Artificial Heart

Heart disease is one of humankind’s most pervasive killers. Often, heart disease may be so severe that a patient has little chance of surviving while he or she awaits a donor heart. Taking their lead from the successful invention of an artificial kidney dialysis machine in the 1950s, medical scientists began to work on creating an artificial heart. At the very least they hoped artificial hearts could be used to keep people alive while they awaited a donor heart, which were, and are, always in short supply.

Willem Kolff, the Dutch-born inventor of the artificial kidney, was one of the first medical scientists to begin work on an artificial heart. In 1957 Kolff and his team of scientists tested their model in animals to identify problems. In 1969 a team led by Denton Cooley of the Texas Heart Institute used a model they had created to keep a human patient alive for over thirty-six hours. Anticipation grew that the artificial heart, which could potentially save thousands of people each year and would clearly be one of humankind’s greatest achievements, was on the verge of becoming reality.

The first artificial heart implanted in a patient was the known as the Jarvik-7, named after its designer Robert K. Jarvik, an American physician at the University of Utah. Designed to function just like a natural heart, the Jarvik-7 had two pumps (like the ventricles), each with a disk-shaped mechanism that pushed the blood from the inlet valve to the outlet valve. Though the artificial heart mimics the action of the natural heart, there is one crucial difference that cannot be avoided: the natural heart is alive, while the artificial heart is made of plastic, aluminum, and Dacron polyester. As a result, the artificial heart must rely on some external source to “live.”

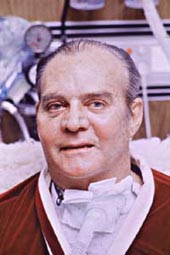

In 1982, William DeVries of the University of Utah, along with a team of experienced assistants, implanted the Jarvik-7 into a patient named Barney Clark. Clark, a dentist from Provo, Utah, was too sick to be eligible for a donated heart; the team decided Clark’s implant would have to be permanent. The procedure was a huge media event. People across the globe counted, undoubtedly along with Clark and his family, each day that the artificial heart continued to function and prolong his life. But though the artificial heart did prolong Clark’s life, it also cost him his freedom. Clark was bound to the washing machine-sized air compressor needed to power the heart. Tubes from the compressor passed through Clark's chest wall, binding him to his bed. Infections were common. Furthermore, Clark's blood clots kept forming as blood passed through the imperfect man-made pump. After suffering a number of strokes, Clark died 112 days after his implantation, much to the sorrow of everyone. Five more artificial hearts were placed in patients through 1985. The longest survivor was William Schroeder, who was supported by the Jarvik-7 for 620 days. By the late 1980s, surgeons at 16 centers, including the Texas Heart Institute, had implanted more than 70 Jarvik-7 devices in patients as a bridge to transplantation.