First-Hand:The Experimental Research Airplanes and the Sound Barrier - Chapter 1: Difference between revisions

| Line 203: | Line 203: | ||

[[File:2. Dragline.jpg|thumbnail|left|My father looking at one of the dragline shovels, circa 1951. Photo by the author ]] | [[File:2. Dragline.jpg|thumbnail|left|My father looking at one of the dragline shovels, circa 1951. Photo by the author ]] | ||

[[File:3. Crawler-Transporter.jpg|thumbnail|right|During a 1976 visit to the Kennedy Space Center, we walked over to get a closer view of one of the Apollo Moon Rocket crawler transporters that carried the rocket from the vertical assembly building to the launch pad. As we got closer I was astounded to again see the Marion Power Shovel logo on the crawler tracks. It turned out this huge machine had been built by the same company that built the Colstrip mine power shovels some four decades before and the tracks looked almost identical to the dragline tracks. A dramatic demonstration of the sophistication of mechanical engineering even in the 1930s. NASA photo ]] | |||

A Marion scoop shovel removing overburden, circa 1951. The size of the shovel can be appreciated from the size of the rail cars alongside. Photo by the author | A Marion scoop shovel removing overburden, circa 1951. The size of the shovel can be appreciated from the size of the rail cars alongside. Photo by the author | ||

Revision as of 20:47, 24 July 2016

By David L. Boslaugh, CAPT USN, Retired

Table of Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. Life in a Montana Coal Mining Town

- Moving to Colstrip

- The Coal Mine

- Camp

- School

- World War II

- Last Stand at Rosebud Creek

- Chapter 2. Little Falls, Minnesota

- We Move

- Little Falls High School

- Home Made Equipment

- Little Falls’ Close Brushes With Fame

- The Westinghouse Science Talent Search

- The Holloway Plan

- Chapter 3. The University of Minnesota

- The Aeronautical Engineering Curriculum - 1950 - 1955

- The Rosemount Aeronautical Research Laboratory

- Chapter 4. USS Henry W. Tucker (DDR 875)

- Chapter 5. The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics

- Origin of NACA

- The Langley Laboratory

- The Ames Laboratory

- Chapter 6. Inception of the Experimental Research Airplane Program

- Compressibility

- Unanswered Questions

- Chapter 7. The X-1 Project

- Design

- The XLR11 Rocket Engine

- First Glide Flights at Pinecastle

- Move to Muroc

- Powered Flight

- Going Supersonic

- Chapter 8. The D-558-I Skystreak Project

- Design

- Skystreak Number 1

- Skystreak Number 2

- Skystreak Number 3

- Chapter 9. Beyond Mach 1

- To Mach 1.45 in X-1-1

- New Names

- The Ill Fated X-1-3

- Chapter 10. The D-558-II Skyrocket Project

- Design

- Ground Launch

- Air Launch

- Chapter 11. The Second Generation X-1s

- Inception of the Second Generation

- Design

- The X-1C

- The Fate of the X-1D

- The X-1A

- Dynamic Stability and Control Investigations

- Roll Coupling

- Chuck Yeager’s Wild Ride

- The End of the X-1A

- The X-1B

- The X-1E

- Design

- First Flights

- Joe Walker’s Belly Slide

- One of the Few Survivors

- Chapter 12. The X-2

- Inception of the X-2 Project

- Design

- The XLR-25 Rocket Engine

- Flight at Last and then Disaster

- Starting the Research Program

- Toward Mach 3

- Chapter 13. At the High Speed Flight Station

- Loss of Captain Apt and the X-2

- The Computers

- Pitch-up and the F-104 Fighter

- Marian the Librarian and Copilot

- The F-107 Project

- A Dutch Roll Can Kill You Chapter

- Chapter 14. Research Airplanes Without Rockets

- The Douglas X-3, A Hoped-for Mach 2 Turbojet

- Inception

- Design and Construction

- Flight Testing

- The Douglas X-3, A Hoped-for Mach 2 Turbojet

- The Northrop X-4 Semi-tailess Research Airplane

- Inception

- Design and Construction

- Flight Testing

- The Bell X-5 Variable Sweep Research Airplane

- Descent from the Messerschmitt Me P.1101 Prototype Fighter

- From Messerschmitt to Research Airplane

- Design and Construction

- Flight Testing

- The Convair XF-92A Delta Wing

- Inception

- Design and Construction

- Results

- The Other X-Planes

- Chapter 15. The X-15 Project - Design, Construction, and Preparation

- Inception

- Scotty Crossfield Leaves NACA

- Design and Construction

- The Airframe

- The Auxuliary Power Units

- The XLR99 Rocket Engine

- Control System Design

- Flight Test Instrumentation

- The Inertial Platform Reference System

- Engine Trouble

- Rollout and Delivery

- The David Clark Co. MC-2 Full Pressure Suit

- The High Range

- Simulator and Centrifuge Testing

- Chapter 16. The X-15 Project - Flight Testing

- Research Goals

- Preparing for a Test Flight

- The Mother Planes and Chase Planes

- First Captive Flights

- First Glide Flight

- The Sidearm Controller

- Scotty Crossfield’s Wild Ride

- Farewell to the High Speed Flight Station

- First Powered Flight

- Bent, But Not Broken

- The XLR99 Engine Arrives

- Goodbye to the Lower Ventral Fin

- Number Three Comes Back

- Roll-Over at Mud Lake

- X-15A-2: the Phoenix

- Loss of Major Adams and X-15-3 .

- Program Termination

- End Results

- References

Preface

It is probably because of my unusual naval career that IEEE historian John Vardalas asked me to do a history for the Engineering and Technology Wiki web site. On reflection, the career was at least a little different than a normal naval career. Starting with only a year and a half of destroyer duty then followed by three years in aeronautical research working with experimental research airplanes in the Mojave Desert, then five years in the first Navy project to put digital computers in shipboard weapon systems, three years in a naval shipyard learning the practical aspects of the business, then four years involved in the engineering aspects of cryptography and cryptology. This was followed by naval communications research and development work and projects continuing to introduce standardized digital computers to naval weapon systems. I had already written about the digital computer experience in my book “When Computers Went to Sea” and also in the Engineering and Technology History Wiki article titled “No Damned Computer is Going to Tell Me What to Do,” so I proposed writing about my early times, education, and the three years Marian and I spent at the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics High Speed Flight Station. Here we were privileged to work with the Nation’s collection of rocket powered experimental research airplanes ranging from sister ships of the Bell X-1 to the North American X-15. We were also privileged to work with some of the finest test pilots in the world and with Station engineers who taught me a lot.

Even though you might be involved in a program for a number of years, there is still a lot of research needed to put the whole story together. For example, even though I was in the Naval Tactical Data System project for five years, I spent six years researching the project and gathering material before starting “When Computers.” Writing “The Experimental Research Airplanes and the Sound Barrier” was no different; much research was needed. I am particularly indebted to the experimental test pilots who chronicled their experiences. This includes:

- Chuck Yeager’s book: “Yeager”

- William Bridgeman’s book: “The Lonely Sky”

- Scotty Crossfield’s book: “Always Another Dawn,” and

- Milton O. Thompson’s book: “At the Edge of Space - The X-15 Flight Program”

Other very useful references were:

- James R. Hansen’s biography of Neil Armstrong: “First Man - The Life of Neil A. Armstrong”

- Michelle Evan’s book: “The X-15 Rocket Plane - Flying the First Wings into Space”

- Michael H. Gorn’s book: “Expanding the Envelope - Flight Research at NACA and NASA”

- Dennis R. Jenkins’ book: “HYPERSONIC - The Story of the North American X-15”

- Jay Miller’s book: “The X-Planes - X-1 to X-31,” and

- Arthur Pearcy’s book: “Flying the Frontiers - NACA and NASA Experimental Aircraft”

Probably the the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics’ and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s most valuable product is the huge quantity of technical reports they have issued over the years. Now most of the older reports that were once classified have been declassified and can be downloaded via the internet. These have been a most valuable source of reference material, for which this writer is most thankful. Also copies of the High Speed Flight Station (later named the Flight Research Center) X-PRESS newsletters over the years have provided much useful information. Our thanks to the Center for keeping your former workers on your mailing list.

There are certainly omissions and errors in the following narrative, and they are mine. Fortunately, publishing on the web allows correction of errors and omissions in minutes, not to mention addition of new findings. If the reader sees such errors or omissions they are encouraged to E-mail me at dboslaugh@verizon.net. I look forward to hearing from you.

Introduction

Airplanes fascinated me since early childhood, and I built and flew model airplanes starting at the age of six. This finally progressed to making my own airplane designs; some of which didn’t fly too well. As a teen-ager I knew that I wanted to be an aeronautical engineer, and under a navy scholarship I studied aeronautical engineering at the University of Minnesota, with a goal of being a naval aviator, and eventually an engineering test pilot. However, my hoped for naval aviation career was cut short by less than 20-20 eyesight that came out in the navy flight physical exam. Instead, duty upon graduation was to be assistant engineering officer on a destroyer based in Long Beach, California, where as great compensation I found my future wife Marian.

After a year and half on the destroyer, a most happy surprise arrived in the form of a letter from the Bureau of Naval Personnel offering a chance to volunteer for duty as an aeronautical research engineer with the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (now NASA). This resulted in a three-year assignment at the High Speed Flight Station in the Mojave Desert, where ten years before, Capt. Chuck Yeager had made the first faster than sound flight in the Bell X-1 research airplane. Sister ships of the X-1 were still there, as well as a host of other experimental research airplanes. This was beyond my wildest dreams, I was going to get to work with research airplanes I had only ever read about.

Marian and I moved into quarters at Edwards Air Force Base (the Air Force Flight Test Center, and host of the High Speed Flight Station), and Marian soon had a job in the Station’s technical library. In the space of a couple of years she was in charge of the library, and one of the duties of the librarian and her staff was attending quarterly library conferences at the other NASA research centers. Usually the most economical way to transport the librarians to their conferences was the Station’s DC-3 utility airplane, and the junior test pilot got the job of transporting the librarians. Our junior test pilot was a young fellow named Neil Armstrong who, at the beginning of each flight, would ask for a volunteer copilot. Marian would always volunteer, and now with a straight face, she can say she flew copilot with Neil Armstrong.

Marian and I got to work with experimental research airplanes spanning many of the numbers from X-1 to X-15. We both watched the first unpowered drop flight of the X-15 from the station roof, where we saw test pilot Scotty Crossfield end the flight in a wild pitching oscillation that was not a disaster only because he managed to hit the dry lake bed in a nose up pitch; that ruined the landing gear.

Our next duty station was the Naval Postgraduate School at Monterey, California, where I had hoped to get a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering. But the Navy, having a growing need for electronics engineers educated in the emerging technology of digital computers, changed my specialty to computer systems engineering for the rest of my 30-year naval career.

Chapter 1. Life in a Montana Coal Mining Town

Moving to Colstrip

One of the earliest things I can remember is watching my dad sharpen chisels in his wood working shop in the basement of our home in Colstrip, Montana. It was fun to put my hand into the stream of sparks flying from the chisels and feel their sharp little stings. When he finished with the chisels there was a small gray pile of metal filings on the floor, and Dad brushed the filings on to a sheet of paper. Then he held a horseshoe magnet under the paper, tapped the sheet, and said, “Look at this David.” Magically the filings began to move and formed sets of curved lines connecting the poles of the magnet. When you moved the magnet, the lines would move. He said, the lines showed the lines of force of the magnet; which really didn’t mean a lot to me. I played with the magnet and the paper for a long time and wondered, “What are these strange forces that can let you move things around without really touching them?” Later, when Brother Richard and I were maybe seven or eight years old, Dad taught us how to wind electromagnets, and then how to build a rudimentary telegraph system, and then how to make small battery powered electric motors out of nails, wire and bits of wood.

When he was growing up, Dad had wanted to be an electrical engineer, but fate had other plans for him. He and his three sisters had been born and raised on a farm near Vilas, South Dakota, and dad had told us how our grandfather not only devised improvements to his farm equipment, but had actually designed some of his own farm machinery. He told us how one very rainy year Grandpa had actually replaced the wheels on some of his equipment with barrels to keep the wheels from sinking into the soft earth. He was able to keep on farming that wet summer when other farmers couldn’t. When dad and his sisters started nearing junior high school age, Grandma and Grandpa B. decided to move to Oscaloosa, Iowa, so that their children could get a better education than they could get in rural South Dakota. Grandpa’s plan was to open a school of business in Oscaloosa which would bring another of his talents into play; fantastically good penmanship.

In the early 1920s, running a small business involved using a number of paper forms that called for highly legible penmanship, and Grandpa B’s classes were going to teach the use of the forms as well as penmanship. He also envisioned printing the various forms to sell to businesses. Grandma B. once showed me the printing plates for Grandpa’s penmanship book. He had done all the penmanship illustrations for the plates, and they were truly elegant. Somehow this particular talent skipped a generation when it came to me. In Colstrip Grade School the teachers handed out “bluebird cards” to inspire the young students to good penmanship, but in all my years in grade school, I never got one bluebird card. It got so bad our teacher would send me out of the room on an errand when she handed out the bluebird cards. It is good we have word processors now.

The Boslaugh family moved to Oscaloosa early in 1923, and it was Grandpa’s plan to open his school that fall. In the meantime, he would be preparing his class material, and he also got a job working on the local Minneapolis and St. Louis Railroad doing track maintenance. Tragically, on 5 May 1923 he was killed in a railway accident when the crane boom on the car he was riding was misaligned and caught on a bridge timber. Dad’s hope of studying electrical engineering were dashed. Instead, Grandma B. found work in the dormitory kitchen of nearby John Fletcher College in Oscaloosa where she managed to get all four of her children through college. The college had two specialties, theology and education, and Dad was told he was either going to be a preacher or a teacher. Dad chose teaching, and decided to specialize in journalism and the teaching of manual arts.

Upon graduation, Dad’s first teaching job was as principal of a small high school in Flaxville, Montana, up in the far north eastern plains of the state. He also taught journalism and manual arts. In the summers he would find work building housing at nearby Fort Peck Dam on the Missouri River. Here he sharpened his blueprint reading and carpentry skills, as well as pouring and finishing hundreds of tons of concrete. In 1936 Dad was offered the position of Superintendent of Schools in the coal mining town of Colstrip in southeast, Montana. He would also be principal of the high school, and again would teach journalism and manual arts. The dark cloud that pushed Dad into teaching instead of electrical engineering may have also had a silver lining. Even at the bottom of the great depression, teachers could usually find employment because the last thing a municipality would want to do would be to shut down their schools, whereas newly graduated electrical engineers were standing in bread lines.

The Coal Mine

Whenever Brother Richard and I needed more wire for our electrical constructions and experiments, Dad would say, “Let’s go out to the mine and get some more blasting wire.” There was always an ample supply of used fiber-insulated copper blasting wire lying on the surface of the exposed coal seam, and the miners were glad to see us roll it up and take it away. They always used new wire for the next blast for safety reasons. Then we would stop at the company office and dormitory heating plant to get a supply of blasting powder boxes. The heating plant burned the boxes and there would always be a supply of intact boxes with the colorful “Atlas Blasting Powder” logo emblazoned on the box. These boxes were very well made of half-inch wood about sixteen inches long and a square foot in cross section, and provided all the wood we needed for our projects, as well as making substantial storage containers. Everybody in Colstrip stored their belongings in powder boxes.

Colstrip was a company town owned by the Northern Pacific Railroad (NP), and the mine supplied most of the coal used by the NP locomotives. We were told it was the largest strip mine in the world. Originally the NP owned and operated underground coal mines at red Lodge and Chestnut, Montana, to supply their locomotives. However, a little before 1920 the miners there unionized, causing increasing strife and management problems for the Railroad. In 1923 the NP resorted to developing a new surface coal stripping mine in Rosebud County, Montana, about 35 miles south of the town of Forsyth. The strip miners were much more mechanized than the manual laboring underground miners, and not interested in unionization. The Railroad named the company town established near the mine “Colstrip,” and only NP employees could live there. They called the coal “Rosebud” coal, and found it cost only one fourth as much to deliver a ton of coal to a locomotive as the cost for the underground coal. There was one drawback, however, the sub-bituminous Rosebud coal had about half the heating value of the harder underground coal. The economics were still in favor of Rosebud coal, but to get the needed engine power the NP had to resort to building a new breed of locomotives having fireboxes about twice the size of conventional locomotives. [16, pp.78-80]

Their first new locomotives, built at the American Locomotive Works Schenectady Plant, featured a new wheel arrangement for locomotives. Previously, the largest of steam locomotives used only two idler wheels under the firebox, however the new Northern Pacific Class A machines needed four wheels to support the large fireboxes, resulting in a new 4-8-4 wheel arrangement. The NP’s quest for larger fireboxes to efficiently consume the Rosebud coal, and increased power in general, was finally consummated in the Northern Pacific Class Z-5 “supersteam” engine having a 2-8-8-4 wheel arrangement. It had two sets of eight-each drivers, each set powered by its own cylinders. The firebox on these monsters was 22 feet long, nine feet wide, and seven feet high. The Northern Pacific advertised these machines as the wold’s largest and most powerful locomotives, as well as being the technological peak of the American steam locomotive. [16, p. 80, pp. 94-96]

The coal seam mined at Colstrip was called the Fort Union Formation. It was under about 100 feet of soil overburden and was 24 feet thick. Two types of huge power shovels were used in the mine, both built by the Marion Steam Shovel Company, however both were actually powered by electricity from huge trailing high voltage cables. The first type was called a dragline, and it was used to remove overburden soil by dragging a large bucket horizontally across the ground. The bucket would be emptied onto a growing spoilbank alongside the huge 200-foot wide groove the shovel was digging in the earth. The groove would be excavated down to the level of the coal seam and then the dragline would be moved on to uncover more of the groove until about a mile of coal seam had been revealed. Then, after blasting with dynamite to loosen the coal seam, a huge scoop shovel would be driven in to scoop up about a 100-foot wide strip of the seam and load it into railroad coal cars rolling on rails laid on the remaining 100-foot wide strip of coal seam. When the scoop shovel was not being used to load the cars, it could also be used in removing the earth overburden. [63]

When the dragline had uncovered a mile or so of coal seam, it would be driven back to the starting end of the now half-removed seam to remove a new strip of overburden alongside the remaining side of the seam. The removed overburden soil would then be dumped into the empty strip where the coal had been removed to build a new spoilbank alongside the original spoilbank. The strip mine would then continue moving sidewise across the landscape leaving miles of spoilbanks in its wake. The spoilbanks were aptly called because any topsoil would have been dumped at the bottom of the bank, and no vegetation would grow on them for years. No attempt was made at smoothing them or any other form of reclamation. The only advantage I can recall of the spoilbanks was were they were fun to play in, and because the soil was well broken up, the rich supply of fossils they held was easy to retrieve. We would bring home all kinds of fossilized bones, turtle shells, sea shells, smooth rock rods that had probably once been the cartilage skeletons of ancient sharks, and myriad leaf and flower shapes preserved in the layers of rock.

A Marion scoop shovel removing overburden, circa 1951. The size of the shovel can be appreciated from the size of the rail cars alongside. Photo by the author

An example of the spoilbanks left from the Colstrip mine. Photo by the author

The mine was still in operation in 1951 when Dad and I visited Colstrip, but production had been considerably cut back because there were only a few steam locomotives left on the Northern Pacific lines. Mining then ceased in 1958 when all Northern Pacific steam locomotives had been replaced by diesel units. The end seemed to be in sight for Colstrip, however, the town and the mines would eventually experience a new life. More about that later.

Camp

To the residents of Colstrip their village was not called a town, to them it was “camp.” If someone said they were going to town, they meant they were going to Forsyth a larger town on the Yellowstone River some 35 miles north of Colstrip. Forsyth had a much wider variety of shopping than the one company general store in Colstrip; you could get your car repaired at a garage, and there was even a movie theater. A truck with mail for the post office in the general store as well as supplies for the store came from Forsyth once a day; only it was not called the mail truck, it was the “stage.”

Even though we were living in the middle of the great depression we in Colstrip did not seem to be touched by it, other than seeing many unemployed men riding the railroad cars that passed through Forsyth. It seems that if the family breadwinner had a job at that time, you were OK. It was the families without work that fell out of the bottom and had no safety net. Even though the ranches and farms around Colstrip had no electricity (other than a wind charger) or indoor plumbing, we had both because of the power line running down to the mine for the big power shovels. Because of the ample supply of coal, all heating was done with coal, and every company house had a coal bin next to the furnace room that the company kept well supplied. Wood kindling to start fires came from the ever present powder boxes. The coal bin also was a source of wondrous entertainment, where Brother Richard and I would spend hours splitting lumps of the soft coal to see the fantastic imprints of prehistoric leaves and flowers.

Our communication with the outside world also seemed to be totally modern and up to date. Even though the individual company houses did not have telephones, the company office had a couple that could be used in emergencies. Also, if you needed to correspond with less delay than offered by the US postal system, you went down to the Western Union telegraph office at the railroad station. Colstrip had a spur line running down from Forsyth for the coal trains, and if you needed to get into Forsyth by rail, to catch a mainline train for example, you could buy a passenger seat in a coal train caboose. We could reliably tune in one radio station: KGHL in Billings, Montana, about 100 miles away. From KGHL, we got up-to-the-minute daily news, Jack Armstrong, The All American Boy - right after school every day, the spooky Inner Sanctum program, Red Slelton, Fibber Magee and Molly, the Jack Benny Show, the Lone Ranger, and on Saturday mornings the Orson Welles broadcasts. We knew right from the start that his “War of the Worlds” was just a radio program, but it was satisfyingly scary just the same. One really great thing about listening to radio shows, as compared to television, was you could work on model airplanes, or other things, without having to look up at a screen. News magazines such as Time, Life, Colliers, and the Saturday Evening Post were also an important connection with the outside world, not to mention the Sunday Denver Post newspaper. The Sunday paper actually came in the mail on Wednesdays and was one of the two high points of the week for me. Even though they were forbidden fruit, and an object of derision by our teachers, the paper had the comic strips including “Prince Valiant”, and my favorite “Tim Tyler’s Luck” about the adventures of a Coast Guard sailor. Sometimes that strip had model ship layouts that you could paste to cardboard, cut out, and assemble.

The land outside Colstrip also offered endless entertainment possibilities. First was the “swimming hole” a flooded strip mine about a half mile walk from camp. The company had equipped it with changing houses, a diving board, and a raft. During the summer they also provided a life guard, usually one of the high school students who had taken the Red Cross life saving course. They also gave swimming lessons, and just about every kid in and around landlocked Colstrip knew how to swim. The swimming hole, was actually about a half mile long and was stocked with rainbow trout for fishing. The local sand rock outcroppings were another attraction. These large soft sandstone monoliths had been sculpted by the wind and rain for thousands of years and offered caves, tunnels, and other formations that offered more possibilities to a young imagination than Disneyland ever would. Some of the sand rock formations had flint outcroppings that had been known to the indians for many years. Here they had chipped arrowheads from the flint for millennia. Dad would often take us out to “Eagle Rock” to turn the earth over in a search for arrowheads, and there is hanging in this room a display of a number that we found. There is one thing notable about them. None is complete; every one has some sort of flaw. That is the only reason we could find them, because in each case something had gone wrong in the chipping process and the maker it had thrown it away. Probably each one up on the wall has some kind of indian expletive or swear word connected with it.

School

Dad’s school system consisted of two two-story wood frame buildings in opposing corners of a school yard about two acres in extent. One was the grade school and the other the high school. The lower story of the grade school was the manual training wood shop and storage, and the upper story had three classrooms. Two of the classrooms held children in three grades and the third had two grades together. One teacher in each room would attend to one class level at a time while the other classes studied. Often a student in one of the studying classes would raise their hand to answer a question Miss Flannigan had addressed to a different class level, and she would have to remind the eager student he or she was in the wrong class, and to get back to studying.

Each classroom had a large black stove for heating, and naturally burned coal. One of our favorite activities was to throw a hand full of 22 caliber rifle shells in the stove and then listen to the popping and banging of the shells detonating. This really got Miss Flannigan’s attention the first couple of times because she didn’t realize what was going on. Later, though, she would not even raise her head, but would just quietly say, “I wish you boys would stop wasting your 22 shells in the stove.” Once one of our teachers caught me drawing a sketch of a Buck Rogers type rocket, which prompted her to give me a short lecture that she knew from good authority that men would never leave the bounds of earth because, “The vibration will shake them to pieces.” Another time this same teacher queried each student in turn as to what they had for breakfast that morning. Most answers were along the lines of eggs, bacon, and pancakes with butter; which was very satisfying to her because they were getting good nutrition, furthermore her father owned a dairy farm. My answer of, “a bowl of Cheerios,” appalled her, and the reason given that the Cheerios box came with a model of a Japanese Zero fighter was far from satisfying. She said she was going to talk to my father about my poor breakfast diet.

I have mentioned that one of the high points of my week was when the Denver Post comic strips came on Wednesday. The other was Friday when school classes were over because brother Richard and I were often invited to ride the school bus to one of my friend’s ranch homes to spend the weekend. One ranch student, Wallace McRea, was two years behind me in Colstrip grade school, and I remember him mainly as a very quiet contemplative young fellow. Later, in addition to running his 30,000 acre family ranch, he wrote a number of books of prose and poetry and became regarded as the Montana cowboy’s poet laureate. In one of his books he described our school bus.

We ranch raised children rode to school in what was euphemistically called a school bus. In reality, it was a black half-ton Chevy delivery van equipped with a pair of pastel pink and white cotton-blanket covered two-by twelve-inch plank benches that were bolted to each side of the interior of the back of the panel truck. The two rear doors did not close together tightly. In fact there was such a gap between them that you could watch the road fly by on rainy days. When it was dry, which was usually the case, you couldn’t see any thing because of the clouds of scoria dust that billowed in through that space in the doors. [37, p.44]

Wally went on to describe one of their favorite bus drivers, Helen:

Our parents did not approve of Helen, but despite being thrown around in the back of the delivery panel and gathering even a thicker layer of dust than usual, we liked her driving. She brought excitement into our lives. We found the threat of death or maiming somehow thrilling. And the fact that we had a daredevil driver that would pass the other busses satisfied our competitive spirit. [37, p.52]

Riding in the bumping, rolling, shaking bus that always seemed to be exceeding the speed limit, if there was one, was very exciting. But what was really exciting was life on the ranches around Colstrip. None of them had electricity other than a wind charger that fed a couple of car batteries and lit a couple of light bulbs in addition to powering a radio. Kerosene lanterns were the main source of lighting, which I thought was really great, and some of the more up-to-date places had a water hand pump right beside the kitchen sink. Others had a hand operated water pump out in the yard, and each had an outhouse with a Sears and Roebuck or Montgomery Ward catalog hanging on the wall to provide paper. It was always very satisfying to get scared while listening to the “Inner Sanctum” radio program in the dark. Other than the radio, most of the ranches also had a wind-up RCA Victrola record player. During World War II it was impossible to find metal needles for the Victrola, but you could buy needles made of sharpened bamboo sticks. They were good for one play each.

The village of Lame Deer was the headquarters of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation about 25 miles south of Colstrip. The reservation had its own schools, but some indian families elected to send their children up to Dad’s schools instead. They would be driven up on Monday morning and would stay the week with Colstrip families, sometimes in trailers in their backyards. One of my greatest treats was to be invited to go home with classmates Turkey Shoulder Blade or Susan Running Deer on Friday to spend the weekend on the reservation. The Little Bighorn Battlefield, site of Lt. Col. George A. Custer’s last stand, was about 35 miles west of Lame Deer, and to Brother Richard and I, it was a nice place to have a picnic and look for cartridges and arrowheads. That is until the movie “They Died With Their Boots On,” featuring Eroll Flynn in a very euphemistic portrayal of Custer, came out. Then we realized the battlefield had some historic significance rather than just being a picnic ground. The Northern Cheyennes had a much different view of Custer, and we even met a great grandfather who not only told us he had been in the battle, but had also fired the shot that killed “Squaw Killer” Custer. We firmly believed him, and there was no one around who could contradict.

World War II

I was sitting out on the front steps on a Sunday afternoon sanding a model plane part when Dad came out and said the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor. Inside Mom was frantic because she was sure we were all going to be slaves of the Japanese. I had no idea where Pearl Harbor was and Dad told me it was in the Island of Hawaii. There was a big wall map of the world in the school building across the street and I walked over to locate Pearl Harbor. It seemed to be a comfortable distance from Colstrip, and Japan was even further away. There did not seem to be any worry about bombs falling here, however in a few months there were armed civilian guards around the coal mine because of its strategic importance. We already had a large vegetable garden in our back yard plus an even larger corn and potato plot on the nearby Vern Wymer ranch. Furthermore Dad was an avid fisher and hunter and supplied a lot of our meat that way, plus he would occasionally buy a “side of beef” from a rancher and have it packaged to store in a rented freezer locker. There was food rationing, but I don’t think the people in Colstrip or the nearby ranches ever used all their ration coupons. Our mother also did a lot of canning and got an extra sugar allocation for that. There was definitely a metal and rubber shortage, and I remember when wooden soled shoes came out. There were constant metal and rubber scrap drives, and we had great fun accompanying our elders out to the countryside to help recycle every abandoned car and bit of rusting farm machinery for the war effort. Mom also saved all her cooking grease and fats to be turned back into munitions. Then there were the War Savings Stamps. We were encouraged to spend all our dimes on savings stamps that would be pasted into a little book. When the book contained $18.75 worth of stamps it could be converted to a War Savings Bond that would be redeemed for $25.00 when mature in ten years.

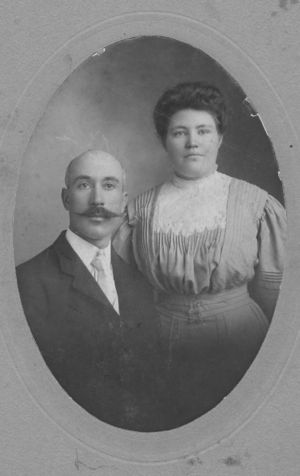

Our mother Opal Fern Burkes at age 16. Her grandparents lived in Oscaloosa, Iowa, and owned and managed three farms on the outskirts, one of which they gave to our grandfather, Elmo Burkes. Belonging to the Book of the Month Club, Mom was an avid reader, and also a very imaginative story teller. You never knew when she left the bounds of reality and entered the world of fiction. She also gave piano and guitar lessons. Photo from the author’s collection

With the advent of war, Dad converted his wood shop classes from making small furniture items to making airplane recognition models. The government provided standard plans for the models and his students shaped them out of solid pine wood. Then they painted the models black and shipped them off to the Army and Navy. To me, they were works of art, and I imagine every high school shop class in the nation was making a like contribution to the war effort. In 1944 Dad was 35 years old, and in March of that year a letter from his draft board gave him 60-day notice that he would be called to report for a physical exam. Instead of being drafted, he elected to volunteer for naval officer candidate school. Upon graduation he was commissioned a lieutenant (junior grade) rather than the lower rank of ensign because of his master’s degree in journalism. With his service entry, our mother, Richard, and I had to move from the company town of Colstrip to nearby Forsyth, Montana. Our parent’s divorce decree was finalized soon after.

Upon graduation from OCS, Dad listed the Naval Civil Engineering Corps (CEC) as his duty preference. The first naval construction battalions, under the command of CEC officers, had been established in early 1942 and Dad had always admired the “Fighting Seabees.” He wanted to be one of them, and requested an interview with a young CEC officer. The first question put to him was, “In what field is your engineering degree?” Dad replied he had degrees in education and journalism, upon which his interviewer replied that even in wartime he needed an engineering degree to get into the CEC. Dad’s rejoinder that he bet he had built more buildings and poured more concrete than his interviewer, did not hold much water. He ended up specializing in harbor operations and harbor command.

My father Donald R. Boslaugh upon graduation from Officer’s Candidate School in 1944. Photo from the author’s collection

Dad and Uncle Lewellin on Okinawa in 1945. Uncle Lew was married to Dad’s sister Beatrice, and was in the Army Chaplain Corps. Photo from the author’s collection

By 1945, Dad was on the island of Okinawa in training for the invasion of Japan. His job would be to go in with the third wave of an amphibious invasion and begin restoring harbor facilities. Many years later, I learned in my Naval Science Amphibious Assault class that the third wave of an invasion normally got the worst resistance because the opponents had usually recovered from the initial bombardment by that time. There has always been controversy regarding whether the dropping of A-bombs on Japan were the definitive causes of the Japanese surrender, but in any event I credit the A-bomb with allowing him to live to the ripe old age of 95. With war’s end, Dad was posted to the harbor command in Pusan, Korea. The Koreans wanted the Japanese out of Korea immediately so his first task was to go inland with a few enlisted men and an interpreter to disestablish a school for Kamikaze pilots. Between he and his men he had a 45 caliber automatic pistol and they each has a sub machine gun. The couple of hundred young Kamikaze candidates could have easily overwhelmed them, but they turned out to be amazingly docile and obedient while they loaded them into commandeered gondola railroad cars. Maybe they were glad to be going home.

Last Stand at Rosebud Creek

In 1983 while I was browsing through the Smithsonian Institution book store, a title leapt out at me, “Last Stand at Rosebud Creek.” I had once lived near a Rosebud Creek so I pulled the book out. Good Lord! It was about the little town of Colstrip where I had once lived. It was about the conflict between Montana Power Company and the ranchers who owned land around Colstrip. The book contained many names of persons I remembered including Wally McRae, one of the opposition leaders. In 1958, the Northern pacific had ceased mining Rosebud coal and the Montana Power Company negotiated a lease purchase agreement with NP to take possession of the town of Colstrip, the mining equipment and a coal field having about 60 million tons of coal. Montana power did not mine any coal there in the ensuing ten years and many of the homes were rented by local farmers and ranchers who preferred a community life. [51, p.5-6, 37]

In 1968 Montana Power (MP) started mining again on a small scale to provide coal for its power plant in Billings, Montana, as well as other power plants. However, in 1972 MP elected to build the first of four “mine mouth” power generating units to directly consume Rosebud coal, and local ranchers were well aware that as Homestead Act owners they did not own underground mineral rights to their property, so the coal interests could possibly do irreparable damage to their environment. By 1986 there were four such plants in Colstrip capable of producing 2,100 million watts. The story tells how McRae and his compatriots were at least able to require the coal interests to get environmental pollution permits and carry out land reclamation of the spoil banks. [51, p.73-74, 76-79, 92]

Western Energy Company, the present mine and plant owner, removes and stores the top two feet of top soil. Then, after mining, the spoil surface is regraded resembling its original contour, the topsoil is replaced, and native grasses, forbes, bushes, and trees are planted. Permanent revegetation is complete in about three years. In some cases, instead of this type of planting, local farmers lease the reclaimed land to plant grain fields and alfalfa. The company brochure goes on to state:

- "The mine is required to keep reclamation contemporaneous with mining. WECo disturbs approximately 250-350 acres annually for mining purposes, and the company also reclaims and revegitates 250-350 acres annually. An average of 20,000 trees and shrubs are planted each year.

- Over $2 million was spent initially on reclamation research in order to meet regulatory requirements.

- WECo has reclaimed and revegitated about 7,400 acres to date (2007)". [63, p.3-4]

This is the countryside just outside of Colstrip in 1951 showing what the land looked like before mining. The start of a spoilbank can be seen at center far left. Even though the spoilbanks are now graded and replanted, many features such as our wondrous sand rock formations are gone forever. Photo by the author

References

Note: The list below applies to this and all following chapters.

[1] Alex. Dan, Bell X-5 Jet-Powered Technology Demonstrator Fighter Aircraft, Military Factory.com, 3 November 2013 http://www.militaryfactory.com/aircraft/detail.asp?aircraft_id=644

[2] Anderton, David A., Sixty Years of Aeronautical Research - 1917-1977, National Aeronautics and Space Administration - U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.,1980, Stock No. 033-000-00736-1

[3] Aviation Safety Network, Flight Safety Foundation, Aircraft Accident Boeing 707, http://aviation-safety.net/database/record.php?id=19591019-0, www.flightsafety.org

[4] Bridgeman, William, and Hazard, Jacqueline, The Lonely Sky, Bantam Books, New York, 1955, ISBN 0-553-23950-3

[5] Bureau of Naval Personnel, Letter to ENS David L. Boslaugh, 5 June 1956

[6] Christy, Joe and Ethell, Jeff, P-38 Lightning at War, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 2001, ISBN 13: 978-0711007727

[7] Crossfield, A. Scott, and Blair, Clay, Jr., Always Another Dawn - the Story of a Rocket Test Pilot, The World Publishing Company, Cleveland and New York, 1960, Library of Congress Cat. Card #: 60-14641

[8] Day, Richard E., Coupling Dynamics in Aircraft: A Historical Perspective, Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards, California, NASA Special Publication 532, 1997

[9] Davenport, Christian, “Lockheed Martin joins race to build hypersonic aircraft,” The Washington Post, 26 March 2016

[10] David, Shayler, and Moule, Ian A., Women in Space - Following Valentina, Praxis Publishing, Chichester, UK, 2005, ISBN 1-85233-744-3

[11] Dildy, Doug, Thompson, Warren, F-86 Sabre vs MiG-15: Korea 1950-53, Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY2013, ISBN 978 1 78096 319 8 p. 25

[12] Dornberger, Walter, V-2, Viking Press, New York, 1954, Library of Congress catalog card no. 54-7830, p. 5, p. 114

[13] Dryden Flight Research Center - Flight Research Milestones, October 10, 2012 http://www.nasa.gov/centers/dryden/about/Dryden

[14] Dydek, Zachary, Anuradha Annaswamy, and Eugene Lavretsky.“ Adaptive Control and the NASA X-15-3 Flight Revisited.” Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers Control Systems Magazine, June 2010, pp. 32-38

[15] Evans, Michelle, The X-15 Rocket Plane - Flying the First Wings into Space, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska, 2013, ISBN 978-0-8032-2840-5

[16] Frey, Robert L. and Schrenk, Lorenz P., Northern Pacific Supersteam Era 1925-1945, Golden West Books, San Marino, California, 1985, ISBN 0-87095-092-4

[17] Gorn, Michael H., Expanding the Envelope - Flight Research at NACA and NASA, The University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, 2001, ISBN 0-8131-2205-8

[18] Greene, Warren E. The Bell X-5 Research Airplane, Historical Division, Office of Information Services, Wright Air Development Center, Air Research and Development Command, March 1954

[19] Hallion, Richard P., Supersonic Flight - Breaking the Sound Barrier and Beyond - The Story of the Bell X-1 and Douglas D-558 , Brassey’s, London - Washington, 1997, ISBN 1 85753-253-8

[20] Hansen, James R., First Man - The Life of Neil A. Armstrong, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2005, ISBN 0-7432-5631-X

[21] Holder, William G., Convair F-106 “Delta Dart”, Aero Publishers, Inc., Fallbrook, CA, 1977, ISBN 0-8168-0600-4

[22] Holleman, Euclid C, and Boslaugh, David L., A Simulator Investigation of Factors Affecting the Design and Utilization of a Stick Pusher for the Prevention of Airplane Pitch-up, NACA High Speed Flight Station, Edwards, CA, Research Memorandum-H57J30, January 1958

[23] Horne, Derek, The Convair XF-92A, derekhorne.tripod.com/xf92a.html

[24] Jackson, Donald Dale and the editors of Time-Life Books, The Aeronauts, The Epic of Flight series, Time-Life Books, Alexandria, VA, 1984, ISBN 0-8094-3268-4, p. 128

[25] Jenkins, Dennis R., Dressing for Altitude - U.S. Aviation Pressure Suits-Wiley Post to Space Shuttle, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 2012, Washington, DC, ISBN 978-0-16-090110-2

[26] Jenkins, Dennis R. and Landis, Tony r., HYPERSONIC - The Story of the North American X-15, Specialty Press, North Branch, MN, 2003, ISBN 1-58007-068-X

[27] Johnson, Dan, Messerschmitt Me p.1101, Luft ‘46.com website, WW II German Aircraft. 14 October 2000, http://www.luft46.com/mess/mep1101.html

[28] Keillor, Garison, Lake Wobegon Days, Viking Press, New York, 1985, ISBN 0-670-80514-9

[29] Keillor, Garrison “In Search of Lake Wobegon”, National Geographic Magazine, Dec. 2000, pp. 87- 109

[30] Kempel, Robert W. and Day, Richard E., “A Shadow over the Horizon - The Bell X-2”, American Aviation Historical Society Journal, Volume 48, 2003, P. 2

[31] Lewis, Sinclair, Main Street, Harcourt, Brace, and Howe, 1920, ISBN 1420930923

[32] Libis, Scott, Douglas D-558-1 Skystreak, Steve Ginter, Simi Valley, California, 2001, ISBN 0-942612-56-6

[33] Libis, Scott, Douglas D-558-2 Skyrocket, Steve Ginter, Simi Valley, California, 2001, ISBN 0-942612-32-9

[34] Lindberg, Charles A., WE, G. P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, London, 1927, pp. 19-24

[35] Longyard, William H., Who’s Who in Aviation History, Presidio Press, Novato, CA, 1994, ISBN 0-89141-556-4

[36] Matthews, Henry, The Saga of Bell X-2 - First of the Spaceships - The Untold Story, HPM Publications, Beirut Lebanon, 2002, ASIN B009261A9S

[37] McRae, Wallace, Stick Horses: and Other Stories of Ranch Life, Gibbs Smith, Layton, Utah, 2009, ISBN 978-1-4236-0951-1

[38] Merlin, Peter W., Starbuster: 55 years ago Capt. Mel Apt conquered Mach 3, lost life on fated flight, National Aeronautics and Space Administration Dryden Flight Research Center, History Office, 5 November 2011

[39] Miller, Jay, The X-Planes - X-1 to X-31,Aerofax, Inc., Arlington, Texas, 1988, ISBN 0-517- 56749-0 Start of the X-plane program pp. 9-13 Start of the X-1 project p. 15

[40] National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics High Speed Flight Station, Letter to ENS David L. Boslaugh, August 27, 1956

[41] National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics High Speed Flight Station, X-PRESS newsletter, Volume 1, Issue 45, December 28, 1956

[42] National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics High Speed Flight Station X-PRESS newsletter, Extra Edition of October 14 1957 celebrating the 10th Anniversary of Supersonic Flight, p.10.

[43] National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Flight Research Center Staff, Experience With the X-15 Adaptive Flight Control System, NASA Technical Note D-6208, March 1971.

[44] National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Neil A. Armstrong Flight Research Center, Fact Sheet: Bell X-2, Feb. 28, 2014

[45] National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Neil A. Armstrong Flight Rsearch Center, Fact Sheet: XF-92A Delta Wing Aircraft, Aug. 12, 2015

[46] National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Neil A. Armstrong Flight Rsearch Center, Fact Sheet: First Generation X-1, Feb. 28, 2014

[47] National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Neil A. Armstrong Flight Rsearch Center, Fact Sheet: X-3 Stiletto, Feb. 28, 2014

[48] National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Neil A. Armstrong Flight Rsearch Center, Fact Sheet: X-4- Bantam, Aug. 12, 2015

[49] National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Neil A. Armstrong Flight Rsearch Center, Fact Sheet: X-5 Research Aircraft, Aug. 12, 2015

[50] National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Neil A. Armstrong Flight Rsearch Center, X-PRESS news magazine, Volume 56, Number 2, March 2014

[51] Parfit, Michael, Last Stand at Rosebud Creek - Coal, Power, and People, E. P. Dutton, New York, 1980, ISBN 0-525-14357-2

[52] Pearcy, Arthur, Flying the Frontiers - NACA and NASA Experimental Aircraft, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 1993, ISBN 1-55750-258-7

[53] Peebles, Curtis, The Spoken Word: Recollections of Dryden History the Early Years, NASA Monographs in Aerospace History, NASA History Division, Office of Policy and Plans, NACA Headquarters, Washington, DC, NASA SP-2003-4530, 2003

[54] Ransom, Stephen and Cammann, Hans-Hermann, Me 163 Rocket Interceptor, Classic Publications, Ltd., Crowborough, England, 2002, ISBN 1-903223-13-X

[55] Sanderson, Kenneth C., “The X-15 Flight Test Instrumentation”, NASA Flight Research Center, Edwards, CA, Proceedings of the Third International Symposium sponsored by the Department of Flight, College of Aeronautics, Cranfield, Pergamon Press, Oxford, 1964, Library of Congress Catalog Card N0. 61-17510

[56] Stilwell, Wendell H., X-15 Research Results, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Washington, DC, 1964, NASA Special Publication-60

[57] Taylor, Michael j. H., Jane’s Encyclopedia of Aviation, Crescent Books, New York - Avenel, 1989, ISBN 0-517-10316-8

[58] Thompson, Milton O., At the Edge of Space - The X-15 Flight Program, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC, 1992, ISBN 1-56098-107-5

[59] Tomash, Erwin, “The Start of an ERA: Engineering Research Associates, Inc., 1946-1955,” in A History of Computing in the Twentieth Century, N. Metropolis, J. Howlett, and Gian-Carlo Rota, eds, Academic Press, Inc., New York, 1985 pp 485-495, ISBN 0-12-491650-3, p. 491

[60] Tremant, Robert A., Operational Experiences and Characteristics of the X-15 Flight Control System, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Flight Research Center, NASA Technical Note D-1402, 1962

[61] Tucker, Charles, Flight Testing The Northrop X-4 Bantam: A Tailess Transonic Experiment, Air Age, Feb. 2002

[62] University of Minnesota - Institute of Technology - Department of Aeronautical Engineering, Aeronautical Research Facilities, Research Report 105, Minneapolis 14, Minnesota, 1954

[63] Western Energy Company - A Westmoreland Mining LLC Company, Rosebud Mine Tour Fact Sheet, June 2007

[64] Wickipedia, the free encyclopedia - Alexander Lippisch, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Lippisch

[65] Wickipedia, the free encyclopedia - Bell X-2, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bell_X-2

[66] Wickipedia, the free encyclopedia - Bell X-5, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bell_X-5

[67] Wickipedia, the free encyclopedia - Convair XF-92, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Convair_XF-92

[68] Wickipedia, the free encyclopedia - Douglas D-558-II Skyrocket, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Douglas_D-558-2_Skyrocket

[69] Wickipedia, the free encyclopedia - Douglas X-3 Stiletto, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Douglas_X-3_Stiletto

[70] Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia - Langley Field, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Langley_Field

[71] Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia - Lockheed F-104 Starfighter, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lockheed_F-104_Starfighter

[72] Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia - Lockheed P-38 Lightning, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lockheed_P-38_Lightning

[73] Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia - Messerschmitt P.1101, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Messerschmitt_P.1101

[74] Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia - North American F-86 Sabre, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North_American_F-86_Sabre

[75] Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia - Northrop X-4 Bantam, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Northrop_X-4_Bantam

[76] Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia - Reaction Motors, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reaction_Motors

[77] Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia - Reaction Motors XLR11, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reaction_Motors_X

[78] Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia - Republic XF-91 Thunderceptor, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Republic_XF-91_Thunderceptor

[79] Wilkinson, Stephen, “The 98-Pound Weakling of Research Airplanes”, Smithsonian Institution, Air and Space Magazine, July 2014

[80] Yeager, Chuck and Janos, Leo, Yeager, Bantam Books, Toronto, New York, 1985, ISBN 0-553-05093-1