ever brought out. Practically all the other carriages were for two horses.

Nathan:

Did Mrs. Hearst have any sort of insignia on the doors?

McLaughlin:

Yes, her initials - PAH - in a rather elaborate monogram on the bridles and on the doors of the carriages. Some were closed, some were open.

Nathan:

How old were you when you first went there?

McLaughlin:

I must have been eight or nine years old. There are some letters from me to Mrs. Hearst, thanking her for weekends at the Hacienda, in the collection of her papers in The! Bancroft Library. I think the earliest is about 1900. Oh, I enjoyed it all so immensely. And then there were saddle horses. The chief recreation down there for youngsters was horseback riding, or hiking. There was a tennis court, but not much else in the way of sports. Two swimming pools were put in somewhat later. They would seem rather primitive by our present designs. The water in the first outdoor pool was extremely cold as you would expect artesian well water to be. Another pool later was practically part of the house. It was enclosed, kept heated, and more comfortable to swim in. I was never what you might call sports minded but I did particularly enjoy the riding.

Nathan:

You were going up and down the Peruvian mountains later?

McLaughlin:

Well, it did. I grew up very accustomed to riding. Riding over hills; there were some lovely rides to take there. If you know the place, there is a very abrupt ridge rising behind it, called "Pleasanton Ridge", which has a rather smooth, rolling top that gradually descends to the south, oh, in about four miles, down to Sunol. It made a lovely ride from Sunol to the top of the ridge, then a rather precipitous trail down to the house, about a thousand feet below. It's a nice walk today from Sunol up the ridge. You can walk for four or five miles in high country that is still empty, It's private cattle land, but I've never been put off. I've done it a few times with my daughter, Jean.

Nathan:

Oh, yes. This is her picture?

McLaughlin:

Yes. She ought to be turning up very soon. She's a senior at Anna Head now but taking, in advanced placement, some courses on the campus. [U. C. Berkeley] She took a junior course last term--got an A in it too, a French course, and now she's taking two other courses on the campus. She's finishing an 8 o'clock and should be home pretty soon. Sylvia is away today, so I have the job of taking her to school. [Laughter] I think she's already admitted to Berkeley, but she hasn't made up her mind just what she wants to do. [Jean was later admitted to Stanford, but when Princeton accepted her application she decided to go there, both on account of the strong department of music in the University and the New School for Music nearby where she could continue her work on the piano.]

Nathan:

To return to the Hearsts for a moment, did you get to know William Randolph Hearst at all?

McLaughlin:

Oh, yes. I knew him very well. He was a very good friend. I had little to do with him, however, in a business way. The Hearsts' stock in the Homestake Mining Company had been sold shortly after his mother's death so we had no association in that connection, though I was involved with him in the San Luis Mining Company and other properties that he controlled in Mexico. I had never had any connection with the newspapers or the magazines.

We're getting ahead of the story, but after he had inherited practically the whole of his mother's estate, most of the holdings in the mining companies that George Hearst had founded were sold with the exception of certain properties in Mexico. It's rather strange that I should find myself very much later in charge of the Homestake Mining Company after the Hearsts had been out of it for many years.

Nathan:

I wonder why they divested themselves of the mining interests?

McLaughlin:

Probably because W. R. Hearst was much more concerned with his newspapers and other publications. He was still interested in mining, however, for he often talked to me about the mines in Mexico—but the papers were his first love. He wanted, I'm sure, all his financial strength concentrated in the newspapers and the publishing world. Of course, he made a tremendous record there!

Nathan:

Yes, and as a collector too. Did his mother start collecting early?

McLaughlin:

He probably acquired the habit from his mother on their first trips to Europe. Of course he was a much greater collector than she was. Her collections were impressive but he really went at it professionally. He had a number of agents who were buying for him. His apartment in New York and the houses at San Simeon and Wyntoon were truly museums. He had warehouses filled with magnificent things, but most of the collections were sold off when he was in a bit of financial trouble in the thirties. It's a great shame, because it probably would have been the nucleus of one of the major museums of the country--if all the works of art that he'd collected had been kept together. There is a lot still to be seen at San Simeon, but most of the large collections in storage were sold, I believe.

Nathan:

Did he have any special interests--anything that he liked in particular? The collection is so diffuse at San Simeon it's hard to tell.

McLaughlin:

Yes. There again, it's hard to say. I doubt if anyone ever knew Mr. Hearst completely. He was a very complicated and talented person of many sides, many aspects. My impression of his taste is that he was more interested in architectural details, carvings in stone and wood, furniture, ceilings, candelabra and things of that sort, than he was in paintings. I don't think he ever had what might have been the nucleus of a great collection of paintings. He had many fine tapestries, some of which he inherited from his mother. He had a great feeling for medieval art that is revealed in the tapestries, the choir stalls, and the fine beds and furniture at San Simeon. It's really marvelous that way. Some contemporary things, of course were put in for comfort, which were nice to use, but did give the somewhat diffused feeling you mentioned.

Nathan:

Grandeur is a little difficult to live with.

McLaughlin:

Yes [laughter] but I always enjoyed it when I was visiting there.

I think I've slept in the Richelieu bed a number of times [laughter] without any ill effects! [Laughter]

Nathan:

How would you characterize Mrs. Hearst? The few biographies are so saccharine.

McLaughlin:

You are right. They're not good.

Nathan:

Annie Laurie’s, for example.

McLaughlin:

Oh, that was a horrible book. I have a copy of it up here. She didn't know Mrs. Hearst very well, I really don't ever remember seeing her down at Pleasanton, though I suppose she may have been there. I don't seem to remember many of the people who were there casually, except those who for one reason or another impressed me particularly.

Nathan:

I want to ask you about them too. It's not possible that a woman who accomplished as much as Mrs. Hearst did could have been a little spun sugar character.

McLaughlin:

No, she wasn't. She was a very dynamic, forthright little person, with very positive ideas. The life at the Hacienda was strangely formal and stiff in lots of ways. Never bothered me--I was doing just exactly what I wanted to do at that age. It seems strange now, riding horseback and swimming, and enjoying the luxury and the good things -- including the library—it seemed to satisfy me rather completely. I really didn't mind the formality in the least. Perhaps it is a sad commentary on my character that I accepted it all with out worrying about its social implications that might seem disturbing to my contemporary liberal friends. But, the good things of life were there to be enjoyed — and I accepted them gratefully and uncritically and really had a happy time, without worrying too much whether or not I deserved it.

Nathan:

The life sounds delightful. When you say that it was formal, do you mean that the table service was formal?

McLaughlin:

Oh yes. We always dressed for dinner. Even when there were only a few, perhaps no more than six at the table. Everything was very correct in the Victorian way. The dinners, in spite of their length, were entertaining because there were usually so many interesting people there that the talk was good - as well as the food. [Henry] Morse Stephens was a frequent guest. And other people from the Berkeley faculty were often invited. The Benjamin Ide Wheelers were there frequently, and it was a lively, interesting atmosphere. Cocktails were served only when it was a largish party, but not to the younger members. Three or even four excellent wines were generally served when it was a special occasion. It was all very strict, however, and I don't think anybody would ever be invited again if he— or particularly she— had one too many! [Laughter]

Nathan:

Well, she had her own standards, I'm sure. Did you have footmen behind each chair?

McLaughlin:

Oh, no I It wasn't as royal as that! But there were generally at least two butlers.

Nathan:

It wasn't country living?

McLaughlin:

It wasn't country living in the western American sense, but it had its country aspects with horseback riding and hiking in the hills. I remember with embarrassment one time at a rather formal luncheon in the big dining room—there were nearly always 20 people or 25 over the weekends--! felt something on my neck and flipped a wood- tick out on a serving plate! [Laughter] So it was a combination of country living as well, but — [laughter] after all, you couldn't escape woodticks and things of that sort in California in those days .

You were asking about Mrs. Hearst's own character. She must have been a very forceful person on the Regents, because I remember looking over some of the old minutes and seeing how President Wheeler would say, "Well, we must consult Mrs. Hearst about this." Or, "This would be subject to Mrs. Hearst's approval." So I rather imagine that she was a fairly dominant little lady on the Board. She was gentle, but by no means saccharine. She really was a very strict person, and everyone in her family had to follow a certain code of behavior that—well it seemed a normal code at the time, but it wouldn't fit in today very well! [Laughter]

Nathan:

Her son slipped the leash a bit, of course.

McLaughlin:

Oh, yes, and perhaps that was...

Nathan:

Part of it?

McLaughlin:

Family rebellions took place even in those days, but in her own house, there was no sign of it. There were a few other boys down there. One was Randolph Apperson, who died four or five years ago. He was her nephew. It's his son, Bill Apperson, now who's involved in this controversy with the Sierra Club about Apperson Ridge. Elbert Apperson, his {Randolph's] father, was Phoebe Hearst's brother. He lived at Sunol; the old house is still standing—a large wooden mansion with twelve foot ceilings, a cupola, wide porches and a lot of gingerbread. He had a ranch south of the Sunol Valley in the high country beyond San Antonio Creek which included what is now called Apperson Ridge; his grandson who owns it now is anxious to sell it to Utah Construction who want it as a source of basalt--hard rock useful for a number of purposes including Bay fill, which brings them into conflict with my wife Sylvia and the Save-the-Bay Association.

Nathan:

Yes. Do you have any views about this, just as a side issue?

McLaughlin:

I do think that a large quarry there would be an awful eyesore, right at the edge of the Sunol Park. We do, however, have to get crushed rock from some source to meet the demands of our growing population for roads and structures. I don't feel as deeply as my wife does on this, for she is an ardent conservationist, but I would be sorry to see this lovely country turned into a quarry. The rock should be found some other place. At that, however, it would not be as bad as the Kaiser quarries, right here in the Berkeley hills, where they've made a hideous scar on a particularly fine ridge between Tilden Park and Round Top-- just south of the Tunnel Road.

Nathan:

Yes, this really is one of the complicated problems of the time, isn't it?

McLaughlin:

Yes. There's not a great deal of good rock around here—crushed rock for all sorts of construction, concrete and things of that sort. But I'd be best pleased if they didn't put a quarry down there! [ Laughter]

Nathan:

I quite sympathize. If we may turn back to Mrs. Hearst again, were there other young people in Mrs. Hearst's household--including a niece or a young girl?

McLaughlin:

Yes, a good many--children or grandchildren of relatives or of old friends. One of them was a young fellow--William W. Murray—who was a cousin of Millicent Hearst—Mrs. William Randolph Hearst. He was a New York boy who came out here and Mrs. Hearst in her usual way of liking to help young boys, put him through college in Berkeley. He lived with us for several years while he was in college. After that, he held various positions in the San Francisco office of the Hearst estate for the rest of his active life. He was in charge there when he retired a few years ago. He lives over on Broadway Terrace in Oakland.

Other contemporaries of mine were Edward Clark, Jr. and Helen Clark. They were the son and daughter of Edward H. Clark, who became manager of Mrs. Hearst's affairs after the death of the Senator. They lived in New York, but spent most of their summers at the Hacienda or at Wyntoon on the McCloud River. They were both very close friends of mine. Helen, who married Howard Park during the war, died a few years ago. Eddy Clark, Jr., who later was a lieutenant with me in the 63rd Infantry in World War I, is living in San Francisco now. After graduating from Yale, he was with the American Trust Company--now the Wells Fargo Bank—and also has a couple of entertaining books to his credit.

Nathan:

In one of the books there was a reference also to a young cousin, I think, of Mrs. Hearsts's.

McLaughlin:

That was probably Edward Clark, Sr. In addition to managing the Hearst Estate for many years, he also became president of both the Homestake Mining Company and the Cerro de Pasco Copper Corporation for a time.

Nathan:

And then was there also a young woman?

McLaughlin:

Oh yes, I seem to be forgetting them. There were two attractive young women down there, older than I, next generation up; 10 to 15 years older: a niece, Ann Apperson(Flint) and a cousin, Agnes Lane (Leonard). Agnes died several years ago. Ann Apperson married a doctor, Dr. Joseph Marshall Flint, who was then on the faculty of the San Francisco Medical School of the University of California. He eventually became a professor of surgery at the Yale Medical School. [Mrs. Flint died July 13, 1970] Another lovely girl who was often there, and was one of my very dear friends, was Harriet Bradford. She made a most interesting tape for the Phoebe Hearst Association about her life at the Hacienda. The Bancroft should have a copy. Does it?

Nathan:

No. You know, I tried to trace that and I didn't succeed.

McLaughlin:

No, I'll tell you about that later. She was the daughter of a sea captain. He was always known as Captain Bradford, a handsome old boy. She was down there a great deal as a young girl. She was about my age. I don't know how they all met--it was an old friendship in San Francisco I think. Mrs. Hearst sent her to Bryn Mawr, where she did very well. Shortly after her graduation she served as Dean of Women for a while at Stanford. She then took a law degree at the University of Chicago, and ended up in a Boston law firm. She never married. We've kept up our friendship over the years; she died about a year or so ago, and in her will she left me a portrait of Ann Apperson that she particularly treasured for they were very close friends. It's out there in the hall now. It's rather nice, but not a great portrait.

Nathan:

But what a nice, sentimental thing to do.

McLaughlin:

Yes. She was really a very wonderful person.

Nathan:

I'm so astonished at the way these names just pop out of your mind!

McLaughlin:

Well, it is funny how you recall all these things. There's a little lady up in Chico--Mrs. Vonnie Eastham— who became very much interested in Phoebe Hearst s history. She has more or less made a full time job of it.

Nathan:

I think Mr. Kantor of the Archives told me about her.

McLaughlin:

She is not a professional historian, but she's devoting a lot of time to investigating Mrs. Hearst's career and getting in touch with the people in Missouri, where Mrs. Hearst came from. They've organized a Phoebe Hearst Society there, and they have the schoolhouse, in which Phoebe Hearst taught, preserved as a relic in Missouri. She's been active in trying to accumulate records (tapes, that is) of this sort. She has a very good one from Harriet Bradford, which Harriet sent me--to be returned after I had listened to it. It now is in the hands of this lady, or of The Society. She's a very nice little person. I think Eddie Clark also made a record for her. I was asked to, but never did get around to it. Eddie married Peggy Nichols, the daughter of Bishop Nichols who was the Episcopalian bishop here. I was best man at their wedding. This was back in 1917 shortly before we were commissioned lieutenants. They're divorced now, unfortunately.

But this little lady up at Chico has been very active. She doesn't have a lot of academic credentials, and The Bancroft Library perhaps hasn't taken her as seriously as she thinks she should be taken. She wanted to work down here in the records and I am afraid they may have brushed her off a bit.

Nathan:

Did they hurt her feelings?

McLaughlin:

Maybe. Harriet Bradford, I think, sent her all her correspondence with Mrs. Hearst and Mrs. Flint. Mrs. Eastham didn't seem too enthusiastic when I suggested that the Harriet Bradford letters should go to The Bancroft Library.

Nathan:

So she has the letters! [Laughter]

McLaughlin:

I think so unless they have been sent to the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Society in Missouri. I was terribly afraid at one time that she might persuade W. R. Hearst, Jr. to let her have some letters from the files he had. But fortunately all those archives are definitely in The Bancroft and they, of course, contain the important letters. All the letters of Phoebe Hearst herself, which were stored at San Simeon, now are in The Bancroft. This little organization in Missouri—worthy as it is--is hardly the place for the documents that might become of considerable interest to California historians. But I think The Bancroft Library had better cultivate her.

Nathan:

I think you have a very good point. We'll have to tip off Bancroft, especially if she is in possession of some good letters.

McLaughlin:

Well, she has the Harriet Bradford letters. The Phoebe Hearst Society in Missouri is a little group of devoted people, but I think they are more interested in Phoebe's early years and her contribution to the Parent-Teachers Association than in her life in California.

Nathan:

That's very interesting — you have to be wary of your friends. Did you ever discuss politics at the Hacienda or hear Mrs. Hearst give her views on this sort of thing?

McLaughlin:

Yes, well, with the people who were down there. There were frequently distinguished people coming in from Washington. It was really in many ways an important center of life on the Coast, for many people of importance were invited and entertained. The [Herbert] Hoovers were there quite often. At that time, he had already become a successful and outstanding mining engineer. He must have still been in his late thirties when I met him first down there, I was just a freshman in the College of Mining. He had a great interest in young people, even then, and talked to me a lot about mining careers and how one got started. I was tremendously flattered that anybody of his distinction as a mining man would spend so much time with a youngster. Then I didn't see very much of him after those early years.

In fact I had nothing to do with his Belgian relief work and did not have any opportunity to see him during the years he was President. After he was out of the White House, however, there were quite a number of occasions when I was with him. He recalled the visits he had made to the Hacienda and even remembered me as a boy. He was always cordial and sent me copies of several of his books. He rarely missed being at the Bohemian Grove during the summer encampment and I made a point each year to call on him at his camp for he always seemed interested in talking about old mining experiences, as well as current activities in his field.

Nathan:

Was he a gold and copper man as you turned out to be?

McLaughlin:

He was into pretty nearly everything. On one of his early jobs in Australia, in Western Australia, he had charge of a mine called the "Sons of Gwalia" which was a successful gold mine. When I was in Western Australia in 1935, I happened to ask an old timer if he had known Mr. Hoover. He replied: "Oh, yes, but I thought he was a bit of a wowser, you know." It didn't quite seem in character to me until I learned the "wowser" in Australian slang was a type that avoided the pubs on Saturday night.

Hoover was associated with a London group that was concerned with development and operation of a wide range of mines. His activities with them and other connections took him all over the world. That led to his being in England in 1914 when the war broke out. He played a big part in getting the Americans home who were stranded without ready funds. That was really his first war activity. Soon after, he organized the Committee for the Relief of Belgium, which functioned under his direction until we went into the war when he became food administrator for President Wilson. That's the way he left mining.

Nathan:

How did you determine that you were going to Cal, to the University at Berkeley?

McLaughlin:

Well, living in Berkeley and spending a good part of my time as I did at the Hacienda in Phoebe Hearst's household, I heard a lot about the University. It became a very clear objective to me to meet its requirements and enroll as a student. Indeed, at the time, I doubt if I considered any other alternative, except to go to college in Berkeley. Mining was, of course, very much in the background at the Hacienda. In those days the manager (who was then called the Superintendent) of the Homestake Mine was T. J. Grier. He and his family often visited at the Hacienda. I became very good friends with all of them. I did go up to Lead in the Black Hills in one of my summer vacations, and worked in the cyanide plant for a while. Previous to that I had worked for part of the summer of 1912 in the Central Cyanide Plant of the North Star Mine which was then one of the major mines in the Grass Valley district (California), In those days, Grass Valley and Nevada City nearby were primarily mining towns — quaint perhaps in retrospect, but then a bit primitive. The Holbrooke House was the only hotel, but I soon found a pleasant room in a private house. Bathing facilities were limited, but that seemed unimportant then. There were some good parties at the Footes — he was manager of the North Star and in the Bourne mansion — and at the Starrs at the Empire Mine, which was then in its most prosperous period. All in all, my memory of the summer there is decidedly pleasant. It's a fragrant country with pine and oaks of the lower forest zone of the Sierra Nevada and a distinctive country of red soil, canyons and streams that one never forgets. And I can still smell the strange, rather subtle odor of the cyanide plant. So that more or less started my interest — though I am afraid it turned me away from metallurgy and toward geology.

Mrs. Hearst had given the University the mining building, which is still one of the best pieces of architecture on the campus. I knew Dean S. B. Christy well and mining seemed a good field to go into. Mining engineering was quite a glamorous profession in those days . It is much less popular now and as a separate curriculum it has practically died on the vine in the University and in most other places as well. But in those days, it was one of the glamour fields, and it seemed rather a natural thing to go into. Especially in the handsome new Hearst building. So that's the way I started in mining. Though of course even in the mining curriculum, as it was in those days, the first three years were mostly devoted to mathematics, physics, chemistry, geology and general engineering. The mining aspects of it you really didn't get into until your senior year.

By that time I had rather drifted away from the mining engineer ing and into geology. I took some courses under Andy Lawson [Andrew C. Lawson], who was a great teacher, and George Louderback, so I think my interests rather strayed from mining as it was taught then. As I said, [Samuel B.] Christy was Dean, and quite an extraordinary old boy, but it seemed to me that my future was not in the things he was teaching, but in the utilization of geology in the search for ore.

Nathan:

Did you have an idea that you were going to be interested in geology or mining when you went to the University as an undergraduate?

McLaughlin:

I had an idea that I would be interested in mining, but that probably was influenced by some of the people I saw at Phoebe Hearst's house and by the fact that her fortune — and very delightful way of life — had been made possible by the success George Hearst had in mining. I had seen some of the operations that were the base of that for tune. And then with the construction of the fine new mining build ing it seemed rather an appropriate thing to go into that field. Furthermore, exploration, particularly in mountainous country, had always excited me and geology and the search for new mineral deposits offered a pattern of work that fitted in very well with my early enthusiasms.

McLaughlin:

My interest in geology came in the course of my undergraduate work in Berkeley. I rather drifted away from what was called mining engineering as it was taught in those days, a good deal of which was really trade-school stuff, and into geology. I debated for a while whether or not I would go into chemistry or geology in my junior year, but I finished the mining curriculum, though I did as much work as I could in geology. When I went on to graduate work in geology at Harvard, I found that my engineering training was very good preparation, for it had provided me with the mathematics, physics and chemistry I needed for advanced work.

Nathan:

Were there any professors on this campus that you remember as being influential or exciting to you?

McLaughlin:

I remember in the engineering field taking theoretical mechanics with Professor LeConte, the son of the geologist, generally called, "Little Joe." [Laughter] He was a very good teacher, and it was a very good course. I think he was one of the outstanding teachers I had. In mathematics I had the good luck to have Baldwin M. Woods as my instructor in the calculus. As you know, he later became a vice- president and my friendship with him was renewed when I returned as a dean and later as a Regent.

Nathan:

What was it that Little Joe LeConte taught you?

McLaughlin:

Theoretical mechanics.

Nathan:

Have these areas changed over the years or are these the conventional courses?

McLaughlin:

Many changes in emphasis but there's a lot of basic material that stays the same. The methods of teaching, the manner of presenting even some of the rather static concepts have changed a lot, however.

Nathan:

Were there colleagues or fellow students who were memorable to you?

McLaughlin:

Yes. There were several boys in the class who became very successful in mining work, though I haven't seen many of them. One of them was Jack Abrams , who was a football man too. He became manager of the great Climax Molybdenum Mine in Colorado and made a fine record in mining. He died some years ago. I should say as a mine operator he had the most distinguished record in the class. He went into straight mining, really did a great job.

Nathan:

About how large were the classes?

McLaughlin:

Oh, quite small. I think the graduating senior class in mining engineer ing wasn't more than 25 or 30. The old-fashioned education in mining engineering was already beginning to decline even then. It was a fascinating field at one time for it was linked with exploration and development of new properties all around the world. Hoover was the type of man who had risen to success in it, and Berkeley graduates like Will Mein, Charles Merrill, Ed Oliver and Butters, who were metallurgists and inventors. We have a brilliant lot of mining engineers and managers among our alumni though we can't claim Hoover. Gardner Williams, who developed the Kimberly diamond mines in South Africa was one of them and another was Stanly Easton who for years ran the big Bunker Hill and Sullivan Company in the Coeur d'Alene district in Idaho. Members of the Bradley family and Stuart Rawlings were among those who had distinguished careers in mining and all were graduates in mining engineering. Mining was a very glamorous field then.

McLaughlin:

But gradually as engineering became more and more technical, more and more exacting, the old mining curriculum almost seemed to have become something of a trade-school type of training and it just withered away. It was a separate college, you know, until 1942, separate from the College of Engineering. When Bob Sproul persuaded me to leave Harvard and come here in 1941 after Dean Probert's death—he was Dean of the College of Mining—the plan was to put the courses of the College of Mining into the College of Engineering and continue then as a Department. The understanding was that I would be Dean of Engineering and Chairman of the Department, which I did become.

There was so much sentiment about the Mining College on the part of old graduates that there was a lot of opposition to merging it with Engineering, but it was the right thing to do. Enrollment had declined seriously and now mining engineering— in name at least- has disappeared even as a department. That's true today in most other universities too. So many had mining colleges at one time. It isn't that the mining industry has declined— it 's greater than ever, far greater than ever—but it draws from all other fields of engineering, plus geology.

Nathan:

Does it require more specialized teams?

McLaughlin:

In a sense, less attention to some of the old, so-called practical things that can be learned better in the field than in the university. It needs men with broader basic knowledge as well as more exacting training in some specialized fields. A great many people now go into mining through geology. You can prepare for a career in mining through mechanical engineering, or go into jobs in the mining industry through civil engineering. There's been a vast change in the approach toward training men for the field.

Nathan:

Sounds much more sophisticated.

McLaughlin:

Oh, it is. Much more. It doesn't mean we're not in great need of skilled professionals. We don't need fewer, now we need many more very ably trained engineers for the mining industry than ever before, but it's not confined to men with the old, restricted mining school type of education.

Nathan:

Does it require a broader theoretical background?

McLaughlin: