Milestones:First Blind Takeoff, Flight and Landing, 1929

- Date Dedicated

- 2014/09/24

- Dedication #

- 145

- Location

- Garden City, NY, U.S.A.

- IEEE Regions

- 1

- IEEE sections

- Long Island

- Achievement date range

- 1929

Title

First Blind Takeoff, Flight and Landing, 1929

Citation

On 24 September 1929, the first blind takeoff, flight and landing occurred at Mitchel Field, Garden City, NY in a Consolidated NY-2 biplane piloted by Lt. James Doolittle. Equipped with specially designed radio and aeronautical instrumentation, it represented the cooperative efforts of many organizations, mainly the Guggenheim Fund’s Full Flight Laboratory, U.S. Army Air Corps, U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Sperry Gyroscope Company, Kollsman Instrument Company and Radio Frequency Laboratories.

Street address(es) and GPS coordinates of the Milestone Plaque Sites

, Cradle of Aviation Museum, 1 Charles Lindberg Blvd., Garden City, NY 11530; Latitude 40.728077’ N, Longitude -73.597389’ W.

Details of the physical location of the plaque

The plaque will be securely mounted in the museum on the wall of the Mitchel Field Flight Safety Exhibit.

How the plaque site is protected/secured

The plaque will be located inside the museum. The museum is protected by security personnel during visitor hours when it is open and by an alarm system when it is closed. The museum is open daily during the summer and from Tuesday to Sunday the rest of the year.

Historical significance of the work

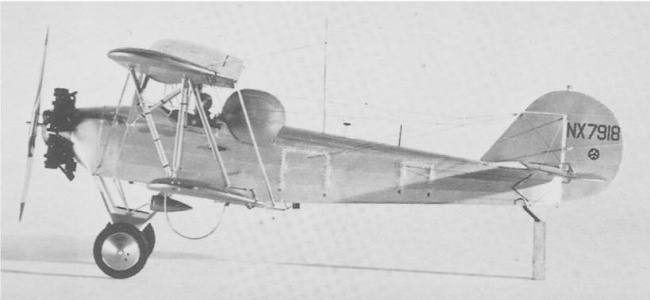

After World War I the role of aviation expanded from primarily the military to commercial enterprises with mail, cargo and passenger flights. Weather and visibility could disrupt regular flights which were required for the new aviation industry to be commercially successful and for the Post Office to establish overnight delivery schedules. During the 1920s there was slow but steady progress in the development of cockpit instruments to assist pilots flying during conditions of low visibility. At the beginning of the decade, the instruments which were primarily mechanical, could provide altitude, attitude, direction and air speed information, but not an aircraft’s spatial position, which was crucial during landing. Instruments and navigation aids were needed which would allow an aircraft to be flown on a course in fog, in any condition of visibility or no visibility. The first blind flight occurred on September 24, 1929 when U.S. Army Air Corps pilot, Lt. James Doolittle*, at the Guggenheim’s Full Flight Laboratory at Mitchel Field (Figure 1), took off in a specially instrumented Army Air Corp NY-2 Husky aircraft (Figure 2a) built by the Consolidated Aircraft Corporation with Lt. Benjamin Kelsey** as his safety officer and landed after a fifteen minute, 20 mile, flight without ever seeing the ground. At the time the NY-2 Husky was the world’s most instrumented aircraft engaged in blind flying research. The rear cockpit contained the blind flying displays and during the trials preceding the blind flight was covered by a special hood to eliminate external references (Figure 2b.)***

In Doolittle’s own words, “We both got into the plane, and the hood over my cockpit was tightly closed. I taxied out and took off toward the west in a gradual climb. At about 1,000 feet, I leveled off and made a 180-degree turn to the left, flew several miles, then made another left turn. The airplane was now properly lined up on the west leg of the Mitchel range, so I started a gradual descent, I leveled off at 200 feet and flew level until I passed the fan marker on the east end of the field. From this point I flew the plane down to the ground using the instrument landing procedure we had developed. The whole flight lasted only 15 minutes. So far as I know, this was the first time an airplane had taken off, flown over a set course, and landed by instruments alone.”

Crucial to the success of the flight, in addition to the newly developed Kollsman Altimeter and the Sperry Directional Gyro and Artificial Horizon, was the radio range and marker beacon developed by the Bureau of Standards and the special radio receiver with a vibrating reed display built by the Radio Frequency Laboratories. The special instrumentation installed on the NY-2 also included a radio transmitter and receiver with a trailing wire antenna that provided voice communications. At the time the standard installation utilized only Morse code transmitters and receivers which made their use problematic under difficult flying conditions. A unique application of the radio on the NY-2 was its use to synchronize the Kollsman Altimeter with the ground barometer reading. The cockpit (Figure 3) was outfitted with a number of the standard cockpit instrument displays of the time as well as the special ones developed by the Sperry Gyroscope Company, the Kollsman Instrument Company and the Radio Frequency Laboratories. Among them were the: Kollsman Altimeter (#1, upper right in Figure 3), Standard Altimeter, Magnetic Compass, Air Speed Indicator, Sperry Artificial Horizon (#2, first row left in Figure3), Turn & Bank Indicator, Rate of Climb Meter, Tachometer, Chronometer, Earth Inductor Compass, Oil Pressure, Oil Temperature, Ammeter, Voltmeter and the Vibrating Reed Localizer Display (#3, lower left in Figure 3). The NY Times which reported the flight in detail stated that only three specially designed instruments had been installed and included a photo of the cockpit instrument panel identifying each of the instruments. The Sperry Directional Gyro was not among those identified. In the 1930 Vol. 6, No. 2 issue of, “The Sperryscope,” an article about the newly developed gyroscope-based instruments for aircraft states that both the Artificial Horizon and the Directional Gyro were installed in Doolittle’s plane. Richard Hallion in his book, Legacy of Flight, also states that a Gyrocompass (Directional Gyro) was installed in the plane, but the cockpit instrument panel shown in his book has a somewhat different layout from that in the NY Times photograph. During the test flights preceding the blind flight, different instrument configurations had been tried. A photo in the Guggenheim report, Equipment Used in Experiments to Solve the Problem of Fog Flying, shows the Blind Flight Laboratory’s final cockpit instrument panel with the Sperry Directional Gyro but does not include the vibrating reed display.

When James Doolittle was selected to head the Full Flight Laboratory, he was officially “borrowed” from the Air Corps for a one year period of detached service and had received in 1926 his doctorate in aeronautical engineering from M.I.T. During World War II he volunteered for and received General H.H. Arnold's approval to lead the top-secret attack of 16 B-25 medium bombers from the aircraft carrier USS Hornet on April 18th in 1942, with targets in Tokyo, Kobe, Yokohama, Osaka, and Nagoya. The success of the raid was a big morale booster for the United States in the aftermath of successive victories by the Axis during the immediate months after the beginning of the war.

Benjamin Kelsey graduated M.I.T. with a BS in June 1928, and stayed to teach and conduct research work in the aeronautics department. He flew for commercial concerns as well as privately obtaining a transport pilot’s license. He joined the United States Army Air Corps and was commissioned a second lieutenant on May 2, 1929. He was assigned to the Full Flight Laboratory at Doolittle’s request and at Harry Guggenheim’s insistence flew as Doolittle’s safety pilot during the NY-2 Husky instrument flights. During the first 'blind' instrument flight on September 24, 1929, he showed observers that he was not in control by keeping his hands visible outside the cockpit. For a film clip from the Getty Archives showing Lt. Kelsey and Lt. Doolittle in the NY-2 Husky with Lt. Doolittle pulling the hood over the front cockpit and describing the contributions of the Sperry Artificial Horizon and Directional Gyro, click on http://www.gettyimages.com/detail/video/james-jimmy-doolittle-performs-first-blind-flight-news-footage/145012946. Note that on the model of the plane shown in the preceding photograph the hood is shown on the rear cockpit.

Features that set this work apart from similar achievements

The achievement of the first blind flight and landing was the result of an unusual cooperative effort primarily involving the Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics, the U.S. Army Air Corps, the Department of Commerce, the Sperry Gyroscope Company, the Kollsman Instrument Company and the Radio Frequency Laboratories. Other companies, the Pioneer Instrument Company, the Taylor Instrument Company and the Bell telephone Laboratories contributed as well. Doolittle’s successful blind flight and landing demonstrated that having and being able to use accurate and reliable instruments was the key to safe flying, under near zero visibility conditions and that contrary to the belief of many pilots at the time that being able to fly, “by the seat of my pants,” was the more important skill. Of all the organizations that contributed to the success of Doolittle’s flight, were it not for the Full Flight Laboratory established by the Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics, Doolittle’s achievement that helped pave the subsequent rapid growth of the aviation industry might well not have occurred until several years in the future. Furthermore, it paved the way to the all weather microwave landing systems that are currently used.

Significant references

NOTE: Extensive use was made of the Cradle of Aviation Museum’s library of original material and its collection of aviation related photographs.

- J. H. Dellinger, H. Diamond and F. W. Dunmore, Development of the Visual-Type Airway Radio-Beacon, Proc. of the I.R.E., Vol. 18, May 1930.

- H. Diamond and F. W. Dunmore, Development of the Visual-Type Airway Radiobeacon System, Proc. Of the I.R.E., Vol. 19, April 1931.

- H. Diamond and F. G. Kear, A 12-Course Radio Range for Guiding Aircraft with Tuned Reed Visual Indication, Bu. of Stds. Journal of Research, Vol. 4, September 18, 1929.

- R. P. Hallion, Rhythms of Speed and Streamlining, the Transformation of American Aviation, 1935: The Reality and the Promise Conference, April 7-9, 2011, Hofstra Univ., Hempstead, NY.

- Blind Plane Flies 15 Miles and Lands; Fog Peril Overcome, The New York Times, p.1., September 25, 1929.

- G. E. White, Tubes, Transistors and Takeovers, Avionics, Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow, June, 1984.

- E. M. Conway, Blind Landings, The John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD., 2006

- General J. H. Doolittle with Carroll V. Glines, I Could Never be so Lucky Again, Bantam Books, NY, 1991.

- Daniel Guggenheim Fund, The Final Report of the Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics 1929, September 1930.

- McCormick, B.W., Newberry, C.F., Jumper, E., Aerospace Engineering Education During the First Century of Flight, A.I.A.A., June 30, 2004.

- White, G.E., Tubes, Transistors and Takeovers, AOPA Pilot, June, 1984.

- Irwin Unger and Debi Unger, The Guggenheims, HarperCollins Publishers, NY, 2005.

- Leary, William, The Search for an Instrument Landing System, 1918, Innovation and the Development of Flight, edited by Launis, Roger, Texas A&M University Press, 1999.

- New Radio Beacon can Sift Course from Among 12:Device Perfected by Bureau of Standards, New York Times, Aug. 18, 1929.

- Whitaker, O. B., “New Gyroscopic Instrument Contributes to Safe Flying,” The Sperryscope, Vol. 6, No.2, Sperry Gyroscope Company, 1930.

- Hallion, Richard, Legacy of Flight, University of Washington Press, Seattle, 1977.

- Helfrick, Albert, Electronics in the Evolution of Flight, Texas A&M University Press, 2004.

- Equipment Used in Experiments to Solve the Problem of Fog Flying, The Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics, Inc., New York City, March 1930.

Supporting materials

NOTE: The photographs used in the proposal have either been obtained from the Cradle of Aviation Museum's photo archives with permission or other public sources without indicated permission requirements.

Map