Inventors’ Responses to the Sinking of the RMS Titanic

This article was initially published in Today's Engineer on April 2012

The sinking on 14-15 April 1912 of the RMS Titanic on her maiden voyage after colliding with an iceberg stunned the world. Although Titanic was by no means the first ship to be sunk by an iceberg, the appalling loss of life (more than 1500 persons died) captured the world’s attention. The relatively new technology of radio was brought to public notice—both for its role in summoning rescue ships, and also because radio messages from the rescue ship Carpathia and from Titanic’s sister ship Olympia were listened to by radio operators on shore and relayed to the newspapers. The Titanic story became one of the first major news stories to unfold via radio.

Perhaps because technology played such important roles, both positive and negative (watertight compartments which failed to save the ship, radio ice warnings and radio distress calls which went unheeded because the nearest ship’s operator had gone off duty) and radio calls which did summon assistance, albeit from the Carpathia which had farther to steam, it is not surprising that a number of inventors responded to the sinking with new technologies of their own.

Five days after Titanic’s sinking, Lewis Fry Richardson—whose researches and experiments were driven by his Quaker beliefs, and who is most famous for his work on the causes and prevention of wars—filed a provisional application for a British patent for an “Apparatus for warning ship of its approach to large objects in fog.” Three weeks later, Richardson filed a provisional application for the underwater version. Richardson’s device depended on the sending out a beam of sound from a parabolic reflector, and listening for and timing the echoes received back from any large objects—land, icebergs, or other ships. Richardson’s patents did not lead to a working device. Practical problems, such as transmitting a satisfactory sound, and the varying absorption of sound by moisture in the air (fog) made detection of obstacles by sound difficult. In fact, experiments in 1913 by ships in the newly-formed International Ice Patrol using echoes from their whistles to detect icebergs were inconclusive.

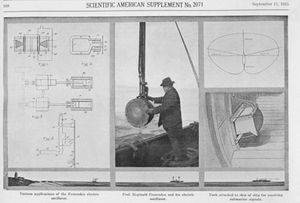

However, Canadian Radio Pioneer Reginald Fessenden, who was most famous for his success in transmitting voice by wireless, was also working on a solution. Like Richardson and many others, Fessenden had been disturbed by the Titanic’s sinking. Within two months of the disaster, Fessenden was at work on applying his high-frequency oscillator—the device which produced the continuous wave which had made his earlier wireless voice transmissions possible—to solving the problems of underwater obstructions. On 29 January 1913, Fessenden applied for a patent on an electromechanical oscillator. Because Fessenden’s oscillator was capable of sending out a signal at a fixed frequency, it was much more suitable for the task.

The Submarine Signal Company of Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.A. (acquired by Raytheon in 1947) offered Fessenden a chance to develop his apparatus. Fessenden experimented with and refined it during 1913. In 1914, a set of circumstances coalesced to provide the means (i.e. ships) that gave him an opportunity to test the device at sea.

Immediately after Titanic’s sinking, two U.S. Navy cruisers, Birmingham and Chester had been sent to the Grand Banks region of the North Atlantic for the remainder of the 1912 ice season to track icebergs and send radio warnings of their locations to ships in the region. For the 1913 ice season, they were needed in the Caribbean and so were replaced by the revenue cutters Miami (later the Tampa) and the Seneca. This new use for the Revenue Cutter Service saved the service from being disbanded. Its merger with the U.S. Life-Saving Service by act of Congress in 1915 created the U.S. Coast Guard. On 12 November 1913 the first international conference on the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) convened in London. Thirteen nations signed and agree to share the expense of an international ice patrol.

14 April 1914, the two-year anniversary of Titanic’s collision, found Reginald Fessenden aboard the U.S.R.C. Miami at the southeast corner of the Grand Banks—very near where the liner had sunk.

Fessenden’s oscillator was a spectacular success. Captain J. H. Quinan of the Miami reported that Fessenden was able to detect an iceberg at distances of two and a half miles (4 kilometers). Fessenden was also able to use his oscillator to detect the depth of the ocean (confirmed by anchor chain) as 200 feet (61 meters).

Ocean travel had just become far safer, thanks to a radio pioneer who would be remembered primarily for other inventions. In 1921, Reginald Fessenden was awarded the Institute of Radio Engineers’ Medal of Honor.