Milestones:Decew Falls Hydro-Electric Plant, 1898

Decew Falls Hydro-Electric Plant, 1898

St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada, Dedication: 2 May 2004, IEEE Hamilton Section

The Decew Falls Hydro-Electric Development was a pioneering project in the generation and transmission of electrical energy at higher voltages and at greater distances in Canada. On 25 August 1898 this station transmitted power at 22,500 Volts, 66 2/3 Hz, two-phase, a distance of 56 km to Hamilton, Ontario. Using the higher voltage permitted efficient transmission over that distance.

The plaque can be viewed at the Decew Falls Generating Plant No. 1, 6.4 km south of St. Catharines, Ontario: 15 Lockhart Drive, St. Catharines, Ontario

DeCew Falls No. 1 Plant

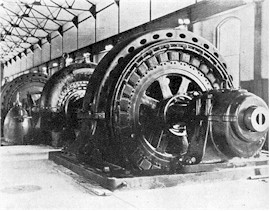

The first plant at DeCew Falls , two miles from St. Catharines, was built by the Cataract Power Company to supply power to Hamilton, a distance of 35 miles. It draws water from Lake Erie through the Welland Canal, with a storage reservoir in Lake Gibson. Seven steel penstocks are supported on the hillside by concrete piers. The direct-connected, turbo-generator units are mounted horizontally on a gravel foundation. The tail-water is carried downstream in Twelve Mile Creek to Lake Ontario at Port Dalhousie. The head is 260 feet. This plant began operation with two 1,500-hp units on 26 August 1898; two 3,000-hp units were added in 1900; the plant was completed in 1912 with a total output of 44,600 KVA at 66 2/3 cycles. It supplied power to Hamilton several years before Niagara power reached Toronto. In 1930 it was bought by Ontario Hydro and converted to 60 cycles. This is the oldest Niagara plant still operating.

The Cataract Power Company of Hamilton Limited (the predecessor to the Dominion Power and Transmission Company) was organized in 1896. The idea for the company came from John Patterson (one of the "Five Johns" to found the Cataract Power Company) who was developing the Hamilton Radial Electric Railway at the time. He wanted to supply his railway with water-generated electric power and selected De Cew falls as the place to do this. The water originated mostly from the Welland Canal and was used to supply St. Catharines. Before the project could commence, the waterworks commission of St. Catharines had to be consulted. Though they were initially supportive, in the end they refused to provide the necessary facilities. Subsequently, engineers were called on to devise a way to divert the water from the Welland Canal to a more suitable site. They recommended building a waterway to the escarpment bordering the canal channel. In 1897 the Cataract Power Company got a lease for water from the Welland Canal at Allanburg. A canal was constructed from Allanburg to an area near the falls which had recently been converted into an 800-acre storage dam. This in turn led to the power house at the head of the falls. Known as the "Power Glen" plant, it transmitted electricity along 34 miles of wire to the city of Hamilton.

At the time long-distance transmission of electric power was still being developed. Lord Kelvin, an English authority on electricity, stated that electric power could not be transmitted further than 12 miles economically. With the development of new types of equipment however, in 1898 electric power was successfully delivered almost three times that distance at a voltage of 22,500 volts (more than double any previously used voltage). Following the establishment of this local source of electric power, many of the radial railways switched from steam to electricity.

Though the "Power Glen" had one penstock operating two units with a capacity of 9,000 horse power at the outset, this would expand in the following years to seven units with a capacity of 52,000 horse power, making it one of the most economical installations in North America. This allowed the company to provide attractive prices and make enough profit to acquire the radial electric railways centered in Hamilton as well as the power services of Hamilton and Brantford (among others). The first of these was the Hamilton Electric Light and Power Company, which had closed its steam plant and had begun purchasing power from the Cataract Power Company.

In 1899, the Hamilton Electric Light and Power Company was taken over by the Cataract Power Company, which subsequently changed its name to the Hamilton Electric Light and Cataract Power Company Limited. In 1900, the newly named company bought both the Hamilton Street Railway and the Hamilton Radial Electric Railway. A further name change occurred in 1903. The company was incorporated as the Hamilton Cataract Power, Light and Traction Company Limited. This name would not last because in 1907 the company was organized for the last time as the Dominion Power and Transmission Company (D.P.&T.). This all-encompassing name reflected the company's large list of subsidiaries (of which there were 12).

As the company expanded smaller hydraulic plants were built in Brantford and St. Catharines and steam plants were built in Brantford and Hamilton. The Hamilton steam plant, constructed in 1917, was the largest of the four new plants with a capacity of 23,000 horse power.

Even though Dominion Power and Transmission (DP&T) was expanding it still encountered difficulties. D.P.&T. had encouraged the belief that they were operating in the best interests of Hamilton and that they were more akin to a public service organization than a business. However, the 1906 strike of one of its subsidiaries, the H.S.R., dispelled this perception as the public's resentment towards H.S.R. management was transferred to D.P.&T. Many people thought that D.P.&T. emphasized its industrial customers over its municipal ones. When the publicly-owned Hydro-Electric Power Commission was formed in 1906, many were ready to see D.P.&T.'s monopoly defeated. Although a by-law submitted to ratepayers to enable the City of Hamilton to enter into a contract with the Commission passed, D.P.&T. still had support on City Council and was able to have its contract renewed for five years. However, when asked for tenders, the Commission estimated costs for such things as arc lamps and sewage pumping at significantly lower prices than what D.P.&T. had been charging. D.P.&T. lowered their prices accordingly and made an offer to supply any municipality with service at rates ten percent lower than those of the Commission. Nevertheless, when D.P.&T.'s contract ran out in 1911 a new by-law was passed allowing the City of Hamilton to get its power from the Commission. Additionally, the city would own its own distribution system: a hydro-electric plant costing $505,160. The system was adopted in 1912 and put into operation in 1913. Even though D.P.&T. had lost its monopoly, it still retained almost all of its business and industrial customers (which had always been its primary focus).

Since its inception, D.P.&T. was greatly interested in interurban railways and their expansion, however, this area of business would prove to be unprofitable as time wore on. With the death of John Patterson (D.P.&T.'s biggest promoter of radials) in 1913 came the increasing realization that electric railways had a poor potential for profit in the face of automobiles. The last new interurban cars were purchased that year and no further improvements were made to the lines from then on. D.P.&T. still wanted a piece of the transportation pie however, and began by purchasing 10 buses in 1926. By 1929 the company was replacing its radial lines with bus lines, buying up competing bus lines and increasing its fleet of buses to ninety-two.

In 1930 the D.P.&T. company was taken over by the Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario (better known as Ontario Hydro). Ontario Hydro promptly sold the entire bus system to Highway King Coach Lines on the condition that the bus lines would be protected against interurban competition. This was the final motivation for the complete abandonment of the radials, and with them, the last traces of the Dominion Power and Transmission Company passed away.

Map