First-Hand:The Nickel Plate Gold Mine and the Bering River Coal Field

Contributed by: Robert R. Phillips, Life Member

Introduction

In the late-1940s I would go with my grandfather, Wesley P. Rodgers, on his survey jobs. I was in my teens, and he was in his 70s. He could out walk, out climb and out last me. He carried his own equipment, which was a C L Berger & Sons (Boston, MA) transit (serial number 6113). It was his “lifetime companion." Wes was well known for his surveying, which was done with great precision. Every night he would go to his office and record his survey work for the day by lantern light, since the farm did not have any electricity. If the survey work was not correct, he would go over it again the next day. During the time I spent with him, he would relate stories from his early days that he spent in British Columbia and Alaska as a civil engineer and surveyor.

Wesley Parker Rodgers was born on 4 April 1874 in Charleroi, Pennsylvania and known as Wes. He also attended Washington and Jefferson College as did other of his siblings. He graduated from there in 1898 as a civil engineer, but during his youth he learned farming from his father who had a dairy farm. During his college years he pitched on the W and J baseball team and became famous for his “fadeaway” pitch. After he graduated from college he was slated to try out for the Pittsburgh Pirates, but before he could his brother Myron asked Wes to join him in Hedley, British Columbia to help him design and build the Nickel Plate Gold Mine there. Wes moved to Hedley in 1898 where he remained for about seven years. During this time he went to Chicago in 1900 and took further courses in geology and mineralogy at North Western University and a course in assaying at the Chicago School of Assaying. He played on the Hedley baseball team and was their star pitcher. It appears that his “fadeaway” pitch was still working. When Wes left Hedley the baseball team suffered, and his absence was much lamented in the Hedley Gazette, since by all accounts he was a wonderful pitcher.

Myron Knox Rodgers was born on 6 November 1861 in Charleroi, Pennsylvania. He also was a graduate of Washington and Jefferson College, and about 1891 he went to Helene, Montana where he secured a position as a rod-man on a locating engineering party of James J. Hill. Mr. Hill was the builder of the Great Northern System that extended from St. Paul, Minnesota, to Seattle, Washington. A short time later he was promoted to transit-man of the party, and then to chief of party. Myron Rodgers soon came to the attention of Mr. Marcus Daly, who owned what was to be known as the great Anaconda Copper Mine. Mr. Daly sent Myron around the world looking for other mineral deposits.

One of his important discoveries was the Nickel Plate Gold Mine at Hedley in South Central British Columbia, Canada (49°21'28.14"N - 120°04'33.11"W). In the fall of 1898 he was going along a street in Vancouver, B.C., and noticed in a store window a few samples of ore. This ore showed a remarkable character, and he asked about its origin. It was from a location that was 150 miles from the end of the railroad, seventy miles were over a lake, forty by wagon road and forty more over mountain trails. He went and examined the prospect at once and the samples he brought out with him assayed high in gold. He then made a second trip to check his former results. In order to obscure his travels he went there from another direction, almost opposite of his former trip. After the property proved very satisfactory, Mr. Daly gave Myron the funds to build the facilities required to put the mine in operation. When the plant was ready more than $850,000 had been expended. Mr. Daly died in 1902, and Myron Rodgers left the mine and went on to discover the great Granby Copper Mine in Northern British Columbia. Wesley Rodgers went back home to Charleroi and was married in 1905.

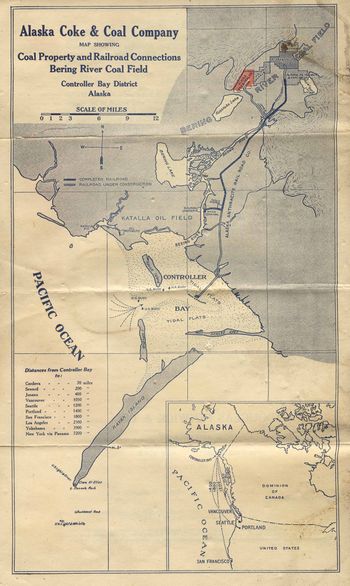

Map of locations where Wesley Rodgers worked described in this paper.

In 1905, Myron Rodgers had been in New York City and was hired by the Guggenheim family to take care of their northern explorations in Alaska, namely the Bering River coal field. Myron once again hired his brother Wes to assist him, and they both moved their families to Seattle, Washington. This second phase of Wes' life began surveying the Bering River coal field near Katalla, Alaska (60°11'42.03"N - 144°31'16.02"W) and building a railroad into it. Wes estimated that he was in all but three of the states and all the providences of Canada but two. In his travels he crossed the continent about 44 times (mostly by train).

During my time with my grandfather, he would tell me stories of his life in British Columbia and Alaska. They were stories about train robbers, Kodiak bears, and living in 40 degrees below zero weather. As a teenage these were wonderful, but I never wrote them down. As the years went by, I realized what I had lost and wished that I had preserved his stories for my children. About fives years ago one of my cousins, sent me a package. It contained seven of my grandfather's great stories that he had written near the end of his life. He was 84 years old at the time, and still surveying. Wes quit surveying at the age of 94 in 1968 and lived on the family farm being cared for by his sisters and friends. On 26 April 1970, 22 days after his he 96th birthday, he went out for his usual morning walk and never returned. They found him on his rounds dead from a stroke.

The stories have allowed me to put together much of the early history of his work at the Nickel Pate and Bering River coal field projects. The history of the Nickel Plate mine is well documented (https://www.hedleymuseum.ca/); so I will not repeat this work, but provide some of Wes' personal history. However, little is known about the Bering River coal field work, in particular the construction of several railroads. The City of Cordova (https://www.cityofcordova.net/) has been trying to reconstruct this part of its history and recover the only remaining object from it. It is a 0-4-0 tank locomotive known as "Ole" on an abandoned piece of track near the Bering River. Like "Ole" these "First Hand" stories are dedicated to the hundreds of people who labored in this coastal part of Alaska to build the facilities to mine its minerals in the early 1900s.

I have divided the "First Hand" stories of Wes into a section on the Nickel Plate Gold Mine and his other stories into the Bering River Coal Field section. I have kept his stories unedited just as he typed them on his old typewriter with his wording and expressions of the time. I can hear him tell me these stories and more as we walked the fields near Charleroi, PA.

The Nickel Plate Mine

Wesley Rodgers moved to Hedley in 1898 where he remained for about five years. Wes wrote several stories about his life there that include a run-in with some train robbers in 1904 that are still part the folklore of that area. He also played on the Hedley baseball team.

There appears to be at least two stories missing from the set that may cover the early years at Hedley. The first story I received is about the construction of a new road to reach the mine. It was four years after he arrived at Hedley. During these four years Wes designed and supervised the construction of a reduction plant, a large stamp mill, concentrating plant, cyanide plant, office, assay office and a hydro-electric power plant. Mr. Marcus Daly provided Myron Rodgers the funds to build these facilities that also included an electric ore haulage road and incline tramway. The tramway was the longest of its type in the world at the time. It was nearly two miles long and the difference in elevation between terminals is 3,600 feet. The flume for the hydro-electric power plant also was about three miles long. The reduction plant was built in the valley that was about 4000 feet lower than the mine in elevation.

The Hedley Supply Road

The equipment was shipped to the southern end of Okanagan Lake to the east of Hedley. Since the main part of the mine was above Hedley, the route to it from where the equipment arrived was long and arduous. In August 1902 Wes set out to build a new direct 38 mile road to the mine. Part of the Green Mountain Road from Penticton and the Apex Mountain Road to the mine site probably follow the old road.

Wesley Rodgers First-Hand: The Hedley Supply Road

The situation was this: All the camp provisions were hauled 40 miles from the base of supplies by freight wagons to the little mining town where we first out fitted, then packed from there 40 miles to the mine over mountain trails. It was decided to build a wagon road from the mine directly to the base of supplies and cut off approximately 50 miles. This was my job. We knew the general direction. There was not a trail nor a blaze of an axe to follow. I decided first to go through those mountains to get a general lay of the country.

A Frenchman who worked at the mine said that he knew way in general, but had not been through there for some years. He has two saddle horses; so I got him to go with me. The country was heavily forested for about 20 miles making traveling very difficult and keeping your direction. When we were out of sight of the mine, the Frenchman was confused; all sights were lost. We were traveling by dead reckoning and had traversed most of the area trying to find a way out of it. We could go up to a sheer precipice then take another direction. We were on a table land, trying to get down. After much angling and zigzagging we came to a slide of small stone – about the size of eggs but angular – and the Frenchman started to go down and I followed. That stone slide was resting on a steep slope which just needed touching to start it off. The Frenchman’s horse touched that slide, it started down, and I followed. My horse had a little better going, but I was afraid he would tumble end over end at times. We finally reached the bottom of the mountain without catastrophe; how I don’t know. There we tossed pennies on which way to go. The Frenchman, after talking to himself for a while, started and I followed. We were in a box canyon that we followed for perhaps a mile, when the country ahead opened up. We got out of the forest and came to a small stream, which we followed. Night was on us and still no signs of civilization. We traveled as long as we could see, but when the night became dark we camped. We ate some food promptly for we hadn’t taken time out for a meal en route. The Frenchman hobbled his horses, and we rolled up in our saddle blankets. When we awoke in the morning, we were hardly 800 ft. from the hotel. We traveled perhaps 40 miles that day through timbered land mountainous and no trail to follow, and of course, the traveling was rough. We got a room at the hotel and a stable for the horses, and took the next day off for both horses and riders were very tired.

The next morning we started back for the mine, following the same route we came out, except the stone slide, which was impossible to climb. The rock would slide at the least touch, and we could make no headway.

The Frenchman said that he remembered this place and that there was a place a mile or so ahead that we could make the climb, so we went on. Sure enough there was a place, very steep, but the ground was solid. At the top of the mountain, I blazed a tree thinking it maybe of some use in the future. A little farther on we came to a small stream, where we ate our lunch and gave the horses a rest. Two hours more traveling we were on the range we could see from the mine. We felt relieved. The distance now was but a few miles, and we were back at the mine.

The next day the Frenchman went to work at the mine, and I started to explore the range of mountains for the lowest pass for the road. I would start out in the mornings with a compass, aneroid, an axe, matches, lunch and a couple of 45s. There were in those mountains cougars, a few timber wolves and a few grizzles. The ax was for blazing trees and building a fire, when caught out at night, to keep all animals away. One is safe so long as he keeps plenty of fire wood on hand for the night.

A week’s search found the lowest pass. This pass was ten miles from the mine. The intervening terrain was not difficult for a location or road construction on an easy grade. From the pass ahead for 12 miles or so the terrain was terribly rough. At this point I got a helper. To locate a line through that section would require some time and maybe not possible. We bought out a tent and blankets from the mine and some food, on our backs and made a camp at the pass. The next day we put up the tent, fixed up our bunks, filled them with boughs of spruce and fir trees, and then cut wood for fires to run us for a few days.

The next morning we ran a line about two miles, when we came to a place which was at the head of the ravine and heavy with tangled underbrush. There was about 2 inches of snow where we started to go through which added to our troubles. We had hardly gone 50 ft. when we came to a place where a grizzly had been lying. There was no time to loose. We knew that grizzles would ambush a fellow, so we started for camp and never looked back. This was an ideal place for a “hideout” for a grizzly. The tangled mess afforded him splendid protection from storms. The next three or four days we spent in exploring the ground ahead of us. It was rugged, almost precipitous in some places. We were limited to a 10 percent grade, which is a little steep for long hauls for freight teams. After a week exploring that ten miles we got a line through by locating two switch-backs to give us the proper grade.

The distance from this point to the base of supplies was 12 miles and the ground was open, more rolling and no trees in the way. We were two days reaching our destination. We then went back to our camp and located from there to the mine. This line was all preliminary. We had to drive stakes on this preliminary line for the grading crews. This work required five men – two to go ahead and clear the line from all brush as this line had to be staked to the 10 percent grade, and other two to measure and set the stakes. This work done, we staked out a camp site at the halfway point. The four extra men were left to build this camp, consisting of one log cabin for the mess house and bunk house for five or six men, and a stable for six freight horses and one more for a saddle horse.

The grading gangs were now started to work, one at the mine and the other at the base of supplies, and they were to work toward each other. I remember the day very well. It was the first day of August 1902, bright and sunny. For thirty-five consecutive months before this there was not one month during which it did not snow. The falls in this country were remarkably nice and pleasant and this one was ordinarily better then usual.

The men worked hard. They knew that the company wanted the power plant installed and running before the winter set in, for after that the weather was beyond human endurance.

There was one colored man in the gang, working out from the mine, remarkable for his strength. He stood 6 ft. 8 inches and a perfect body. The boss put him on the four horse big iron plow, which was sometimes dangerous. Sam could hold the plow in ordinary ground, but when it struck a root or stone it would throw Sam down over the hill. Sam was good natured and would come back, ready to try it again. Every time I would go by I would holler at Sam.

The two gangs met about midway during the Holiday week. They were paid off, but six men and a cook were kept to widen out some places on the road. The men paid off, left after breakfast with their blankets on their backs, for the base of supplies, fifteen miles distant. They also took lunches along for safety. In the middle of the afternoon I also went on horseback. I went on into the dining room of the hotel and ate my supper. After finishing supper I went in the big pool room and bar. The men were having a good time. They had just enough drinks to throw their cares to the wind and enjoy life. Some were dancing, some singing. One fellow, who was naturally comical, had bought a complete outfit of clothes and was upon a pool table auctioneering off his old worn out ones. Finally, they saw me at the door and grabbed me and began yelling, “Gin up, gin up.” Big Sam was in the back of the room taking things easy. When he saw what was going on he came through that gang of men shouting, “Leave that boy alone. He don’t drink. He don’t drink!” Sam gabbed me from the bar and took me to the door and said, “Now Sonny beat it!”

The mining machinery was at the dock at the base of supplies, ready to haul to the mine. I learned of a man with a six horse freight team and a large freight wagon. I sent for him to come and look over the situation to see if he could haul the machinery to the mine, a distance of 52 miles. The road was alright except at one place where there was a sharp gulch and the road would have to be widened to make the turn.

The 40 horse power boiler was the first to be hauled out. While the teamster was loading the boiler on the wagon and hauling it to the snow line – snow was coming down the mountains at this time – and axe man was making a “go-devil” to take it to the mine on the snow. This go-devil was made from two trees about 18 inches in diameter hewn to about 6 inches thick and 14 ft, in length for runners. Three 8 inch pieces pinned these runners together 4 feet apart. These cross-pieces were scalloped in the center for the boiler to lie in them. The boiler was transferred from the wagon to the go-devil and chained firmly to it. The hitch to the go-devil was made about 4 inches to the left of the center of the go-devil so it would pull to the upper side of the road for safety.

The teamster hitched his six horse team and drove the teams with a jerk-line – he rode on the lead horse. Things went long all right till reaching that sharp gulch, referred to above. Getting by this gulch was dangerous. I stood behind “with my heart in my throat.” If the outside runner should slide one foot, the whole out fit would go down a thousand feet. The horses seemed to realize the danger, and they obeyed the teamster carefully.

He drove the six straight ahead as far as the horses could go. Then he swung the lead team to the left and dove the four ahead as far as they could go. He then swung the swing team to the left and drove the wheel team ahead with the load as far as it could go. He righted his six again ready to go. He hollered, “Steady boys!” These horses seemed to know exactly what to do. They started slowly till around the turn and were on their way again. That night we reached the middle camp for both men and horses. It was nice and warm and comfortable to get in out of the biting cold. The nights were long and the days short, which were a great help for we could not stand the weather on longer days. The snow, which fell a week or so earlier was well settled and got deeper as we approached the summit. The next morning, we realized that our toughest days were ahead. The snow being more compact and deeper required the teamster to break a road by driving only his team ahead and then returning and hitching to the load. We had, besides the teamster, four men to follow on foot to help out should anything happen. We were five days reaching the summit; all the way the road through the snow had to be broken by the team before taking the load. Our last day was the hardest – going through the pass. The icy wind was blowing in our faces, the snow was three to four feet deep and the weather 40 below zero. It was noon. We were cold, hungry and tired. We built a big fire as plenty of good dry trees were lying on the ground, being a burned over district. Our lunch was chunky boiled fat pork and a part of a loaf of bread and hot tea. These made a good lunch, under those conditions. We then made a dash through the pass and unloaded the boiler. The teamster with the go-devil and team and two men went back to camp and remained there till I returned. Both men and horses needed a good rest. They worked on after human endurance ceased. The other men and I went on to the mine to tell the boss that the boiler was at the pass and to go for it as soon as he could. After a days rest at the mine the men and I started back to the middle camp. The traveling through the deep snow for 17 miles was slavish, and we were tired and remained at the camp for another day to rest. Then we all went back to the base of supplies to get the air compressor.

The climate at that lower elevation was much warmer, snow had fallen in the valley so that we could take the go-devil to the wharf and load it directly. The air compressor was heavier the boiler, but being more compact was easier to handle. Then came the long hike to the mine, 38 miles. The road, however, being broken by the former trip, was much easier. We took this load all the way to the mine on the go-devil and turned everything over to the mine foreman.

I was glad to be relieved. However, these trying circumstances fitted me for what was ahead of me in the far north.

The Railroad Reconnaissance

After the mine had become operational in 1904, there was need of a railroad to provide transportation for the mine. On 22 September 1904, Myron Rodgers sent an engraved gold plate to his friend and former employer, James Hill, President of the Great Northern Railroad [1.2]. It purpose was to get him to build a branch line to the Nickel Plate mine at Hedley in the Similkameen Valley. It appears that Wes was asked to make a reconnaissance survey of the proposed route in 1904 probably before Myron sent the gold plate to Mr. Hill with the following engraved on it:

I beg to hand you hereby a product of the Similkameen Country from the Nickel Plate Mine and hope you will soon extend the Great Northern into the region.

A branch line was eventually built by the Vancouver, Victoria and Eastern Railroad, a subsidiary of the Great Northern Railway. It was part of Mr. J. Hill's desire for a third main line from Spokane, WA to Vancouver, BC. It was started about 1906 and completed about 1909. It appears that Wes started his survey about 1904 near Penticton, which is about 50 miles north of the Canadian border and worked his way west ending in Princeton. His route would have taken him north of Headley. It is not clear that his survey was used for one of the railroads that were built in the area. The line that serviced Headley came from Oroville crossing the boarder at Chopaka.

Wesley Rodgers First-Hand: The Railroad Reconnaissance

Some parties contemplated building a railroad through southern British Columbia and asked me if I would make a reconnaissance survey of the proposed route. Arrangements were made.

I started at a point in British Columbia north of Spokane, Washington and about 50 miles north of the International Boundary and was to take a westerly course to the summit of the coast range, a distance of about 160 miles.

The country was rough and very sparsely settled; there were only six white settlers along the entire route.

I left the beginning point at noon and a road for the first 20 miles or so, then the road directly south. There was a little ravine here and a long cabin. An old man was sitting outside it. Thinking that stopping places were far apart I should stop here, I asked the old man if I could overnight and get supper and breakfast. He said “Yes.” We talked for awhile, when his wife called us. We went in, and he introduced me to his wife. He said “Stranger I am 85 years old; this is my third wife and (I am) good another one. The next morning I started on my journey again. I entered a great forest about 40 miles through it. I had a compass, an aneroid (for barometric altitude measurement), an ax, plenty of matches, two 45s and a blanket on my back, roller up. This woods was difficult to get through. It was a virgin forest of big trees; at times there was tangled underbrush, very hard to get through.

There were a few grizzles, timber wolves and cougars, but I was lucky in not seeing any of them. I learned later – after my trip was over – that there was a camp of outlaws near the center of these woods, but their camp was farther north of my projected trip. It was said of them, that when they saw a stranger in that woods they shot him and buried the body so that no word could be carried out of their where-a-bouts. Not seeing any signs of their camp, I suppose that I was too far south. The going was very difficult and tiresome – many little gullies and ridges. Sometimes (there was) a high bluff, and I would have to “back up” and take another course around it.

I was now on my fifth day and beginning to think that my struggles would soon be over. I was tired and my rations were getting low. This fifth day I came to a cabin in a small valley, and an old man was hoeing out a garden. This was refreshing as I took it to be near civilization. Then, on the other hand, it may mean enemies. Had I seen him first I would have gone around him, but he was looking at me when I saw him. He had a real garden, quite a variety and all looking strong and healthy. He had some pumpkins – one great big one – as big as a bushel basket. I asked him what it was. He said, “Itaa – itaa – itaa – itaa – itaa – PUMP KIN!” IT was difficult to restrain my feelings and maybe dangerous to expose them. He was generous and friendly and said that six miles more would take me to the Similkameen Valley. The next day I reached the edge of the forest and could see the country – the first time for a week. There was a log cabin not far so I went to it to get something to eat.

An old Indian and his squaw were sitting on a wood pile. I asked, “I’m hungry, got something to eat?” He said, “Eggs!” I said, “All right I take them.” He went in the cabin and came out shortly with six eggs in a frying pan, fried hard and turned over. They were fried in bear grease. I could tell by the unpleasant flavor – putting it lightly.

It was a big relief to see daylight again. The walking was slavish through that forest and one never knows what he might run into. I was now in the Similkameen Valley. There was a wagon road for about 40 miles and from that to the end of my section was a trail, but it was good solid footing.

I came to an old small house one evening, which had no appeal for one to stay over the night, but on account of night coming on and no other place to stay; I thought it best to remain here for the night. The front of the place was nothing inviting, there was a slat nailed across the door, so I went around to the back. I knocked on the door, but no response. I knocked again and no response. I knocked a third time with the same results. I made up my mind to take chances of lying out, so went on. About five miles on I came to a nice well kept place – semi modern, two story house, painted white. There was a clearing of 20 acres or so. I went to the door and knocked. A very nice appearing lady opened the door. After greetings, I asked if I could get lodging for the night. Here is where my heart got jittery, as I had slept in my clothes for the last two weeks nor had I a clean face, nor shave. The lady went in and her husband – presumably – came to the door. I said, “I am making a trip through the country looking it over, and have not slept in a bed for two weeks. I’ll let you keep my guns, so you will sleep soundly.” He said, “Well come in and, and we will talk it over.” They were man and wife, along 40 to 48 years of age, cultured, refined and affable. There was an old man there whom I took for the father of the wife, and a little boy 10 or 12.

As near as I could make out they were city folks who went out there to spend their summers. They were 30 miles from their supplies. He had two pack horses and a saddle horse which he used for supplies. It took him about a week to make the round trip. Here is where I washed my face and shaved. The folks were so pleasant that I remained over till the morning of the second day. But they wouldn’t let me go. “You must stay a week with us, we want to hear about the ‘outside’.”

During our conversation the evening before, I asked about the party where I stopped but received no response. They laughed; then told me the story. There was a bachelor of many years who lived there, and who became weary of single blessedness and decided to light up his shadowy years, He first got the address of one of these LoveLorn agencies and wrote it to send him some pictures which it did. He selected a picture that met his wild fancies. He arranged to have her come via Canadian Pacific to a certain station, which I now forget – and to let him know the date she would arrive there. The distance was 75 miles to his home. All was well. The station was a lonely place with few houses and families. She was the only women who got off so there could be no mistake. She wasn’t just what he expected. He looked her over. She was stone deaf, wore a wig and had a wooden leg from her knee down. At first he was seized with indecision, then considering everything, he took her. This is what I saw when I knocked on the door so frantically.

I had a very pleasant time at this mountain home. They were simply gorgeous in their hospitality, but I could never understand how it could arise from that lonely, lonely habitation – sacredly ever seeing anyone during a whole season. Their interest in each other was above all thoughts. I never saw affection, such devotion between husband and wife and it was nice to see, but such richness of life seemed wasted in that boundless vastness of mountainous void. I was amused at his pet name for her. Her name was Helen – a name I always admire as a name for a girl. It leads me to think of Helen of Troy. But he called her by the first syllable, “Hel,” but she was also quick thinking and would come back at him with equal cleverness. I was on my way again and by evening I came to a nice house and large barn about the timber line. They were nice people – a family of husband and wife, a girl perhaps eighteen and an old lady. They were of a sect that I could not decide. I remained here overnight. The next morning I left and the wife gave me a lunch for I expected to reach my destination and return to the same place overnight, and I did. The next morning I started back on my long trek.

They told me of a cut-off of 30 miles to a place called Princeton, which would make Princeton a distance of 45 miles. They said that a man was to leave for Princeton, starting about a quarter of a mile ahead, where a trial lead down a ravine to Princeton, I waited there for a while, then started on for I wanted to make Princeton that night. I did not lose any time. I would run on the smooth places on the trail and walk and rest on the rough places. About the middle of the afternoon I got hungry. I saw a cabin ahead and thought I would get lunch. I knocked on the door and a girl, maybe twenty, opened it. I asked her if I could get a little lunch, that I was going on to Princeton and it was some distance yet. She said, “I don’t know, mamma is away and there is no bread in the house and I can’t bake.” I said, “Well, most anything will do.” She went back in the house and called me after a long wait. She had some cold venison, some warmed up potatoes and biscuits. She sort of apologized for the biscuits, saying that she could not get them to bake, so she cut them open and fried them. I said, “Oh they are good anyway.”

When I came in sight of Princeton, the man on horseback was a little ahead of me.

The Train Robbers

One of his last assignments at Hedley was to explore the surrounding countryside for other mining opportunities. During one of these trips he encountered train robbers who later on 10 September 1904 held up a train at Silverdale, about 22 miles east of Vancouver. The leader was Bill Miner [1.3] and his two accomplices were Tom "Shorty" Dunn and Louis Colquhoun. The three were arrested by the Mounties, and Dunn was the one that went with Wes on his look-around. He fired at the Mounties and was shot in the foot by them. Bill Miner or George Edwards was the subject of the 1982 Canadian film “The Grey Fox." He and his gang are still very much part of the Folklore around Hedley.

Wesley Rodgers First-Hand: The Train Robbers

From 1899 to 1906 [1905] I was located in south central British Columbia, at a gold mine. This mine was developed, the plant was completed and the mill was grinding out the gold. As the engineering work was done, except to keep the plant in operation I did not have much to do; so the company put me to looking over the country for more mines. I liked this scouting over the country very much, but sometimes these tramps were hazardous.

There was a range of mountains about fifty miles to our southwest which was my first adventure. The old timers told me that I could get a horse in there and that there were was plenty of grass. So I got some “grub” together, a small skillet and a small tin bucket to make tea, in preparation for my trip. I tied the bundle behind my saddle, also a blanket and an ax. It is always much safer to keep a fire going all night, on account of wild animals. The old timers told me that they were plentiful in that region. I had to go down the Similkameen River fifteen miles where there was a ford. The water was shallow here but swift. My horse knew how to take swift currents; so I got over in safety. After crossing the river there was a level stretch reaching to the foothills of a range of mountains I had to climb. This was an Indian reservation. The foothills were covered with forests, and to find a break in the mountains where I could get up with my horse was very difficult. I would go up through the forest and come to a cliff maybe a thousand feet high. Here I turned to my right and followed the foothills for a mile or so, the retrace my trail and go in the opposite direction.

About a half-mile I came to a stream which had cut its way through the cliffs where I got through but with some difficulty. The Indian was but a little way from this stream, which I wished to keep away from. An old timer told me that an Indian at that village had shot three white men there, but since that time he had been a good citizen. That was several years previously to my trip there, but that tragedy haunted my memory.

Permit me to tell a little story on this old Indian by way of digression. A party had built a log cabin not far from there – at least a traveler could get shelter and a meal – such as it was. This old Indian got in the habit of going there and loitering around and became sort of a pest. The boys thought that they would play a trick on him. They put some charges of dynamite around the place – far enough away not to endanger the buildings. The next time the Indian came around the boys touched of the dynamite. When the third blast exploded the Indian jumped on his pony and the last that was seen of him he was disappearing with his arm up as if for defense. After a month or so he came back and said, “White man all death.”

Now to return to my story: Having reached the top of the cliffs my horse and I were both tired and hungry as we had no place to stop and lunch. I walked and led my horse back from the water falls so as to be out of hearing from them. Old timers told me never to camp near water falls, for one could not hear the approached wild animals. There was good grass there too so I picketed my horse and got some lunch for myself.

That night the moon was full and bright. I never saw the moon so silvery. There was no dust in the air and her beams seemed to fall sort of fluffy. There were some cotton wood trees there, the leaves of which were turned yellow by the frost. The beams of the moon falling on these leaves made a beautiful contrasted picture. After looking at this picture, which I had never seen before, I threw some wood on my fire, rolled up in my blanket and fell asleep. About 2 o’clock I was awakened by a loud snort from my horse. I thought to myself, “cougar.” I grabbed my 45 and ran to him shooting off my 45 as rapidly as I could pull the trigger. The shots crashed like a cannon to that valley, and I did not think that the cougar would stand for it, which he didn’t. If he had, I had another 45 to fight him at closer quarters. My horse was badly frightened and was pulling on his lariat, which I was afraid he would break. I called to him, but he didn’t hear me, and I was afraid to go to him directly. He ceased pulling in a few moments and heard me call. He turned and saw me and ran to me and rubbed his nose on my chest, he was so glad to see me. He was shaking and quivering. I patted and talked to him, then loosed him and took him to the fire. He seemed to know that fire was good protection. I tied him close to the fire then lay down and tried to sleep some more. That cougar climbed up higher in the mountain and howled till day light. My sleep was over. If any person can sleep while a cougar is howling he better see a doctor quickly for there is something wrong with him.

Horses seem to know that fire is good protection. Old timers said that too. I was more convinced of this too, later on, when a pack of wolves in Alaska followed me for about three miles. I fortunately took a lantern with me and going home a pack picked up my trail and were not long till they were up to me. I kept my 45 in my right hand and carried my lantern in my left hand ready if they made an attack. But they did not come closer than twenty feet or so. There were six or seven of them, and they circled around me snapping and snarling. They had the most fiendish yellowish eyes, which I cannot describe nor ever forget. They were terrifying. I thought that if they kept away from me that I would not start to shoot. Better let good enough alone. I watched the trail too fearing that I may fall as it was not very good. Old timers told me that wolves would be on a person before he could recover. The next morning, the postman came to camp and knocked on the door. I opened it, and the postman said, “My God, are you here!”

Now returning to my story. After breakfast and fixing my lunch, we continued our journey. I figured that we had about twenty-five mile yet to go. There was no trail to follow and the traveling was rough but not steep. The sides of the mountains were flattening out some and covered with grass – good place for game. There were two places where cougars had eaten half a deer. This was country of the big horn, but I saw none. These animals are too wary to be seen casually. The time was getting on towards evening, and I began to look for a camp site. Old timers had told me never to camp in a forest, but in a clearing for wild animals are slow to attack in a clearing. A little further along I noticed a clearing across the stream, which was small, and crossed it.

At the edge of the clearing, I stopped and looked around. About 100 feet to my right was a man standing in front of a tent and looking right at me. I was seized with a terrible fright. I thought to myself, there are the train robbers. He did not look like a prospector. He had on a broad rimmed hat, a red bandanna handkerchief around his neck and a couple of guns in his holster. It was too late. Had I seen him first, I would have turned and fled. That would have been fatal after he had seen me for I knew that there was another man around somewhere with his finger on a trigger of a 45. I knew too that it was the custom of criminals to hide themselves away in mountain vastness, build a log cabin and live there to escape the law. I knew too that when a stranger happened through the country near the cabin of the criminal that he would shoot the stranger and bury the body so that no man would get out to the outside. Well, I rode up to him and told him my story, that I was from the mine over on the Similkameen and that the company sent me over to look over the country for new mines. That I was just looking for a place to camp. He said that I could camp with them. I got off my horse, unbuckled my holster with my two guns and handed them to him. The old timers told me that if I ever met with such a situation, to surrender my guns the first thing, as I would be much safer, that if kept my guns they would keep me covered all the time and if I should make a move which they suspected, they would have the drop on me. Another thing the old timers told me, never let them catch me in a lie, that it would be fatal. The night I was very tired having had no sleep for so long and had traveled so many hard miles. They talked to me and questioned me till late in the night. They feared that I may be a scout for the Canadian Mounted Police, and they wanted to make sure. I felt that I was in the hands of fate, and so tired I didn’t care either.

The next morning the man I first met and I took a stroll around the country looking for showings of mineral. We found none, but did find a geological feature that was of interest. It was an extinct volcano, or rather the core of one. This core stood perhaps forty feet high and the enclosing rock had fallen away from it leaving the core very smooth. I climbed over the blocks of rock and put my hands on the core which was smooth, and I wondered how many millions years old it was.

That night I got some sleep, but not much rest, as I slept on the ground. The next morning I took my leave. I bade them goodbye and invited them over to the mine some time. As soon as I was safely out of sight I urged my horse all day over the rough ground and never stopped till back at the mine. My horse played out and refused to go further. I got off and talked to him and patted him then led him the rest of the way.

Thirty days after this these men held up the Canadian Pacific Transcontinental. The Canadian Mounties were quick on their trail. They caught up to the robbers and the younger man – the one which I first met – opened fire. His shots went wild, but the first shot from the Mounties brought him down with a broken leg. He was taken to the Provincial Penitentiary. The other train robber proved to be an old hand at the game whose name was “Bill Miner.” He got out of jail by having some important papers, which I understand he surrendered for his freedom. My next contact with Bill was in North Carolina [Georgia]. He held up a train there, was caught and jailed and died there.

The Bering River Coal Field

At the end of his work in Hedley, Wes went home and married before his brother Myron called him back to action for a second time. This call was to assist Myron in developing the Bering River coal field and building a railroad into it for the Guggenheim interests that were part of the Alaska Syndicate [2.2]. The Syndicate was trying to develop the mineral rights in that area of Alaska. The Bering River coal field development was under the Katalla Company that included the Northwestern Railway Company. It became known as the Copper River & Northwestern Railway Company (CR&NW) when the Syndicate acquired the Copper River Line. It also included the Bering River Line and the Copper River Branch Line. The Bering River Line was to serve the coal fields and a competing line to it was the Bruner Line.

Michael James Heney [2.3] began to build the Copper River Railroad from Cordova in 1906 to serve the Kennecott Copper Mine, but retired and sold his interests to the Alaska Syndicate in October 1906. However, by this time the Syndicate had decided to build a deep water port facility at Palm Point near Katalla to serve their Bering River coal fields. Myron Rodgers had proposed a solid rock breakwater that was to be 2100 feet long with a 1100 foot wing. It was to be built using huge boulders to withstand the storms.

The Copper River railroad was to be connected to the Palm Point facility by the Copper River Branch Line, and Myron Rodgers took over the construction of the line along the Copper River. The base of operations remained in the Katalla area. In 1905 both Myron and Wes had moved their families to Settle, Washington to be closer to the work at Katalla, Alaska. It was about a week's journey by ship from Seattle. However, Myron had a log house just outside the town of Katalla that was his base. He was the Chief Engineer of the Copper River & Northwestern Railway Company, and Wes worked for him as a surveyor and construction superintendent.

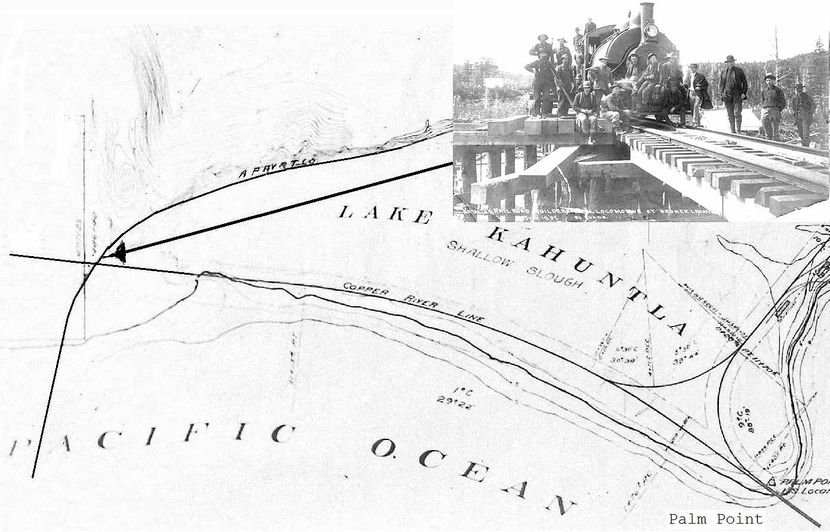

In the winter of 1907 a major winter storm destroyed most of the Katalla facilities including the rock breakwater. When the storm came, the Copper River Branch and Bering River Lines only were completed about five miles from Palm Point. Other sections of the Bering River Line roadbed had been established as far as Carbon Creek, but no track was laid or the connecting bridges built (see map above). The coal claims also came under review by the government and many were canceled or set aside. With the storm destruction and the turmoil over the coal leases the Syndicate gave up on the Bering coal fields. They then refocused their operation on the copper mine and building the railroad from Cordova to the copper mine along the Copper River. Myron Rodgers left, and the Syndicate hired Heney to supervise the construction.

During 1906 Wes spent his time surveying the coal fields, documenting the coal claims for the Syndicate and other parties. He also did surveys to locate the best routes for railroads to connect the coal fields to port facilities. Surveys were conducted along the southeast side of the Bering River and on the northwest by Katalla. As noted above the Katalla route was selected over the one on the southeast side of the Bering River. However, the Bering route was later used by the Alaskan Anthracite Railroad. By 1920 Wes was listed in the Office of United States Cadastral Engineers, Juneau as a United States deputy surveyor, a United States mineral surveyor and a US deputy mineral inspector [2.4].

Wesley Rodgers wrote two letters and four stories about his experiences related to the The Bering River Coal Field that began in 1906. The first was a letter dated 17 June 1967 to his nephew about locating the railroad southeast of the Bering River. The second was a story about building the Copper River and Bering River lines and the next two stories were about the back country and the conditions there just before he went back to Seattle for the winter. After he had left, the winter storm in 1907 destroyed much of the railroad he had just built. In 1908 he had just joined his brother at a copper mine on the Portland Canal in British Columbia when he was called in February to resurvey the Alaska Petroleum and Coal Company anthracite claim he did in 1906. It was part of the claims that were under government review. After the settlement of the claim he was called in 1917 to build the railroad to this anthracite coal field. His remaining story and letter concern the survey of the anthracite coal field and the building of the railroad, the Alaska Anthracite Rail Road, on the southeast side of the Bering River. This line which was surveyed in 1906 survived and operated for a number of years before going bankrupt.

Railroad Location

In 1906 Myron and Wesley Rodgers went to the Bering River Coal Field area to locate the fields and find railroad routes to serve them. One route was on the southeast side of the Bering River and the other was to the northwest going through Katalla. While the southeast route may have been better, the line through Katalla was selected because it could join the Copper River Railroad from Cordova and serve the Kennecott Copper Mine. After the Katalla project was abandoned, the Bering River route was used by the company that took over the Anthracite field.

Wesley Rodgers' letter describes one of the explorations for this line near its upper end were there are mountains. He and a group of men set out to find a way to the coal fields, but their experience also may have been a reason to select the Katalla route.

Wesley Rodgers First-Hand: Locating the Bering River Railroad

One year, I think 1906, we were locating a railroad down the Bearing River Valley, when we were over taken by a terrible storm. We had proceeded to a place where we ran out of land. - This is not unusual. - I called for our guide. We talked the situation over, and he suggested that we camp right here, take two more men and scout ahead a few miles. This was a good suggestion. We took two trappers, thinking that they could withstand the trip better than others. So the next morning we rolled our blankets with enough food to last a week.

We had gone four or five miles when we came to a swamp. The guide cut a stick and began to measure to see how deep the swamp was. The swamp was about knee deep, so we went about a mile ahead. There was a heavy black cloud rising ahead of us. The guide said, "We better wait here till we see what that cloud will mount to. Jim the guide picked out a land mark on the mountain to our right then we waited for the storm. We did not have long to wait. The wind, the darkness and the rain came on with a fury. We were soon drenched. The guide said that we would have to stand there till morning. The storm had calmed a little - enough to pick up our land mark. I said to our guide, "Jim could you go over to the mountain to our left and find a Projecting rock for us to get under?" The two trappers and I were feeling the effect of these privations, and we were afraid we may not be able to get out of the swamp. So Jim started out with his pack of blankets, the gun and the ax.

We waited in suspense, as we were soaking wet and cold and hungry and thirsty. We waited for three or four hours, when we heard a gun shot, which meant to come on. the trappers and I were stuck in the swamp. We tried every way but without success. Finally, one of the trappers got his feet out of his boots; then in his stocking feet wiggled his boots out. Then the trapper wiggle the other trapper out. The two of them pulled and twisted at me till they got one foot out. The other one was much easier.

We then started across the swamp to find Jim. Jim was scarred as badly as we were, the white in his eyes showed it. He was afraid we might get lost in the swamp. We had a small tent too, to drag or carry turn-a-bout. Jim said, "You boys drop your packs and follow me." He had found a small bit of ground about four feet above the level of the swamp which he used for camp, my but Jim did work. That small tract of ground was covered with brush and small trees. .Jim had it cleared, stakes and ridge pole made and had the tent up in little time. Then he cut arm full of branches of spruce and pines and put them on the ground in the tent for us to sleep on.

He brought over our packs. One of the trappers had his blankets rolled up in a canvas sheet, which Jim spread over the boughs. Then he spread over the canvas a pair of soaking wet blankets. He placed us in there on the wet blankets with our clothes on, including our boots. - We had on hip rubber boots. Over all of this he spread over us one more wet pair of woolen blankets. Then Jim went to the thicket and dragged in small dead trees, which he cut in small lengths and soon he had a fire going. He found a spring of fresh water and he made tea for all of us. My, it was so warm and so good!

Jim got the sandwiches and warmed them in a skillet we brought with us. My they were good! This was the first food we had for thirty hours. Jim dragged more wood in and kept the fire going all night.

On the early morning of the third night out Jim got up and put some wood on the fire. When he got back he stopped and said to me, "Rodgers do you know that you passed out last night?" I said, " No Jim, I didn't know a thing about it." "Well you did and I had a hard time getting your lungs to take up their work again. I worked your arms and pressed in on your chest, but it did no good. Well, I said to myself I'll try just once more. I put my mouth to your mouth and filled your lungs till they were full. Then I worked your arms and pressed to expel the air from your lungs and to my great surprise the lungs took up their work again."

I said to Jim, "How would it be if we get ready and leave for camp just after dinner today?" Jim said, "It would be better to leave in the morning and have the full day ahead." So we did. Jim lead off, and we followed him. It was about six miles to camp, and it took up nearly the whole day. When Jim saw the camp, he let out a wild yell. How those boys came tumbling out of that big tent yelling, "We are coming, We are coming!"

The two trappers and I sat down our legs refused to go further. Two of the boys took a shoulder and carried us or dragged us the rest of the way.

The Building of the CR&NW Railroad

There was much discussion as to the best place to locate the port facilities for the Bering mines. It was decided during the planning stages in 1906 to build it at Palm Point. When Michael James Heney sold his Copper River operation to the Alaska Syndicate his railroad was then to be connected to the Bering River Line at Palm Point. This new railroad venture was now known as the Copper River and Northwestern Railway (CR&NW).

The battle for the coal claims would go on for many years due to a number of government regulations, but the railroad at Katalla was started in early 1907. At the same time a second group began building the Brunner Line (Alaska Pacific Railway and Terminal Company) parallel to the CR&NW. They were trying to take control of the rail access to the coal field and sell it back to the Alaska Syndicate. This competition would come to a head in early 1907 when the two railroads met northwest of Palm Point. The Syndicate won, and the Brunner Line had to cross the Copper River Line at grade level as shown below. In the photograph of 14 July 1907 only the Copper River line had tracks.

In the end after the storm, the Alaska Syndicate gave up on the coal fields and moved their operations to Cordova and focused on the copper mine. Michael James Heney came back to work for them to finish the railroad he had started in 1906. The Brunner line went bankrupt, and both railroads in the Katalla area were abandoned.

It was early in 1907 when the ship with the first railroad construction crew arrived at Katalla. Wes in his first story describes the arrival and unloading of the ship, which occurred just north of Palm Point. The support base can be seen on the right edge of the above map. He then tells of the battle with the Brunner line that tried to cross the Copper River Line just northwest of Palm Point.

Wesley Rodgers First-Hand: The Building of the CR&NW Railroad

The big ship "Whatcom" heavily loaded with human and material freight cleared Cape St. Elias out of the storm lashed and mountainous sea into the lea of Kayak Island. In these protected waters she ceased plunging and rocking and twisting and rolling. For five days since she left the quiet waters of Puget Sound and headed for the open at Cape Flattery, she encountered violent gales. Some of the rigging torn away, the life boats gone and the pumps laboring to capacity in a losing battle, testified to the impetuosity of the storm.

As the big ship quieted the passengers crawled from their bunks where they had gone early in the voyage and had not from there since. The seamen and skipper did not escape the dread sea sickness from the constant rocking of the ship. They were nearing their journey's end and the brightening hope of landing turned the tide of their ebbing spirits and dispelled their thoughts of hardships of the past few days.

The engines ceased but although a mile or so from the shore the skipper dropped anchor as the deep chested siren gave notice that the voyage was at an end. The passengers had breakfasted; it was the first food that many had taken for four days and they were now on deck in happy spirits. The ship lay at anchor waiting for the lighters to come out from shore, but they were detained, noon time came and the passengers had another good "square," which greatly contributed to their regaining strength. Everyone was in a gleeful mood; good humor existed everywhere which is always found on shipboard when such occasions arise. But that great joy and merriment was soon turned to grief. The skipper observed through his glasses that the serf had not abated enough since the storm to risk the lighters for unloading of the passengers and freight. The donkeys began to hiss and steam and crunch at one another, the bells clanked in the engine room and soon the big ship was full speed ahead. She did not, however, take a course for the open ocean, but to the Northward through the more or less protected waters of Prince William sound. After supper the passengers, for the most part , retired to their bunks for the night. Under their keen disappointment and unknown where-a-bouts and broken strength from the voyage they needed sleep, rest and food.

The next morning their sleep was ended by the breakfast gong. During the night the ship had entered a long well protected arm of the sea and plowing through the glassy waters tied up to a wharf unknown to the passengers. This was Valdez. It was about the middle of March and this town had not yet crept out from under the winter blanket of snow, which was melting. The town people said that it had for the most part gone; it was then down to the roofs of the one story houses. the people got in and out of their houses through the snow through tunnels. A dog sled track was kept open through the middle of the street for delivering freight, express, groceries, etc. To see Valdez proper one would have to return latter in the season. the passengers idles away their time for the next two days, eating and sleeping mostly, to bring their wasted bodies back to normal, for the hard work ahead of them would be wearing and consuming on their strength and resources. The skipper had been watching the his barometer and decided that the time would be about right to disembark on the evening of the second day; so he gave the half-hour whistle. The superintendent, said by chance, "You will leave us off on your return trip?" "I have no clearance South-bound.", the captain replied rather briskly. The superintendent rushed down the gang plank and over the quarter-mile plank-driven driveway to the cable office (US Army Signal Corps had laid an undersea cable to Valdez in 1905.) As the last whistle blew he made the gang plank, returning just as it was hauled aboard. The bells clanked, in the engine room as the skipper shouted, "Leggo the bow line, Leggo the swing, Leggo aft." And the big ship pulled away from the wharf out into the arm of the sea and disappeared into the darkness. The superintendent went to the bridge and handed the Captain a yellow envelope.

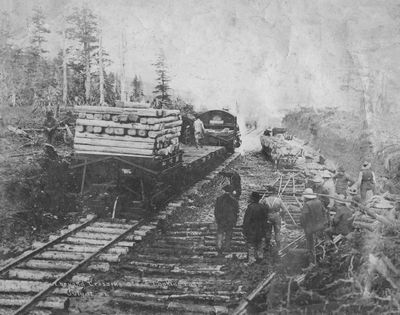

The next morning before day-break the passengers were aroused from their sleep by the siren breaking the silence of that Northern night. After it ceased blowing its echo could be heard reverberating against the mountain range a mile or so back from the shore. At the same time the gong rang for all out, as breakfast was only a half-hour away. Breakfast over, day-light was gradually breaking and the tugs could be seen leaving shore towing the lighters for unloading. A new era had come. The parapets of the kingdom of the silent North were about to crumble and that kingdom was about to end. The "handwriting on the wall" appeared the season before when corps of engineers had searched the North's fortifications for weak places where they might attack. The North jealously guards her treasures and only the valiant and the unafraid, capable of enduring long and outrageous hardships can over come her fortifications and enter that land of treasure and mystery. An army of invasion was now at her gates, laying siege to that kingdom, training its guns on its parapets with the intention of destroying them, entering within and looting her stores of wealth. But, these guns were axes, picks, shovels and all modern equipment for railroad construction.

The work of disembarking was now at hand. The first load sent ashore was men, shovels, axes, the big tents, etc. The superintendent divided the men into gangs with bosses over them. The first work was to erect the big mess tent to feed one hundred men at one sitting. The snow was about four feet deep and in the spring of the year was compact and solid. A gang was set to shovel away the snow for the big mess tent; others were sent to the forest to bring poles and stakes, others were to find fresh water for domestic use; still others to clear sites for the big bunk tents for two hundred men that night. The men worked with feverish speed. the day was nice and bright and warm. At ten o'clock the big mess tent was ready, the cook stove set up and at noon the cooks and flunkies had dinner prepared for two hundred men.

After dinner gangs were placed to clear sites for other large tents stores and warehouses; for food had to be brought from the ship that day and placed in camp, least the weather should break and the men cut off from food supply. Days were few and far between when landings could be made, for as yet no wharf was built and all the supplies had to be landed directly on shore. By night-fall a good day's work had been done; the mess tent, the stores tent and the warehouse tent were all up and the stores were landed from the ship. the last load of spruce boughs was placed in the last of the two hundred bunks as mattresses. Heating stoves were in the tents and plenty of wood cut; so the men were well fed and comfortably cared for , for the night.

The next day the construction of the permanent camp began. Other sites were selected and the snow shoveled away for mess houses, bunk houses, stores, commissary, warehouses, office buildings, engineers quarters and several auxiliary buildings, all built of lumber. This building material was yet to be brought from the ship and carried ashore to the sites when the construction began. This work also was rushed in order to get the men housed in more comfortable quarters before the weather broke. It is not always possible to securely fasten a tent to the ground, and if not, the wind, which often rose to violent gales from sixty to eighty miles per miles per hour, may pick up a tent bodily and carry it away.

While the construction of this permanent camp was in progress, the unloading of the rest of the ship's cargo was rushed. This consisted of construction equipment for the building of a railroad, which was the object of this expedition. The cargo consisted of construction cars, railroad rails, engines, logging engines, steam shovels, pile-drivers, saw mills with boilers and engines, cables, axes, peaveys, cross-cut saws and many other less important but necessary tools. Then duplicate parts of much of this machinery had to be carried in stock because the base of supplies was over twelve hundred miles distant.

The weather remained calm and by evening of this second day the big ship was unloaded and she steamed away in the darkness. The next day - the third day- the finishing touches were put on the camp, which were neglected, through haste during the first two. The work of assembling pile-drivers, steam shovels, saw mills and logging engines was begun. The engineers began shoveling snow to find their stakes of the location line, which was run the year before. By the first of April the snow was about gone and actual railroad construction was begun. The steam shovels were set up at grades to begin work, pile drivers were brought into place and saw mills were taken to the edge of the timber. The first pile was swung into place, the ponderous hammer, tripped from its moorings and dropped with a terrific thud. The donkeys of the steam shovel hissed, puffed, raced then slowed down and the first dipper full of earth was swung around and dropped on the grade. Railroad building had begun, and a new dynasty set up.

From this point on the coast line, two railroads were to be built. The objective of one was the Bering River Coal fields and this branch turned to the right. The object of the other was the Copper River and it turned to the left.

Railroad building had scarcely been reduced to routine, when another railroad interest landed about a mile further north. They also began railroad construction. Their objective also was the Bering River Coal Fields. This would more or parallel the other branch, but would cross the branch to the Copper River. It was evident that trouble was ahead. Both outfits were making good progress. The first party in the field had driven about a half mile of trestle through a shallow lake and were moving along with splendid progress. There was a difference of grade of the two railroads where the crossing was, of about three feet. For practical purposes this much difference was impractical. Resistance by both the railroads interests was now plainly seen. One day when men of the first party, let me say to distinguish from the second party, which came later, were at dinner, they heard a terrible explosion. Rushing to their work, they found their pile driver blown "off the earth," and quite a length of their trestle in ruins. From this time on excitement ran high. The avowed policy of both parties was force. The first party assembled a new pile driver and rebuilt the ruined trestle. While the first party was assembling their pile driver, the second party outfit a large float of big logs bolted together, and placed it in the lake in front of the first party's trestle. Then they fastened a large cable - steel cable- to each side of the float by means of eye bolts. These cables extended back from each side of the float two hundred feet or so to a logging engine. By jerking this float backwards and forwards by these engines it was impossible to drive a pile, so progress by the first party was deadlocked. This was a new engine of war and the superintendent was for a while perplexed. He wired the situation to the head office at Seattle. Four days later a ship from the south steamed into the bay and dropped anchor a mile or so from shore. The purser sent for the superintendent who at once went out to the ship. The purser met him at the top of the rope ladder and handed him a letter and a package. He open the letter and read, "Mr. ---- ----. General Superintendent," "You are in a country where there are neither laws of God nor man." "You will find $50,000 cash in the package to be used as best seems to you." "Make the crossing." The superintendent was seized by the most opposed feelings. He read it again and again but could not for the time discover a solution that appeased his feelings. He claimed down the rope ladder into his launch and went ashore. He went to his office and meditated deeply over the tide of affairs. What he feared most was bloodshed. He called the head bosses and the chief engineer to a meeting at his office that evening and disclosed the information to them. They discussed the situation long into the night and came to a conclusion that the float must be destroyed first, then push on as fast as possible. At this meeting they decided to offer a reward of $1000.00 to anyone who would go aboard the float and server those steel cables. There was a professional gambler at the village who had just "gone broke." He was, for the most part, a lucky gambler and when his luck was with him he could "break the house." He needed money badly. He reasoned that gambling was his business and why not gamble with life. There were coiled cables on the float too, jerked by the logging engines, for the specific purpose of keeping "dare-devils" off. The gambler accepted the offer. The company furnished him with a skiff and a large hammer. He rowed to the float, jumped upon it, dodged the coils of cable, then with the hammer he struck one of the cables at the eyebolt. Watching for another chance he struck again, then with the third blow he served the cable. He quickly jumped into the skiff and rowed ashore. He had gambled with life and won. The first party, unopposed, began their advance again. It was a few days when the second party employed all their men, by various means, to obstruct progress. The $80,000 cash was about to play its part. One evening, after supper was over an hour or so, with every indication that the weather would be fair, every available man was ordered back to work. The first party had engaged two powerful Irishmen brothers, Red and Jim. They were about six feet six inches tall, well built, and they did not know their strength. It was said that either of them could lick any six men in Alaska. But they were not men that were quarrelsome, but rather of good nature. Red and Jim were to lead the 'fighting squad' that were stationed handy and were to advance when signaled There were only a few bents of the pile trestle to be driven, then all the work would be grading.

As soon as the crew of the first party returned, after supper, and began work, the crew of the second party rushed out and threw every impediment in their way possible. From that time on it was a 'free-for-all." Red and Jim were signaled to move forward, with their forces, to clear the right of way of the opposing force. They went forward with a bound and shoved the men off the right of way and cleared it of debris. The graders then of the first party were sent forward to grade the road bed. As fast as the grading was done the track gang carried forward ties and rails and laid the track. The opposing faction retired for a brief spell, when all of a sudden a blast was set off in a bank of gumbo. This gumbo was jet black and sort of greasy. No one was hurt badly for a while there was nothing but confusion. The forces of the first party received the full force of the explosion. They were not only bespattered with the black mud, but it was in their eyes, their mouths their ears and hair.

It was necessary for them to wash, so they went down to the lake and washed their eyes and ears and hair. This took some time. While they were gone the other side took up the rails and threw them into the lake, cut the ties in two and destroyed the grade. As soon as the crew of the first party was through washing, they marshaled their forces and rushed the opposing faction. Red and Jim were merely play before. These two "Goliaths" rushed on the opposing faction. Every man they hit went down with a thud and had to be carried to the hospital. They rushed to the thickest of the fight and men fell away from them like ten pins, so terrific were their blows. They soon had the right of way cleared again, graders were sent forward again, then ties and rails. The men worked feverishly. They graded a hundred feet or more beyond the crossing of the second party's railroad, tore up their tracks and laid their own. The objective was achieved, the crossing made. It was about six o'clock in the morning when they returned to camp. Guards, heavily armed were placed at the crossing to insure no further damage would be done.

Summary: The Building of the CR&NW Railroad

A search of various archives and web sites uncovered additional material that has provided a better understanding of the railroad and the related facilities that Wes described in his story "The Building of the CR&NW Railroad."

The "Whatcom" was previously known as the "Majestic" and by today's standards not a large ship [2.5]. It was 657 Tons and 169 feet in length. However, it appears to have carried quite a load of passengers (over two hundred) and material and equipment. The first morning they unloaded the supplies to build the base camp and by noon they were ready to feed the two hundred men. Wes reported that by that night all the stores were in the warehouses and the two hundred men were in beds in a heated bunkhouse tent.

The next day the rest of the ship was unloaded for the building material for the permanent camp and the construction equipment for the building of a railroad. The equipment consisted of construction cars, railroad rails, engines, logging engines, steam shovels, pile-drivers, saw mills with boilers and engines, cables, axes, peaveys, cross-cut saws and many other less important but necessary tools. It was a lot of equipment for the "Whatcom" even if it was disassembled.

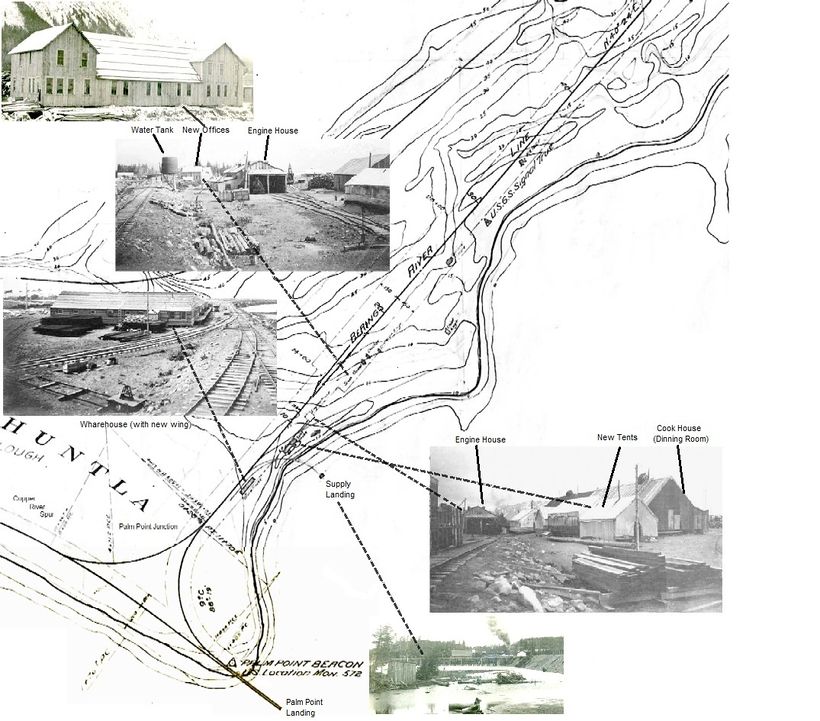

The equipment like steam shovels and pile drivers came in pieces and had to be assembled at the site. Even the 0-4-0 locomotives had to be assembled as shown in the photograph on the left. The photograph of this area where the engine was assembled is an early one before the engine house was built. The other nearby faculties in the area also were rebuilt after this photograph was taken.

A map was located that details much of the construction described by Wes [2.6]. Its title is shown below, and it has Station Marks every 1000 feet on the Bering River Line. They begin at Palm Point and are in hundreds of feet (x0).

| Station | Approx. | Coordinates | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 00 | 60°10'47.44"N | 144°33'30.36"W | Palm Point Junction |

| 10 | 60°10'55.60"N | 144°33'17.02"W | Railroad facilities |

| 20 | 60°11'3.85"N | 144°33'4.17"W | - |

| 40 | 60°11'20.33"N | 144°32'40.92"W | - |

| 60 | 60°11'35.17"N | 144°32'19.01"W | - |

| 80 | 60°11'49.60"N | 144°31'55.50"W | Katalla Area |

| 110 | 60°12'15.32"N | 144°31'22.33"W | End of map |

| KT | 60°11'42.03"N | 144°31'16.02"W | Katalla Town |

The Map Title and the Bering River Line 1000 foot Section Locations

The map shows three railroads - the Copper River Line (branch), the Bering River Line and the Brunner Line. The Brunner Line is marked APR&T Co and is not part of the Katalla Company, but came under the Alaska Pacific Railway and Terminal Company, Katalla and Bering Lake Division. The CR&NW Bering River Line was to serve the coal fields, and the Copper River Line was to connect to the railroad from Cordova going along the Copper river to the copper mine. [2.3] There also were other railroad projects in the area under consideration [2.7, 2.9 and 2.8].

Based on the Katalla Company map and other information, it has been possible to show the layout of the base camp and the Supply Landing. It is the most likely place where all the supplies were brought ashore from the "Whatcom" and other supply ships that followed.

(P11-034 Map showing Katalla Area (railroad map)

P11-095 Katalla Co. construction camp with beach in foreground (Supply Landing)

P11-013 Katalla railroad yard [?] (Warehouse)

P11-098 Katalla railroad yard including several tent facilities (Cookhouse)

P11-014 Katalla railroad yard with engine in center building (Engine House)

P11-109 Large newly constructed building near waterfront. (New Offices)

This main camp was located near Station 10, which is close to the Supply Landing and about 1000 feet north of the Palm Point Junction. The camp is detailed by inserts that show the buildings that were built in stages during 1907. It appears that tents were used again later in 1907 to supplement the Dining Area that began as a tent before the wooden building was constructed. The picture on the left shows a 15 foot cut at Station 65 (6500 ft.) on the Bering River Line looking northeast towards the town of Katalla. The locomotive is one of the 0-4-0 engines, and on the right are some narrow gage tracks used for construction with a construction railcar that may have been self-powered.

The major winter storm in November 1907 destroyed the facilities along the coast including the Palm Pont Landing and parts of the Copper River and Bering River Lines. Its destruction reached the main camp and inland to the town of Katalla. The photograph below is a panorama taken from Palm Point that shows the main support base in the distance and in the foreground the rocks that were part of the Palm Point deep water port facility. It was the key to the railroad operation from the Katalla area.

The Final Check - Bears

The first 1907 backcountry trip that Wes Rodgers wrote about started at a camp near the entrance to the Carbon Creek Valley. (He identified it as the Carbon River in his story.) He was at a railroad construction camp, and one has been identified at this location. With his Indian guide, he went up into the mountains for one last check of his notes on the coal fields that were to be served by the railroad. They traveled up Carbon Creek for about two miles before climbing to the top of the Kushtaka Ridge where they encountered the bears.

The next day in early October 1907 Wes and his men left for their base camp near Katalla. It was a long walk to the Bering River where they were able to get a river boat down the river and on to Katalla via Katalla Bay. While there are roadbed scars for the Bering Line from the Carbon Creek camp going back to the Katalla base camp, the track that was laid ended on the northwest side of the Katalla River. The bridges had not been built by this time across the Katalla and Bering Rivers, which is why Wes and his party went by river boat to Katalla.

Wesley Rodgers First-Hand: The Final Check - Bears

It was late in October 1907 when we broke camp on the Bering River Coal Fields Alaska. This was the usual time to abandon all outside work, in the outlying camps, unless detained by some unfinished work. After October, storms were certain and violent, but uncertain as to time. To be overtaken by a storm in that time of year meant terrible suffering from exposure, at least the very least, and often losing men. The weather had not shown any signs of breaking, but we took no chances. While the boys rolled their “blankets” and made final preparations for leaving the next day, I took my Indian guide and went over the season’s work in the field for a final check on my notes. I never could remember my guide’s native name. It was the most difficult name to remember I ever heard. But his Christian name was “Frank,” and he always went by that name. He was a pure blood Indian, solidly built, not very tall – perhaps five feet six inches – honest, willing, dependable and the best man on the trail I have ever saw. It made no difference to Frank whether it was rough mountain trails, mushing those terrible swamps over knee deep or fording those swift glacier streams of mud; he was speedy.