Oral-History:James Boyd

About James Boyd

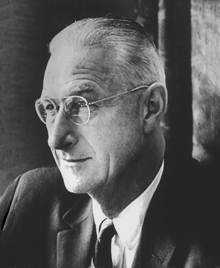

James Boyd began his professional career at 36 years of age as field engineer with Radiore Co. From 1929 to1941 he was on the faculty at Colorado School of Mines where he became associate professor and later, (1946-1947), dean of faculty. During World War II he served in the War Department, aiding in mobilization of the mining industry for the war and then helping direct the flow of raw materials to the military production program. He next served as the first director of the Industry Division of the Military Government in Germany. From 1947 to 1951, Boyd was director of the U. S. Bureau of Mines, and during part of that period headed the Defense Minerals Administration.

In 1951 Boyd returned to industry as exploration manager for Kennecott Copper Corp. From 1955 until 1960 he was vice president-exploration. He has been president of Copper Range Co. since early I960.

Further Reading

Access additional oral histories from members and award recipients of the AIME Member Societies here: AIME Oral Histories

About the Interview

James Boyd: An Interview conducted by Eleanor Swent in 1986, Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1986.

Copyright Statement

All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between the University of California and James Boyd dated September 4, 1987. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley.

Request for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the Regional Oral History Office, 486 Library, University of California, Berkeley 94720, and should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user.

It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows:

James Boyd, "Minerals and Critical Materials Management: Military and Government Administrator and Mining Executive, 1941-1987," an oral history conducted in 1986 by Eleanor Swent, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1988.

Interview Audio File

Interview

INTERVIEWEE: James Boyd

INTERVIEWER: Eleanor Swent

DATE: 1986

PLACE: Berkeley, California

[Date of Interview: October 17, 1986]

Swent:

This is Friday, October 17th, 1986, and we're in Carmel, California, at Del Mesa Carmel. I'm Eleanor Swent and talking with James Boyd in his study. First, you might just briefly tell about some of your distinguished forebears and how you started in the mining world.

Grandfather. Lewis Henry Boyd, Advisor to Herbert Hoover

Boyd:

My father was the son of a Sydney [Australia] stockbroker who moved to the London stock exchange about 1896.

Swent:

From Sydney, Australia?

Boyd:

From Sydney, Australia. While he was in the stock exchange, both in Sydney and London, he used to help Mr. Herbert Hoover, who later became president of the United States, to finance his mining ventures all over the world, in Australia, in China, and in Borneo and places like that.

Swent:

Had they met in Australia first?

Boyd:

I don't know. I don't know whether they had met before.

Swent:

I was wondering if Herbert Hoover went to Australia because of any connection with your grandfather?

Boyd:

Probably. But more likely he would have gone to Australia because he had gene to England and become a member of a consulting firm there. In those days, consultants like Mr. Heaver or John Hays Hammond and people like that were expected to put their own money into the ventures they recommended. Today it would be considered to be unethical. Probably because the system got abused by unethical men. It was a pretty good idea. It made them careful what they did.

Swent:

You thought it was a pretty good idea that you cannot do it new?

Boyd:

No. that you could do it then. I mean, if you were going to go out and recommend an operation, you'd be more likely to have people put the money up if they saw your money in there.

Swent:

In other words, if you thought it was a risky venture, and your own money was in it, you would be less apt to recommend it?

Boyd:

That's right.

Swent:

Why has the opinion on that changed?

Boyd:

Well, it's because people are afraid that people cannot be particularly honest and do something besides. The result is that the law kind of makes it difficult for an insider to have an advantage to what he does. When I went to Copper Range Company, I was given stock options to make me want to change my job, to go with them. That still made you a part of a deal so you earned your way.

I've heard of great people that went through and didn't get paid any salary at all. I think the great one of those is the present president of the Chrysler Corporation, lacocca, He wasn't paid a salary. He had to demonstrate and earn his way as president of the company. So I can never understand why it is the wrong thing to do. That was how many of these people, like Hoover, Mr. Hoover, and John Hays Hammond, and others, made their fortunes by the ventures that they established [and] operated for the people who put the money up for it.

Father. Julian Boyd. Mining Engineer in Australia

Boyd:

Anyway, that moved my father's family back to England, and they settled in Surrey. Dad then went to the Royal School of Mines in the Imperial College in London. He had no degree from it, but he was just merely a fellow of the Royal School of Mines. Mr. Hoover then sent him to Western Australia, because this was the beginning of the gold rush in Western Australia, which was the second gold rush. The first gold rush was in Victoria, and the prospectors were digging holes all over the place. Each one was given an allotment of land and he had to dig for the gold on that little plot of land. That's why the Australian soldier was called a digger.

Swent:

That was in eastern Australia?

Boyd:

Southeastern Australia. It was in Victoria.

Swent:

And that was shortly after the California gold rush.

Boyd:

Yes, that was just a little bit after the California gold rush.

Swent:

And then the Western Australia gold rush

Boyd:

Was later. It was about in the 1890s. Dad must have gone there about 1898.

I've been thinking about the fact of the timing, because Mr. Hoover sent him out to Australia. He had in the meantime met my mother. He had a friend out in Western Australia when he went out there. This friend had a lady friend that he was thinking about getting married to. He sent for her, and my mother went along as a sort of a chaperone.

Swent:

From England?

Boyd:

No, from Melbourne, Australia, because Mother came from a Melbourne family. She was sort of a chaperone when she went out there. This other man got sick, and he sent my father along to meet these two girls that came up on the train from Perth. Remember, there was no train running across Australia then.

Swent:

I was going to say, how did you go from Melbourne to Perth?

Boyd:

You had to go by ship, and a sailing ship at that, around the south, across the Bight, and into Fremantle. Then they took a train from there up to Kalgoorlie. In my day there was no train from Kalgoorlie eastward to Adelaide.

Swent:

No, that's fairly new, that Nullarbor train.

Boyd:

Well, it was soon after that, though. It was a weird thing because each state it crossed used different gauges.

Swent:

You could go straight through across Australia now.

Boyd:

Yes, that's right. Clemmie [Clemence DeGraw Jandrey Boyd, the second Mrs. James Boyd] has been on that train.

My father was in the Kalgoorlie area, There's a little town called Kanowna, which is twelve miles east of Kalgoorlie, where Dad was doing some development work on mines. They went there about six months after they were called back from southern Rhodesia. Hoover had sent them to southern Rhodesia to work on some mines over there and then transferred him back to Australia. Six months after they got back to Australia I was bern. I always considered that I was conceived in Zimbabwe and bern in Australia.

Swent:

Did your mother just stay on or go back to Melbourne?

Boyd:

No. no. She stayed right there, and the doctor that came to deliver me was so dirty that she wouldn't let him touch her. She had had some hospital experience. Her mother had died in childbirth with her sister. Then her father remarried a governess. The family didn't like her very much, so my mother ran away from home and went to become a nurse. That's where she had had training. So she knew how to deliver babies and she did it by herself rather than have somebody else do it that she didn't trust.

Then my brother was born, Lewis Henry Boyd, named after his paternal grandfather. We always called him Bill. He's known throughout the industry as Bill. He was born in a town called Menzies. Now, Menzies is a famous name in Australia, Since then there's been a prime minister named Menzies. But the Menzies were well known, and this little town was about sixty or seventy miles north of Kalgoerlie.

My father apparently was overseeing prospects, sinking shafts and seeing whether they were prospective mines or not. That's one of the ways you operate in the mining business. You get a prospect and you dig a little bit on it to see whether there's any geological reason. Then if you get encouragement, you sink shafts or whatever you need to do. That had to be done before you could prove there was an ore body there that was worth developing.

About this time, by 1907, he was moved to Boulder, which was a town adjacent to Kalgoerlie. He was made the manager of the Chaffers Mine, which was an established gold mine.

Swent:

Was your grandfather still in London?

Boyd:

Yes. I don't know much about that family's history. Of course, we got to know them when we moved to England later.

Swent:

I was just thinking it must not have been easy to communicate back and forth between Kalgoorlie and London.

Boyd:

No. I don't ever remember any communication at all.

Swent:

You wouldn't get much direction from your head office, would you?

Boyd:

Well, they had to do it by mail. That went by steamship, and there were not many steamships*

Swent:

But the man on the property had to make a let f decisions.

Boyd:

Absolutely. I saw a letter once that Mr. Hoover wrote in reference to that in which he obviously had a let of confidence in him. He would take his advice. He was operating this gold mine as early as I can remember.

When we were in Kanewna I was three years old. I fell down a mine shaft seventy-five feet deep. They apparently had been feeding tailings, ground rock, into this thing, and I had gone out walking with my little dog. We were pushing tailings into the hole, and apparently we undercut the thing. The dog tried to go with me and we went down it. He was down in the shaft with me.

They hunted for me all day, then finally they heard the dog barking down there and Dad came down. My earliest recollection is Dad carrying me up the ladder with a candle in his hat. I don't remember falling down; I don't remember anything before that. But I distinctly remember being carried up that ladder with that candle in his hat.

Later on, as I get a little older, and Father was going to the mines on Saturday, he would take me along with him. I went underground with him in the gold mine. Chaffers Mine. I can remember those occasions very well.

Swent:

From childhood, really.

Boyd:

From childhood, yes. We wore candles in our hats in these days.

They allowed something they won't allow today, and that's blasting in the mine while people are still in the mine or anywhere near the blast. One occasion I remember, we were on one level. They were blasting the level below, and it blew our candles out. We were suddenly all in the dark and we had to relight them. I don't remember being frightened by that either.

My first what would you call it an exposure to death, was to see a donkey, a dead donkey by the tailings pond of the mill. I remember asking Dad about that, and he said, "Well, he had probably been drinking the cyanide solutions."

Remember, gold is soluble in cyanide. It was used in those days to recover gold, and apparently the donkey drank the effluent. So I always remember that cyanide provided my first occasion to visit death. I think there's a better word than that, but that's all right for now.

Swent:

I do want you to mention your mother's family.

Boyd:

My mother's maiden name was Cane. Her grandfather sent her father and his brother out to Victoria with eight thousand pounds. And remember, eight thousand pounds back in the 1880s was a lot of money. They bought something like a million acres of land, the kind of land where it took ten acres to run one cow, I think. But it was around Ballarat. That was where the famous first gold strike was in Australia.

Their home was near Ballarat. What happened to that land 1 don't know, but when my grandmother died and the governess who became his second wife took him off to see the bright lights in England, they had to go by sailing ship, and they were gone some months. While they were gone one of those great droughts came along and pretty well wiped them out. I don't have much knowledge about that, although I have four cousins still living in Melbourne, and we visited last summer, our winter. They've given me a lot of that information and I really haven't studied it very far.

Mother was born in England because the family was visiting England when she was born. She was born in a town called Felixstowe, the home of the Allenbys. They must have been staying there because the Allenbys were there. Mrs. Allenby was an aunt. That was Field Marshal Lord Edmund Allenby's mother, whom I met when we were in England. We went down to visit her. She was a very wonderful old lady.

Swent:

What was his claim to fame?

Boyd:

His first claim to fame was leading the retreat from Mons in the First World War. A retreat is the most difficult military operation, and he successfully retreated from the Germans in Mons into France. He is best known for his conquest of and the liberation of Palestine from the Turks. (I have pictures of him walking into Jerusalem rather than riding his horse as a conquerer.)

Swent:

And the Allenby Bridge is there.

Boyd:

Yes. Allenby Bridge was built in memory of him because he was pretty thoroughly appreciated by the people. I've got Lord Waverly's, Viscount Waverly's book here on Allenby in Egypt. He describes the character that Allenby was. He was a pretty tough soldier, I guess. I remember when he came out later in between the wars to California he called on my mother. My father called her Molly, but he called my mother Mary. He said, "Mary, they want me to plant a tree in the forest of fame in Hollywood." He was tickled about that.

Boyd:

I never get to meet him. I met his mother but I've never met him.

He was a great friend of Sir Robert Baden-Powell, the founder of the [Boy] Scout movement. It was Allenby's son that named it that, because the two great friends were out riding horseback, and they came back and his son was up in a tree. He said, "Pew, pew. pew. You didn't send your scouts out, so you're dead." He was killed in the First World War.

That sparked Baden-Powell to call it the "Boy Scout" movement. Somewhere Mother kept a cutting of that in the newspaper. I haven't found it again. I haven't thrown that kind of stuff out, so someday I might find it again.

Swent:

Has your family been active in Boy Scouting, then?

Boyd:

Some of them were. I had only one brother; he was not. My eldest son was an active Boy Scout. My third son was a Sea Scout, but my second and fourth sons had no such use for such activities. The Sea Scout's son is an Eagle Scout and is going to a Jamboree in Australia in 1987-88.

Swent:

You weren't a Boy Scout?

Boyd:

Yes, I was a Boy Scout. sure. But don't forget, when I was a Boy Scout it was an embryonic movement. This is when Baden-Powell was still getting it started. We weren't as well organized as they are today. We would go out on camp trips. I remember once I camped on the Swan River in Perth and I got a good sunburn. I walked home and I had sixpence in my pocket. The cab driver drove me as far as he could take me for sixpence, and I had to walk with my pack on my back, back to the house on Cot to sloe Beach.

Swent:

You were living then in Perth?

Boyd:

Well, we always spent the summers there. Dad built a house on the beach in Cottesloe Beach, which is a suburb of Perth. He sent us down there. In those days it was just beautiful, rounded white sand dunes on the Indian Ocean and no houses except the few, the one we lived in and two others. There was a little hotel down there, Cottesloe Beach Hotel, but new there's a golf course where our house was, I think. It was my memory as I went back on this recent (1986) trip. We drove along the front and I'm pretty sure that the golf course now is where our house was. Of course, this is where the yacht race will be held, in sight of Cette sloe beach in February, 1987.

Swent:

America's Cup.

Boyd:

Yes.

Swent:

Did you go to school in Australia, or did your mother teach you?

Boyd:

Well, since we would go down to Cottesloe Beach in the middle of summer to get us out of the heat of the desert, we would be put in school in Perth. I went to Canon McClement's School. It was in a kind of an old baronial-looking building, and I'm pretty sure I saw it when I was in Perth last February, 1986.

Swent:

Were you Anglicans at that point?

Boyd:

Oh yes. The men of my mother's family were either sailors (an uncle was first hand of the Admiralty, Churchill's boss in 1914), soldiers like Allenby (I think that there were about seven fatal casualties in World War I), or Anglican ministers. The picture referred to is the one hanging in my study of Grandfather with his five sons. From left to right, back row: Jack, who lived the longest, was bombed out of his lodgings twice in World War II; Sol, who was a surgeon on Harley Street; Arthur. Front row left: Julian; Grandfather Frank who was on the Stock Exchange and had the only other children. Budge and Audrey.

We became Christian Scientists because my father's youngest brother who is in that picture got very ill and he was healed in Christian Science. That impressed Mother and Dad so much that they took up the study. I don't remember when I wasn't a Christian Scientist. There weren't many Sunday schools around to go to so they had to give us Sunday school themselves. But there was a Sunday school in Kalgoorlie and there was a Sunday school in Perth, and plenty in London.

Swent:

Christian Science?

Boyd:

Christian Science. The church that we went to in Perth last February has been built since then, so it wasn't the same church, but it was the same organization.

While Dad was in Rhodesia, it was the end of the Zulu wars. They required that all of the Europeans be taken into the armed forces, so he was a trooper with a commission in the British Army.

Swent:

This is before you were born?

Boyd:

Yes, that's before I was born. But in 1914 when Australia joined the rest of the Commonwealth with England when England had declared war, he was called up immediately. That would be 1914. We went to the camp to see him before he left, and we watched him get on board the ship.

There's a book new out, and I don't have a copy of it here. It's called A Satisfactory Life. It's the story of a poor man. a youngster, who was really enslaved in the agricultural zone between the deserts where we were and the coastline. They had farms and wheat fields and cattle and things like that. He had never gone to school at the age of fourteen, and his education came from getting some help in reading and just reading from there on. In his eighties he wrote this book. It isn't a great masterpiece of literature, but it's a fantastic description of what his life had been. He joined the Australian forces back in 1914 and was wounded in Gallipoli, Dad, of course, was taken in [at the same time].

Swent:

Was your father at Gallipoli?

Boyd:

He was wounded at Gallipoli, too. Not only that, but they were in the same battalion, 11th Battalion. I don't knew whether they knew each other or not . Dad was a commissioned officer and I think the man who wrote this book got to be a sergeant in along the line.

Swent:

I've only been to Australia once, and only stayed for a month, but no American can realize until you really go there, I guess, how strongly that Gallipoli memory lives in Australia.

Boyd:

A lot of Australians died there. It was murder.

Swent:

It was just an appalling thing.

Boyd:

Somewhere in my papers or our papers was a description. I don't know whether Mother saved it or not . I haven't found it since she passed on. A fellow wrote an article in the newspaper describing what my father had done in that campaign. They had captured a Turkish trench, and the Turks were counterattacking. Dad had only five or six men in his company left. They had boxes of grenades and they would run back and forth and throw these grenades out from various places to make the Turks think there were a lot of people there still. One time when he came back to a box. a Turkish grenade came into the trench. Dad pulled a sandbag down on top of it. and blanket on top of that, and sat on it. It went off. He remembers pulling up his trousers while the fighting was still going on. When it quit he looked down and he had got a piece of bomb through his knee and he was wounded. They relieved him and took him to Egypt.

About that time they decided to move us my mother, my twin sisters, and my brother to England. We took ship from Fremantle, and went through the Suez Canal. We had on board the Viceroy of India, so they gave us a destroyer escort when we get into the Mediterranean.

One day I remember clearly the destroyer was over on the pert side, and suddenly a noise came. There were all kinds of sirens and whistles, and she took off. You could see that plume off the bow of that ship. Then we heard gunfire. A German submarine was trying to sink us. This destroyer went up and sank it. We heard about this later. This so scared so many people that when we get to Marseilles a let of people left the ship and took trains across France. The Germans hadn't intercepted that yet. Then, of course, the channel to England. But we stayed with the ship.

Swent:

Wasn’t the war in France by that time?

Boyd:

Oh yes, in the northern part of France. You could get across still and across the English Channel. But we stayed aboard. A week or ten days after we got off, she was blown up either by a torpedo or a mine I never knew which and was sunk off the coast of England.

Swent:

Now you were what, about twelve, eleven?

Boyd:

This would be 1917, so I was thirteen, wasn't I? No, I would be twelve.

Swent:

It's interesting that they would move civilians through war zones, really.

Boyd:

I can't answer that question for you. I don't know where they went, but there was no war in southern France, Marseilles. The Germans were still up around Verdun and places like that north of Paris. So they could come in and go up and across the channel at Cherbourg without getting into the war zone.

Later on Dad went to France and did some fighting there, but he was called back. I think his leg was giving him trouble still, and he was called back to England and became the President of Court Martial for all the Australian troops in England. When the boys were a little wild they would get court martialed, and he had to run the court.

Swent:

Was this your first time in England?

Boyd:

No. My parents went to England when I was about one or one and a half. I was christened in Harlech, Wales. Later on, when John L. Lewis, the one who picked on me, you know I'll tell you about that later. I knew more about Wales than he did, and he considered himself a Welshman.

Swent:

You were a real man of Harlech?

Boyd:

That's right.

Swent:

Why did you go to Harlech?

Boyd:

Well, because my mother's eldest sister and her daughter and her husband met us in Wales, and my cousin and I were I don't knew whether she was christened there or not. Anyway, my aunt was living in Kenya. They were some of the first white settlers in Kenya. They went there before 1914. Have you seen the picture called the

Swent:

"Flame Trees of Thika?"

Boyd:

"Flame Trees of Thika," yes. I'll tell you a little more about this in a minute. But this was interesting to you?

Swent:

Yes. it is.

Boyd:

They lived south of Thika, Kenya, but not very far. They settled there and grew tea and coffee. But my uncle got called into the war, and my aunt then had built little cabins around to house people who were escaping from the danger zone, and they really liked it so much that they started coming back, and she had to start charging. So she made it what she called a hotel. Anyway, she brought her daughter to England and I was christened there, and I think Margo, that's her daughter's name, is still living, and we went to visit her when we went on the 1986 trip. She said she's vastly older than I am. I think it's six months or something like that.

Swent:

Where's she living now?

Boyd:

She lives in a house that her mother built outside the "hotel" grounds for her family. The installation consisted of a central eating and meeting hall surrounded by cottages. Her daughter had to sell it some time ago. She and her husband lived in it after Aunt Violet Cane died.

She was an only child, and she had only the one daughter that still lives there. She's married to a man who is managing director of a tea and coffee company and they have three daughters. So they produced no male children at all.

Swent:

How long were you in England then?

Boyd:

We went to England in 1917. I was put to school, prep school, in Surrey, in the same town, Kenley, where my grandmother, my father's mother, lived. They lived on a beautiful estate. A Roman road ran through called the Hathe. It was there that Mr. Hoover came to visit my grandfather when he wanted to raise money or for arrangements that he had to make, to do his work all over the world.

Swent:

And you also had uncles who stayed in England?

Boyd:

Yes. Oh yes. they were all there. All five of those Dad was of course in the army but those four brothers were alive then, [indicates a photo on the wall]

Swent:

And they all stayed in England. He's the only one who went off to the colonies?

Boyd:

Yes. I guess so. Yes, because Uncle Frank and Uncle Jack were with their father's concern. The eldest brother was a doctor on Harley Street. I don't know what Arthur did. He wasn't very well. You can see in the picture he wasn't very strong.

Swent:

Did you feel that you were sort of an outlander, or colonial?

Boyd:

No, I don't remember feeling that. Actually, I stayed in Uncle Frank's house, and he was the only one, besides Dad, who had any children. He had a daughter and a son. That son, Budge, became a foreign service officer of the British Foreign Service, and he married an actress, a very lovely lady. But they never had any children. The daughter Audrey had a boy and a girl, and they moved back out to Australia later on. I never knew them at all. Budge was sent to California and was a consul in Los Angeles, so my twin sisters got very close to them. I was in Colorado in those days and never saw him.

Swent:

Do you remember, when you went back to England did they tease you about they way you spoke, or did you have any difficulty being an Australian?

Boyd:

No. I don't think so. I still have a lot of Australian in me. Of course, besides those four brothers. Dad has three sisters, and they were home. One of them was married to a naval officer, and she lived there with her mother. So I used to go visit them on Sundays, the three, Chill, and Bess, and Violet. Violet was the wife of the oldest brother. They very carefully knocked my Australian out of me [starts speaking with an Australian accent]: "My English aunts knocked the Australian out of me." [resumes his normal accent] Most of it. I still have some of it. If I'm aware of it, I don't know it. You automatically correct those things which you hear.

Swent:

You don't have too much left.

Boyd:

But people recognize it.

Swent:

I noticed you said your mother had a cutting; I would say a clipping.

Boyd:

Yes, that's right.

Swent:

That's English.

Boyd:

Yes. I've got to use some Australian expressions.

Swent:

That's all right. That's nice.

Boyd:

Anyway, we went there, and I was put in prep school it's called prep school there, which is grade school, private grade school in the town where my grandmother lived, so I could go home to her house on Sundays and play croquet or chess with her.

Swent:

But you were boarding during the week?

Boyd:

Oh yes, I was boarding in the school. I was there throughout the rest of the war. When armistice was declared I was sent to put up the British flag. I put it on upside down. That's how I remember that. [laughs] From there I was then admitted to one of the English public schools called Oundle. That's in Northamptonshire, in the town of Oundle just south of Peterborough.

Swent:

That's quite a ways away from Surrey.

Boyd:

Yes. Mother had a flat in London, and during the time that Dad was President of Court Martial he could come home on the weekends and be with her. I was at Oundle, and my twin sisters were at a girls' school called Bedales. I don't know where brother Bill was. He went to school somewhere else.

On holidays we would stay in the flat and go and visit the museums all over London, and so forth. But we went to Sunday school in the First Church of Christ Scientist where Lady Asquith later on would be. She used to be a member. So I spent then, I guess, a year and a half at prep school in Surrey, and then I spent three years in the public school at Oundle, although I didn't graduate there. In the meantime Dad was being demobilized from the army and was hired to run the borax mines in Death Valley.

Swent:

It was from London then, that he came to America?

Boyd:

Yes. Borax Consolidated was a British firm. One thing, they wouldn't trust the American mining engineers in those days, and they had to have a Britisher. That's how he got sent over there to run that.

Swent:

Did James Gerstley come over then, or later?

Boyd:

Later on. But that was when Dad was retired. They retired him, and kept him on as a consultant. They paid him his salary as long as he lived. But that's another story. He had quite a story of being up there.

Boyd:

Mother came over to see whether or not we should migrate. Then they decided that we would move to Hollywood and Dad could come down over the weekends or once or twice a month to see us.

Swent:

This would be your senior year in high school?

Boyd:

No, the end of the junior year. I would have had another year in the English public school.

Swent:

That's sort of a hard time to move, isn't it?

Boyd:

I suppose so. but I don't remember it being much. It was quite an exciting thing, so it never bothered me. I remember we came ever on a very stormy sea. Everybody was sick but us.

But there were a whole lot of reporters aboard. When we got to New York, immigration authorities came aboard and said that we were Australians, and the Australian quota was filled, and we couldn't land. But Mother was born in England, and the English quota wasn't filled, so she could land. Well, the reporters took this up. Here were these wonderful children. They got people down in the hold, all the riffraff of Europe they were letting in, and they couldn't get this wonderful family in. So they made a fuss about it.

We walked down the street with our little English caps on, the four of us. and they took pictures of us and they had it on the front page of the newspapers. Dad didn't hear anything about this. Someone handed him a newspaper in Los Angeles saying his family had been held up. Anyway, the company, the borax company's lawyers got after this back and forth from Washington, and they finally got us admitted as students. We were then put on the subsequent year's quota. That's how we got admitted.

Swent:

How did your father get in? Did he have any trouble?

Boyd:

No. Apparently his company worked him in somehow. Probably that quota wasn't filled when he went in.

Swent:

He didn't anticipate this problem at all.

Boyd:

No he didn't. They were about to send us home. Then the reporters really raised Cain.

Swent:

So you went to Hollywood High then?

Boyd:

Dad in the meantime rented a house in Hollywood and I went to Hollywood High School and finished in a year and a half. We arrived in December of 1921, and I graduated in 1923.

Swent:

That was the heyday of Hollywood. I guess.

Boyd:

Oh sure. A fellow by the name of Joel McCrea was a classmate of mine, and he became a great star. Here was a green English schoolboy who when he went to school, his schedule [pronounced "shedule"] was made out for him. and he did what he was told. I got down there and I made my own "skedule" out. Joel helped me make my schedule out and went to class with me, the English class, I remember. I've never seen him since. He's still living, and he did very well. He was acting until recently.

Swent:

He was a fine actor.

Boyd:

Yes.

Swent:

This must have been pretty exciting for you.

Boyd:

Yes, I think so. Dad bought me a bicycle. I had to ride a bicycle through downtown Hollywood. You wouldn't dare let a child ride through Hollywood today on a bicycle.

Swent:

That was really the beginning of the golden age of film, wasn't it?

Boyd:

That's right, sure. After we had been there less than a year Dad bought a house up on the hill. You know where the "HOLLYWOODLAND" sign used to be, now it reads just “HOLLYWOOD.” For a brief time in 1987 the people got up in the morning to read "CALTECH." Well, on one of these ridges down below that they bought a house. I used to ride a bicycle down there to Hollywood High School. Bill went there too.

My sisters went to grade school down on Franklin right below. Then they went along to Hollywood High School and up to UCLA. But they were six years behind me.

Swent:

The twin girls?

Boyd:

Twins. Yes.

Swent:

Were you thinking by now of becoming a scientist, or going into mining like your father?

Boyd:

Yes. Dad tried to keep me from being a miner. He said, "There's no way you're going to be a mining engineer." But I wanted to be an engineer. I'd been enough around it that I wanted to be an engineer. I found that I was good enough at mathematics. So I decided that the only place to go would be to Cal Tech [California Institute of Technology].

Swent:

You had really not had much contact with mining except

Boyd:

Except through Dad, none.

Swent:

No. You were going to school in Perth.

Boyd:

Well. no. We went back. During the winter months we were in Kalgoorlie, or Boulder, so I would frequently go with my father down to the office. One day I went down to the office and we had a horse-drawn two-wheeled sulky, it was called. The horse tripped just as we were coming into town and threw Dad out. The reins went with him and I couldn't reach the reins. He bolted through Boulder, missing the street car poles by inches. At the far end of town an abe [aborigine] on horseback tried to save me. but he got in the way of the horse turning a corner to take us to the stable, which he would have done, and turned the cart over, and I landed on my elbow on the steel rim and broke it. Oh, I was a hero.

Swent:

Did you ever work in the mines in the summer?

Boyd:

Oh no. See. we left there in 1917, and I was only thirteen years old.

Swent:

So you didn't have any first-hand experience at mining at that point?

Boyd:

No. I didn't have any mining experience until the summers at Cal Tech. or the last summer at Hollywood High School. Then I would go up and stay with Dad at the mines, and he would get me a job as a mucker, or a miner, or a mechanic or blacksmith, or a machinist. They taught me how to be a plumber and every kind of thing. I had to learn how to drive a truck. Have you ever been to Death Valley?

Swent:

Yes. Not for a number of years.

Boyd:

Well, you've been there since the hotel was built down there?

Swent:

Yes.

Boyd:

Well, it wasn't there then. There was a ranch there then, and there were Indians there. We built an Indian schoolhouse, and one summer I drove a truck down there taking the materials for that Indian schoolhouse. As you probably remember, there are date palms there. My mother planted these date palms, and they had to be grafted in order for them to bear dates. She raised these palms from seeds and planted them down there.

Swent:

Your mother must have been a very flexible woman.

Boyd:

She was a wonderful woman. Let's go back a little bit if that's interesting to you. When we were in Rhodesia she was the only white woman within five hundred miles. She carried a whip in her hand and a pistol on her hip. I don't know how true this story is. but if she didn't wave that whip at these boys, they would think she didn't love them very much. They expected to be treated harshly. I'm sure she was tee mild to do that.

Finally one of the other engineers up there sent for his wife and Mother went down to meet her towards Bulawayo. At the top of the pass they were supposed to meet the husband of this other woman. He got there drunk. They put him in the back end of the wagon and sat up on the driving board. They were surrounded by baboons all night long until he got sobered down so he could drive them back down to the mine.

Then she tells the story how she was in the house provided for her and one day she saw a black snake coming, a great big one. These snakes are pretty poisonous in Africa. She jumped on the table and started screaming. Dad got there and here was the snake climbing up the leg. He had to shoot it.

Then on their way up to Bulawayo, where the mine was they went there on their honeymoon, you see. They were married in Australia and they went out to this assignment in Africa. She had all her trousseau in one of these round top trunks, and it was tied on the back of the wagon. When they get to a place to stay overnight, they found the trunk had gone. He went back two days' journey and never found it. So all the silver and everything else that she was getting as a bride were gone and she had to start from scratch. The only thing she had was Mrs. Beaton's cookbook. Have you ever seen Mrs. Beaton's cookbook?

Swent:

No, I haven't.

Boyd:

It's this big, six inches thick, and all designed on how you could feed thirty-eight people for dinner. It had these beautiful colored pictures. Somewhere I've got it. I haven't thrown it away. And she had never cooked in her life.

But she did when she got to Bulawayo, she had to cook. I think she became a good cook. She had to feed us the rest of her life. Her arm was strong enough to beat up a plum pudding. That's pretty stiff.

Swent:

So I guess Hollywood didn't hold many terrors for her after all she had been through?

Boyd:

No. The worst terror she had was going down to buy meat. She would say to the butcher, "Now I want this joint or that joint." They would all laugh at her and didn't pay attention.

Finally one took her and he said. "Now madam, we don't use these words here. This is what we call this, what we call that." She never went to anybody else ever again. She always went to that butcher. Some day he had five or six butcher shops that he had earned by being a good salesman.

Swent:

So you did go out then and see what the mining was all about.

Boyd:

Yes.

Swent:

Was the borax mine an open pit operation?

Boyd:

No. Heavens no. It was underground mines up in Ryan. Originally, of course, borax was mined out of the lakes in Death Valley. The twenty mules went out there and brought it back. That was the story, but it never worked very well because they could never take enough water to supply the mules, and half the mules were horses. Because of all the hay they had to have, there wasn't much room left for borax.

Swent:

There was a little hype even then, wasn't there?

Boyd:

Yes. [laughs] So by the time Dad got there they had built the railroad from Death Valley Junction up to Ryan, where the veins of borax were. That's where he was when he took over. I would go and stay with him in the summertime and I was taught to be a mechanic. I was even taught how to weld and take care of the electrical equipment and things like that. Furthermore, at both the school in England and at Cal Tech, I had to take shop. I spent a whole term in England in the shops learning how to shoe horses, how to weld things, how to do carpentry, how to make patterns for making castings, and things like that. The whole term was really spent entirely in the shops.

Swent:

And you enjoyed that?

Boyd:

I think I did. Then when I went to Cal Tech we had to spend one summer in the shops. They don't do that today. Modern engineers are not taught to do anything with their hands. They're just theoretical characters, I guess.

Swent:

Do you remember anything about your high school teachers that interested you?

Boyd:

In England?

Swent:

Either place.

Boyd:

Well. yes. I remember them very well. In England we lived in "houses." I lived in Crosby House. The housemaster was a fellow by the name of Walker. He was an English master. There's a poem called "The Wreck of the Hesperus" I can't remember who wrote it but the expression was, "Ho. ho, the breakers roared." He despised it, so we called him "Ho, he." He would sound just like this.

The housemaster for the schoolhouse there were six or seven houses was my chemistry teacher. Anyway, I put a flame near where I was generating some hydrogen and I got an explosion. I can never forget the day when he got me by the wrist and he taught me that you don't put flames near hydrogen and things like that. He grabbed my arm and that hurt. I can remember that very well.

Swent:

It actually hurt your arm?

Boyd:

Yes, but not permanently. He was frightened, of course. I expect. They still used corporal punishment there, and the prefects were authorized to punish people. I left my handkerchief out in the change room while I went to play football. I had come out of the dining room at night. We had gas lights then in these days. I would see a prefect standing in the light, and as you came by to go into the commons room, you were sent into the change room. "You left your handkerchief out. Six." You bent over and they would whip the cane smartly across your rear end.

When I went back some years later I learned that they don't do it anymore. I think that's a great shame. I don't think it hurt me a darn bit. It hurt, sure, but I don't think it did me any harm.

The worst thing in prep school that happened to me was when I took the common entrance examinations to get into public school, the housemaster stood over me all the time I was there, and he abused me terribly. "Oh you stupid character," or something like this. And he said, "You couldn't possibly pass all the examinations." And so on.

So I thought I was the stupidest character in the world. It didn't make any difference to me that I got admitted for some reason or other into Oundle school. It was always, "That was because your father was an army officer. You got influence to get in." Or something like that. Every Monday morning, everybody met in the great hall that still exists there. I'll show you a picture.

Swent:

This is at Oundle?

Boyd:

Oundle. The headmaster would stand up on the platform and the top boy in each class would take up the lists. You have to walk up and hand the headmaster the lists. I got my share of these pickups, so it just didn't occur to me that I wasn't quite as stupid as this fellow said I was. This carried on until I just bulled my way through Hollywood High School without flunking anything.

Then I got down to Cal Tech and was admitted despite my stupidity. Not only did I pass everything in the freshman year, but I was up near the top of the class. I suddenly realized that I did have a brain. So that went to my head. The first term of my sophomore year I let loose and I really didn't do much studying. We took seven courses, not two or three courses the way you take them at the university today. We had seven courses. I had a warning mark in each one of them on a dreaded pink slip at midterm. A suggestion from the dean that I better come and see him.

So I went in and he said, "What are you going to do about that? "

I said, look, this is what happened to me. Don't worry, I'll make it up." I really worked for the rest of the term and made it up.

Well, I didn't make Tau Beta Pi. which is the honorary engineering fraternity, but when I went to the Colorado School of Mines, my friends in the fraternity felt that I ought to be a Tau Bete member, and they wrote back to Cal Tech to see whether they would object to my being put into Tau Beta at the Colorado School of Mines. Cal Tech looked up the history and found that I was only one spot short of my two roommates who were both Tau Betas. So they let me into Tau Beta at Mines in graduate school.

Swent:

Were you in a fraternity at Cal Tech?

Boyd:

No. I had two roommates. One was Bill Aultman. He was a Tau Beta Pi. He became one of the great hydraulic engineers that were charged with building the aqueduct into Los Angeles. He got into a company that he became president of, and later chairman. They set up waterworks supply and sewage all ever the world.

The other one was much quieter. I remember writing to him once and he said he was working for one of the engineering firms. I asked him what he was doing and he said he was drawing plan views of a rivet. He was a graduate Tau Beta Pi civil engineer from Gal Tech and he was drawing circles. Later on he went to work for the famous brain trust T.R.W.

Swent:

What was his name?

Boyd:

His name is Roland Philleo. Both of them still live in California.

Swent:

You said you lived in a house. Cal Tech didn't have dorms originally.

Boyd:

No. They had some fraternities. We didn't get invited into a fraternity.

Swent:

Their dorms must have been new at the time you were there.

Boyd:

They weren't even there. Well, there was a dormitory there. It was an old military building. I commuted from Hollywood for a while. With the first money I ever earned, I bought a car brand new for $350.

Swent:

What kind of car was it? Do you remember?

Boyd:

It was a Star Durant open touring car, which with all my training as a mechanic I used to take care of myself. I ground the valves and set the bearings and did everything you had to do with it. I got pinched once for going thirty-five miles an hour.

Swent:

The first student houses were built in 1931.

Boyd:

That's right. I graduated in 1927. There weren't any houses. We found two rooms connected by a bathroom just off the campus, owned by two old ladies. We rented these two rooms and we put our three beds in one room and our desks in the other room. For three solid years we lived there.

Swent:

Where did you eat?

Boyd:

We would walk up to the corner and get breakfast, and up onto Colorado Boulevard to get dinner. We used to be able to get a steak dinner for fifty cents. My father gave me $50 a month. I earned what, $300 a summer? Every summer we had to go to school for six weeks. The first summer we did mechanical drawing and accounting. The second summer we went to shops, and the third summer we went to military camp. Se I only had about five or six weeks in the summer to earn enough money other than that $50 a month to go through Cal Tech. Today, it would cost $8,000-$9,000 a year to do that. It's amazing. Is this ten-fold increase a measure of the rate of inflation in sixty years?

Swent:

Of course, fifty dollars meant a lot more then than it does now.

Boyd:

Yes. but I did not realize that inflation had amounted to ten-fold in sixty years. I help a lot of people through school now. particularly at the Colorado School of Mines. Two or three of them every year get about $1,000 a year out of it. Even at Mines, which is a state school, it still costs them $5.000 to $6.000 a year to go to school.

Swent:

But you could do it on $50 a month?

Boyd:

Well, nine months is less than $1,000. That was my room and board, running an automobile, and books, and entertainment. And I had a beautiful blonde I used to go with in these days. Her father was a scion of the Ginn Publishing Company. They made the school books, remember? I think they're still in existence. She was a beautiful, wily one. She married a millionaire later on.

Swent:

So you started out as an electrical engineer?

Boyd:

Yes. Then I changed to civil engineering in my sophomore [year]. It didn't make much difference. We all had about the same course for the first two or three years. Because my two roommates were civil engineers I thought that would be a good idea. Then I took one of my classmates up to Ryan with me one summer to get him a job in the plant. He was a mechanical engineer.

We decided together that I would go into mechanical engineering and take economics, and that he would design airplanes. Later on he became a designing engineer for North American Aviation and he helped design the present wing which is utilized by most airplanes today for transport planes. He retired in his fifties. He was a Christian Scientist and became a reader in the church.

Swent:

What was his name?

Boyd:

Frederick G. Thearle. I got him a job up there in the power plant. The power plant was run by hot head engines that go "Put, put, put, put," all night long. But if it ever stopped putting I'd be up immediately and I would get down and help there, get that engine started again.

Swent:

Did the fact that he was a Christian Scientist help your friendship?

Boyd:

I don't think so. Bill Aultman was also a Christian Scientist, and his sister was a practitioner and a teacher. I later went and took my classwork with her. But Rollie [Philleo] was very acceptable it never made any difference to me that he wasn't a Christian Scientist.

Swent:

Did you go through a period when your studies with engineering science conflicted at all with your religion?

Boyd:

No. It never gave me a problem. In the first place. Mrs. Eddy [the founder of Christian Science] made it very clear that science is a science of mind. What we term material science comes only in the mind. Then you translate it into physical things. I never had any difficulty with it.

Swent:

Did any of your teachers ever wrestle with it at all?

Boyd:

No.

Swent:

They didn't try to shake you up?

Boyd:

No one ever tried to change me. They would have had a rough time if they had. No, I never had anyone try to talk me out of it. Not even my wives, neither of which have been Christian Scientists.

Swent:

I think of that period in the early 1920s as being a time when this was a very volatile issue, wasn't it, for many people?

Boyd:

It wasn't with me. As soon as we get to Hollywood we were entered in a Sunday school. We went every Sunday religiously, all four of us. Then as soon as I became twenty I was by this time at Cal Tech I joined the mother church and the local churches, and started teaching Sunday school. I taught there until I graduated.

Swent:

In Pasadena?

Boyd:

No. that was in Hollywood. I always went home on the weekends. The first Sunday school I had to teach was girls who were just about my age. I thought that was wonderful. They would give me these young movie stars who were hard for women to handle. Somehow a young man could handle them pretty well. Some of them were quite famous. They were child actors. I haven't thought about them for years.

Swent:

So that wasn't an unpleasant chore at all?

Boyd:

No, I never had any trouble with that. Of course, it meant that I had to study my weekly metaphysical lesson pretty carefully because I had to question them and do what you do in there. This is what guides us [points to two books] so we're all thinking together at that particular time.

Swent:

The two books, the Bible, and Mary Baker Eddy's Science and Health.

Boyd:

Yes. We always refer to these as our only preachers. We do have lecturers, and we had a wonderful lecturer here this last Sunday, a lovely black lady. She was just as sweet as she could be. Clemmie just fell in love with her. She gave me some great hints about this. That was one of the better things that Clemmie's ever best that had happened to her. She was raised with doctors all her life. It's going to be very difficult for her to say give up doctors completely and depend entirely on Christian Science.

Swent:

Your first wife was a doctor's daughter.

Boyd:

Doctor's daughter. She thought that we were opposed to doctors, but we're not opposing them. We have a great respect for doctors doing what they do for people. That they don't do it our way is not our problem. My father-in-law and I were very close friends. I worshipped the ground he walked on, and he never tried to and Ruthie never tried to she was even more restrained than Clemmie is about taking medicine and things like that. She never expected me to do all that.

Swent:

It's interesting, though, that your friends in college were also Christian Scientists.

Boyd:

Well, one of them, so half of them were.

Swent:

He had a similar viewpoint then.

Boyd:

Yes.

Swent:

There were lets of very famous people at Cal Tech at that time. Had Richard Chace Tolman come yet?

Boyd:

Tolman was there.

Swent:

And Robert Andrews Millikan?

Boyd:

Millikan of course was the top man. He wasn't ever president. He wouldn't be called president, but he was the chairman of the board or something like that. He still taught physics.

Swent:

Harry Bateman?

Boyd:

Bateman was there.

Swent:

Were you aware that these were great men, or were they great at that time?

Boyd:

They were all great to us. I don't remember being highly impressed because few of them were very impressive when you see them that way. I've never been impressed by people. I don't know why. When we get along a little farther we will talk about the people I had to work with when I went to Washington, and particularly when I went to Europe. Then when I came back as director of the Bureau of Mines. I mean. I dealt with some of the great men of the day.

Swent:

I was going to say, you've been surrounded by impressive people, your entire life.

Boyd:

Yes, but they never impressed me.

Swent:

You were born into a whole family of great achievers. Maybe that's why.

Boyd:

I suppose I was impressed, because in writing home I would talk about people I met and worked with and so forth, I was a name dropper, I guess. You asked me to be a name dropper and I'll be doing that, because I'm proud of the fact that I've when we get down to [General] Lucius Clay, for example, I lived with him night and day for four years. Then he went to Germany.

Swent:

But you must have been aware that these professors, for example, were achieving remarkable things, weren't they?

Boyd:

No, I don't think so. Well, Millikan you would be because he was by this time a Nobel Prize winner.

Swent:

Did you meet Einstein at all?

Boyd:

No. I saw Einstein, but he came after I left. In fact, I was going over to Cal Tech one day when he was there and Mother said, "Wouldn't it be wonderful if we'd see Einstein?"

We pulled up in front of it, and who walked across the street in front of us but Einstein. I've heard lets of wonderful stories about him, and of course I knew he was of great mental capacity. But the difficulty of Tech, even today, the faculty are all so highly respected in their fields that you're used to it.

Swent:

It's just the norm.

Boyd:

Yes.

Swent:

And the students, of course, were all of that capacity also?

Boyd:

That's right. I suppose that makes me that way, because after all, when they came to get me in the Tau Beta Pi at the Colorado School of Mines, they went back and found out I had only barely missed becoming Tau Beta Pi and I had no idea I was anywhere near that level. I just thought I was still one of the stupid people. All I knew was I had enough points to graduate.

Swent:

Did your managerial talents show themselves at all at an early age?

Boyd:

Yes, I think so. because I can remember thinking that I would like to be a president of a copper mining company. I can remember it new. I never realized how I would get there or whether I was trained to be there. Why would I go after it? It came to me. I didn't go to it. And I was a crew chief within a year from graduation.

Swent:

But this was something you had thought of?

Boyd:

That's right, because then, when I talked to my friend, Fred Thearle, we decided that he would go on doing the designing of airplanes and I would become a businessman and I would learn to fly. The reason that we didn't go on with that is that my mother didn't like this idea of my going to learn to fly because in those days of the people who entered these flying schools, less than half of them came out alive, something like that. If they didn't come out alive they were washed out because they couldn't fly well.

So I got admitted to this Army Air Force flying school in Texas. If I was going to do what we had planned to do, he would design airplanes and I would fly them, and we would get into the business of building airplanes, this was just a matter of course. I had a course in engineering and economics, mechanical engineering, and he was a mechanical engineer. He was a Tau Beta Pi, too.

Swent:

Was this after graduating?

Boyd:

This was on graduating. Of course, I passed the physicals all right. I could see straight, and my Cal Tech degree seemed to be enough; they didn't need to test me on that one. So I was admitted. My mother fell to work on this fast. She didn't like this idea at all. so she went and worked on their friends in the mining industry, and I get a wonderful job offer to go to the Radiore Company, which was in the beginning of the use of geophysics in mining exploration. They talked me into giving up this flying school and going out taking a job in geophysics.

Swent:

Who talked to you?

Boyd:

My mother, my father, and the vice president of the company.

Swent:

On what basis did he influence you?

Boyd:

Well, they showed what job I could do. and what I would get paid and so forth. Don't forget. Dad never had a very big salary. I don't think his salary was ever over $7.000 or $8.000 a year. He had three more children to educate, so I was on my own. They offered me $200 a month. That was a lot of money in these days.

Swent:

At that point were you thinking of getting married?

Boyd:

We weren't thinking about getting married.

Swent:

But you still needed the money for yourself.

Boyd:

Yes. And I saved up most of this money and put it in stock in the company. Out in the field we were fed in the field and transported. I didn't need many clothes. I worked in the field in just one suit. We didn't drink much, so [laughs]

Swent:

Where did you go with Radiore then?

Boyd:

The Radiore Company was a subsidiary of the Southwest Engineering Company.

Swent:

And they were headquartered in?

Boyd:

In Los Angeles. The man I knew was of Swedish origin. Henning Olund. His wife was a real Swede and a great friend of my mother's. She was a Christian Scientist, too. I don't think Henning ever became a Christian Scientist. I traveled with him a lot later en.

This was Dad's industry. I had been up in the mining industry all my life, or associated with it, and my mother worked pretty hard on me not to go flying. As a matter of fact, the class that went down there, I don't think more than twenty percent of them survived the course. They either got kicked out or they were killed. What would I have been doing? I would have been flying airplanes from there on. I don't know.

[Date of Interview: October 18, 1986]

Swent:

I would like t know a little more about what you think Cal Tech's philosophy or approach to education was at that time? Now that you've had experience with other institutions, what was distinctive about Cal Tech?

Boyd:

I think the most distinctive thing about Cal Tech was the realization that you had to train somebody not just to be a scientist, or an engineer, but to be also a citizen, The breadth of the courses was such that we had, besides mathematics, chemistry, and physics, we were required to take the basic courses in literature and English. In current events we even used what is the weekly magazine Time. Time magazine was relatively new, and was our textbook in current events. It wasn't long before I gave that up because I never enjoyed the fact that they editorialized the news. I haven't really studied Time since that time. But at least in those days we were required to be well aware of what was going on in the world.

Swent:

And that was rather different for a technical school?

Boyd:

Yes, as far as I knew. I didn't know any other schools, of course, but as I went on later to the Colorado School of Mines, we had much greater difficulty getting those kinds of courses into the curriculum, and they had them well established at Cal Tech. For instance, we took from seven t nine courses a term. We had three terms in the year, and besides our chemistry, our physics, and our laboratory courses, we had to have these what do you call them?

Swent:

Humanities.

Boyd:

Humanities. The humanities courses went along with it.

Swent:

There were three terms and then your field work in the summer?

Boyd:

There were three terms a year. Then we had the long summer period in which, at the end of our freshman year we took shop. We had to do machine work or lathe work, and carpentry, and pattern making, and things like that.

Swent:

And that was on the campus?

Boyd:

No, it was in one of the high schools. We didn't have the shops on the campus, but we were sent off there in the summertime. In the end of the second year we came back and we did mechanical drawing, engineering drawing and accounting.

Boyd:

At the end of the junior year we went off to military camp because I had agreed to sign up for ROTC even though at that point I was not a citizen. Until my father became a citizen they couldn't pay me the $75 a month, or whatever it was. But I nevertheless took it because my father felt that I should be prepared to defend the country that I lived in.

Swent:

It's interesting that his terrible war experience at Gallipoli had net turned him against military service in any way.

Boyd:

That's right.

Swent:

And you were still enthusiastic about joining the army.

Boyd:

Well, he had a big influence on me.

Swent:

Was ROTC a big thing at Cal Tech?

Boyd:

In those days ROTC was a big thing. Not everybody, of course, took - it. You weren't required to take ROTC. Until Dad became a citizen they couldn't pay me. I just enrolled. When he became a citizen before I was twenty-one, then I became automatically a citizen and they were able to pay me.

Swent:

And were most of your friends also in ROTC?

Boyd:

No. Bill Aultman wasn't there. I don't remember if Philleo was or not. I don't remember what proportion of the student body, but it must have been about a third of the student body which was in the ROTC. Then they graduated as second lieutenants in the Corps of Engineers.

When we had the final parade in which we were given our commissions, I was asked to be the adjutant and read the orders of the day. That was the first time I realized that I had a bellowing voice that could be heard all over the football field. And I guess that's still true. Maybe people don't understand what I say, but they can't ever say they didn't hear.

Swent:

Did you rise in the ROTC? Was this choice as adjutant because of your administrative experience?

Boyd:

Well, I graduated as a second lieutenant, and I had been a platoon commander while I was there, so

Swent:

So you had already come up?

Boyd:

Yes, up there. Did I mention yesterday that I kept my military training up?

Swent:

Yes, you did.

Boyd:

When the war came along I was a senior captain and was called in as a captain and I went to Washington.

Swent:

This meant that you had gene to camp every year?

Boyd:

I had gene to camp two or three times at the military camp in Colorado, Fort Lagan. I had been to a military camp at Fort Lewis, Washington in my junior year.

I did a let of paperwork. There were courses sent to you for you to study and write reports on. In fact. I sort of became the professor of military history. I had to knew more about the Civil War and what's going on, and what the effects on the organization were during the Civil War. I've forgotten all about it now. but I used to correct the papers of those who took that course. That's the kind of thing that kept me in touch.

Swent:

How did you happen to be chosen to correct those papers?

Boyd:

I haven't the faintest idea. I was just assigned the responsibility. I guess.

Swent:

You must have had some talent that caught somebody's eye.

Boyd:

I suppose so. Or they couldn't get anybody else to do it.

Swent:

What was your motivation for staying active in keeping this up?

Boyd:

Well, I think my father made it clear to me that it was my duty to serve my country.

Swent:

You could have just stopped after graduation.

Boyd:

I could have done, yes. But I never did that. I always kept up with what I did, I suppose. That's the reason. It was a good thing I did, so when I got to Washington they could give me a job on the staff.

Swent:

What other extra-curricular activities did you have at Cal Tech?

Boyd:

Well, I took part in the drama club, and we put on plays. There is a theater in Pasadena, the Pasadena Playhouse, in which a great many movie stars were trained before the days of the talking pictures. I would go over there occasionally and take small parts in that. Gilmore Brown, who was the director at the Pasadena Playhouse at that time was also our coach in the plays, in the drama club.

Also, I swam. My father had thrown me in the Pacific Ocean when I was three years old and said. "You'd better swim; there are sharks in there." That's what he told me. I don't remember that story. But I've swum all my life, and I competed in school in England. Therefore I was on the swimming team and ended up by being the manager of the swimming team in my senior year. The yearbook says that I was the support of the swimming team. I guess I swam about as many races as I could take. But I wasn't very good.

Swent:

Really?

Boyd:

No. Just good enough to win a few medals.

Swent:

And I think you still love to swim?

Boyd:

Oh yes. I've swum ever since. I still swim. But I never was coached. We never had a coach at Cal Tech. We went and swam on our own up at the junior high school pool and at the YMCA, but we didn't have a pool in those days. Now Cal Tech, with some of my money, has got a good swimming pool. Their team is better. But my last year we beat UCLA, so we weren't too bad.

Swent:

Did you have contact with your professors outside of your classes?

Boyd:

Oh yes. One thing about Cal Tech and this is very important your professors were always available to you to help with personal problems. Professor Graham Allan Laing was my professor of economics and business administration. We never called him anything but "Professor Laing." We weren't on a first-name basis in those days. He regularly every term would have meetings at his house where his wife put out the cookies and we would sit and discuss economic questions.

Dr. Millikan had us in to tea or cookies, or whatever it may be, at least once a year.

Swent:

And these are the two fields that you were most interested in?

Boyd:

Well, Dr. Millikan was the head of the school.

Swent:

Economics and mechanical engineering.

Boyd:

Mechanical engineering, yes.

Swent:

Physics was not your major.

Boyd:

Oh no. Heavens, I had a hard time getting through physics.

Swent:

But geophysics became

Boyd:

Geophysics came to Cal Tech after I had left. I had no training in geophysics except in geology. We were talking about the Cal Tech professor who became the head of the California Division of Mines and Geology, Ian Campbell. He was my professor. I got to know him quite well, but the head of the department was then John Buwalda.

I've get a gold-headed prospector's pick up there on the wall behind the gold pan. On my fiftieth anniversary of graduating from Cal Tech I was apparently the oldest living geologist as a graduate of Cal Tech, although I didn't graduate in geology at Cal Tech. I had become a geologist in the meantime, and they always made a fuss of me when I went there. I've get great friends in the department still.

Swent:

You should say that you were given the distinguished alumnus award from Cal Tech.

Boyd:

Yes, but because of my economics, my business, not necessarily because of my engineering contributions, although I guess I've made some or I wouldn't have been elected to the Academy of Engineering.

Swent:

You've always had a broader outlook than just the science and engineering.

Boyd:

That's right. Cal Tech very carefully trained us in breadth, not being tied down to a particular field. While we had to pick a discipline like mechanical engineering or civil engineering, we were expected to broaden our whole outlook.

The professors have always been well chosen at Cal Tech. They're proud of the fact that the Academy of Sciences and the Academy of Engineering have a large component of Cal Tech professors, either before they came to Cal Tech, or while they were there they earned these honors.

Swent:

And these have frequently been men of multi-disciplinary talents.

Boyd:

Yes, I think that's true because without that they wouldn't get appointed. Linus Pauling is an example. His son-in-law, now provost at Cal Tech, was a member, then head of the geology department, Barclay Kamb. He with Leon Silver and Robert Sharp have been good friends for years.

Arnold Bechman was my instructor in chemistry. So I was one of his first students. Few men have matched his eminence in science. industry and support of the scientific institutions. I am sure that I was influenced by his example and enjoy seeing him when we meet on the campus or at meetings of the Cal Tech Associates.

One of my roommates. Roland A. Philleo, designed the civil engineering functions for the construction of the Palomar telescope in southern California. He took me into the laboratory. I saw them polishing that mirror that time. But I had nothing to do with it.

Swent:

And your interest in aeronautics has not continued, has it?

Boyd:

No. I haven't had any great interest in it. Although my fourth son Hudson was a flier and chairman of the Point Lobes chapter of the American Institute of Aeronautic and Astrophysical Engineers. I've had a lot of friends who have been involved in it in the manufacturing end. the research end. but I've never had any particular connection with it, except to fly in my work.

Swent:

You've certainly done a lot of flying, yes. I just made a note of some of the Cal Tech people. Did you have Theodore von Kantian? Did you study anything from him?

Boyd:

No. I was aware he was there, but I didn't have anything to do with him.

Swent:

Tolman. you said, taught one of your classes, physical chemistry?

Boyd: Physical chemistry, yes. I got my physical chemistry from him.

Swent:

Was there any professor that particularly influenced you? Professor Laing perhaps?

Boyd:

Well, Laing, of course, had the greatest influence on me, and Millikan gave me my basic physics. I had to take hydraulics, and the professor who wrote the book from which we worked, we had to check him on the answers in the back of his book. We found some errors in his book. But he was a very prominent hydraulic engineer in the engineering societies, and he would be gone a large part of the time, so we were lectured to by fellows.

The professor of aeronautics I did take aeronautics I will always remember him. I can see his face and I'll recall his name. One day he produced the formula for the air foil in the wing of an airplane. It went clear across the board and then he wrote the answer at the bottom. He turned around. My eyes were wide open. He said, "Didn't you follow me? I just changed to polar coordinates and integrated." It would have taken us all day to change to polar coordinates and another day to integrate it. but he had done it in his head right there. I didn't do very well keeping up with that kind of mathematics.

Swent:

Did they have a let of laboratory facilities?

Boyd:

Oh yes. One of my professors who was quite famous in his field was Royal Sorensen. He was the head of the electrical engineering department. He came from Golden, Colorado, where I was to go later. His daughter was a beautiful redhead, and she was the belle of the campus. She married a man who was a senior when I was a freshman. Peterson. He's done well in the state of California since then, in the electrical end. But I always looked up to him as being my here. In these days, the seniors were that hat that the rangers wear, the flat, hard hat. So I wore mine when I was doing field work for a long time until it wore out. When you get to be a senior you get to wear the hat.

In these days we used to wear plus fours [knee-length pants]. I have pictures of me in these days showing me in plus fours. Then, you knew, we used to have quite a little rowdiness at the universities. One of the worst things was they would get us all lined up as freshmen to get a picture taken, and the sophomores would be up on that balcony above and then dump water on us until somebody let a barrel of water slip out of his hand and almost dumped it on somebody's head. That put an end to it.

Swent:

Cal Tech has always been committed to being a small institution.

Boyd:

That's right. It isn't much bigger now than it was then.

Swent:

This meant a greater closeness to your professors.

Boyd:

You knew your professors pretty well. They mixed. We went to their houses, and they were always open for us to go to.

One of the great things about Cal Tech was, I think, the honor system. When we went in to take an examination we could take all the books we wanted to in there. The only thing you didn't do was ask your neighbor. You swore to the honor system and you didn't crib er you didn't do anything like that. In fact, you could take your examination home and work at home, and bring it back before the hour was over. I did that once. I don't know why. Of course, I almost flunked. We used to leave slide rules and books on the steps while we went to another class. We were very careful about that, and we guarded the honor system pretty thoroughly.

Of course, we were allowed slide rule error. You always carried a slide rule. Today. Koeffel and Esser [manufacturers of slide rules] even turned ever the machines that make the slide rules to the Smithsonian Institute. The electronic calculator and computer have replaced it totally.

Boyd:

The next period is when I turned down the air force. They can never understand why I turned them down. It was because I get a job with the Radiore Company, and we went immediately in the field. I was trained in the deserts of California and then moved to eastern Canada to work under an older man who couldn't stand the cold. When the winter came in the backwoods of Canada he had ta go home. I suddenly became, at the tender advanced age of one year beyond college, a crew chief.

Swent:

Where precisely was this?

Boyd:

This was up in northern Quebec in eastern Canada. We were doing electromagnetic prospecting.

Swent:

Which was brand new at that time?

Boyd: