First-Hand:The D-558-I Skystreak Project - Chapter 4 of the Experimental Research Airplanes and the Sound Barrier

By David L. Boslaugh, CAPT USN, Retired

Design

Now that the X-1 project has pierced the “sound barrier” it is appropriate to go back and review the U.S. Navy’s contribution to high speed flight research. The reader will recall that in March 1944 the Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics had agreed to sponsor a turbojet propelled research airplane to explore transonic flight. The Navy envisioned a three-phase project; the first would be a straight winged transonic research aircraft, the second a swept wing supersonic plane, and the third a prototype fighter based on the test results of the first two airplanes. NACA and the Navy agreed on the following design parameters for the phase I aircraft: [19, pp.61-62]

- It would use the most powerful gas turbine jet engine available, which at the time was the General Electric TG-180.

- The project would use the maximum capacity of the TG-180; that would in theory propel it up to a speed of Mach 1.

- The craft would operate from the ground.

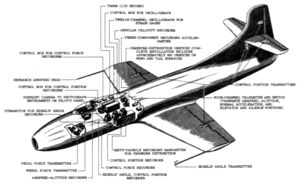

- It would carry 500 pounds of flight instrumentation.

[32, p.5]

The Douglas Aircraft Company of Santa Monica, California, had been a builder of navy airplanes since before World War II, and in late 1944 Douglas engineer L. Eugene Root visited the Bureau of Aeronautics in Washington, D.C. to try to find what areas of aeronautics the Navy was interested in developing next. During Root’s discussion with Bureau officers, Commander Bill Sweeney, in charge of the Bureau’s Fighter Desk, showed Root a preliminary specification they were considering under their agreement with NACA to sponsor a transonic research airplane. Sweeney asked Root if Douglas would be interested in submitting a proposal for such a craft. Root excitedly grabbed the draft and was soon back at Douglas’ El Segundo Division discussing the navy specification with senior Douglas engineers. The company submitted a proposal for six of the planes, and in June 1945 the Navy authorized Douglas to proceed with design. In January 1947 Douglas and the Navy finalized a negotiated contract for the first three aircraft, then nearing completion, with the understanding that the funding for the second three planes would be held for a Phase II airplane of yet unspecified design. [19, pp.63-64]

NACA and the Navy agreed to the distribution of the three phase I airplanes. The first of which would be retained by Douglas and would be fitted with a reduced instrumentation package. This craft would would be used to demonstrate airworthiness to the government, and gather information to support future military aircraft design. The second plane would go to the NACA Muroc Flight Test Unit, and would receive a full instrumentation package similar to the X-1’s. The Flight Test Unit would put the craft through a comprehensive regime of stability and control evaluations, vibration and flutter tests, structure load studies, and wing pressure distribution measurements. The third craft would not be instrumented and would be used mainly for demonstration flights, and ultimately as a spare parts source for the other two planes. [32, pp.28-29]

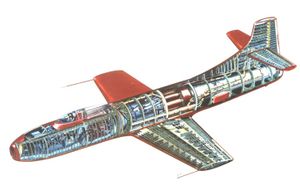

Like the X-1s, the D-558-I was to be built to withstand structural loads up to 18 times the force of gravity, and also the wings would be straight with a relatively thin ten percent chord-to-thickness ratio. In a concession to pilot safety, Douglas engineers considered a pilot ejection seat, but settled on a detachable nose section instead. The back of the section would be open so that the pilot could push himself out rearward to use his personal parachute. Engine intake air would be transferred from the nose scoop via ducts built into the sides of the circular fuselage. The fuselage would be unusually long and thin. The fuselage skin would be made of one tenth-inch magnesium alloy panels, and the wing and tail assemblies would be made of aluminum. The thick fuselage skin would not only make for a very smooth skin surface but would also enhance the plane's structural strength. As in the X-1s, the pilot would have a control yoke in order to be able to apply heavy control forces if needed. The GE-designed TG-180 engine (also known as the Allison J35) would generate 5,000 pounds maximum thrust, 1000 pounds less than the X-1’s Reaction Motors XLR11 rocket engine. [32, p.7, 31]

Skystreak Number 1

In April 1947, D-558-I No. 1 was ready for flight tests and was transported to the secluded “North Base” at Muroc where Douglas test pilot Eugene F. May began his evaluation. On his first few flights the ship was troubled with fuel pressure, landing gear door, and brake problems. By mid July fixes had been found and the No. 1 craft was ready for serious testing. As of early August, May had achieved Mach 0.85 in level flight, and the Number 2 ship had been brought up to Muroc where navy and marine pilots joined in the test program. The Navy was sufficiently impressed with the D-558-Is that it made arrangements with the International Aeronautical Federation to try for a witnessed world airspeed record. On 20 August 1947, navy project pilot Commander Turner Caldwell set a new record of 640.7 mph in the No. 1 ship, but the record only lasted five days when USMC project pilot Major Marion Carl in D-558-I No. 1 bested it by 10 mph. [52, pp.56-57]

The Number 1 ship was then turned back over to Douglas to continue programmed flight tests, resulting in this ship having made 101 flights before delivery to NACA in 1949. The Muroc Flight Test Unit never flew the No. 1 ship, probably due to its paucity of instrumentation, but rather used it for spare parts to support the other two ships. [52, p.57]

Skystreak Number 2

Navy, marine, and Douglas pilots made 27 more flights in the No. 2 craft and then delivered the craft to NACA on 23 October 1947. Gene May continued testing D-558-I No. 3, and in October set a new unofficial speed record of 680 mph. The Skystreak team then thought they were in a neck and neck race with the Army’s X-1 project and were dismayed when they finally learned that Chuck Yeager had actually broken the sound barrier at 700 mph in October. The Muroc Flight Test Unit Instrumentation Section installed a full suite of flight test instrumentation in the No. 2 plane and NACA test pilot Howard Lilly made two November flights before the craft was grounded during the winter for engine maintenance. On 16 February Lilly began a planned program of tests that covered 17 flights. Tragically, on the 17th flight on 3 May 1948, the plane’s engine blew up during takeoff due to compressor failure. Accident investigation revealed that the engine explosion had severed all control cables to the tail surfaces, otherwise Lily might have been able to land the craft. This gave rise to an NACA design requirement for all subsequent research airplanes that control cables near the engine had to have armor protection. [39, p.52] Lilly was too low to bail out, becoming the first NACA pilot to be killed on active duty. The plane was a total loss. [52, p.57]

Skystreak Number 3

Douglas delivered D-558-I No. 3 to Muroc in November 1947, and Douglas test pilots made five demonstration flights before turning the craft over to the Muroc Flight Test Unit . Instead of being used for demonstrations and then as a source of spare parts as originally planned, the Flight Test Unit instrumented the craft for research flights. Number 3 was grounded until April 1949 while awaiting the determination of the cause of the Skystreak No. 2 crash. By 22 April 1949 the cause was known and No. 3, piloted by NACA pilot Robert Champine, took to the air on that day for pilot familiarization and instrument checkout. Seven NACA pilots would then make 77 instrumented research flights until 10 June 1953 when NACA pilot Scott Crossfield made the last D-558-I flight. These flights spawned a number of research reports on transonic flight of great value to the aircraft industry. The D-558-Is never achieved Mach 1 in level flight, but NACA pilot John Griffith did achieve Mach 0.98 on 13 June 1950 in a shallow dive while conducting wing pressure distributution measurements. In total the Skystreaks made 230 flights with No. 1 making 101, No. 2 46, and No. 3 83 flights. The phase III fighter version never materialized because the D-558-I was found too difficult to handle in high speed dives. [32, p 49, pp.52-53, pp.61-62] [52 p.57]