Oral-History:John F. Havard: Difference between revisions

m (→Interview) |

|||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

Now retired, Jack is senior consultant to Raymond Kaiser Engineers and does individual consulting. He continues his long-term commitment to the activities of AIME and SME-AIME, where he has served in many capacities, including SME-AIME president, Henry Krumb lecturer, and chairman of SME-AIME's Industrial Minerals Division. He is the 1982 Hardinge Award recipient, and is one of only two people to have ever received the SME-AIME President's Citation for Significant Individual Contributions to SME-AIME, for his efforts involving construction of the SME-AIME Headquarters building. More recently he has been a member of the AIME After Transition Committee and is chairman of the SME-AIME Long-Range Planning Commission. | Now retired, Jack is senior consultant to Raymond Kaiser Engineers and does individual consulting. He continues his long-term commitment to the activities of AIME and SME-AIME, where he has served in many capacities, including SME-AIME president, Henry Krumb lecturer, and chairman of SME-AIME's Industrial Minerals Division. He is the 1982 Hardinge Award recipient, and is one of only two people to have ever received the SME-AIME President's Citation for Significant Individual Contributions to SME-AIME, for his efforts involving construction of the SME-AIME Headquarters building. More recently he has been a member of the AIME After Transition Committee and is chairman of the SME-AIME Long-Range Planning Commission. | ||

==Further Reading== | |||

[http://www.aimehq.org/programs/archives AIME Oral Histories] | |||

==About the Interview== | ==About the Interview== | ||

Revision as of 13:46, 20 October 2016

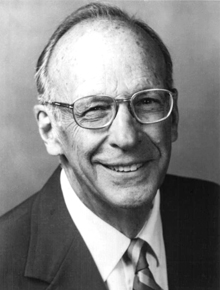

About John F. Havard

Jack Havard started his career in mining and minerals in 1929 as a miner and workman in Montana's lead, zinc and copper operations. He was introduced to mining exploration in the old Rimini Mining District of Montana. After a year at Rimini and a brief period at ASARCO's East Helena smelter, he entered Montana School of Mines at Butte. For three years at Butte he worked in Anaconda's Timber Butte lead-zinc mill, its St. Lawrence mine, in the college library, and also as a reporter for the Montana Standard.

He transferred to the University of Wisconsin at Madison, from which he graduated with honors, obtaining degrees in geology and mining engineering. He went on to graduate school to obtain an Ph.M. in geology and his professional engineering degree. Later he attended Harvard University's Advanced Management Program.

Starting in 1935, Jack spent 17 years with United States Gypsum Company, advancing through operating, engineering and exploration positions to works manager and finally to chief engineer of mines, headquartered in Chicago.

He moved next to Carlsbad, New Mexico with Potash Company of America, responsible for operations of both the underground mine and surface refinery. An offer from former USG associates took him to San Francisco as vice president - manufacturing for Pabco Products, Inc., continuing in that capacity after a merger with Fibreboard Corporation, where he devoted much time to industrial mineral and forest products development. In various combinations of duties, he was responsible for natural resources (principally gypsum deposits and timberland), central engineering, manufacturing, research, labor relations, and purchasing. He was also in charge of building a number of new facilities, such as gypsum crushing and beneficiation plants, gypsum manufacturing plants, asphalt roofing plants, paperboard mills and various packaging plants.

In 1963 he joined Kaiser Engineers as manager of mineral industries projects, organizing the Minerals Division, which provides worldwide services for ferrous, nonferrous, energy and industrial mineral projects. He moved on to become vice president of the Minerals Division and later senior vice president of the company.

Now retired, Jack is senior consultant to Raymond Kaiser Engineers and does individual consulting. He continues his long-term commitment to the activities of AIME and SME-AIME, where he has served in many capacities, including SME-AIME president, Henry Krumb lecturer, and chairman of SME-AIME's Industrial Minerals Division. He is the 1982 Hardinge Award recipient, and is one of only two people to have ever received the SME-AIME President's Citation for Significant Individual Contributions to SME-AIME, for his efforts involving construction of the SME-AIME Headquarters building. More recently he has been a member of the AIME After Transition Committee and is chairman of the SME-AIME Long-Range Planning Commission.

Further Reading

About the Interview

John F. Havard: An Interview conducted by Eleanor Swent in 1991, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1991.

Copyright Statement

All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and John F. Havard dated November 11, 1991. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley.

Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the Regional Oral History Office, 486 Library, University of California, Berkeley 94720, and should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user. The legal agreement with John F. Havard requires that he be notified of the request and allowed thirty days in which to respond.

It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows:

John F. Havard, "Mining Engineer and Executive, 1935 to 1981," an oral history conducted in 1991 by Eleanor Swent, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1992.

Interview Audio File

Interview

INTERVIEWEE: John F. Havard

INTERVIEWER: Eleanor Swent

DATE: 1991

PLACE: Berkeley, California

[Interview 1: September 4, 1991]

Swent:

As a start, perhaps you can tell about your grandfather, your father's father.

Havard:

All right, we'll start with the Havard side.

We have been fortunate in finding old records about the family history. The earliest bits of history describe the Havards as Norwegians --Vikings, if you will. Some Havards had moved to Normandy, where they became involved in the conquest of England in 1066.

Swent:

That sounds like interesting history. What else did you learn?

Havard:

We have copies of extraordinary documents dated 1586 to 1597 in the reign of Elizabeth I. They are so unusual that I believe they should be included in this oral history. One family tree starts with Syr Peter Hafart during the reign of William Ruffus, son of William the Conqueror. It continues until the time of Lawrens Havard in 1591. Some years after the battle of Hastings, Bernard Newmark followed the example of other Norman knights and led a conquering expedition into Wales. To one of his followers, Sir Walter Havard, he gave the castle of Pontwilyn, where the Havards were said to have resided in considerable affluence for many years.

Swent:

Is the castle still in existence?

Havard:

In visiting Wales I found no record of it, but I did find southeast Wales swarming with Havards--a hundred of them listed in two phone books . The name is rare over here .

We do have the family crest, a bull's head with the motto "In Dio Spes Est" or "In God is hope." I have not yet filled the genealogical gap between 1597 and the year of my grandfather's birth, 1846.

My grandfather Havard, whom I never met, was born in the little town of Abergavenny. I visited it and found a beautiful little town with exposed- timber buildings, lovely homes, and of course the ruins of a castle. It is bustling with activity. The town is largely surrounded by lush dairy farms except where it reaches the foothills of the Black Mountains, a national park area.

Incidentally I have four first cousins in Australia. We are especially close to one family, with considerable visiting back and forth over the years .

Swent:

What about the immediate family?

Havard:

My father was born in Australia in the little town of Ipswich, which today is a suburb of Brisbane , and the reason that he was there was that his father had pursued his true love from England to Australia.

A man named Ramm was one of the first railroad contractors and had built railroads in Spain and then was asked to build railroads in Australia, in Queensland. The little town of Ipswich happened to be a convenient place for the various railroads that branched out into Queensland. Mr. Ramm travelled around the Horn from England with his daughter, Mary, to Australia and went about his business of building these railroads.

The story is they had a terrible trip around the Horn in a sailing vessel with a very cruel type of master of the ship, so that it was a very unpleasant experience. But they made it.

Swent:

About what year was this?

Havard:

This was probably about 1869. My grandfather, William Havard, was a young solicitor who had fallen in love with Mary Ramm in England, and he pursued her half the way around the world to Australia, and they were married in Brisbane. I think you can classify that as a true love affair.

And out of that union were born four sons and a daughter, and the youngest member of the family was my father, whose name was Francis Thompson Havard, and as I understand it, he was a normal schoolboy, enjoyed sports, and was educated at the Ipswich Grammar School, which is still in existence and still has quite a reputation around Oceania, or Australasia would probably be more accurate .

Swent:

Francis Thompson was a poet. Was your father named for the poet?

Havard:

I don't know; I doubt it. He came from a good Anglican family, and I am quite sure they would not name him after that Francis Thompson.

My father was educated at the Ipswich Grammar School and was graduated from there. His mother was a rather strong-minded woman who was interested in the careers of her children and decided that metallurgy was a coming field. So the decision was made that he would attend Freiberg, the great technical university in Germany, which at that time was outstanding in the field of mining and metallurgy. And so he entered Freiberg in 1897, so well equipped in German from his Ipswich Grammar School that he could move right into a German technical university and participate as a student. He was graduated from Freiberg in 1901. One of his best friends was an Irishman from the sweet vale of Avoca--Jack Wynne. I was named after him.

Swent:

This was in the Hartz Mountains.

Havard:

On the fringe of the Hartz Mountains in Germany.

His first job was as furnace foreman at the Great Falls Smelter in Montana, and while there he was a young, single man -about -town and was invited to a ball that was held at the Park Hotel in Great Falls, which was a great establishment in those days, by the owners. People were invited from the Butte-Helena-Great Falls Corridor and from elsewhere in the United States. At this ball, my father had a dance with my mother, and there was an immediate attraction. She had been invited to the ball from her home town of Helena.

Swent:

Love at first sight?

Havard:

Right. It was love at first sight, by two highly romantic people, but they didn't get to know each other well enough to become engaged. Shortly thereafter, he was offered work in Germany, and he went back to Germany and operated some mines in the Hartz Mountains for three years, keeping up a correspondence with my mother, which is quite a formal correspondence.

Swent:

Has this been preserved? Do you have those letters?

Havard:

Oh yes, I have those letters.

Swent:

What a treasure.

Havard:

And they are very interesting because of they way they addressed each other in very formal ways, you know. But my mother had made up her mind that that was the man for her. He left then, after the conclusion of his work in Germany, came back to the United States to Helena, and proposed to my mother, who, of course, accepted, and then he went down to Chile to build a copper smelter for the Copiapo Mining and Smelting Company, which issued him, as part of his pay, some stock which I still have and which are interesting pieces of paper. He was down there eighteen months.

Swent:

And this is in what part of Chile?

Havard:

In the northern desert of Atacama.

Swent:

The Atacama Desert- -not a good place to take a bride.

Havard:

No, he originally thought that he might send for her and they would be married down there, but he found the conditions were too rough for her. So at the conclusion of that job, he came back to Montana, and they were married in Helena.

Swent:

This must have been about 1905?

Havard:

In 1908. And the other side of my family, my mother's side, also is full of pioneering incidents. My great-grandfather, whose name was Albert Gallatin Clarke, had a business in Missouri, near St. Joseph, Missouri. His two brothers were officers in the Southern Army, and somebody had to support the family somehow. And of course, Missouri was very badly disturbed by the Civil War and by Quantrell's Raiders, which are famous for their forays into Missouri.

He made up his mind to establish a business in the new gold fields in Montana. So he loaded up a flatboat with mining supplies and various other materials, including some china, and he took this material up in a flatboat to Ft. Benton, Montana, where he hired teams and was taken across country to Virginia City, which was then the center of gold mining. After a few months in Virginia City, he decided he was in the wrong place.

So he moved to Helena, which recently had been called Last Chance Gulch. The reason for the name was that a group of prospectors had been hunting gold through the country and had become very discouraged and had done some panning on Prickly Pear Creek, as it was called, and then gone elsewhere. One night, they had a discussion among themselves and said, "Well, we're not finding a thing. We're going to have to give this trip up. Let's just go back to Prickly Pear Creek and try once more. That will be our last chance." So they went into Last Chance Gulch, and they hit gold. That was the beginning of Helena, Montana.

My great-grandfather heard about it and moved his stock of merchandise to Helena and prospered mightily in merchandising, livestock, and mining.

Swent:

Gallatin is a big name in Montana, and around there. Is this--

Havard:

Oh! That is a separate story. I don't know why he was named after Albert Gallatin, but Albert Gallatin is a figure in United States history who never gets the amount of credit he should get, because he follows people like Adams and Jefferson, and somehow he doesn't get attention. But he was a young Swiss who came over here to the state of Pennsylvania and was elected to Congress and later had a life of great distinction, including being secretary of the treasury, and was part of the team that negotiated the end of the War of 1812. And he was ambassador to France. For some reason or other, his name became widespread in Montana, and I have never been able to see the connection, but there are rivers and mountains, and a county, and an airport named after him.

Swent:

But your grandfather's name, you think, was independent of this?

Havard:

I think my grandfather's parents must have had an admiration for Albert Gallatin, who was contemporary.

Swent:

But they weren't related, that you know of.

Havard:

Not that we know of. There may have been an acquaintanceship or something. We don't know. At least, I can't find any record on it.

Swent:

It's a very distinguished name to have.

Havard:

Well, Albert Gallatin was a very interesting man. One title sometimes given to him is that he is the Father of American Ethnology, because he had a great interest in the natives and their practices, along with all the other things he did.

Swent:

But your Albert Gallatin Clarke was known as "China" Clarke.

Havard:

He was known as China Clarke because of the dishes that he brought along, and that name lasted all his life, even though he was a very distinguished- looking man and very dignified. Nevertheless, he couldn't escape that nickname.

Swent:

And he became very wealthy.

Havard:

He became very wealthy, not only in his store, but in cattle and mining and so on. As soon as he was settled, he asked his daughter and her husband, who had just been married, to come out and join him. So they got on the Central Pacific Railroad, which had just been built, got off at Ogden, and then travelled five days by stagecoach from Ogden north to Helena, where they settled down, and the firm of Raleigh and Clarke was formed. My grandfather's name was William Raleigh. They both, China Clarke and my grandfather, built mansions in the style that were built in those days. It was rather interesting that in Great Falls and Helena and in Butte, many of the business and professional people were Southerners, and they all tended to know each other, and they had a great social life- -built these big mansions and put on big parties. And it seems strange nowadays to think of them, these little towns, but it was the Southern tradition.

And another interesting sidelight is that Helena, of course, was on the mainline of the Northern Pacific, and the train ride from Chicago to the West Coast was quite long, and various celebrities would stop off in Helena, particularly artists, because Helena had a nice theater. I know that Madam Schumann -He ink, a great soprano, and Carrie Jacobs Bond, who wrote many popular songs , were both guests in my grandparents ' house . It was a rather interesting community of people.

Swent:

And it's now the capital.

Havard:

Yes, as a result of a great political struggle, which in itself is a fascinating story that reflects the great rivalry between the [Senator W.A. ] Clark interests and the Anaconda Company's interests. Marcus Daly wanted the capital to be in Anaconda, which was his town, and Clark fought it fiercely, and in the end the people voted for Helena. That was not an easy choice.

Swent:

Was it already the capital when your family was there? No, of course, it wouldn't have been. Not when your great grandfather came. So they must have been involved in that.

Havard:

They had certainly voted for it as the capital.

Swent:

Was your family involved in the politics of the state?

Havard:

Very little. Apparently, China Clarke was not interested in politics and was not interested in being in the public scene very much. He was a bank director, and that sort of thing, but his name does not appear in the politics at all. I think he avoided that political scene. Anyway, there were pioneers on both sides of my family.

Swent:

And this ball was part of the Southern social life?

Havard:

Right.

Swent:

So then your father came back, and your parents were married there in Helena.

Havard:

In Helena. And then my father engaged in various consulting work, mining and metallurgy, around the state. Then I appeared on the scene. I was born March 15, 1909. And I was born in my mother's own bedroom in the big house she was brought up in, because the nursery at the hospital had an infection loose in it, and they didn't want me to go to the hospital.

Swent:

Of course, in those days a lot of children were born at home anyway .

Havard:

Yes, I imagine. So after I arrived in the scene, my father decided he should stop roaming and try to find a position where he could be stable and help bring up his little boy. He was offered a position starting the Metallurgy Department at the University of Wisconsin and took it, and we moved to Madison, I would assume in 1910.

Swent:

Do you have any idea how he happened to be called to Wisconsin?

Havard:

I don't know. I don't know what the contact was.

Swent:

He must have had connections of some sort.

Havard:

He had made many influential friends in New York and places like that in his work, so I suspect that one of these probably spoke up for him. He enjoyed his work very much, and while he was there he wrote what was for many years the standard textbook on refractories, called Refractories and Furnaces . Shortly after he completed that book, he got pneumonia, and he died in the hospital, because in those days it was a gamble. Either you lived or died if you got pneumonia. And he was a healthy, athletic, young man, but it took him.

Swent:

How old was he?

Havard:

Thirty -four. And I was four.

Swent:

Terrible. So there was your mother in Madison, Wisconsin, with no family around.

Havard:

Well, in the meantime, my mother's family fortunes had disappeared, literally, and so we had royalties from the book and small life insurance payments to live on. My mother was very restless, so we moved around the West a great deal.

Swent:

Where did you start school?

Havard:

I started school in Helena, Montana.

Swent:

She went back there first.

Havard:

I wound up graduating from Stadium High School in Tacoma, Washington, which fortunately was an excellent high school.

Swent:

Did you have relatives in Tacoma?

Havard:

No. We had a friend there that wanted a house looked after while she travelled, and that's why I went there.

Swent:

So you had a place to live anyway.

Havard:

Yes, for a year.

Swent:

But your mother was not very strong.

Havard:

Well, she was physically strong, but she was disturbed mentally. The term they used- -she was nervous. Well, she had more profound problems than nervousness and couldn't possibly hold a job or anything like that. So I was brought up really as a poor boy, but she always had an interest in finding some little place to live in a good neighborhood. So I always got to good schools.

Swent:

You must have had a lot of responsibility.

Havard:

Yes, I sorted of started taking care of her when I was four, in a way. It's not really true, but partly true.

Swent:

You had to grow up very, very young, I'm sure.

Havard:

Stadium High School in Tacoma was an extraordinary experience, and I look back on it now, with all the troubles they have in high schools , and think of that place , where you never had to worry about anything ever being stolen, where you never had to worry about drugs or liquor, where there was so much activity for people to do after school. You know, athletic teams and girls' athletic teams, and clubs of all kinds.

The biggest impression made upon me was by a man who taught journalism, which is sort of an unusual high school course. His name was Ural Hoffman, and I'll never forget him. He not only taught journalism, but he taught us really, basically, how to write English. So we put out a weekly newspaper of which I became editor, and it was just a great high school experience. And a total contrast with the problems we hear about today. No girl ever got pregnant. You know, just a different world.

Swent:

How many were in the high school? Was it a big school?

Havard:

It was a big school, about 1800. Senior high school.

Swent:

And your English and writing training has certainly stood you in good stead ever since, hasn't it?

Havard:

Yes, it certainly has.

Swent:

In fact, I think you said at that time you hoped to become a journalist.

Havard:

Well, this man got me so interested in it, I expected to make a career of journalism. And he expected me to make a career of journalism.

Havard:

At that time, my mother and I were absolutely running out of money. There wasn't any left. And just at the right time I got a job writing what we called "radio continuities" for a Seattle radio station. The client was Sperry Flour Company, which has long since been absorbed by somebody, and I had to write a program for every evening, five days a week, which meant that every day I had to complete a program. I started soon before I finished high school. I doubled up the end of high school and the beginning of this job.

Swent:

What sort of program was it?

Havard:

Well, I wrote travelogues, if you can imagine. And I wrote to every Chamber of Commerce where I could get information, and wrote these things. And then there was a man and a woman who provided the music, and that was it. Prime time. Six- thirty in the evening. Radio was pretty crude in those days.

Swent:

Did you do the speaking, as well?

Havard:

No, I just wrote it. Meanwhile, I registered at the University of Washington in journalism. And when the contract had expired for that particular program, of course, I was out of work, so I began to hunt for work, in Seattle particularly, so I could go to the University of Washington. And I was unsuccessful.

Havard:

I think that the Depression was not too far away, and it was very difficult to find anything. I had a cousin who was starting a new mining venture in Montana who wrote to me and asked me if I would like to come and work for him. I had no alternative. I said, "Certainly." So I went back to Helena.

Swent:

What was your cousin's name?

Havard:

His name was Phil Barbour, and his partner, who had the money, was Norman Slade, who was the grandson of Jim Hill, the railroad builder. I think that my cousin's first idea was that I was to be kind of a staff man for him and work on claims in the courthouse, and do that sort of thing, but he quickly ran out of that kind of work and sent me up to the mine to work as a laborer. The mine was about seventeen miles from Helena, up near the Continental Divide, in a famous, little old mining town called Rimini [rhymes with "eye"] which, of course, should be pronounced Rimini [rhymes with "me"] and was probably named after some travelling show that stopped in Helena.

Swent:

What were they mining?

Havard:

Well, my cousin had a great interest in mining, and his father was a physician whose hobby was grubstaking miners who had something that looked good up in the mountains. And Phil had gotten some training by following that.

His reasoning was that the great Butte camp was at the southern end of the Boulder Batholith and that Rimini, an old mining camp, was at the north end of the Boulder Batholith, and that Butte had started with gold, silver, and lead mines near the surface, with the copper discovered deeper, and Red Mountain at Rimini had only been mined surficially for lead, silver, and gold. His thought was that maybe there was another Butte looming there. So he was going to drive a crosscut adit or tunnel deep into the bowels of Red Mountain to see if he could hit a situation parallel to Butte, which wasn't such a bad idea.

So by the time I got there, this adit had just been started, and I went to work, first outside as a laborer, and discovered that I was in terrible physical condition to do that kind of hard work. I had worked before in factories and whatnot in the summertime, but I had never been up against a pick and shovel and the kind of work I had to do there. But I did it. I persisted and did it.

Swent:

Where were you living?

Havard:

Well, we were able to rent a little cottage. My mother was with me. We rented a little cottage in Rimini, and in the summertime this little cottage had running water from the stream, and in the wintertime every morning I would take an ax and two buckets and go off and break the ice in a nearby horse trough and fill the buckets of water and bring them back, and that was the water for the day. The result was that we didn't bathe very often. I didn't [laughter]! Once a week I bathed in a tub in the kitchen. Anyway, and when it's the wintertime --

Swent:

What did you burn for heat and fuel?

Havard:

Wood, which was delivered as cord wood and which I had to saw and split by hand every day, to have ready for the woodstove. We had a little stage which was a Ford- -kind of a station wagon of that day- -driven by a young farmer who did the shopping in Helena for the citizens of Rimini and brought the mail and the food up to the camp for us .

Swent:

You gave him your list, and he picked it up.

Havard:

He had great pride in getting through, and if the snow got deep, he'd come through with a team and a sled, but he'd get there one way or another [laughter]. And kept us alive.

Swent:

You were working six days a week, seven days a week?

Havard:

I can't remember; it must have been at least six. I think it was six, because I did have a girl friend, and I mean just a friend, in Helena, and on occasional Saturday nights I hooked a ride to town and would take her to the movie and stay overnight with relatives and come on back, and so on. It must have been a six-day proposition.

Swent:

What was there at Rimini? Just a few houses?

Havard: Well, it was a typical movie set. You had the dirt road following the creek, you know, up into the mountains, and the little town was spread along the road, with one little side street with a few little cabins on it. And the town at one time had been quite prosperous and had a number of businesses, all of which were log cabins with false fronts. Typical. Just exactly what you would see in movies. And there were no stores or anything up there. The only commercial establishment was Mrs. Wilson's boardinghouse, where the single miners ate very well indeed.

Havard:

After working as a laborer, I began to get more responsible jobs, and this leads me to tell you about Ethel. Ethel was a mule. We had been hand- tramming the cars out of the tunnel, and I had done quite a bit of that. I mean, just to push the empty car in, and ride and push the loaded car out to the dump and spill the contents. But we were getting too far back for a one-man hand-trammer to keep up, so Phil hired Ethel and Ethel's mule skinner. Ethel's mule skinner was named Shorty. He was really short, probably about four feet tall, and had the map of Ireland on his ruddy face. He and Ethel were a pair and loved each other, and I will never forget the day they came into Rimini, and he drove Ethel with great dignity up the main street to her stable. I should mention that Shorty's unvarying lunch was a pancake sandwich- -a pancake between two pieces of bread.

And of course, he was her mule skinner underground, and I think she handled three or four cars at a time and knew her business and had done it elsewhere. I think he probably served both shifts, because mucking was only half the shift, you know. But he was afflicted with prosperity and had saved his money. He disappeared, and I was led to understand that this was normal procedure. That after he had accumulated a certain amount of wages, he would go to some town and blow it, you know, drink it away. Anyway, he was gone six weeks on this big bash, and I was appointed the mule skinner. So, Ethel and I--

Swent:

Oh, he didn't take Ethel with him?

Havard:

No, no. He left Ethel behind, and I skinned Ethel. I learned how to be a mule skinner, but I didn't have to learn much because Ethel knew more about it than I did [laughter] and behaved herself perfectly until the last night when I put her in her stable, and she expressed her contempt for me by lashing out at me with both her rear hooves and fortunately missed me. But I thought, all right, she realized that she had had a lousy skinner for six weeks, and she was going to show me.

So then I was promoted to run the compressor and do all the outside work on the night shift. This compressor was a mechanical marvel by today's standards. It was a Chicago Pneumatic semi-diesel engine and compressor, the like of which, fortunately, we no longer have to put up with. The semi-diesel engine meant that it worked under lower pressures than a normal diesel engine. You started it by putting a blowtorch on a hot tube in the head of the engine, got that tube cherry red, and then you would hit the machine with the compressed air from the tank where you kept the compressed air stored, and kicked it over, and it would start running. And it ran along all right, compressing air with its very inefficient engine, and it would burp little circles up above the smokestack.

The problem with this engine was that once a month it had to be taken down and cleaned. And so I would stay over (the shift would end about three o'clock in the morning), and the master mechanic would come up, and we would tear the engine down and become absolutely filthy with grease in the process, clean the engine up, and put it back together again.

Swent:

It burned diesel?

Havard:

It burned diesel fuel.

Swent:

Where did you get that?

Havard:

Oh, I think that was brought up in barrels, inefficient machine.

Swent:

Why was it called "semi-diesel?"

It was a very

Havard:

Because it didn't have the compression that it takes to be a full diesel engine, you know. You had to start it by getting this tube cherry red and then kick it with the air. And the tube would stay hot, and it was only a partial diesel. It was very soon superseded by the full diesels. You know, it was an anachronism.

Swent:

What did you use the compressed air for?

Havard:

Well, that was used in a normal fashion underground. We had a pipeline into the mine. The miners were very skilled, and they were equipped with the big heavy Ingersoll-Rand drifters, and they used a crossbar to mount the drifter on, which is a practice that is now obsolete. The muck was hand-mucked off the turn sheets (steel sheets) and into the cars.

After the muck was shovelled off the turn sheets, the tough part was mucking on the rough, as they would say, where your blast had taken place, and, of course, where you had no turn sheets. I would always go in at that time and help them muck off the rough. You used a round-point shovel, and that was hard work because there was no steel sheet. You were just digging into the pile of broken rock. Then after that was done, the machine was set up again and the lifters of bottom holes were drilled, with the drill underslung on the bar.

Swent:

Were these jackleg drills?

Havard:

No, no, no. These are not jacklegs. Before jacklegs. This was a big, heavy, horizontal bar that had a screw on one end of it. And you would mount this lifter (which was a quite a heavy machine, all I could do to lift it) , and you would drill your holes off the horizontal bar, and that could be done while the muckers were working on the turn sheet. And everybody had a turn to get the muck off the rough. Then you would put the machine down underneath the bar and drill the lifters. All of this was an excellent education for me.

It was also up to me to prepare the explosives for the night.

Swent:

What kind of explosives?

Havard:

Well, we used real gelatin dynamite, potent stuff, and we used number-eight caps and fuse. The rock was hard, so we used the real gelatin dynamite.

Swent:

You had to be really careful with it.

Havard:

Yeah, we had to be careful with it. I'll never forget one night. I would get everything together and put it into an empty muck car, and it would be taken back in. And there would be a box or so of dynamite in the bottom, and then the primers would be on top where the caps were inserted into the dynamite. And one night the muckers didn't look. They started mucking right into that car, and discovered to their horror that they were throwing rock on top of those primers [laughter] .

That's as close as we ever came to having a real disaster. Never had much in the way of accidents because the men were good, you know. We didn't have a lot of safety rules printed around. We just had people who knew what they were doing. And taught me how things should be done. I was a very willing learner. Fascinating experience for me. There are lots of stories that go with Rimini --too long to put into this.

Swent:

Oh, no. Tell some more.

Havard:

Well, one more story. Before I was promoted to my responsible night-shift job, I spent several months in the morning striking steel for the blacksmith. He was a big wonderful man, maybe 6' 5" and fit. This was before detachable bits came into use. The bits were an integral part of the drill steel, which of course came in various lengths. The blacksmith had a synchronized program of heating the bits in a forge, shaping them while red hot, and then tempering them just right in a water bath. Well, my job was in the shaping, first swinging a twelve -pound sledge against the die which the blacksmith held against the red-hot dull bit and then finishing the job by tapping a sharper die with a light hammer. My chief objective was not to hit the blacksmith's hands! I did-- on my first day. He just looked down on me, not saying a word, just looked down on me. I never hit his hand again. In time I developed a modest degree of skill and a considerable degree of new muscle. I loved this job --the huge, genial blacksmith, the red-hot steel, the sizzling water, the smell of the forge, the taste of sweat- -you know, a fun scene for an impressionable youngster.

In those days I could step back and look at a whole scene, and the scenes around that mine trapped me into a romance with mining which has never left me .

Swent:

That picture explains a lot.

Havard:

The end of it was that after I had left they kept going until they were in there I think 3300 feet, and while they hit veins, they never hit a commercial vein, so the venture was a failure, unfortunately .

Swent:

Did they get the costs out at all?

Havard:

No.

Swent:

Nothing. What a shame.

Havard:

No, they never developed any ore. They did hit the veins. The veins were there. They were not copper-bearing, so it was not a successful venture. But I was gone.

Swent:

I think you said along in there somewhere you also got a letter from the newspaper in Seattle.

Havard:

Well, just after I got on the job, the newspaper in Seattle wrote me that I had the job as university reporter, but it was too late.

Swent:

You were a miner by then.

Havard:

Well, I was a laborer by then [laughter]. Learning how to do hard work. Well, anyway, partway through this, it must have been early spring of 1929 that Phil ran out of money for a while, and I rustled a job at the East Helena Lead Smelter of American Smelting and Refining Company.

I hadn't mentioned this before. It's interesting that I was given a physical examination before I went to work in the smelter- -this was 1929 --and the doctor gave me very clear instructions on how I was to handle myself from a health standpoint, that I was to always wash my hands before I ate, that I was to drink lots of milk while I was on the job, and I was to wear a dust collector if there was any chance of any dust. So the company at that time was aware of the hazards of lead and were instructing their new employees on how to handle themselves. Actually, they didn't know how really deadly it was in terms of dust that you don't see in the air. But at any rate, there was a real good examination and real good instructions to the best of their knowledge at that time.

And my job was to run three Dwight-Lloyd roasters. These were standard grate roasters that were used in the metallurgical industry, and I think we had a bank of eight of them. They were small machines by today's standards, and I had to run three of them. I think it was probably the worst job I ever had in my life, because it was so dull. Most of the time, you just walked up and down, up and down, watching these machines, you know, and looking at the feed that was going onto them. But if anything went wrong, then all hell broke loose.

Swent:

What sorts of things went wrong?

Havard:

Well, I don't remember. A chain would probably break or something, and the machine would shut down. The foreman would come running, and the mechanics would come running, and it would be a frantic scene. But shift after shift, it was just as dull as it could be.

Swent:

Nothing went wrong.

Havard:

Nothing went wrong. You just walked up and down on this bank of roasters. Those machines have all been taken out and replaced by one modern machine. But the mine reopened, and I left the smelter and went back up to the mine.

I was only at the smelter one month, then I went back up to the mine and renewed my work up there.

Swent:

They were still trying to mine?

Havard:

Yes, they got their finances together and reopened. I went back up, and I made a trip over to Butte to see if I could enter the Montana School of Mines. By this time, I had become fascinated with the mining business as I observed it. And I was exposed to one of the most interesting situations you can get in, which is exploration, where day-to-day you are always looking for something remarkable to happen. I found out that I could get in there [at Montana School of Mines], and I think I had saved up three hundred dollars , which was enough to make the move .

Swent:

You haven't said how much you were paid for your work at Rimini.

Havard:

I was paid five dollars a day.

Swent:

As a laborer. And were there any benefits?

Havard:

Oh, no. You took care of yourself.

Swent:

And you were still able to save?

Havard:

I think I saved three hundred dollars, and that was enough to move.

Swent:

And you were supporting your mother, as well?

Havard:

Oh, yes. All of the time. Of course, our expenses up there were not very high.

Swent:

Well, you had to buy your own work clothes.

Havard:

Yes, and I think our rent was something like fifteen dollars a month .

Swent:

Did they have hard hats yet?

Havard:

No. I should mention that. The hats were soft, cotton hats, and we used carbide lights. Safety shoes were not in use. So that, really, there was no safety equipment.

Swent:

What sort of clothes did you wear? Blue jeans? Denim?

Havard:

No, just brown work clothes, and in the wintertime you wore warm underwear and layers of clothes, winding up with a sheepskin coat, if you were outside.

Swent:

Was it wet underground?

Havard:

Yes, it was wet underground, at times. If it was wet, we just put on slickers. I would finish up, when I was running the compressor and doing outside work, somewhere around three o'clock in the morning, and then I would have to walk a mile down the road back to town by myself, because it was my job to start up the ventilating fan and blow the powder smoke out, do the last chores, and then walk home, about three or four o'clock in the morning. And, if it was cold, then I had a big sheepskin coat that would keep me warm.

Swent:

So the mine was working two shifts?

Havard:

Two shifts, yes.

Swent:

And you were really working both shifts?

Havard:

When I was running the compressor and doing the outside work and going in and helping in the mine occasionally, that was all on the night shift.

Havard:

And in spite of all that, you still liked it?

Havard:

Oh, I loved it. It was fascinating. Well, I went over to Butte, and we rented a little, tiny, tiny house not far from the Montana School of Mines, and I started job hunting.

And I was very fortunate, because without much looking, I got a job as a laborer at the Timber Butte Mill, which was south of Butte, and was a rather noted flotation plant because of the new processes which had been developed there. My job was simply doing whatever labor the crew was required to do. This was afternoon shift. The first thing we had to do was to unload the incoming ore cars, which were bottom-dump hopper cars of about fifty tons capacity. We had to unload them into the big receiving bins and then get up and clean them out.

And then in our spare time, one of the most fascinating jobs was shovelling lead concentrates into a boxcar. Lead concentrates are heavy, as you might guess, and they are sticky. And so you used an oiled, square -point shovel so that when you threw the lead concentrates towards the back of the boxcar, you wouldn't follow them [laughter], and that was pretty good exercise.

Swent:

Was there any hazard involved in this?

Havard:

No, I don't think so. They were damp. By today's standards, they were probably hazardous; but by those standards, they were damp, and there wasn't much dust in the air. Then there was ordinary cleanup work and so on that kept us busy.

Swent:

How much were you paid for this?

Havard:

This was five dollars a day. I think I worked six or seven days a week; I can't remember which.

Then I signed up for about two -thirds of a load of courses at Montana School of Mines , and I had my troubles because , while I had taken a full amount of high school mathematics , I really wasn't prepared for engineering school mathematics. So I had to work pretty hard at that. I gradually began to fall behind, and I couldn't keep up the full shift of labor, and I couldn't keep up the number of courses I was trying to carry, about a two -thirds load. I was short of sleep, too.

I was just getting worn out, and two things happened. I asked the foreman if I could come to work at five o'clock instead of three in the afternoon on school days, and that suited him just fine, because that was really the time when the cars were spotted for unloading.

Then I had a very fortunate incident take place at the school, where the teacher of freshman English invited me into his office one day and told me that he wanted me to leave the regular class, and he wanted to tutor me. I think it was two or three times a week in the afternoon that he would tutor me . And so with that combination of changes, my life got much better for me.

Swent:

Got a little more sleep?

Havard:

Yes. And he had me do creative writing.

Swent:

Do you remember his name?

Havard:

His name was Johnson, and I do not remember his first name. He had a master's degree from the University of Minnesota, and I think this was his first college teaching job.

Anyway, out of that came a story called "Night Shift" which recounted my experiences at Rimini, in a third-person type of way, and it was picked up by a regional magazine called The Frontier. And then, to my utter amazement, it was listed as one of the best short stories of that year in the O'Brien Best Short Stories. And it has been reprinted as part of an anthology on Montana, a book. And so that tutoring was very well worthwhile.

Swent:

What about some of the people that you met there? Did you make any friends that you have kept?

Havard:

Certainly, there were some friends that I have kept. We went very divergent ways, because I left there before I even graduated, but there were a few people I stayed close to for years , particularly a very fine man named Ralph Utt, a fellow student of mine, who was later vice president of Western Knapp Engineering, before it was sold, in San Francisco.

Swent:

That's Davy McKee now?

Havard:

Yes.

Swent:

Any others that you would like to mention?

Havard:

Well, he was the chief one. As I say, the problem was I left before I graduated. I did about two years' work in the three years I was there.

Swent:

And you were working at the Timber Butte mill?

Havard:

Well, I worked at the Timber Butte mill starting in the early fall of 1929, and I worked until the summer of 1930, when I was laid off, and shortly thereafter the mill was shut down and never started again. There is nothing there now but concrete ruins.

Swent:

Who had done the flotation work there?

Havard:

The mill was a Clark mill. It was built by the Clark interests, not by Anaconda. But when I worked there, it was an Anaconda mill. Everything was Anaconda. A man named Griswold was the chief metallurgist, and with a partner named Sheridan was responsible of the success of the process at the mill. Selective flotation was developed to a high degree there, because it was a lead-zinc mill, and the use of cyanide in selective flotation was pioneered there. And all of this was Greek to me; I was just looking at hand shovels.

I walked to the mill one afternoon with Mr. Griswold, and he learned that I was a student at college. He lent me some books and was just as nice as he could possibly be.

Swent:

You had talked about the Timber Butte Mill. I guess you worked there until it closed?

Havard:

Well, no, I was laid off shortly before it closed.

Swent:

Laid off because it was closing?

Havard: Yes, because the Depression was putting the clamps on it, and it was unprofitable. Shortly after I left, it did close permanently.

Swent:

You had several other jobs during your three years in Butte.

Havard:

Yes, I certainly did.

Swent:

At one point, I think you said you had four outside jobs?

Havard:

All four at one time, in the school year of 1930-1931, if I can count right.

Swent:

In addition to going to school, almost full time. What were they?

Havard:

Well, when I was out of work from the Timber Butte Mill, I had looked, of course, for something to do, and I landed a job in moving the library at the Montana School of Mines from the second floor of one building to the main floor of another building, where it had more room.

And I worked for a librarian who was a very interesting woman, and who became a significant part my life. Her name was-- she had just been hiredMargery Bedinger. She was a graduate of Radcliffe and very competent. It was remarkable that we got her at that little school. She had just been librarian at West Point, and she did not like West Point. She wrote an article for, I think, the Nation magazine entitled, "The Goose Step at West Point," with a lot of criticism of the way they did things in those days, probably pretty well-deserved criticism. Anyway, she left West Point and came to us. She hired me and a couple of other students to help move this library. The job occupied me all of the summer, and it was quite a job, physical as well as carrying a lot of elements of learning about the library business, and the Library of Congress system of notation and all that sort of thing.

Swent:

She was teaching you about that at the same time?

Havard:

Well, she had to, you know. We moved the books from this one building down to this other building, and in the course of this, of course, I got to know her very well, and we became lifelong friends. She corresponded with me up until the time she died.

Then I also got a job writing public relations news stories for the School of Mines that were sent to the newspapers around the state, telling of events going on at the School of Mines. And I guess those things kept me busy then. This was the first summer between my first and second year.

One of the interesting things about Margery was that she was an early expert on Navajo jewelry, and in the twenties she rode horseback deep into Navajo country and collected. Eventually, she wrote a book on Indian jewelry, which was sort of a standard work on the subject. So she was a very interesting woman to be around, an extremely bright and stimulating person to be around.

Swent:

Quite a little older than you?

Havard:

She was about thirty -five when she came there.

Swent:

You probably thought she was an old lady.

Havard:

No, no. She later went on to other places. Also she brought with her a lot of world travelling as well as her Radcliffe education. So those of us who were privileged to work with her received quite an informal education in other things.

Swent:

She talked about her travels?

Havard:

Oh yes. Then the second school year came along, and I remained in the library as sort of an assistant, and I continued to write the PR news for the school, but then I also got a very interesting and unusual job.

This was the Depression. The School of Mines was short of money, and the English instructor that I had liked so much, and who was so kind to me in the first year, had left, and they were unable to replace him because of finances. So Professor Scott, who ran the English and economics departments of this college, was overworked. He knew of my background, so he asked me to correct the English freshman themes, and I did that for the whole school year. It was probably totally illegal, because I was a sophomore myself. But I had done so much writing and newspaper work that he was pleased with the results.

Swent:

Did he pay you something?

Havard:

Oh , sure .

Swent:

English and economics is kind of an unusual combination, isn't it?

Havard:

Well, it was a small school. He taught the humanities. The most interesting incident in that work was that in going over the English themes one week, I discovered two themes that were identical, word for word, and they were written by people I knew. And so my quandary was what to do with these themes. I decided I would correct them in the same mode in which they were written. I made identical corrections throughout the two, gave them identical grades, made identical comments on the two of them, and sent the whole batch to the professor. Of course, he didn't look at them in any detail, and he didn't catch it, but the two fellows caught it. I never had any more duplications from them. I don't know if maybe I'll go to jail yet for having done that, for correcting freshman English themes as a sophomore.

Swent:

Were there women in the classes?

Havard:

There were a few women. They were taking general courses. I don't remember any women yet in engineering at Montana Mines, but women were there, treating it as a junior college for a couple of years .

And the fourth job was that I worked weekends in the St. Lawrence Mine in Butte, which was one of the oldest and smallest and shabbiest of all the Anaconda Company's mines. The company had made the practice for many years of hiring students from the college on weekends and giving them jobs underground, filling in for miners that were off for one reason or another. This was a great thing, and many of the boys existed on the money that they made, which was something like five dollars a day. But some of the students who were really physically tough and knew their stuff worked as contract miners, and they made twice as much. But I wasn't that type.

For anyone who was interested in mine design, this mine had one peculiarity that set it aside. It was on such a steep part of the Butte hill that they couldn't use a conventional hoist with cable because the hoist had to be so close to the collar of the mine that there wasn't room for cable to move back and forth across the drum, so they used a braided steel cable that wound up in one layer on a narrow drum, and there were very few such operations anywhere.

Swent:

They had to invent that there?

Havard:

Well, this had been done elsewhere on steep hillsides where they couldn't get the fleet angle that was required for a conventional cable hoist where it moves back and forth across the drum. This one just wound up on a spool. And also the cages and the skips didn't fit very well in the guides and would sometimes get stuck. It was a strange mine.

Swent:

Was it safe?

Havard:

Well, I never did see an accident in that mine, but there was no formal attention paid to safety. For instance, the first night I went to work, I just went down to work, was handed over to some miner to help him, and there was no safety instruction of any kind. You were on your own and dependent upon an experienced miner to keep you safe. We were still wearing soft cloth hats and using carbide lights. There was little advancement in safety.

The same kind of air tools that we had used up at Rimini were being used in Butte, the Ingersoll-Rand, or some brand of big drifters, and what we called "buzzies" (they were known either as "buzzies" or "widow makers") that drilled up -holes, and jackhammers for down-holes. And there were compressed-air mucking machines introduced and storage-battery locomotives, there most of the school year, two nights a week.

So I worked

Swent:

I suppose Anaconda pretty much ran the college as well as everything else, did they?

Havard:

Well, it wasn't visible, but you can bet that the president was very sure to be good friends with the top people at Anaconda, because Anaconda was really pretty much running the state at that time.

And I also took a little time off to play football with the team [laughter] . We had considerable success among the small northern Rockies colleges, and we played in all kinds of winter weather. I certainly kept myself fully occupied and learned how to use time . I never was one of those tough guys that could go without sleep or rest. I had to schedule my life all right.

I got through the second year, and then along came the second summer in Butte, the glimmer between the second and third years, and I asked for a job at The Montana Standard, which was the leading newspaper in the area at that time, and they hired me as a cub reporter. They were sort of familiar with what I had been doing because stories that I had been writing for the school, of course, had come to them. They hired me, and I worked full-time all summer, taking the place of reporters going on vacation, so I was exposed to everything.

When I first went on the police beat, I was introduced to the chief of police of Butte, who was known as "Jerry the Wise." Jerry was an enormous Irishman with a florid face and purple nose, and two of the sharpest, coldest, blue eyes I ever saw in my life. He fixed his gaze on me with those two eyes and said, "Jack, you understand that there are some things which we do not write about?"

And I was in no mood to defend freedom of the press at that time, so I agreed with him [laughs]. But no incident ever occurred while I worked there when that dictate had to be brought into the picture. Jerry the Wise kept order in that whole community of fifty thousand people with two uniformed policemen, and I am sure, and I could never prove, that he had an army of informants, because the town was kept under control. There wasn't any question about it.

Swent:

And not necessarily a docile population either?

Havard:

No, no. The Depression was on, but people hadn't really started

to leave, so there probably were close to fifty thousand people in the general metropolitan Butte area.

Swent:

There was a big Irish population there, wasn't there?

Havard:

Yes, there were a lot of Irishmen, and there was quite a lot of segregation of mines by races. For instance, the Irishmen lived in Dublin Gulch, and many of them worked in the Mountain Con Mine. And, the Mexicans lived down in the Flat, and they all worked in the Belmont Mine, which was the hottest mine in the camp. There was a tendency for Finns and other nationalities to segregate by mines, probably not as much as is represented by the conditions at the Mountain Con and the Belmont.

Swent:

What were conditions like at the St. Lawrence?

Havard:

It was a small mine, a mixed group of people.

Swent:

Was it awfully wet or hot?

Havard:

No, because it was a shallow mine, it was fairly cool. The deeper mines were hot, and the Belmont was notoriously hot, where the Mexicans worked.

Swent:

I have heard stories of some of them being so wet and dripping acid?

Havard:

Oh, yes. The waters were very acidic in some parts of the

mines. In later years, those acid waters were pumped to the surface and spread across launders filled with scrap iron, and copper was recovered.

Swent:

So you didn't have to report anything that you felt a problem with?

Havard:

Well, I think I had just one experience where I ran into the Anaconda Company, and that was in the summertime when part of a schoolyard caved into an old mine. They had stopped near the surface, and one summer afternoon there was a cave-in and no children standing where the cave- in took place, fortunately. And I was Johnny -on -the -spot. And in no time at all, their trucks were running in there with fill. I had a story, but I couldn't print it, which was rather stupid because everybody in town knew it had happened.

Swent:

Were you told not to print it?

Havard:

Well, the story was just killed.

Swent:

The editor just didn't print it.

Havard:

I don't think I even got to the point of writing it. I just came back in with my notes, and he said, "Don't bother writing it."

Swent:

What was the labor situation like then?

Havard:

Well, it was thoroughly non-union. There never was a story of any accidents in the mine, and men were being killed from time to time, but no story would ever appear in the paper. The company maintained a pretty good hospital called Miner's Hospital. And then there was a Catholic hospital in the town, too, and I used to visit them both when I was on the police route and see what was going on.

Swent:

When people were laid off, did they just have to leave Butte?

Havard:

Well, really the only thing they could do was to get out of Butte, try to get wherever they came from, to their home or some place.

Swent:

Did the company own housing?

Havard:

No. The company had a big department store, but it didn't meet the "company store" stories at all. It was just there, and you could use it or not, if you wanted to. No, there was no interference in the private lives of the miners at all.

Swent:

Did the Depression hit pretty hard?

Havard:

Oh, it hit very hard. As a matter of fact, Butte actually never fully recovered from it. Well, I think that's an exaggeration. The war came on, and there was a demand for copper, and that re -invigorated Butte for a while. Then, after the war, the Butte underground operations became uneconomical, and the huge Berkeley Pit was developed. Eventually, Anaconda sold everything, and a Missoula contractor has bought all those properties and has made a great go out of it with open-pit mining.

Swent:

Was there open-pit mining as well as underground when you were there?

Havard:

Not when I was there.

Well, the summer ended, and I have many interesting little stories to tell about people I met. For instance, Big Jim Farley. You remember Big Jim Farley? Big Jim Farley was chairman of the Democratic Party, and he came to town, and our old dependable political reporter, for some reason, was not available, so I was sent out to this big home in Butte , which was owned by an Anaconda lawyer, to interview Big Jim Farley. Of course, the story that I was trying to get, and every reporter in the United States was trying to get, was who did he think was going to be the Democratic nominee for president? Every reporter was hunting for an angle. And I was not so naive that I didn't know that that was a story that would be nice to get.

Swent:

This was for the 1932 election?

Havard:

It was for the 1932 election, and this was in 1931. After the summer was over, I was kept on in the same role except I worked just weekends, Saturday and Sunday nights, reporting.

I went out for the interview, and Big Jim Farley who, of course, was a national figure, was just as nice to me--whom he could well recognize as a green, young reporter--just as nice as he could be.

Swent:

Good politician!

Havard:

So I finally popped out the question, "Well, Mr. Farley, who do you think is going to be the Democratic candidate?"

And he said, "It will be a Democrat from the state of New York."

That's all I could get out of him, and so that was my story the next morning in the paper. But that wasn't the end of my association with Big Jim Farley. Many years later when I was working for Kaiser Engineers, I was in the Waldorf Astoria lobby, and Big Jim lived in the Waldorf Astoria. I met him in the lobby and said hello to him, and I told him this story. And he said, "Well, I don't remember you, but I remember the stop and the house and talking to a reporter."

He was just delightful and wanted to know who I worked for, and I said, "Kaiser Engineers."

He said, "Well, I'm a great admirer and friend of Edgar Kaiser. Give him my best regards." So I did when I got back to Oakland. And apparently, soon after that, he died at a very ripe old age.

Swent:

I thought you were going to say that he remembered your name, because he was famous for remembering everybody's name.

Havard:

Yes, he was, but I was too small. He could remember the incident, but he couldn't remember me. That was fine.

Another very prominent person I interviewed was J. C. Penney, who stepped off the Olympian during a stop in Butte, and I was there to meet him. We talked on the platform, and of course the subject was the Depression. He opined that we were going to come out of it all right, and we would be okay. And he, again, as a very prominent businessman, was just as kind to me, as a green reporter, as he could possibly be, which I guess is characteristic of many big men.

Swent:

He started out not far from there, didn't he?

Havard:

He started in Wyoming, I think his first store was. Oh, I met a number of other celebrities along the way like that. So it was an interesting year. They liked me there; they liked what I produced. After the summer, they kept me as relief reporter on weekends for the school year- -one night in the police run and one night on the city run.

But right at the end of the school year, which was the end of my third year at Montana School of Mines, they said that they could no longer keep me, that the times were getting so tough that they couldn't keep me. So that meant no summer work. And there was no work; there was nothing. The mines were gradually shutting down. The Depression was clamping down hard on Butte. I tried everything you could think of to get a job.

I got two good, full years of stuff the three years that I spent at Montana Mines . Butte was no longer a source of employment. My uncle and aunt had some properties up in Rimini, all of these old log cabins with the false fronts , and they told me that we could live in one of them, my mother and I. We hired a truck, put our few possessions on the truck, went up from Butte to Helena to Rimini, and moved into this little old log cabin with a false front which had been a mine office at one time, many decades before. Then I just started hunting around for jobs anywhere, and trying to pick up a dollar here and a dollar there.

And then I got a job as a reporter for the Helena paper, covering the Montana State Fair, but of course that only lasted for a few weeks. But, one way or another, we had enough money to eat.

Then I had this amazing experience which I call Miracle Number One in my life, there having been a series of miracles in my life for which I am duly grateful. And this was the time when I had a job painting the inside of a cabin up in Rimini. Rimini was a kind of a resort, had turned into something of a resort town; there was no mining going on. The company I had worked for had finished their adit, and had been unsuccessful, and so there was nothing going on, but it still was a beautiful place to be.

A very distant relative of mine was having a cabin built for herself, a very nice cabin. I was hired to do some painting. I was, one day, up on a platform varnishing the ceiling, when she came in and said to me, "Jack, I understand you want to go back to college. "

I said, "I'd certainly like to."

She said, "I'm prepared to lend you whatever you need so that you can finish."

Well, I almost fell off the scaffold. Her name was Clara Holter Kennett, and she had lost two young men sons to illness. I found out later that she had a number of students she was putting through college on the same basis. She would talk around and find people that seemed to deserve some help, and she would help them, and as she was paid off by those who graduated, she re -lent the money without interest to others, so she had a continuing thing going. I guess it was sort of a living memorial to her own sons. She was a lovely, lovely woman.

So there I was suddenly with the means to finish, and where to go? I didn't want to go back to Montana Mines, because I wanted a broader education, and I particularly wanted to do more in the field of writing. And I wasn't changing my viewpoint that I wanted to be a mining engineer; I still wanted to do that. So I thought about several places, including Stanford and Harvard. I had some correspondence with Harvard, and the professor of mining engineering at Harvard was Donald McLaughlin. He wrote me back a very pleasant letter, as he would, you know, welcoming me if I could get there.

Well, I had in mind the debt that was going to face me when I got through, and so I cancelled all the places like Harvard and Stanford and decided to write to the University of Wisconsin, where my father had taught and where he died, and got a nice letter from the registrar welcoming me and pointing out that I could get a so-called legislative scholarship, which would relieve me of out- of -state tuition, which was a considerable amount of money, if my grades were up, and I mean up.

So I packed up and went to the University of Wisconsin and had a really wonderful three years there.

Swent:

Who were some of your teachers?

Havard:

Well, the outstanding group was the Department of Geology, which at that time had Leith, Mead, Twenhofel, and Winchell, who were really an outstanding "Great Four," you might say. All of them eminent in their fields. Then there were a couple of young men coming along behind them that were very bright. One of them was a man named Emmons , Con Emmons , who did great things with the petrographic microscope. There is no use going into the technology of that, but it was extremely interesting work. And the other one was Robert Schrock, who was my thesis advisor and later became chairman of the Department of Geology at MIT. So these were very, very bright men. And incidentally, Mead became chairman at MIT before Bob Schrock. They stole him away from Wisconsin. So they were a preeminent group.

Swent:

Was geology your major?

Havard:

It was a co -major. My elect ives were so balled up in the engineering curriculum, which is very strict as to what comes before what, that I had a lot of time to spend on geology, so I got a bachelor's and a master's in geology while I was getting my B.S. in mining engineering. The Engineering Department, of course, was first-rate, always has been, and still is, but the Mining Department was just average, but that was all right.

I took a very heavy load every semester, exceptionally heavy load, and I had to make almost all A's, and I did, so that I got my legislative scholarship every semester. That's a great incentive [chuckle]. The result was I graduated with high honors from both the College of Liberal Arts and the College of Engineering, spurred by finances [laughter] .

Swent:

But you were glad not to have to be working at the same time.

Havard:

That's right. I got a Ph.B. , Bachelor of Philosophy, and a Ph.M. , which was Master of Philosophy; that means "natural philosophy." It's an oldtime terminology; I doubt if they use that any more. Then, I got a B.S. in Mining Engineering.

Swent:

And an E.M.?

Havard:

Later on, I got an E.M. , after I graduated. At that time, the states were not licensing professional engineers to any great extent. So some of the universities were trying to set up some kind of program that would give a graduate engineer a professional status, so he could hang it on his wall. At Wisconsin, they had a professional engineering program for which you had to be out, I think, six years, and you had to have some kind of responsible position, and you had to write a thesis that was acceptable to the faculty. So I did all those things and got my E.M. , the thing I could hang on the wall as a professional engineer.

Swent:

What was the thesis that Schrock advised you for?

Havard:

Well, that was interesting. We have to go back to the English class. You know, I told you the story--! don't think it has been on tape about talking to my mining engineering professor who was my advisor when I first arrived there, and we worked out my program. I had to have a liberal arts subject, an elective. So we were looking through the catalogue, and I saw Advanced English Composition, under a woman named Helen C. White, which was for English majors.

And I said, "That's the thing I'd like to have, It says English majors, but do you think she would let me in?"

He said, "Well, I don't know, let's phone her."

So he phoned her, and she was delighted to have a strange animal like a mining engineering student come into her class [laughs]. I went into that class and enjoyed it tremendously, because she was a very bright and attractive woman, who wrote beautiful books. In fact, they were so beautifully written, they really didn't get much general sales. They were specialized books on Catholicism in the Middle Ages, and things like that. She was later president of the national AAUW [American Association of University Women] for two years, I think. At any rate, that was a wonderful course and a great privilege to learn at the feet of Helen C. White.

Swent:

What sort of things were you writing?

Havard:

She would hit us with various kinds of things, but if I had a chance, I wrote about mining. Some of the things got published in the university magazines. Anyway, I did all right. I was a straight-A student in that course, did better than the English majors did. But the first day, in walks a nice-looking blond co ed, and sits down next to me, which was the available chair, as I recall (she was just a little on the late side), and in the course of time we became friends .

She was really my first girlfriend, and she was absolutely delightful. She was a- -I get teary because I begin to think about things [pausing]. Sis--her nickname was Sis--sort of took me in, she sort of took me in hand in the university and saw that I got to the concerts and broadened my education.

Swent:

You hadn't had time for that sort of thing up till then, had you?

Havard:

She took a liking to me and just introduced me into the world of art and literature in the university. For example, she took me to hear Fritz Kreisler play the violin. Well, we became very good friends, and met a lot, and studied together. Incidentally, she was a Delta Gamma.

Swent:

What was her name?

Havard:

Her name was Florence Riddle, widely known as Sis. This diversion has a point to it, because her mother ran a summer camp up on Green Bay, a summer camp for small boys and girls. I was invited down to their home for Christmas one time, so they got to know me, and I was invited to be a counsellor up there, which meant that I had a summer job, which I badly needed.

Swent:

And a pleasant one.

Havard:

And a very pleasant one, which I knew nothing about. I went to Dr. Schrock, and I said, "I've got to do my fieldwork for the thesis somewhere this summer, and I've been invited to work as a counsellor up on Green Bay."

And he said, "That's just fine! There are some things that I want to look into, in those cliffs."

The cliffs along Green Bay are gorgeous, high cliffs of what was called the Niagara Dolomite. And so I had both my job for the summer, and I had my fieldwork for the thesis. I was very fortunate. Of course, Sis was a counsellor on the girls' side, and I was one of the counsellors on the boys' side of that camp. It was a wonderful experience.

Swent:

It sounds like a great summer.

Havard:

After camp closed, I climbed cliffs and gathered samples. Luck was with me again.

The following summer I repeated as counsellor at the camp, and I continued to gather samples from the cliffs, this time for my master's thesis.

Anyway, the three years went by, and in 1934 I got my bachelor's in geology. In 1935, I got my master's in geology and my bachelor's degree in mining engineering, and I had had a wonderful three years .

Swent:

The Depression was easing a little bit by then?

Havard:

It was easing a little bit, not much. Of course, I began to start looking for a job--I got out in 1935--and they were not easy to find in 1935. I thought, you know, I'd get some kind of a romantic job in the Andes or Australia, or someplace where mining engineers went and got romantic jobs.

I got one offer, from United States Gypsum Company. This came about because a Ph.D. in geology from U.S. Gypsum visited back at Wisconsin and talked to the geology professors and the mining professors about the quality of the graduates they had that he might be interested in. My name popped up, so I went to interviews in Chicago, and they hired me.

And of course, I was broke, as usual, or on the verge of being broke, because I had borrowed as little as I could borrow. My mother lived with me in Madison, incidentally. We always got a tiny little apartment somewhere. She couldn't leave me, you know. Anyway, I put her on the train to Montana and got into my little car and drove down to western Oklahoma.

Swent: